Left Bank on the Bayou - Not an End, A New Beginning

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

For most of us life is not a symphony. It does not build inexorably toward a crescendo and a cymbal crash. For most, it goes along for as long as it does, and then it ends, “not with a bang but with a whimper,” as the poet said. Eliot, that St. Louis boy I heard about during my own St. Louis days – who went into the world to change it, and did, though most of us whose world he changed may know little of him. He went to London, I to Paris: he never fully left St. Louis behind; perhaps I would never fully leave Houston either.

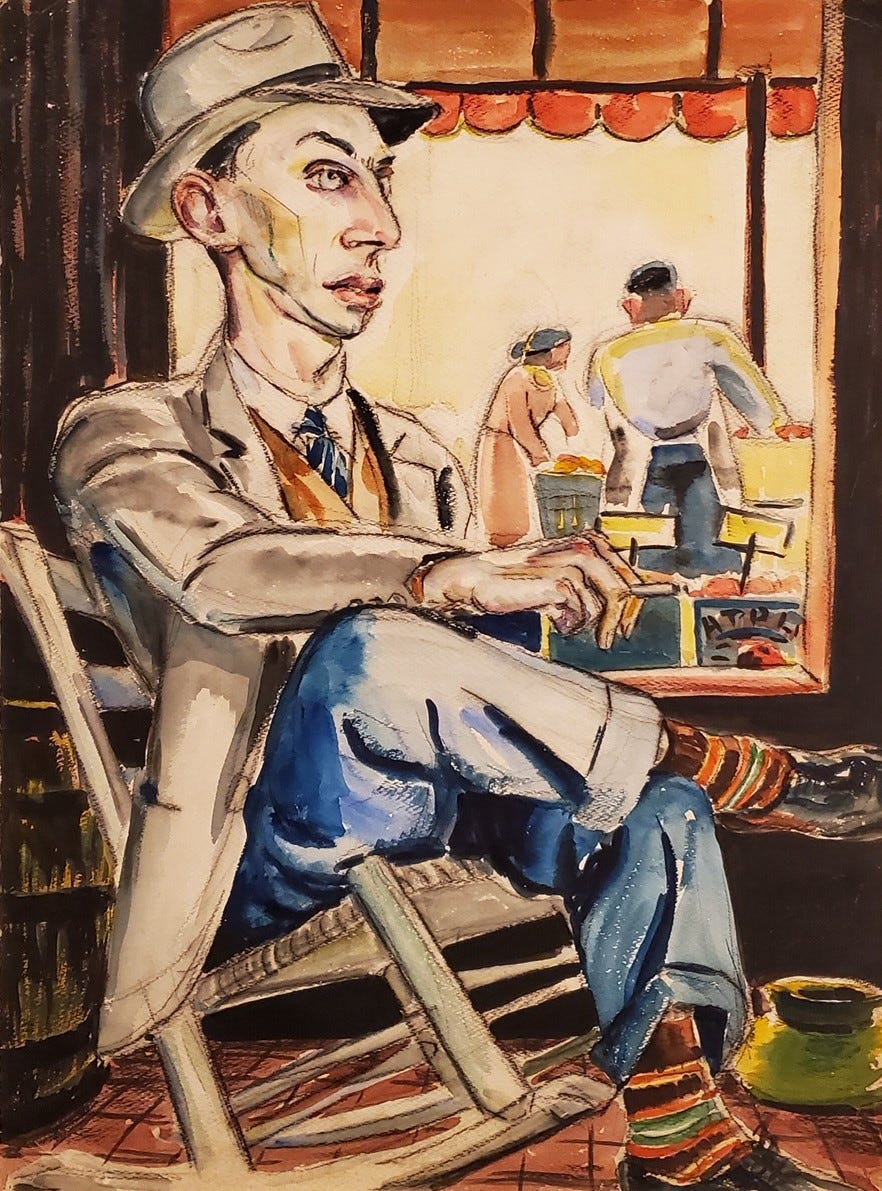

When I reached the house, I found Russell’s drawing of me, and his note, together on the dining table. I had no idea when he’d put them there. Clearly before the exhibition opening. I’d gone directly from a meeting of the library board to Forrest’s gallery – had not gone home first, had met him there; so he had known the whole evening what I would find when I got home; it made my consternation all the greater:

“I leave you this as a fond remembrance of our day in Seabrook, and of all our days and nights together. You said you feared it revealed too much. What it reveals is the splendid man I loved – and love still, even though no longer with him. I hope that you can still love me too.”I went into our bedroom and saw his half of the wardrobe empty. His toiletries no longer sat beside mine on the bathroom shelf. Back in the dining room I now saw that his painting no longer hung above the mantel. Perhaps I would put grandma’s chromo there again. (A decision for another day.)

Sometimes the most harrowing journeys are those of the spirit, the soul, the inner self – whatever you choose to call it. They’re the ones that, in the end, must always be taken alone. I now had the disheartening sense that I was taking up that lonely journey once again – and I had no understanding why.

In a few days a letter arrived, this time with a smudged postmark I could not read. I sat at my writing desk holding it, as I had done with that other letter from Santa Fe so many months before. Again, I dreaded reading it even as I longed to.

When I finally summoned the courage to open it, I read:

“By now you may be asking Why? Perhaps look to your beloved Proust for hints – to his Narrator’s life with his Albertine. (I know we both believe it was more likely an Albert than an Albertine!) The Prisoner is the one I mean. I offer this not as reproach, but as possible explanation you’ll readily understand because from Proust.”If only Proust were still writing to tell me, even in his circuitous way, what it was that Russell meant. But Proust was not still writing, and Russell had gone – had left only memories, and his note, and his portrait of me – the portrait that may have told too much, but did not tell what I now most wanted to know.

I sat at my desk with his letter in my hand, determined that I would not shed tears, because tears brought no answers with them.

I wished that Mrs. Cherry had come back from San Antonio, and family, for another stay in her Cherry House – now emptied of life with the death of Mr. Cherry, and emptied of vibrant art with her temporary (we all could hope) absence from Houston as she grieved her way through that loss. She might know what to say to me that might help me now.

Gene and Cardy and Forrest and Margo were all too young and confident of their splendid futures (in life and love as well as art) to help me through my own grief now, or even understand the help I needed.

But of course I knew that no one could help with such grief, at such times.

As so often at such times – and, in truth, there had been too many such times in a life I fool-heartedly liked to think clear-eyed and level-headed – I took up my pencil and wrote, as much to fill the oppressive minutes while I struggled against the tears, as to write sentences of understanding or reproach.

Without the address he had not given me I couldn’t post my reproaches (or my questions) to Russell. Though in my heart I had no desire to send reproaches. Reproaches would only taint the memories that seemed likely to be all I’d have left of our beautiful time together. Beautiful, even though cut short for reasons I could not imagine, let alone comprehend. Not now. Maybe never.

I began a letter to Wilma – still in New York, still longing for Parker – a letter I knew I wouldn’t post – wouldn’t finish – wouldn’t even continue beyond the pathetic opening: “Oh, Wilma, yes, again …”

And then, with Russell’s letter, with its smudged postmark, beside my paper I wrote:

Why am I writing this? I’ve lived a unique life – we all do – but not a remarkable one. Unlike Eliot the Poet, no histories of my time will be likely to include my name. So why am I writing this?

I’m writing it to remember – and perhaps to be remembered, for a moment at least. To remember that there was a time when I could feel so deeply that it seemed the feeling would burn up body and soul in a conflagration of feeling.

Other writers write for other reasons, I know. But for me, it’s always to remember. Even when it’s fiction it’s not made up – it’s remembered, with other names. Or sometimes, the same names. Even with heartache and pain – and with joy too – these are the memories of the life I’ve lived, all that’s left of that life, the gossamer remnant of a life that now seems almost done.

Why are you reading it? You’re reading it because … But who am I to tell you that. You must tell me that – or rather, tell yourself .

At first I wrote, “If you are reading it,” – then I deleted “If.” Because you are reading it. That makes a point of contact between us at this moment, no matter if it’s an instant after I wrote, or a hundred years. A contact that I need so desperately now. At this moment, as you read, we share a spark, the spark of life as we touch – like scuffing across carpet – scuffing across life.

These things happened, are now history. I write about them to remember. But they are not the end. They are a new beginning – the hope of one, at least. They have to be. For now, what else is left?Such self-indulgent musings are good for filling empty spaces in life if for nothing else. And such writings – reams and reams – did fill the empty next few months for me. Our house – now once again only my house – now seemed as empty as Mrs. Cherry’s. I wished that I had a San Antonio of my own to go to; Houston, and this house, now had nothing to offer me, it seemed. But where was my San Antonio?

I heard that Russell might have gone back to Santa Fe. I would go there. I heard that he might have gone to New Orleans or Mexico. I would go there. I heard that he might have gone to St. Louis or Chicago. I would go there. Wherever he might have gone I would go, if only I thought I’d find him when I arrived.

And….I’m in the story and breath- held waitng to fond out. ..