Left Bank On the Bayou - Russell On His Way

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

Our little Houston “Bohemia,” as Bertha Louise Hellman (an artist herself – making a name as a painter of Magnolias) had dubbed it some years earlier, had by now grown fully into the term; and in many ways it had become a Queer Bohemia, to boot. It took only the briefest introduction from me for Russell to be on his way in our little “Bohemian” Houston avant-garde art world.

He’d learned to find his way in so many worlds – from New Orleans to China to Santa Fe – that making a place for himself, wherever he was, had become easy for him. And based on what I’d heard him describe, and what I’d seen myself in Santa Fe and now Houston, wherever he was, took him in with arms as open as mine had been that day of his arrival. A mysterious allure which seemed to say, “I will let you be part of my circle – but only because I choose to,” made him irresistible. And so others flocked around him. How I envied that aura, I who often felt slightly out of step with those around me.

I also found myself a little jealous of him, after the first exquisite days, which we had spent only and entirely with each other. Those days I knew could not last. Probably even I would have grown weary of them if they had. But I did feel a pang when I took him the first time to Forrest’s studio for a rollicking evening of introductions, talk and laughter with a few who I knew would find him as irresistible as I did.

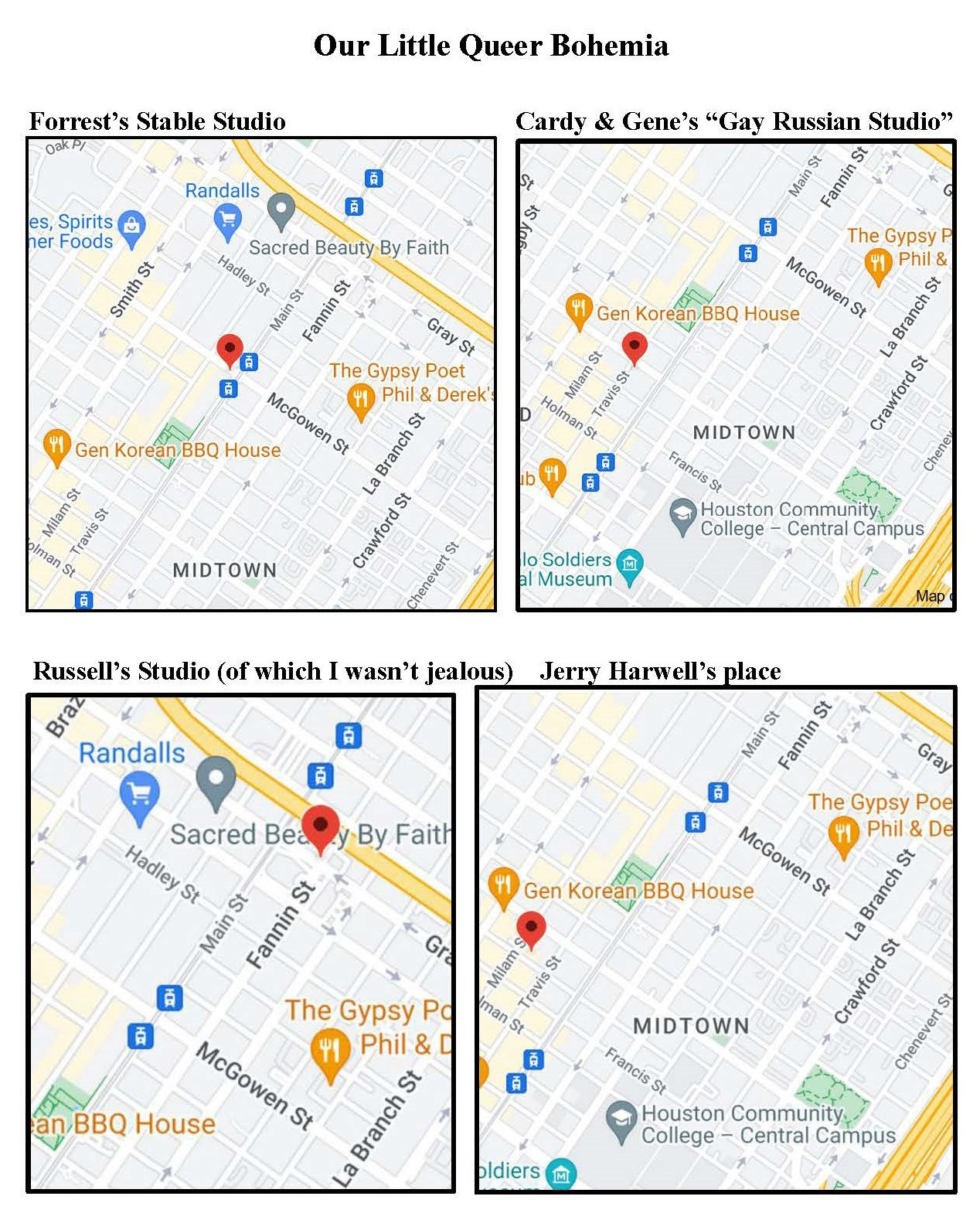

Forrest had rented an old stable behind the Joseph Carter mansion on Main Street – of the rich lumber Carters – and renovated it into a studio/gallery where he lived, made art and showed his own work and that of others – all three words, lived-made-showed, applying equally to the art and the life, since for Forrest, art and life united into a single thing.

He said that he had come to Houston, from his hometown of Bay City, in search of other men “like” him. Indeed, he had found such men – “like” in certain, essential ways – and his stable/studio/gallery had become a meeting place for several of us - even though Forrest sometimes lamented that he still felt slightly out of place: too “butch,” as they say in some circles of some more cosmopolitan cities. Perhaps in Forrest’s case an issue founded more in his psyche than reality.

It was true that Forrest hardly evoked the effeminate, as did many in the circles I’d frequented in Paris and New York, and now to a degree even in Houston. While some of our like-inclined brethren tended toward the fey, Forrest emphatically did not. No limp-wristed lisper he. Though in fact I’d encountered much more of that in New York and Paris than I ever did in Houston. It was not a pose that readily found a place in our Bayou City.

Forrest’s personal angst over the struggle of the “butch” and the “fem” within himself, took him to a theory (everything seemed to take Forrest to a theory!) as he sought to relieve the tension the struggle spawned within him. In his vision, all things sought to converge into ONE, including male and female, and helping that convergence along had become a life quest for him. One shuddered to hear some of the avenues he envisioned for achieving that convergence, shuddered and felt queasy. But certainly his theories would always be only theories. Surely no one would really do the things he bluntly talked of, involving surgeries to unite the male and female in a single body – his body!

By contrast, Russell – fluid as a willow, solid as an oak – seemed to feel no unease at all as to his synchrony with his world. It baffled me how anyone could be so at ease, so certain. It seemed to enthrall Forrest, and certainly intrigued others of our circle.

That circle included Gene and Cardy, of course, their “Gay Russian” studio on Travis Street, where they also lived together, as they had done for years, only a short walk away. A new man, Jerry Harwell from Fort Worth, now working in finance, but intent on making a place for himself as an art critic, had his “garret” on Stuart Street. Some of Margo’s leading men shared apartments (and lives?) nearby – Del Pepin, with his movie-idol good looks, and Robert Halff (they talked incessantly of going to Hollywood and stardom!). Even Russell, though he still lived with me in my house in Quality Hill, took a studio on Fannin Street, near Forrest, where he could have the space of his own that he required for work, and solitary intervals – though he made clear to me that I need not (must not, if we were to thrive together) be threatened by it. Call it Bohemia, Greenwich Village South, Left Bank on the Bayou – call it what you would, we found there a space where we could learn to be “ourselves” in the company of other men “like us.” And we knew how rare such places were, and so not to be taken for granted.

One fall evening, as we shared glasses of passable wine in Forrest’s gallery, Gene said to everyone in general, “We are a movement of some kind – whatever it is. They fit together, our pictures. After all we saw, Cardy, on our trip to Europe last year, I know that all we need is paint and canvas – and more artistic freedom – and if anything – this is slightly an understatement, I’m speaking of capability from inherent talent and the spark that makes a picture more than just another picture.”

A murmur of agreement met his words, even though his meaning may only have been half understood.

“I have the feeling that all of these things have much more importance than we know. All of it – every little piece of the puzzle, I feel, has some element that says, ‘this will be part of the inside story.’ And when I feel that, I feel that such a load is on my back – and I almost wish that I were just another unimaginative, uncreative human. But the fact blares out – We’re NOT. And so we trudge along bearing our cross.”

Even Gene could not suppress a smile at the conceit those words revealed. And then he concluded with a crescendo and a climax.

“There’s a new era in painting, and we’ve got to ride in on the crest of that wave. It belongs to us. Though we may need to go to New York or Paris, and paint like hell! It is ours – and we’ll do it. If only we’ll be willing to suffer the thing out. That keeps one alive.”

I thought, in my slightly jaded way, how invigorating it can be to bask in the boundless hope of youth, even as I remembered that the bravado of such statements from the young mask doubts as often as they proclaim real confidence. Perhaps that was not the way it was for this group of talented, young, queer men, making their art in what some – or maybe most – in Paris and New York would call a “Bayou backwater.” But even with his confident words, Gene let a hint of doubt escape.

I glanced at Russell, who had seen the world, to gauge his assessment of Gene’s views. I half expected that he’d have a knowing half-smile on his lips, the weary eyes of one whose dreams of youth had endured the slings and arrows of living. I might have seen that on my own face looking in a mirror – on those difficult days that we all have sometimes, anyway. But what I saw on Russell’s face (was I surprised; no not at all) was a look of love – compassionate, not carnal – that said, “Live your dreams, even if all around you seem intent on waking you from them.”

Of course, I saw this on his face because it’s what I wanted to see there – to see that this man who was so much the substance of my own dreams, still believed in dreams himself – that he would join me in them even in the face of this dream-battering world. Having seen the world too, and the toll it can take on dreams (oh, Clem; oh, my Cellist; oh my dreaming young self), I wanted to see that my hope, with this man, might not be just a dream. And so I saw it. Even though with a hint of doubt – just a hint, as had come along with Gene’s words. Do we ever, after conception, have a moment without at least a hint of doubt?

I didn’t say any of this, in part because I didn’t want to give it substance by saying it – but also because the room was so full of things being said that there was no need – or space – for more.

It was uncanny the way Forrest and Gene so often opened their mouths to speak at the same time. They seemed to have a special bond (as artists, that is; Cardy needn’t have any fears of infidelity – unless it might be the infidelity of art). “Don’t both talk at once!” one felt like scolding them. But in the next minute they’d be running over each other like puppies yapping, as though there weren’t words enough between them to say everything they each had to say.

And that’s how this evening drew to an end, with Forrest insisting they could do everything they needed to “right here,” and Gene persisting, “But there’s a wide world out there.”

I thought, as Russell and I walked the few blocks back to his studio, to get my car for the drive back to Quality Hill, and as our hands touched – touched but did not clasp, not here, not even on this dark street of our Bayou Bohemia – there’s a wide world here too, if we let ourselves live in it. And as Russell and I drove home, I dreamed of living in it with him, what that might be like – even with a hint of doubt.