An Old Man and His Memories - Combined

Looking Back at a Long Queer Life

Part 1 - In the Lobby of the Hawthorne

I sat in one of the big chairs at the far end of the lobby of the Hawthorne Apartments, my home for almost 30 years now, in the Central West End of St. Louis. Not a comfortable chair – straight back, sturdy seat, ornate carved wood arms – but comfortable enough for me to doze from time-to-time as I sat, taking in the mundane comings and goings through the lobby and the revolving brass door.

The April breezes gently lifted the long white sheers at the open French windows into the room, dusty banners of virginity in this bastion of mostly spinster females of a certain age and class. Clem and Our Cellist and I had been among the few males in residence, but males of no threat to the dusty virginity of our lady neighbors.

Outside the windows, flowering plums bloomed in all their pink glory, the petals dancing and swirling on the breezes, and then settling to the ground as pink carpets. Just as I remembered them all those years ago in the Square Paul Langevin (as now called; then, Square Monge) in Paris, as I did vigil across from the hotel I’d been summoned to by Clem, after his long abandonment, when he’d gone back to his “normal” life of family and career in Chicago. That day 50 years before, I’d sat so long, watching as Clem (or someone; it could have been him) opened the balcony window of a room (it could have been his room) to let in the sweet spring air, and, perhaps, to glance out wondering if I would come. I’d sat there so long that the pink petals covered my shoulders and trouser legs along with the bench and path. I’d sat wondering if I would, or could, summon the strength to go in to greet him and pass pleasantries and reminiscences about “wild and foolish” days now past, days before Clem had gone away, before I’d first heard My Cellist play, before I’d cried all the lonely tears that flooded me forward into the life without him.

That day, I had wiped away the tears (after a while); and stood and brushed away the petals; and I had not gone in. This day, as I watched a few of the petals drift in around the sheers, I felt a tear again, at remembrance of things past, and I did not wipe it away until it had gone halfway down my cheek. Old men may cry fewer tears than youths, I thought, but they can be as warm.

That day, I had stood and walked out of the Square, into the rue des Écoles, away from Clem, as he had gone away from me the day I saw him off at Gare d’Austerlitz, leaving me downcast that I was to be alone in Paris for days, perhaps weeks, until he returned from Toulouse and the meeting with his father. His letter, when it arrived, telling me he would not return, left me overcome with sorrow.

This day, I stood and walked across the Hawthorne lobby, greeting the doorman, Jimmy, as I reached the door, then going out into the gorgeous day, a West Pine flâneur suddenly overcome by a feeling of bliss, even though over 70, even though strolling only to the Sam Wah Chinese Laundry on Laclede to fetch my shirts which they had been washing, ironing, folding for me (and so many others) for so many decades.

Ahead I saw two boys walking up the street holding hands. It continually amazed (and exhilarated) me how bold and open the young gays were these days. As though they had no fears or shame about their queerness. We’d had our places of openness, of course – every queer generation has, going all the way back to the climb out of the sea. But seldom, or maybe never before, openly on the street, in the full daylight. Thrilling proof that sometimes there is something new under the sun.

Seeing them brought to mind lines I’d read recently, by the English poet, Philip Larkin – not bad, though no Tom Elliot, certainly, our St. Louis boy who chose England so long ago:

“… I know this is paradise

Everyone old has dreamed of all their lives –

… everyone young going down the long slide

To happiness, endlessly …”

The desire each of these boys had for the other, physical desire, not only the more chastely laudable spiritual kind, trailed behind them like a comet’s tail. I picked up my pace a bit – not too much, at my age, but a bit – so that the dust from it might settle on me before it drifted away in the air. It was that desire I missed most now that I’d become the old man remembering the young man and his desire-bathed life then – that other person and life I used to inhabit in youth – the desired and the desiring in one. Though in some ways the absence of desire made life easier to live.

My feet knew the way to the laundry so well that my mind could stay completely in that day, 50 years in the past, when I walked away from Clem forever – so I thought: what improbable twists life brings!

I’d come back to St. Louis in the cold early months of 1943, at Clem’s invitation, thrown in at the end of a letter about other things, perhaps with no thought that I might actually accept. But I did. The War had hollowed out my Houston circle, and thus my Houston life – Russell gone, Lorin gone, Gene, Cardy, Forrest, and at last even Margo, gone – so why should I stay, the last of our outré tribe remaining? Yes, Houston was a city of the future, St. Louis one of the past, but not many were farsighted enough (not I, certainly) to see that then. And what difference did past city or future city make to one floundering (I, certainly) in an uncertain present? Not that certainty, past, present or future, is ever more than an illusion. Still, even the illusion of it had flown away for me by then, and so I opted for the geographic cure, and flew away myself, to St. Louis. Or rather, took the train, since few flew then.

After so many years of mild winters on the Gulf, a sudden re-immersion in the blast-of-cold winter wallop in even barely northern St. Louis, sobered me out of illusions of a paradise in my new old city. I had forgotten how cold the place could be when someone (God?) left the door to the Arctic ajar, with only prairies between the two points, of no use in breaking the frigid winds. Even though Clem’s hearty greeting when I stepped off the train made the air seem almost warm (that of Our Cellist, not so much), the cold of the train shed tempted me to go directly to the window for a ticket south.

I did not, could not as Clem (Our Cellist, not so much) rushed me and my luggage into a taxi and told the driver to take us to The Hawthorne, as though everyone knew The Hawthorne, of course. This driver, if not everyone, did know. And almost before we’d had time to wonder to each other at the fact of my being there, and wonder each silently what the future would hold for the three of us together, we got out on West Pine, stood for a moment in the cold before the grand revolving door as Clem paid the driver, and then each of us took a suitcase and stepped lively up the five steps and into the warm lobby and greeted the smiling Jimmy, as I had done again today, and for 30 years – the Jimmy then so young; now, like me, so growing old. The first day of the rest of my life, as the young were now so fond of saying.

This warm pink lovely day I watched the boys as they turned left at Newstead, going, perhaps, for a look at the glorious mosaics inside the magnificent Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis, on Lindell. Or (and this, perhaps, as much an old man’s dream as a reality) to a small apartment somewhere near, large enough no matter how small for their desires to flower as beautifully as the spring trees.

I turned right, the direction of Sam Wah, but I glanced back over my shoulder at the boys, just as I glanced back over the years at the boys we had been, Clem, Our Cellist, I – and many others – in the days of our own small apartments filled with our own flowering desires. And even the memories of disappointments so often coupled with the desires could not blunt my bliss (tinged with melancholy as it might be) on a day as beautiful as this. How fine, I thought, to be walking, in my golden age, on pink carpets through air scented with desire, even though someone else’s. A paradise the old – AND young – have dreamed of all our lives.

Part 2 - I Caught Him Reading

As I stood at the counter of Sam Wah – among the last remaining of the once plentiful Chinese hand laundries that had dominated the laundry business in St. Louis – my eyes followed the green tendrils that meandered around the ceiling and windows. We called it an “ivy” when we mentioned it in amazement, though likely it wasn’t botanically an ivy at all, but something else that could thrive, or at least survive, on years – maybe decades – of inattention and little water, verging almost on abuse. Much as Sam Wah, and the other St. Louis Chinese had survived over the decades, perhaps.

There was a move afoot to save Sam Wah from destruction as the ever-expanding institutional behemoth of the neighborhood, the Washington U Medical Center, hulked its way further east. I supported the effort to save it: I could not imagine entrusting my shirts to anyone else, after so long; but I left the protesting and petitioning to others. As I grew older, and my time grew shorter, I left more and more to others. An old man does not have time, or energy, for all things, even all good things – must choose the few most important things (important for him, at least) to give himself to. Even though knowing for sure which are “most important” might often be difficult.

My eyes followed the vine back to its encrusted pot on the window ledge as I waited. In a few moments, one of the Gee brothers, who now operated the laundry – they alternated between manning the counter and supervising operations further back (laundering, ironing, folding, bundling) – handed me my parcel of shirts, tied in brown paper with twine. I paid – cash, no check/no charge. We nodded, as we had done a thousand times before.

As I walked back out onto the sunny street, I wondered if the vine might prove to be the lucky mole hair for the longevity of Sam Wah. I hoped so. I’d seen quite enough of change to make me right and truly sick of it, when it came to the foundation elements of my world.

I walked west on Laclede, the two blocks to Euclid, and went into the not quite greasy spoon on the corner, Habs House. I greeted the owner at the counter, and nodded to his wife at the grill, doing the short-order cooking. We knew each other for pleasantries, but not by names.

I bought a coffee, not so much because I wanted coffee, but as a reason for being there, to see if the young man I’d seen there so often before was there again. And he was, sitting at his usual table by the window on Euclid, the remnants of his two-eggs-up-with-toast pushed aside, his own paper cup of coffee before him, his eyes seeing only the pages of the paperback book he read. Faulkner today, as it had been for a while now. Before that, Dostoevsky. I’d even watched him reading Proust at times (the Scott-Moncrieff translation), scribbling words on a pad – perhaps the many that would be unfamiliar to a young reader, to be looked up later – as I had done myself once upon a remembered time, long ago.

I thought of him as “boy,” that nostalgic term for young men so much younger than an old man like me, though he must certainly have been well into his 20s. I’d never spoken to him, though once or twice we’d smiled. I suspected him of being an aspiring writer, as I had been myself – long ago. So long ago that it seemed as though I must be remembering some other person. Could that really have been me?

I looked at him, not with an old-man’s lascivious eye – though I can’t deny at least a tatter of desire (so not quite dead yet) – but perhaps with a little envy that he still had so much ahead of him that I now could only dimly see in my past. It would not all be easy or pleasant, likely much would be painful, but all part of a life yet to be lived, instead of one now mostly to be remembered.

This was not to be another day of smiles exchanged for us. Faulkner proved too absorbing a rival. And so after I’d watched him read for a while – discretely enough, I hoped, so as not to be found out by our Habs House hosts – I got up to leave, getting almost to the door before I realized I’d left my parcel of shirts on the table. As I went back to get it, I blushed a pink only a little paler than the petals falling from the spring trees outside. I glanced at him and at the owners. If he glanced back, I missed it.

I glanced at him again, through the window, as I walked up Euclid. This time he did glance back, though his glance may have missed seeing me as it focused on distant Yoknapatawpha instead. I understood. I soon glanced myself into the distance, to the past. And so we became fellow travelers to other times and other places, joined in a flight from this world that we shared, into others that we didn’t.

When I’d first joined Clem and Our Cellist in their two-bedroom Hawthorne apartment, I’d had my bedroom and they theirs. After I’d been there for a while (but not too long a while) both bedrooms became “ours.” None of us ever said the words to make it so, but we all came to know, accept, even relish that it was so. Even though I had come into their space, I never felt, nor was made to feel, an interloper. I’d come late to the apartment, but I’d been first in knowing each of them, which soon seemed to make us all equals in our menage – sooner and more smoothly than I might have either hoped or dreamed – if I’d been able even to imagine (dream of) such a menage for us at all before it happened. What I’d first thought might be displeasure from Our Cellist at the arrangement, soon enough became acceptance, may only have been Gallic reserve all along. And Clem, straightforward as always, made his druthers clear early on. After just a little time, I simply shook my head in wonder whenever I thought back about it. Our new connection quickly came to seem the inevitable outcome of all that had led us to it. Always meant to be. Why even question how it came to be. Even our tiny table at Café Gaudeamus in far away Paris would now be large enough for three.

In those days, those early winter days of 1943, we took the first faltering steps toward a life that would see us comfortingly through the next many years. Clem had found a new freedom in St. Louis after so long constrained, in Chicago, and even in far away Paris, by the expectations that came along with “close-knit” family – which is to say, a father, and even a mother and milieu, with expectations of the man he should be, no matter the man he was.

Neither Our Cellist nor I had those external expectations to conquer – his family far away in some rural French village that he had not visited in decades, mine all gone. He seemed to have found all he needed with his symphony chair and musical life in this outpost of France, where Saint-Louis himself reigned atop the highest hill in Forest Park. All of us sensed the rightness of our coming together at last after so long of being only partly the whole we now seemed meant to be.

As I continued up Euclid to West Pine, and turned to take my shirts back to my Hawthorne apartment – now “mine” alone, since I now alone remained to live in it – I thought back over those many years when the apartment had been “ours,” and how we’d enlarged our domestic domain over the decades, as adjacent apartments – first the efficiency next door, and then the one next to that – came empty, and we’d moved into them as well. At last we’d had almost the whole 17th floor, each of us with a door that closed, for when any needed a room of his own, but all having all the keys.

They had not been perfect times, because no times ever are. But they had been “our” times, in a way none of us could have imagined before they came, and which now I missed more deeply than I could ever have imagined. Now that they were gone (the times AND the men), I so often feared I hardly had the courage to endure.

Part 3 - Meeting Tennessee

After decades of nibble nibble nibble, the time-eating monster now seemed to be gulping larger and larger bites of the little time I had left. I tried not to dwell on it, since I could do nothing to change it. Well, not quite nothing, but the something had not yet become an option I chose to take. Though I could imagine a time when I might. Especially now that our menage had been reduced by the life-gobbling monster to me alone. But for now, even just remembering sufficed for getting through the days.

But why be so morbid on such a beautiful day!? Just remembering has its own beauties. And as I turned into West Pine on the way back to my Hawthorne sanctuary (yes, now mine alone – mine and my memories), I thought back to a day in that other April all those years ago, a day not unlike this one, with clear sky and fresh air, with a boyish charm teasing me into feeling almost boyish myself, as I walked up my then new street, the petals, swirling around me in the breeze, even pinker in memory than the ones that swirled around me this day as I walked the same route up my now old street.

This day I greeted now old Doorman Jimmy as I walked through the lobby, as I had greeted Young Jimmy then; I took the same elevator up to the same floor; and opened the same door with the same key into the same apartment.

That day, as I stepped into the entry, I heard an unfamiliar voice, a southern accent almost juicy and swallowed, spoken as though the tongue might almost be too large for the mouth, occasionally cut by a raspy laugh that relieved the tension which seemed to come as a requisite adjunct of the words.

“One must be known in order to be forgotten. I will be known. I assure you of that. The other part will be as it may.”

They both laughed, this unknown person of the voice, and Clem. I stopped for a moment before going on into the main room, wanting to hear more of the voice before it became tethered to a person. I saw them from behind as they spoke, looking toward the windows.

Clem said, “Tell me more about the harrowing encounter with trade you mentioned in your letter.”

“This is the first time that anyone ever knocked me down and so I suppose it ought to be recorded. Why do they strike us? What is our offense?”

The mellifluous voice lingered on “strike” and “offense,” pulling out of the words all the drama they contained.

“It was a case of guilt and shame in which I was relatively the innocent party, since I merely offered entertainment which was accepted with apparent gratitude until the untimely entrance of other parties.”

He closed his eyes and tilted his head back as he continued, going back in memory to a world more real than the room he sat in at the moment.

“We offer them a truth which they cannot bear to confess except in privacy and the dark – a truth which is inherently as bright as the morning sun. He struck because he did what I did and his friends discovered it. The sort of behavior imposed by the conventional falsehoods.”

He opened his eyes and touched his finger to his cheek.

“My face was swollen from the blow – but the donor will remain in my memory always, and as a lover, not antagonist. There was something incredibly tender and sad in the experience. So much of life at its most haunting and inexpressible.”

He looked at Clem directly as he continued, “Not that I like being struck, I hated it, but the keenness of the emotional situation, the material for art – these gave a tone of richness to it which makes the affair unforgettable among many that melt out of sight.”

As I entered the room and Clem saw me, he brightened and gestured in my direction.

“Here he is, the Houston friend I mentioned – the one who knows your Margo Jones.”

The person of the voice looked at me and smiled and nodded.

Clem continued, “ And this is Tennessee – the budding playwright I wrote you about.”

Now I thrill at the recollection of being there on the verge of a career as brilliant as the brightest comet in the night sky. But then he seemed just one more talented aspirant to life in drama – of which there had been so many – including me, for a time – and so many would flame out and fade away quickly, as even the brightest stars grow dim with approaching day. Of course, his star, or comet (or whatever celestial body one might choose to liken such a talent to) would blaze – before even it dulled eventually.

“I have been away from St. Louis so long – in New Orleans and New York, and most recently in Jacksonville, working for the War Department – in a very minor role, but part of the war effort none the less,” he said, as we chatted, the spring sun flooding through our windows.

“Except for these two” – he nodded toward Clem and Our Cellist, absent but implied, away now at a symphony rehearsal – “I have no friends here, see nobody, but every afternoon about five thirty or six I go down on the river-front and have a beer and listen to a juke-box in one of the dusky old bars that face the railroad tracks and the levee. That is the only part of St. Louis which has any charm.”

Clem reminded him that there were a few places not far from the levee at which he might meet St. Louis “friends.”

“And I do have a great deal of tension building up, if you know what I mean, which will demand release at some point. But the local Belles are not to my liking – and I wouldn’t risk trade here where my parents and my grands live. Though, with all the comings and goings of the war, there is such a lot of lovely fresh trade – in uniform – passing through the city – many so naïve, and fearful from the hygiene lectures thrust on them by their officers, that the level of their “tension” almost approaches mine – and makes them so ripe for “release” of a kind the lectures do not include.”

I had not had much exposure to such gay repartee since my time in New York, almost a decade before. It had grown tiresome then, and would likely have soon grown tiresome again – though perhaps not, coming from such an acid witty tongue as his. But soon the conversation shifted to theater, about which this new acquaintance had interesting observations – and to his own plays, about which he had absolute certainty – a certainty of such magnitude as I had not encountered since Margo. They were clearly fated for each other, and I would only be one of the supporting players helping their plot along.

That I had even such a small part to play made me deeply grateful – not for his sake, nor the sake of drama, nor even Margo’s – but selfishly, for my own. His agent in New York, had told him about Margo, the “Texas Tornado,” who might be interested in producing his Battle of Angels – “to shock the South!” In quick succession, he’d met Clem, who had “a Houston literary friend who might actually know the Tornado”; and Clem had written his letter to me, adding at the end his invitation to come to St. Louis; and now I had my new life-of-three – all thanks, in a way, to this “Tennessee” stranger and his plays I’d never known existed.

I wrote Margo right away and assured her, tongue-in-cheek, that she and this young playwright were “destined to make beautiful theatre together.” It proved to be so, whether my intervention played any part or not. But I could never doubt that their drama played an integral part in charting the course of mine.

It seemed to make me almost a person of interest to him, aside from my perhaps useful connection to Margo, that I had known Pavel Tchelitchew in Paris in the 20s, and Charles Henri Ford in New York in the 30s, even before they became the couple that Tennessee himself knew in the 40s. Such a small queer world ours could be, all of us members of a “brotherhood of lovers,” as Whitman wrote, that connected us over geography and time, magically, it seemed, without the ties of blood or tribe or institution. We found each other because finding each other – others like us – had to happen, nature demanded it – and survival, both physical and spiritual. And so we of the brotherhood found each other, wherever and whenever: we had no other option if we were to have lives worth living.

Part 4 - Down Mexico Way

When I got up to the apartment – which I called “the” apartment, since I could no longer call it “our” apartment, and saying only “my” apartment still made me sadder almost than I could bear – once I got there, I unwrapped my bundle of Sam Wah laundered shirts and stacked them precisely with their fellows on the closet shelf. A certain old-maidish obsession with orderliness had crept into my habits now that I no longer had any compromises to make with the ways and wishes of others. Though I really should call it old-manish, I suppose, in these modern times, now referring to the old man I had become. It seemed to give me a bit of comfort in my aloneness when everything in my domain had its place, and was in it.

At the bathroom sink I washed my hands. Fastidiousness as regards handwashing had also overtaken me. And as I dried them on the hand towel, I twisted the ring I always wore, the Mexican silver one with a parrot head, inlaid with mixed metals and stones, designed by Tamayo for Los Castillo, they said at the store in Taxco. Was it the one I’d bought for Clem, or was it the one for Our Cellist? I’d bought the same ring for both of them, and a pin of the same design for myself, so that when I walked between them we all sported the same image, a subtle statement of our connection – for those sharp enough to see the personal meaning beyond the subtlety. I saw it; we three knew; even if no one else did.

I’d got them when I went to visit Gene and his new “partner” in Mexico in ‘48. I’d heard already, through Margo, that Gene and Cardy had reunited after the war, and moved to New York, and then parted ways. Ah, New York: that great crucible for the melting down of relationships! Even the most golden of them. It made me sad for them to think about it. And not just for them.

But tomorrow is another day, even for love, and that day, or one of the ones after, had dawned brighter for Gene by the time he wrote this to Margo, who passed his letter on to me:

Cuernavaca

Nov. 4, 1947.

… Margo, we have a beautiful house here, that we’ve rented for a month, which we want to rent for a year! Eight bedrooms, enormous verandah, gardens, swimming pool, gardener, cook, and for so little $.

We thought it might be fun to keep it – and rent out rooms just to people we know – at cost. It’s in one of the most beautiful parts of Cuernavaca – and god knows beats any hotel.

You must imagine me, here, stark mad, with all of this amazing beauty. Never felt anything like it.

Love again,

Genie

When summer came, and I found myself on my own – with Clem off to a family gathering on Lake Michigan, and Our Cellist at a music festival somewhere in high mountains, I wrote Gene asking if I might still be numbered among those “people we know” of his letter.

His reply came as quickly as the international mail could bring it – and I made my way to Mexico – aboard the "Aguila Azteca" – Aztec Eagle – via San Antonio and Laredo. I might have stopped in Dallas, city of Margo’s new home and theater, had she not already embarked on some frenetic summer theatre tour. Or in Houston, which I had not visited since my move to St. Louis, but Mrs. Cherry had written that she hoped to decamp to a cooler summer clime with her daughter and grandson; and McNeill no longer lived in the city; and almost all the others, my others, had gone away to other lives – all those who had once made Houston a home-place for me, even a queer space in which to live a queer life with other queers – “people like me,” as Forrest had said when he came to Houston in search of those of us like him, who would make at least a small corner of the world a safe place, at least a small part of the time. What point in stopping in a city now hollow for me, without a reason? And so I flew on the Eagle as quick as it would take me, to the Aztec lands.

The Cuernavaca house was enormous, the gardens lush, the cook an Aztec kitchen magician. I relished the time catching up with Gene – and seeing all his new work, infused with the colors of Mexico. His new partner, Jon, a jewelry dealer hoping to become the merchant prince of the Mexican silver renaissance in the Texas market, had his charms – though nothing near Cardy’s beauty, but beauty isn’t everything, I suppose (sigh).

Their Cuernavaca circle glowed with the same rich sheen as William Spratling’s silver. The circle included Spratling himself, in fact, who took a group of us sailing aboard his yacht out of Acapulco one delightful afternoon – Gene and Jon, of course; Herbert Harmon, jewelry designer, and wife (“Yes, surprisingly he married,” to adapt a friend’s comment about someone else); an American cousin of Winston Churchill; from the movie world, the head of publicity for R.K.O. Mexico; Edna Lewis and her sister Irma, who had organized an art school “down here” – and talked of starting one in Positano, Italy.

The Harmons invited me to stay, should I want a bed in Mexico City.

“The Harmons are all enthusiasm for what I’ve done already,” Gene said. “In fact, they want to give me a show at their place in Mexico City – as they think that what I’m doing will go well there, seem to know lots of the right people in the City.”

I gratefully declined their offer, even though Gene assured me that the Harmons’ penthouse, near Reforma, was "très élégante." Why should I leave the serene beauty of Cuernavaca, even for the metropolitan excitement of Mexico City?

Through the days, Gene shared glowing memories: the promises now fulfilled of our little Houston group from the 1930s; the British Neo-romantic gay artists he’d met in England during the war; how touched he was at Margo’s comment in a recent letter, “I think you know how I feel about your great talent – and how very proud I am of you.”

When he spoke of Cardy, his tone turned a little melancholy, and I sensed that he’d left Cuernavaca and that day, at least his spirit had, for another time and place, now lost, but still a little longed for.

Then, in a moment he returned, and outlined his novel plan for selling “futures” in work he had not yet even begun, to supportive stakeholders who would have first choice of those paintings once painted – a way of raising money for living, and renting the house, in Mexico, that would make the painting possible. I overlooked that our talking seemed so much about him and so little about me. Friendships, almost as much as marriages, survive through compromise, for better or for worse. And I had long ago accepted my spot in the background as the price of friendship with Gene.

Our pleasant Mexico life went on for a few weeks, with delicious lunches in the garden paradise beside the idyllic pool, the glittering company coming and going, “Talking of Michelangelo.” I could almost have longed for it to go on forever. Though even with the novel delights, I also longed for the time when I’d be returning to our menage in St. Louis.

Then one afternoon, Gene threw out in passing that Russell had opened a store in Mexico City, not far from the Harmons, on Florencia Street, selling Mexican items – paper flowers, bark paintings, “native” dresses – for all the American tourists flocking south. The owner of the shop had dropped an “L,” now only Russel, so Gene had not been sure at first that he was the same, our Russell. He’d been to the shop; had chatted with Russel; had admired the beautiful (of course they were) things he stocked.

The thunder-bolt news stunned me. How could no one have mentioned it to me already? Nothing could have shocked me more: Russell here in Mexico, and people who knew us both knowing it, and not knowing to telegraph the news to me instantly!

The Cuernavaca serenity, fickle as a good hair day, gave way in an instant to turmoil and sleepless nights which would not be tamed until I had made the trip – had seen for myself that this Mexico Russel was indeed my Santa Fe and Houston Russell. Suddenly a visit to Mexico City held added interest, seemed more appealing, became imperative. As soon as I could manage it, I went.

Part 5 - Mexico City Encuentro

Once I’d heard from Gene that Russell now lived in Mexico City, I could not rest easy even in the beautiful house in beautiful Cuernavaca. As soon as I gracefully could, I went to find him. I could not attend to anything else until I did.

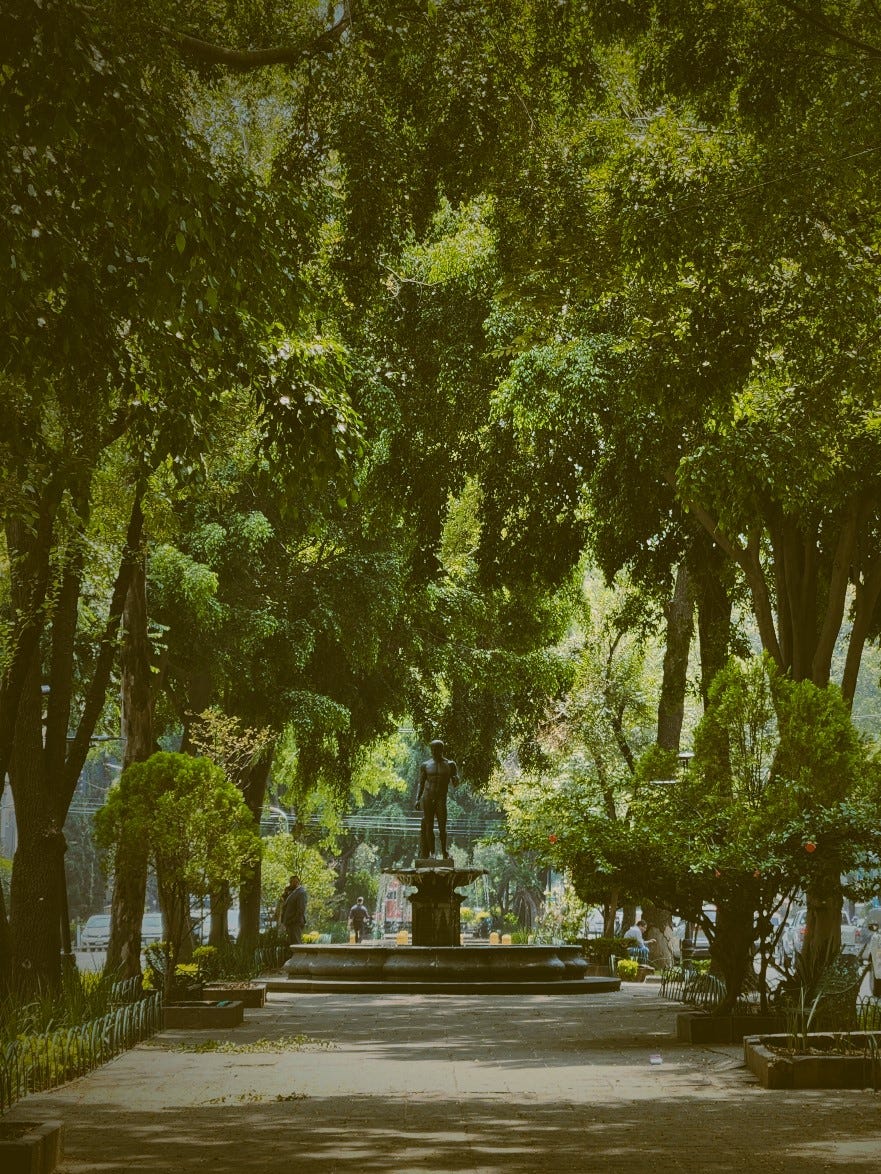

I stayed, not with the Harmons in their swank Reforma penthouse – though he cordially invited me (she, not so much, which forbode a possibly icy reception that I thought it best to avoid). Instead, I found digs more my style in a room of an art-filled house – much of the art Mexican and much of it exquisite – in La Condesa (Hipódromo more precisely) just off Parque Mexico, steps from Avenida Amsterdam, which encircled the park. The back balcony of my room looked onto a patio with walls painted brick red and dusky yellow, setting off the lush green of the tropical plants. From the front, I looked down to the equally lush and green promenade that ran all around the center of Amsterdam, perfect for evening paseos with lovers both current and past. There it was, along Amsterdam, that Russell arranged to have our lovers’ paseo – past lovers, it would be – of recollection, explanation, reconciliation.

I had walked by his shop and looked through the window and seen him there, with a customer, who felt at that moment, no doubt, that she mattered more to him than all else in the world. I remembered that feeling in his presence once upon a time myself. I thought of going in, but I knew that it was neither the time nor place for the meeting I wanted with him. And so I telephoned, and left a message with the shop assistant who answered, asking when we might get together – as old friends bridging the years.

He returned my call in the afternoon and left a message with my hostess, suggesting that we meet at the Foro Lindbergh, in the center of the park, toward sunset, when his shop had closed. Then we could go to dinner and catch up. He’d be wearing a red paper rose (he sold them in his shop) in case I did not remember what he looked like after so many years. (Oh, I remembered; how vividly I remembered!)

At 5, I stopped for churros and chocolate at a little place just outside the park – it seemed the perfect pastime on a perfect summer afternoon in an exotic city, as one anticipated a rendezvous with a former lover after many years. Or should that be encuentro, since we were in Mexico City instead of Paris? I hardly knew what I expected to come from our meeting, or even what I hoped for. After so many years, and with my new-found contentment in St. Louis (or was contentment too saccharine and trite a word?), surely I had no yearning that we might reunite. Even the utterly romantic, once so badly burned by romance before, must be too rational for such thoughts as that. And yet, as my rational fraction asked: Then why else did I even want such a revisit to the past?

And yet and yet and yet. And yet once again that Faulkner truth that the past is never really past as long as those of us who lived it are still alive to remember it, and long, even just a little, to have it back again.

The waiter brought my order – a cup of chocolate thick as Jell-o pudding and a long golden churro encrusted with sugar and cinnamon. Beautiful, with his black hair and dark eyes and flashing smile, he said “buen provecho” as he set the delights on the table before me. And he looked down at me with a lingering glance, a glance I’d seen many times before in many different cities, a glance as universal as music, for those who know how to interpret it.

Or maybe I only saw the glance because I wanted to see it so much, because I’d seen it less and less as the years passed, and something about this charged scenario – soon to be meeting an old lover to ask him directly at last why he had left me, after so many years of wondering – something about this appointment in this exotic city, with so much masculine beauty all around, made me long to think that such a glance could still find me, even now.

It was with such thoughts – and longings – that I passed the long minutes (stretching into hours) until we’d meet in the park. With such thoughts, and with watching, from my sidewalk table, the handsome dark young Mexican men coming and going along the street, at the end of their work days and the beginning of their enviable young nights.

As I sat over my cooling chocolate, growing even thicker as it cooled, and which I didn’t drink, stirring it slowly with a churro, which I didn’t eat, almost forgetting both as my mind traveled over geography and time, I began to wonder (and fear a little) what it would be like seeing Russell again, after so long – almost 10 years. I had changed, both in person and as a person. And, of course, he would have changed too.

The intensity of our short time together – not even two years, from the first chance meeting in Santa Fe to that last night after the opening in Houston – had burned an image of him into my mind – an image which had not changed in the 10 years since. An image that I had treasured, even at the times when I wished I could banish it forever.

Now that the image and the man had an appointment to keep, I almost gasped at the possibility that they would not have anything left in common, after so long apart.

As I sat there, I went so deeply into that other world, memory, that present and past became the same, for a little while at least. I made that reckless error of thinking back to the great loves of my life. Not so many: Clem, Our Cellist, Russell. How lucky I felt myself, that I could think of them as “great,” even though each in turn had brought pain that seemed almost as great as the love. There had also been other, lesser loves and pains, many of them – some that seemed so foolish now that I blushed remembering them – but those three were the great ones.

And now two of those had returned to me, not so much the great “passionate” loves they’d been in their first form, but still great in the sustaining way that makes even passion seem pale. Could it be possible that the same might be the case with Russell? Would I find soon that my third great love could come back to me too, the gold of mature comfort transformed by the refiner’s fire from the silver of youthful passion?

Though, of course, my time with Russell had not been in youth; and who knew if the Russel, with one “L,” I was about to meet might be so changed from the Russell I had known that I would not recognize him – even with the red paper rose?

By the time I’d come back from faraway and long ago, I’d sat at the table with my uneaten chocolate and churro so long that the other tables had all filled, and the waiter looked at me, not with that glance of “perhaps desire” that I’d almost convinced myself I’d seen before, as with that unmistakable look of agitation at a guest who’d overstayed his welcome. I tipped him well to make up for my heedlessness, and as I stood to leave, I smiled, and he smiled, and I thought I saw …

“No fool like an old fool,” I thought as I walked the short distance to the park, and I smiled an amused smile at myself that I could still entertain such young-man fantasies. Would that I could still entertain them even decades hence – and still smile knowing that they were fantasies.

And as I went into the Foro Lindberg, I saw Russel(l) far on the other side – saw first the red paper rose, of course, though even without the rose I thought I’d certainly have recognized him. Even after so many years.

Part 6 - Ah, Russell

I took out my list for the day, and checked off the first item: 1. Fetch shirts.

Next on the list: 2. Pay Bills.

The wisdom of age is valued only by the aged, and even for them (even for us – I admit it, I’m firmly one of “them” now), is seldom of any real utility.

The thought flashed through my mind as I sat down at my desk, in what had been our second bedroom, the one used by the one of us who might, any given night, want to be alone, for whatever reason. The room still had it’s single bed, in the unlikely possibility that I might have an overnight guest. Though that had not happened for so long that it hardly even counted now as a plausible reason to keep it. Who was left now to be that guest? A bed with no head to rest in it. A waste of space, especially when adding bookshelves would have been so much more useful. But there the bed still was – and there had been nights, not so many in more recent years, when I’d chosen to sleep there alone myself, when the loneliness of the larger bed next door became too crushing.

I took my checkbook out of the center drawer, and placed it precisely beside the pile of bills to be paid. I always wrote the checks with the gold fountain pen Clem had given me our first Christmas alone again, since those early days, so many years ago, when we’d first been together alone in Paris.

“For writing our memoirs,” he’d said, as he gave it to me.

We both knew that the memoirs would not be just mine and his, but those of all three. Clem and I still had each other: that was the blessing. A blessing destined not to last, of course. But so much of each of us seemed vacant then, when we no longer had Our Cellist. Why does no one tell the young that even the grandest parts of life – like love – are only temporary? Thank God the young would not believe them, even if someone told.

That evening in Mexico City, Russel and I had gone to our dinner, at a festive little restaurant he knew well, on Av. Nuevo León, where he introduced me to guacamole and chilies en nogada, the snow white sauce, scarlet pomegranate seeds, green poblano stuffed with meat and fruit - the glorious colors of the flag of Mexico. And for dessert, flan – cousin of the French crème caramel I’d been so fond of in Paris.

We’d stayed at table for a couple of hours, chatting cordially enough, remembering our shared days and people and memories past, with the lively music of mariachis doing their best to keep nostalgia from curdling to melancholy.

This Russel of one “L” still had his charms, some of them as captivating as those I so dearly remembered in my Russell of years before. He still had his looks, a little older, a little grayer, but no less alluring, taken in by my older, hungering eyes. He still gave off the air of one who admitted lucky others into his aura, and I felt once again flickers of the thrill of being one of the lucky.And yet, that evening the flickers never flared into flames, and, as the hours passed, I came to know that they never would again. Some loves can go on forever – at least as much of “forever” as humans have. Some can fade and then come back again, different perhaps, but as alive as ever. Some, once faded, are best left memories. My love for Russell – without the second “L,” the lost letter only a symbol, certainly, but perhaps a symbol for something irretrievably gone – would, it seemed, be one of those.

He told me that he’d come to realize that he must leave Houston, the life of hands that could not be held in public, and kisses that could only be exchanged in shadows. He’d watched the anguish that Forrest felt, and could not escape; the Kabuki of deflection that Gene and Cardy performed, even before their friends; heard the little lies that we all told the world – even told each other; seen the snickers as we walked past, even at times from those who should have known better. And it had come to feel like a pillow smothering the breath out of him.

He had not told me he was going because he knew that I would do my best to convince him the little lies, withdrawn hands, gasps for breath, were worth suffering to keep what we’d been able to cobble together between us – even in secret, even in shadows, even in shame – a shame so ingrained and so persistent even I could not deny it. He hadn’t told me, because he’d decided that it would be ultimately less painful for me with a quick, decisive cut, which would heal more quickly – like a kitchen cut from a razor sharp knife, instead of a dull one. And a dull one, he thought, a protracted parting would be bound to be.

So thoughtful of him; I could, of course, only be grateful.

When we parted, with a handshake and not a kiss, I walked back alone to my room overlooking the garden, with only a single glance over my shoulder at his receding form, and I almost wished I’d left him, and our time together, entirely in memory. The memories of “then,” though still sweet, would never again be quite as sweet as they had been before. And I would never again think of him, and of us together, without wondering just a little how I could have been so beguiled. A mystery I had not known before that night; a mystery that had not existed before, because my mind could not conceive it until then.

I still had the portrait he’d done of me all those years ago on our day at Galveston Bay – the one I feared then might reveal “too much.” It had been leaning against the back wall of a closet ever so long. I had not looked at it again since I put it there. I wondered what it might reveal now; if it might offer any clues bearing on this new-found mystery. Perhaps I’d take it out and look again. Perhaps.

I looked out the window, toward the gleaming Arch in the distance, as I made out the checks for the electric bill and the telephone, Straub’s, where I charged my groceries, and, once again this month, Bissinger’s for the chocolates that made any resolutions about losing weight moot as soon as resolved. I’d be going to Bissinger’s on McPherson Avenue again this very afternoon, in fact, and so could deliver that check by hand. Save the stamp.

And perhaps there, amidst the rich walnut boiserie, surrounded by the mahogany desk for writing love notes on enclosure cards, and the display cases filled with glaceed oranges and apricots au chocolat, I might find some morsel to sweeten the bittersweet taste left from those great loves from the past which sometimes proved not to be quite so great.

Part 7 - Poor Sweet Lorin

(Note: Catch up on earlier parts of the story HERE.)

Of course, I could not think of past loves without thinking of Lorin, Sweet Lorin, Poor Sweet Lorin.

I had not been so rash with my memories of Lorin as to test them with a rendezvous, so Lorin remained in my memory as he had been when we parted that last morning when the specter of his father, my own youthful love, had come into bed with us. Once there, the idea of him refused to leave, and so Lorin had left. I understood why he had to, though I’d wished he hadn’t.

News of him had reached me over the years, by way of Margo, the conduit of memories of our Houston group of the 1930s, as she had been the center when those of us who made the group were making the memories themselves.

Of course I’d seen Lorin a few times after he’d left our bed that morning, at gallery openings and parties and that evening of the opening of the Stage Canteen, and the unveiling of his murals there, just before I left Houston for my new life à trois in St. Louis. But I’d seen him from a distance – a distance I’d made no effort to traverse. I’d known that no bridge could span that distance, and I’d been “mature” enough not even to try (or pine) to do so.

And yet, and yet, and yet. Isn’t it really true, secretly true, that we make such “mature” decisions, and yet still keep a tiny flame of hope burning that we might be immature enough to try, and surprise ourselves at the outcome? That, surely, was what had compelled me to that final evening with Russel – and the truth that that final “L” was, indeed, lost forever.

So I relished the news of Lorin in his letters to Margo, which she sent along to me, always with the understanding that I’d read them, perhaps cry a tear over them, and then send them back to her, whether blotted with teardrops or not.

In the first years, the youthful hope:

Los Angeles, November 1947

Dear Jonesie,

First we (Alan Taylor) tried San Francisco, but, while it has a lot of charm, it was so conservative that my “BRILLING PIPE DREAMS” – were completely out of place. S-o-o-o-Down to Los Angeles, where things are shaping up much better, “Ain’t that nice” –

I quit work the first of the year to paint and sculpt – just to find out for my own satisfaction, if I could. Painted at least six hours every day – Amazed myself even. In seven months – Jan-July – I acquired thirty canvases and six pieces of sculpture. More work than I’d turned out in the past ten years. Pretty damned good too. Surprised everyone except me. HAW!

And then the thunderbolt of disillusion:

San Quentin, June 1950

Dear Margo,

Letting you, or for that matter anyone, know where I am – was a very difficult decision to make – and for very obvious reasons! How, where, or even if, to start any attempt to explain my unhappy predicament – escapes me. I do know it is impossible for me to scream – “Bum Beef” – even my elastic conscience won’t permit that. At first, I did think the judgement pretty harsh! After salvaging what integrity I had left – I could reach only one conclusion – I received what I deserved, and – I still don’t like it! One to fourteen years. A pretty severe blow. I can only hope the patient recovers, without scars – at least none that show.

Thinking of you, I naturally think of the “Playhouse” days in Houston – what a wonderful, stimulating, time that was. It’s been fun, keeping track of the successes of the “alumnae” of your Playhouse – and quite successful some of them are, too!

Of course those days are almost painfully nostalgic – also sort of Hysterical – either with happiness – or loaded with “Tragedy” – most of the tragedy, at least for my part, isolated remnants left over from adolescence, which had not been fully exploited, so had to be dragged out and milked of every drop of emotion. Remember how every gesture had to be extravagant, and every sentence ended in an exclamation point!

“… I remember too how every ‘New’ love, and there always seemed to be a New one, was the ‘Great’ one. Of course I saw absolutely no humor on this point at the time. But now! My god! Sometimes I wish I could still feel as intensely. Too old. Too fickle – or perhaps just too jaded? Never matter – I’m happy in my monogamy – just I and me – I think that’s a joke (?). Oh! Well, I never could admit to modesty – not without a twinge of conscience, anyway.”

What offense egregious enough to get him there, and for such a fearsome sentence, I never knew. He never named it in his letters, and, if Margo knew, she never said. Those were perilous days for young gay men in search of “New” loves – whether great or small, long or short – and so I often thought he may have fallen prey looking for love at the wrong place, at the wrong time – wrong as the proper world (the straight world) said at the time. But I never knew.

What I did know was that when they finally unlocked his jail cell, and let him fly, he flew back to Texas, to Dallas, and he had a few short – one hopes happy – years, working at times again with Margo, designing the sets and costumes to those other worlds they both flew away to, as often as they could – a few short years, and then they both flew away, and only memories remained. Sweet birds of memory.

Those were difficult times. Frightening times. It was then that the three of us in St. Louis – me, Clem, Our Cellist – grew from our single Hawthorne apartment, where we had lived happily for some years, to the three in a row that would mask our true lives just enough (we hoped) to deflect certainty, if not suspicion, should the need arise; then that we went to openings and galas with women on our arms, instead of each other, women of our circle, amenable to such deceptions; then that we studiously altered the pronouns of our weekend adventures, and our hopes and dreams, when recounting them to all but our closest friends.

The need for such deceptions – such “gay deceivers,” we sometimes called them with grim humor amongst ourselves – rasped our spirits raw, especially so after those roaring days in Paris in the 20s, and even the more muted ones of New York and Houston in the 30s, days when the “Pansy Craze” made the trappings and haunts of our lives not just a risqué lark, but even a thrilling escape from the depressions and prohibitions of the times, for us, but also even for “normal” folks mired in “normal” lives. And then the years of war, when so many might be – so many were – dead decades before their time, so the call became “do it – whatever it might be – while you can!”

But then, the war beginning to look as though it might someday end, and with victory for the Allies, attitudes began to change. It shocked me one morning late in 1944, as I opened my Houston paper (which I continued to receive even though by then a St. Louisan in both geography and mind) to read of a “nest of homosexuals” purged at the University in Austin, students and faculty – and even administrators, not themselves homosexual, but perceived as too inclined to look the other way. Reputations tarnished, careers shattered, lives turned to torments.

And, of course, such terrors did not happen only in Texas, though certainly plenty in Texas welcomed them, and turned them to political advantage with lightening speed. But not just in Texas; everywhere around the country, and at an accelerating rate. We three lived in less peril than many, already settled into our lives, and two of us with incomes not tied to jobs that could be yanked away if rumors spread, or if newspapers sought to boost circulations by listing names of neighbors “nabbed in unsavory places.”

It may have been, I couldn’t know for sure, just such a “nabbing” that left poor sweet Lorin costumed in San Quenten stripes – so I saw him in my mind’s eye, at least, whether he actually wore stripes or not. But in those times, possibility easily transformed to certainty in the dark, fearful hours of night.

But now, thank God, those times and fears were far behind us, and the young, like those boys I’d seen this morning, walking hand-in-hand on West Pine, and the reader at Habs House, and all the others, would never know them. And even those of us now old would know them only in memory. If the arc really does bend toward justice, then surely the future would not repeat the past.

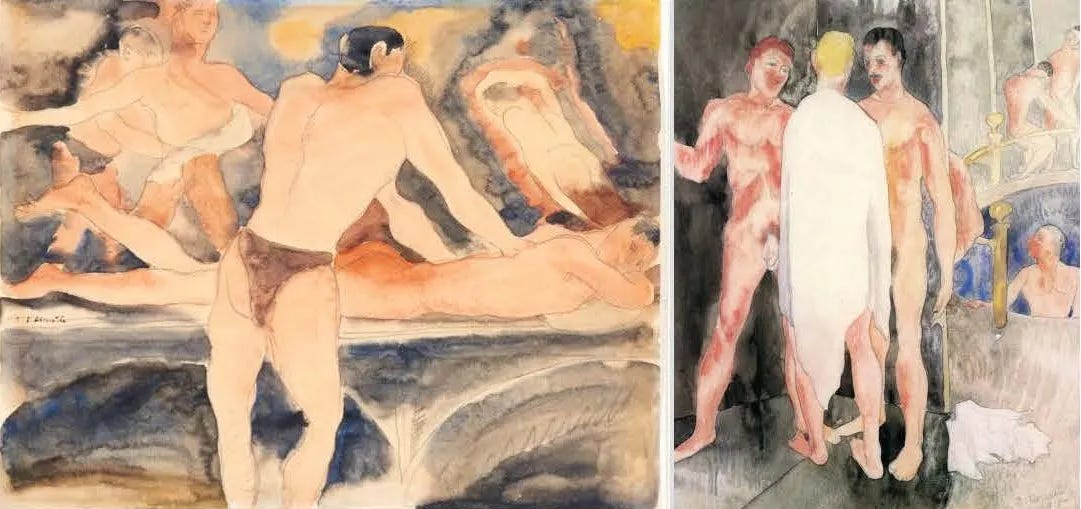

Lorin in happier days, and one of his works, now lost with all the rest.

Part 8 - Glitter and Be Gay.

In the evening I might go to Café Balaban for dinner. I had not feasted on their Beef Wellington for a while - much too long. They had a table for one near the kitchen - a less attractive corner, but cozy – that now seemed to have my name on it.

And after dinner, to the bar up McPherson, the “wrinkle room” where I would be sure to find Fat Albert, the former banker, sitting on the bar stool nearest the window, for views of street traffic as well as the bar crowd.

Albert would be nursing his drink as he did every night, and chatting up Jamie, the cute, curly headed bar tender who everyone, young or old, chatted up, with the hope of something more than chat later on – even though rumor had it that he was “all potatoes and no meat.” How coarse we could be, and what glee we could take in the coarseness, never mind how sophisticated we liked to think ourselves. But for one as cute as Jamie, such a rumor hardly detracted, even if true, and who knew for sure that it was true? Not I, nor anyone I trusted to tell true tales.

Albert, called Fat Albert in a slightly mocking, but also an endearing way, since he was pretty much a good guy, only normally lecherous, and also in a fearful way, by all the slim young things perceptive enough to see their futures as they walked by the bar, and Albert, on their way to the less wrinkled Potpourri, and, they hoped, paradise for at least that night – or maybe longer, though not counting on it. Albert, who, 50 years before, had nursed those same hopes along with his drinks.

A wrinkle room, yes, though not officially a gay one. A sophisticated – some might say, snooty – Central West End wrinkle room, very different from the slightly seedy Onyx Room, and Golden Gate, and Red Door, in mid-town, near Grand Boulevard; or the places I’d heard of in South St. Louis, both seedy and sordid – so I’d heard, though I couldn’t testify to it from personal observation, since I, a sophisticated (or was that, snooty?) Central West Ender, who had spent his twenties in Paris, and his thirties in New York – and, oh yes, the Houston years – never went there.

Oh, all right, occasionally, in the old days, when an evening of slumming seemed to be the thing to do. Even Clem and Our Cellist sometimes found such evenings titillating. I certainly wouldn’t have gone South alone, without them. We always went such places together.

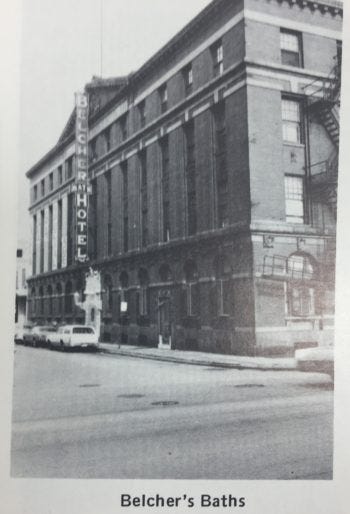

Though I suspected that each of us might sometimes have gone other places alone. Very rarely, but sometimes, trawling for trade in some of the utterly debauched dark and dingy dives near the riverfront, downtown. The spots that Tennessee had alluded to that afternoon of his first visit to our apartment, in 1943. Even perhaps, including visits – extremely, extremely rarely – to the Belcher or Stadium Turkish Baths, where bathing took second place on the program, though proved extremely pleasant (even necessary) after the conclusion of the first order of business.

The baths were, after all, not far from the train and bus stations, which brought the in-transit masses through the city, especially battalions of young men in uniform during the war years, stations themselves offering little to occupy what could have been tedious hours between trains. Things were so much different now that airplanes had almost completely supplanted trains and buses. And now that youth – my youth, at least – had so thoroughly capitulated to age. But, oh the memories. What a blessing for an old man to have the memories, and at the same time how taunting at the moments (now also very rare) when an ember of youth tried, feebly, to flare into flame again.

Thinking of those places, I went back in memory all the way to Paris, and that time between Clem and My Cellist, when I first discovered those similar places, and things that could happen there – the same now and here, as then and there, though with a French accent then. The places that Proust had frequented – he must have done: how else could he have brought them to life so corporeally when he used them as models in writing his Sodome et Gomorrhe? Used them as settings for those sections which still shocked me a little, and then had shocked, and titillated me, immensely. Even though now I’d done my own research into such places, in Paris, and New York (sometimes in the company of that scamp, Demuth), and Houston, and, I admit it, St. Louis, it still shocked me just a little that such things could happen in such places in every city in which such places existed at all.

The Victorian in me still blushed thinking about it. And how could there not be Victorian in me, since that great Queen – I smiled thinking it – still reigned when this queen of lesser rank was born. I smiled, knowing that it was a bon mot that Clem would have laughed at hearing, and at which Our Cellist would have pursed his lips and shaken his head at how puerile silly old American queers could be – even those he loved. How I missed his French superiority, and Clem’s hearty laughs. But no, I wouldn’t let sentimental tears run my mascara this day. Even though I wore none, this day or ever, I wiped the tears away with my finger as soon as they welled.

On second thought, maybe I would have lunch at Balaban’s instead of dinner. My table for one might seem less empty then. And instead of Beef Wellington (why test gastric stamina?), one of Adalaide’s famous crepes, still on the lunch menu, left over from the early days, before the place had become a St. Louis institution, and flowed out over the sidewalk in a French Second Empire fantasy. I could still follow it with a wrinkle room visit. Fat Albert was almost certain to be there, even in mid-afternoon. I could have a beer with him, or maybe just a coffee, though that might wreak havoc on a nap, so maybe just a seltzer instead.

Such dithering brought to mind a line from T.S. Eliot: “Do I dare to eat a peach?” The day had been when I gobbled peaches (and other things I now warmly blushed to recall) without any hesitation at all. Though as I now, and for many years past, diagramed the sentence of such memories, I found that that phrase, “had been,” took the main place on the top line, and “gobbled” modified, far below.

I smiled thinking back to diagraming – one of the more pleasant memories of my schooling, and not altogether useless, though now long abandoned in classrooms, I suspected. And part of the smile came from knowing that it no longer really bothered me that “gobbled” had fallen so far. I still had the memories, and I treasured them, even as I breathed a bit of relief that, since I had them, I no longer had to lament not making more, of that particular sort.

Yes, lunch at Balaban’s instead of dinner. In part, because I’d worked through my list already, had nothing left to fill the afternoon, which, in the sentimental mood I seemed to be in today, might be filled with frequent opportunities for tears to well, tears needing to be wiped away.

Solitary, sentimental old softies needed long lists to fill lonely afternoons. I’d learned that lesson since our apartment had become mine alone. But making long lists, day after day, is challenging, even absent tears to blotch the ink as the lists are written. Today, it seemed, for me, too great a challenge.

Another line came to mind: “Glitter and be gay,” and I tried to feel the mirth of the song it came from. I didn’t now, but maybe later. Maybe Fat Albert could help me feel it. Worth a try, I thought, as I quickly wiped another tear from my tired, glistening eye.

Part 9 - I Wasn’t Always Old, You Know.

The April sun poured through the windows as I looked around the room at the objects that had furnished our lives together, and now furnished my memories.

There was the Japanese netsuke, in the shape of a perhaps pregnant rabbit, that Our Cellist and I had bought as a present for Clem on a significant birthday, ending in a zero. Not that all birthdays aren't significant, and precious, the more so as the number mounts up.

The little ivory creature looked up at me with the sad eyes that had captured all our hearts the instant we'd seen them in the shop at the St. Louis Art Museum. Those sad eyes the greatest treasure I'd discovered in any museum in any city in a lifetime - and ours to be taken home for a few dollars, and treasured for that part of a lifetime that remained. We three had treasured the eyes together, and now I still treasured them, alone.

There was our cello, standing in the corner where Our Cellist always put it. And had put it once again the last time he brought it home from the last rehearsal that would not lead to a next concert, for him.

I looked around the room for my contributions, and there were some, but the one I now hoped to find, the one I hadn’t thought of in years, I didn’t see, and I didn’t remember where I might have put it. A box, decoupaged with cancelled postage stamps, by a dear friend (now long departed herself), into which I’d put all the most treasured letters from my past, love letters some of them, or brilliant (scandalous) literary tours de force of gay sensibility from another age – put in the box for safe keeping until they might become treasures again in the old-age days of memory.

Those days had now arrived, and I would have liked to fill my afternoon with reading the letters again – a perilous undertaking, perhaps, on a day when sentiment already threatened to swamp reason, as it did so often now. When the perils of passion have long ago evanesced with time, looking back at such letters can be bittersweet and exquisite, even with (perhaps especially with) tears. It had been years since I’d looked in the box. Years since I’d seen it even, but I knew it must be somewhere. Hidden away for safe-keeping, or to keep the contents from the eyes of even my two great loves – even though some of the secreted treasures had come from them.

Some, but not all. Others had contributed too, letters only for me to see. Mementos of a life mine alone that it seemed important I guard, even from those dearly loved. Not from duplicity or shame, but as proof that “I” had been before “we” had become almost all – and reassurance that “I” could be again now that “we” had gone.

But I couldn’t remember where I’d put it, and such lapses frightened me now. If memory goes, what’s left? A concern only for the old, of course, since the young have such few memories to forget, and the hubris to think they never could. Or is it the hubris of the old to think we know how the world must be for them?

If I left off thinking about it, maybe it would come to me, sometime, where I’d put the box.

I walked over to the window and looked out toward the Executive House Apartments across the street. A “modern” behemoth that had been built in the 1960s, much to our consternation, since it obstructed our view of the vast stretch of city going out to the south as far as one could see. All of us in the Hawthorne had complained mightily at the time, of course, but such complaints, from those of us who were only citizens of modest influence (and negligible wealth), had no impact when directed at real estate developments of Executive House scale. I’d learned that lesson in development-mad Houston, and found no need to revise that view after my move north, even though St. Louis was not quite so deeply planted in the pockets of her developers.

But after all, Executive House was not such an eyesore, once old eyes had time to grow accustomed to it. Certainly uglier buildings had been built. We even came to enjoy that, from our 17th story windows, we could glimpse the pool on the west side, and the tiny specks of Speedoed young men sunning themselves around it on fine sunny days such as today. From such a height, we could dream all of them into tan, muscled Adonises.

I could see six such Adonises today, one in his tiny red Speedo displaying all he had to offer, to all who might care to see. And it now only April. By summer, there would be dozens such lovelies, hardly any of them there to swim. Swimming might have its place, but not at that pool on a sunny Spring or Summer day. On such days, that was a site for finding love, or satisfying lust at least; or, for some of us, watching and remembering other days and other places, when those finding (or looking, at least) had been us. Temps perdu.

Watching them now in their Spring preening, I almost opened the window to call down to them, “I wasn’t always old, you know.”

But I didn’t. Such a pointless gesture.

The too-secret location of the box of treasures did not come back to me, even with my clever ploy of diversion. Such is so often the way with our clever tricks, especially those we try playing on ourselves. Regardless of what the psychiatrists would have us believe, we really know the tricks we’re playing, and so how could they possibly succeed?

Like the trick I tried out when I told myself I could continue on alone without tearful thoughts of those gone, the life lost, if only I mustered sterner stuff from deep inside. I doubted there was any of that sterner stuff, however deep, deep inside, to muster. I would go on – no doubt of that – until I didn’t, but not without the tears – from time to time.

Today, I’d collected my shirts from Sam Wah; I’d gone to Habs House; I’d written the checks. The routines that were themselves clever ploys to convince me that my life still had a plot. There are many fundamentals in life that we do not appreciate until they’re gone. Routine is one of them. How often I’d bristled, after a while of our ménage, that we’d each come to have our parts in the life we shared, and each expected all of us to keep playing them. How often I’d wished for some disruption to shake us up, and shake us into lives, if not more “thrilling,” then at least less routine.

And then the disruption came, as it does to every life eventually, and what I’d have given then (would give now) for the return of the routine.

Something more to yell out the open window. For whoever is there to hear.

Rather than words comes the thought of high windows:

The sun-comprehending glass,

And beyond it, the deep blue air, that shows

Nothing, and is nowhere, and is endless.

From “High Windows,” by Philip Larkin

Part 10 - How the Big Story Ends

Starting stories is the easy part; ending them is hard. Even though we all really know how they’ll end from the beginning – at least how the BIG story ends – we do our damnedest not to admit it, to ourselves or others.

What possible good could all this looking backward do? None, surely, and yet we old moths fly to it anyway. A fool’s effort to weave the disparate threads of life into a whole cloth before the end. A life’s winding cloth?

Often, in those later alone days, I felt as though adrift without a compass. More Jonah than Ishmael, I did not so much long for the sea at those damp, drizzly November of the soul times, as feel that I’d been grasped by a sinister hand and flung into it. A good enough swimmer, perhaps even better than most, I’d made it far into life, had grown old, when many others had not had the chance to do so. But some days I almost wished I hadn’t either, wished the waves or the big fish had been more methodical in making an end of me. A quick painless end, ideally, though I imagine that neither drowning nor digestion would be that.

So far, the feelings had always passed before I jumped aboard the ship on that last long voyage – or jumped off it. And I felt pretty sure they always would, since, for most of us such thoughts are only melodrama. For most of us, but not all, as I had painfully learned a time or two. But for me, melodrama, surely. No cause for alarm.

But even melodrama, and pretentious references to literary classics, didn’t always make filling empty days – and nights – easy. On some of those days, like an adolescent with pimples about to pop, I felt as though I stood out for my defects, a spectacle of imperfections, which myth says we grow comfortable with with age.

I knew I was old, mirrors and arthritic joints left no doubt of that; and I knew that I should have come to that old-person peace (or reconciliation, anyway) long before. But on those difficult days, in those old years, I struggled to do things most probably do when they are young - write a first novel, read a classic for the first time, figure out my place in the world. And struggled to do it alone.

But, NO! This simply wouldn’t do. Only an hour before, as I had walked to Sam Wah and watched the young men ahead, hand-in-hand, on West Pine, I’d had thoughts of bliss. And now, musings of lonely last voyages – whether melodrama or not.

Get up. Get out. No more of this. Perhaps that lunch at Balaban’s would help dispel my “hypos,” make me a touch less “grim about the mouth.”

I picked up the stack of checks to be mailed and took them down to the lobby. Perhaps I hadn’t already missed the postman. Though I wrote the checks so promptly – another of my old-man quirks – I had no real reason to hurry getting them mailed.

Writing the checks had been one of my jobs in our three-way division of domestic labors, almost since the moment I joined the household. Our Cellist had been hopeless at it, and even Clem, a man of business, though “retired,” could blithely write a check without even a glance to be sure the account would cover it. I even wrote the checks on those rare occasions when I went away alone. Wrote them, and left explicit instructions as to when they must be mailed.

Instructions not always followed, as I found when I took my first such solo adventure (until then), to Houston, in ’53. The by then world-famous Tennessee would be there directing someone else’s play, a first for him (The Starless Air, by his friend and sometime collaborator, Donald Windham), at the Playhouse Theatre, the Main Street venue created by Joanna Albus, protégé and close friend of Margo in earlier days – though in those earlier days she’d used a different name, a character still in process of creating herself – as were we all – then, and I supposed, always.

Tenn invited me to be his guest and guide. Though I would be a guide in need of guiding, since it had been almost 10 years that I’d been away.

I went alone. Clem had no interest. Our Cellist might have enjoyed seeing this new part of America – provided we added a day or two in “Nouvelle-Orléans.” But in the end, his performance schedule did not have room for even a short trip, so I went alone.

Just as well. Houston was no longer the city I remembered, and sometimes had the wistful thought I might return to – especially in those years when the snow piled high along West Pine, and the cold wind blew straight down from the Arctic.

I wouldn’t return, of course, for anything more than a visit. What was there to warm me now in Houston, aside from the sun? Certainly little to warm the soul. By then my soul-sun shown in St. Louis. That became clear in just a day or two. And I went back north with no regrets.

Over the years I heard that many had gone: Mrs. Cherry at 95 (1859-1954), from the rigors of a long successful life; Margo at 44 (1911-1955) from kidney failure, poisoned by a lethal mix of alcohol (the hard drinking kind) and carbon tetrachloride, the one from partying, the other from carpet cleaning, together a fatal cocktail; Lorin at 51 (1918-1969), from who knew what, perhaps the crushing of hopes and dreams of one stout enough to survive San Quinten, but too fragile in the end, to survive the world. Others gone from my life, if not the world, but not gone from memory: Gene, Cardy, Forrest, Russell – more and more. Going seemed to be on the to-do list of so many as the years passed.

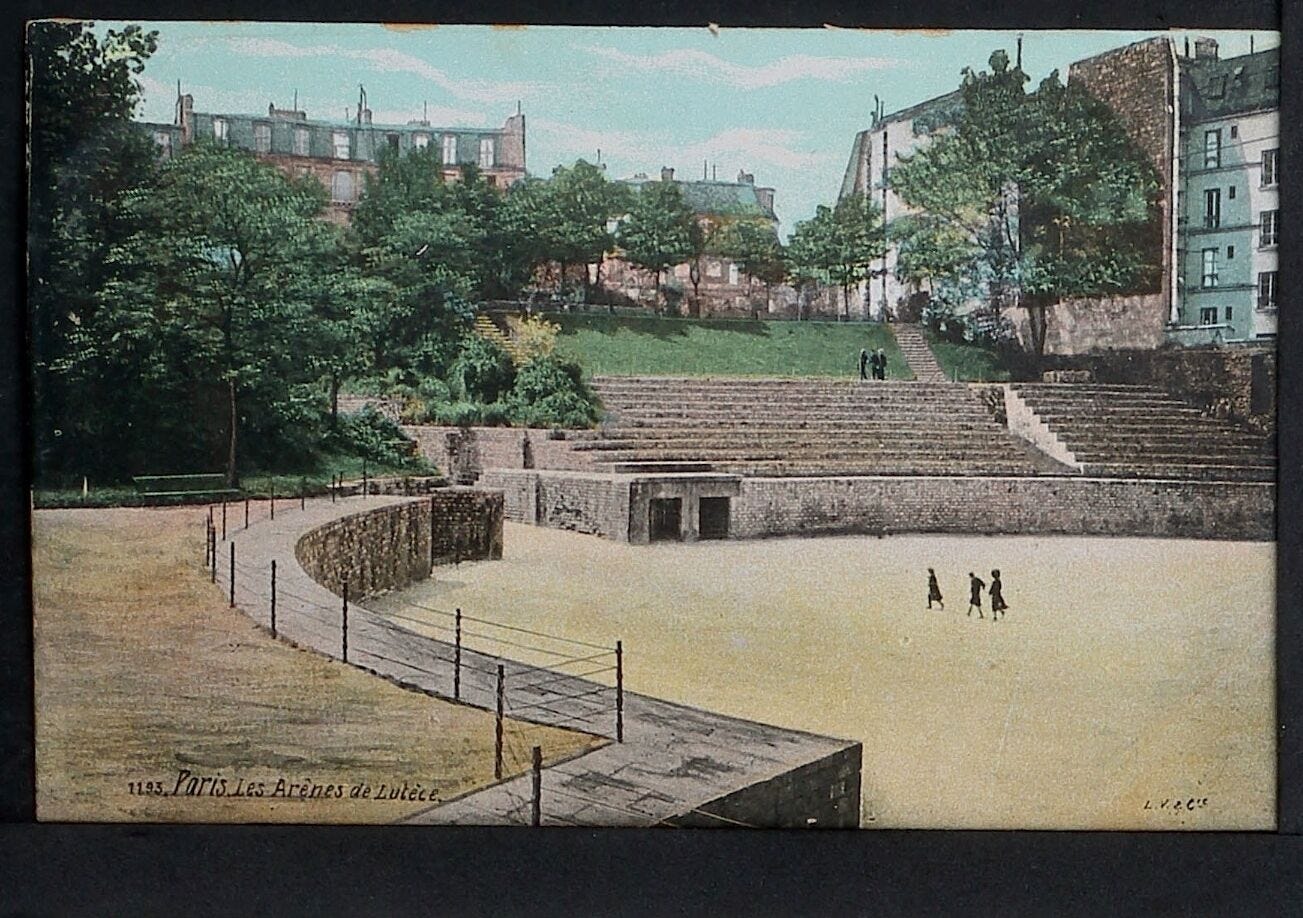

Then the great tragedy of the great loves gone. First Our Cellist. Clem and I took his ashes back to Paris, as he’d asked. We took him with us to revisit the places we’d first known together so long ago. To Café Gaudeamus (now gone), where our table in the back did at last have room enough for three. To the garden of the Madame, her garden still beautiful, but now gone herself. To the Arena, where we all remembered his beautiful music. We left him there.

Soon, back in St. Louis, Clem gone too. His family took him to the family tomb in Chicago. At their request – their insistence – I stayed away – cried my goodbye tears alone.

And then I was again only one, as I had been at the beginning.

As I locked my door, I saw my new neighbor unlocking his – to one of the studios we three had made ours while we still were three. There had been no reason for me to keep it – or the one beside it. One apartment now seemed almost too big. And so I had let the others go.

I knew that someone had moved in. Jimmy had told me that, though he knew little more to pass on. What a surprise now to see this new neighbor – the young reader from Habs House. My heart raced a little when I recognized him. And my cheeks turned a little pink, as though I’d been caught in my clandestine watching. I went down in the elevator wondering what the cosmic forces might be trying to tell me with this improbable coincidence.

By the time I reached the lobby, I felt a little dizzy, a little out of breath. I put the envelopes in the collection box – all but the one for Bissinger’s – I’d deliver it by hand on my way to Balaban’s.

I nodded to Jimmy, standing sentinel at his desk by the door.

“I saw my neighbor,” I said.

“Yes, sir, he has moved in. Such a young man, and polite. Perhaps like you when you were young?” and we chuckled.

When I was young, I thought. When I was young.

I sat down in the chair by the window, where I’d sat not so long before. Sat, to catch my breath a bit before I walked up Euclid to McPherson, to Bissinger’s and Balaban’s. Sat to think back a little to those days when I was young, and all the days that had been my life between then and now, all the places and people. Old moth to the flame of remembering. I took a deep breath, and propped my elbow on the awkward chair arm and rested my forehead in my hand. I closed my eyes – they watered a little – perhaps allergic to the spring pollen – surely not tears.

No need to hurry to lunch. I had all afternoon. And no one else would want the chair. I felt weary. Perhaps more weary than I’d ever felt before – as we sometimes say. Though who can remember all their weary times to know that’s true? Weary enough, anyway. It would do.

Maybe I’d take the time for a little doze. Why not. I had all afternoon. And the checks were written and mailed. And no one would be awaiting my arrival, either eager or impatient. And as the breeze gently lifted the white curtains into the room, the memories might almost transform into dreams …

CODA

“Get over here quick,” he said, the instant he heard the receiver picked up at the other end.

“The old guy next door – the creepy one who was always looking at me at Habs House – died – sitting in the lobby for fuck’s sake – so his apartment is available – the two bedroom next to me. If you two get it, we’ll have our own little ménage here in the Hawthorne – like nothing the old maids – and old bachelors – have ever seen before. So get over here!”

That was the way you got an apartment in the Hawthorne, an almost elegant survivor from the Roaring 1920s, trending more and more queer in the Sexy 70s, as the Central West End of St. Louis turned into the out & proud gayborhood of the city. You got it by rushing to the manager’s office with your application and deposit check in hand, almost before the hearse pulled away, as soon as you heard that one of those old maids or bachelors had dropped dead. It helped to know someone who already lived in the building, who might even get a glimpse of the corpse, and let you know, before word spread through the neighborhood – as it always did, like lightning.

And so he called his “friends with benefits” (debauched, delightful benefits) as soon as he got back up to his apartment, from the lobby, when he heard the sirens. Yes, there was the corpse. Jimmy confirmed it: the old guy next door.

“Old Mr. …,” Jimmy said. Who’d “lived in the Hawthorne for 30 years.”

He hadn’t caught the name – and he didn’t hang around to ask twice. It didn’t really matter anyway, since obviously he’d never be getting to know him now.