Left Bank On the Bayou – Santa Fe Summer

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This post continues the sequel to my novella The Song of the Amorous Frogs: A Story of Paris in the 1920s. Click the title to catch up on that earlier story. It is now 1937. Our Narrator has returned to Houston, after his youthful Paris years and loves, followed by 10 years, and undoubtedly more loves, in New York City. And so his story continues … You can catch up on Left Bank parts already published by clicking the LEFT BANK tab on my cover page navigation bar.)

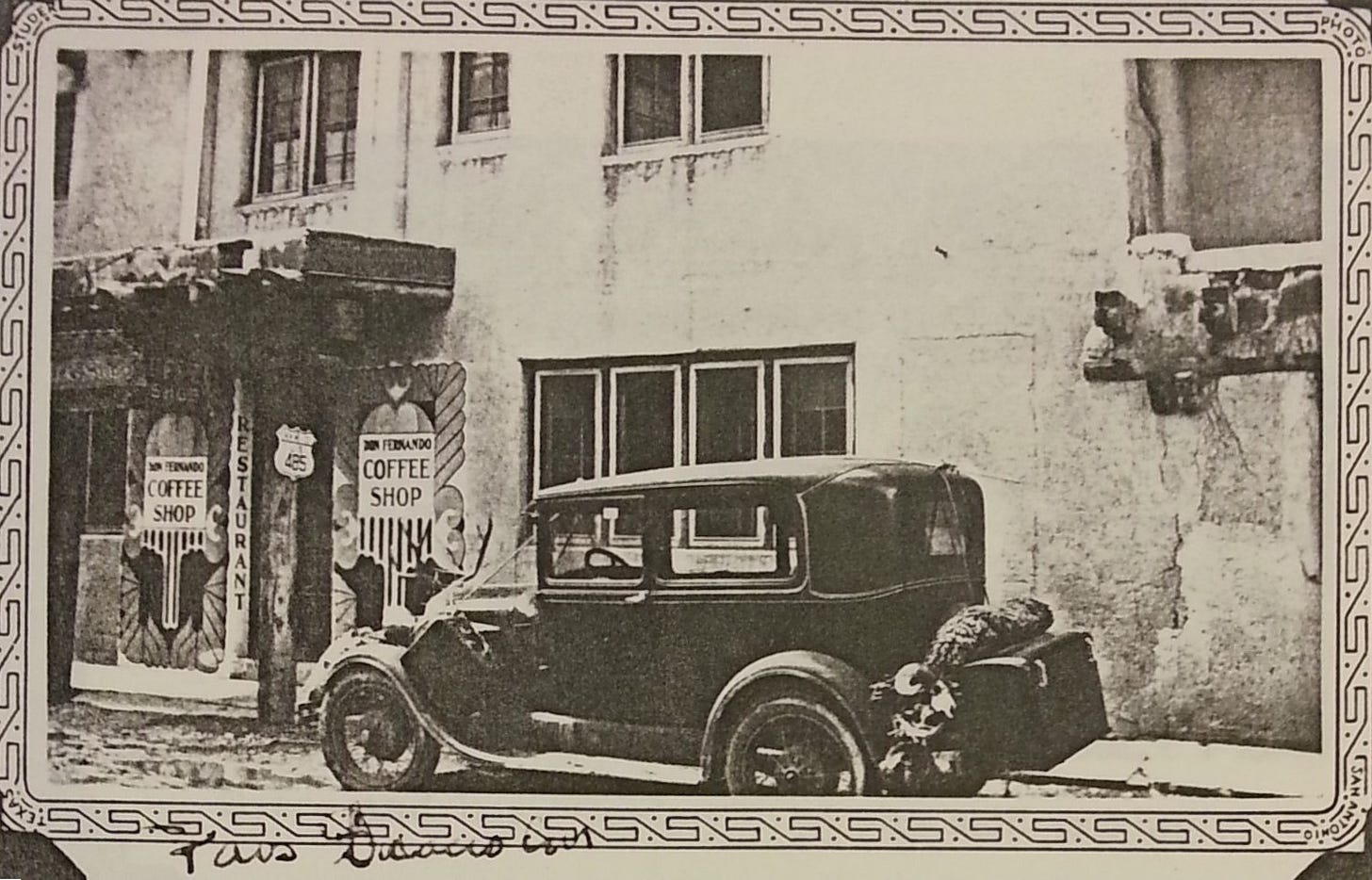

A summer in the cool high desert, of cool tall drinks drunk in honeysuckle scented, hollyhock encircled gardens, of evening mesquite fires crackling in kiva fireplaces, within thick adobe walls, need fear no competition for our affections from the heavy, humid Houston heat, for those who could afford the journey and the stay. (And, of course, with Billy there I might be looking at more warmth than even the crackling logs could promise. Hope springs eternal.)

But such daydreams can survive only when there’s no reality intruding to burst them. And that proved not to be the fate of my Santa Fe daydreams that summer. Billy made clear early on that he would be otherwise occupied. Grace was somewhat irritable at the tepid reception of her most recent exhibition – some of her Mexico paintings, which should have been in vogue, but had to hang against powerful works by the actual Mexican artists – a stop in Houston of a national tour changing minds and eyes when it came to what art could be. Pretty no longer seemed enough, and pretty seemed the lifeblood of Grace’s art. Beulah, a grandmother who had come to art late, after she’d finished her duty as daughter, wife, mother, was her usual steady self. But she could not keep the crew rowing the same direction by herself.

After a few rocky days, I too sought to be occupied otherwise, and found such occupation sometimes on late-night strolls in the Plaza – or (I’m embarrassed to say) in the shadows of old adobe churches a time or two, with those who knew the churches, and their hidden nooks and crannies, well. Holy orders do not preclude all interaction with the world, it would appear.

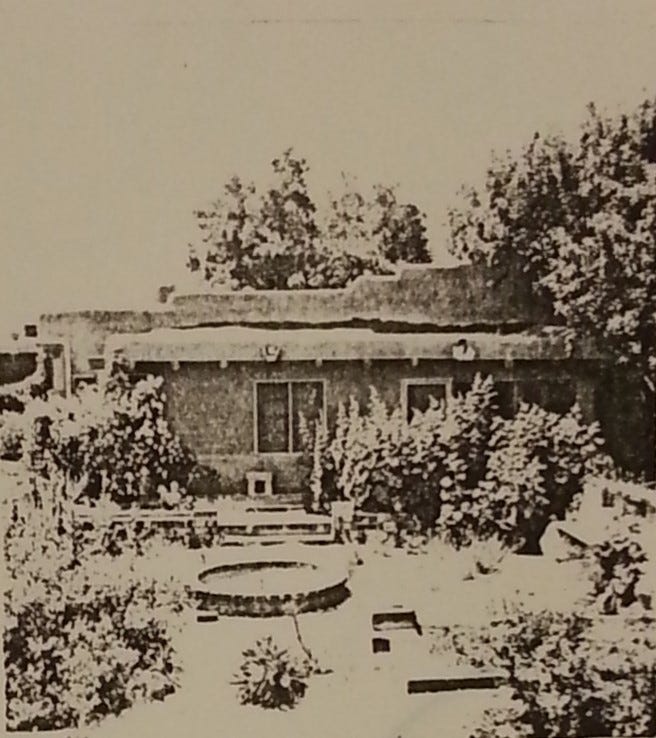

We had pooled our funds to rent the Gerald Cassidy house out Canyon Road, a long, but pleasant walk from the Plaza, a walk offering many interesting possibilities most evenings. Cassidy had died in 1934, leaving the house available to be rented. It was more than ample for the four of us, though one must be discrete even when sharing large houses with knowing friends. And so I never took new friends there, making the long dark stretches of Canyon Road all the more appealing.

One evening, after a small dinner party at Witter Byner’s house – the one he shared for decades with his lover, Richard Hunt – the notorious (though mostly ironically so) Spud Johnson filling the fourth place at the table – I decided, instead of going directly back to Canyon Road, to take a paseo through the Plaza. I needed to walk off a bit of Byner’s delicious dinner (Richard’s, I think, more accurately), and let the more than drinkable wine breathe the night air. And at that hour one might even make new friends; some men become so friendly at that hour, after glasses of drinkable wine. I felt in a particularly friendly mood myself.

And so I walked down to the Plaza, and around it and across it for a time that I trusted was not too long, but long enough for my potential friendliness to be apparent to any who might be feeling friendly too.

After a while of walking, I noticed a man sitting on a bench, watching me as I strolled. About my age, or perhaps a few years older – but not disqualifyingly so. Strong features; greying blond hair. Starched shirt opened a button or two; chinos crisply creased. Our eyes met, and then, after a long moment, glanced elsewhere, as eyes do at such times and places. But then they met again, and again, until neither of us had any doubt that we were both feeling friendly that night, in want of new friends – one anyway, even though it might be a brief friendship only. Time would tell about that. But at such times, for such men, brief friendship may be friendship enough.

And so I smiled a discrete smile and he discretely smiled back. I nodded toward the empty other end of the bench on which he sat, and he nodded to agree that it was empty – but needn’t be. I sat, and we exchanged observations about the splendid, cool evening. Almost before we knew what was happening, we were becoming the best of friends – at least for the evening – against a wall in a dim deserted side street, steps from the Palace of the Governors. Such things can happen on cool summer nights in the high desert, and elsewhere, if you let them.

This turned out not to be a friendship for that evening only. He told me his name – Russell D., and I remembered it. From New Orleans as much as any place, but recently returned from China and Japan, where he’d written oriental observations for American newspapers. An artist himself, it piqued his interest hearing that my summer housemate was one of the leading artists of Houston. Houston, he said, might be a town he’d want to try out – from all he'd heard since his return from the Far East. Could it use another artist, did I think? Yes, indeed, I thought so. And I knew all the contacts he’d need to find his footing there. I could even facilitate his first contacts by introducing him to Grace before any of us left Santa Fe.

I should have known by then to be wary of such a rush of enthusiasm for a new “friend.” Years of living and scores of such friends should have taught me. But life doesn’t work that way. Which is all I really know for all my experience. And so I invited him to come for drinks some afternoon soon – which he did the very next afternoon – and I introduced him to Grace and Beulah, with whom he made an instant hit, and Billy, who held out a little longer – observing, appraising, sizing-up – before he too approved.

Thus Russell became a regular visitor to our Canyon Road casa, for afternoon drinks, chez nous suppers, and, when the drinks had flowed down the throats too freely to make possible the long walk back to his rented room near the Plaza, for overnight stays, sharing my bed, which all tacitly agreed to understand as entirely chaste. Even Billy pretended to understand it so, though once or twice, after evenings of especially plentiful drinks, his barely veiled flamboyance suggested that he’d be willing, if invited, to join us in making it less so. But that might be a step too far even with housemates as sophisticated as Grace and Beulah. I made as clear as I could that it would certainly be a step too far for me, and Billy acquiesced, at least as far as what might happen within the confines of our compound. What happened elsewhere, of course, could be no one else’s business, aside from those directly involved in the happening.

By the time we packed our bags and began the long drive back to Houston, all understood that we’d be welcoming Russell as a new Houstonian, as soon as he could complete remaining business in New Mexico – a mural he’d agreed to do for Mabel Dodge Luhan’s Taos house – of an arroyo gushing with water after a flooding rain – a sight he’d never seen, but thought an intriguing paradox for a near-desert setting. Mabel, a distant cousin of mine, through New England ancestors, many generations back, found Russell, and his Far East stories, so intriguing that she agreed to his unlikely mural suggestion.

One evening – it would be our last together for a while, and my last in New Mexico that summer – we, Russell and I, made our polite excuses and prepared to leave Mabel’s dinner party early: we had such a long drive back to Santa Fe from Taos, and I’d be starting that long drive back to Houston in the morning. Ever the vivacious, cordial host, Mabel said she understood, and walked with us to the door.

“We must do it again next summer. Won’t that be fun to look forward to?”

During the evening, after drinks and wine aplenty, she had made her play for Russell – and not succeeded. But ever the philosopher, whose philosophy seemed to be “Nothing ventured, nothing gained,” she did not hold grudges – not about such things as that. As we walked to the door, she bid us an exuberant farewell, and hinted to me, with a look, that she knew the situation – and thought it splendid that at least one of us would be keeping such an “intriguing” new find as Russell “in the family.”