Left Bank On the Bayou - Opening Night

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

I had hardly stepped through the door of the tiny gallery on a mild May evening when I heard the forceful voice of McNeill Davidson coming from my left:

“These boys were very unhappy when they came to me – misfits socially and didn’t realize why. Starved, yet didn’t know where to turn for expression. I understood their needs because of what Mrs. Cherry had done for me – and so, like her, I shared untiringly all I had, travel abroad, books, materials, my very soul so that I might be able to open that door for them that she had opened for me.”

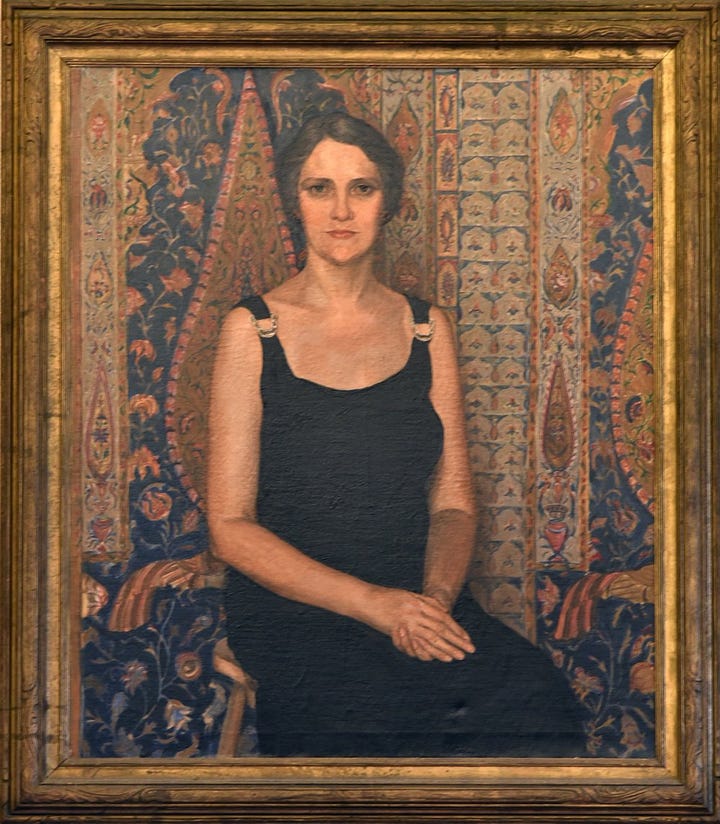

When I looked that way, I saw McNeill standing before a “wild” (for Houston, a very wild!) painting, with Miss Julia Ideson, Head Librarian of Houston Public Library, her longtime friend, and also a longtime supporter of art in Houston, opening her library to the artists and the singers and the actors of the city, for them to fill the already crowded walls and the small stage with their art.

McNeill spoke in her dynamic way; Miss Ideson listened quietly, but intently, and looked closely at the wild thing on the gallery wall before her.

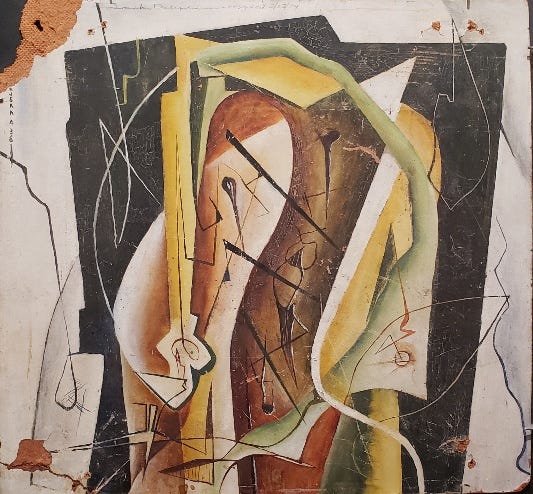

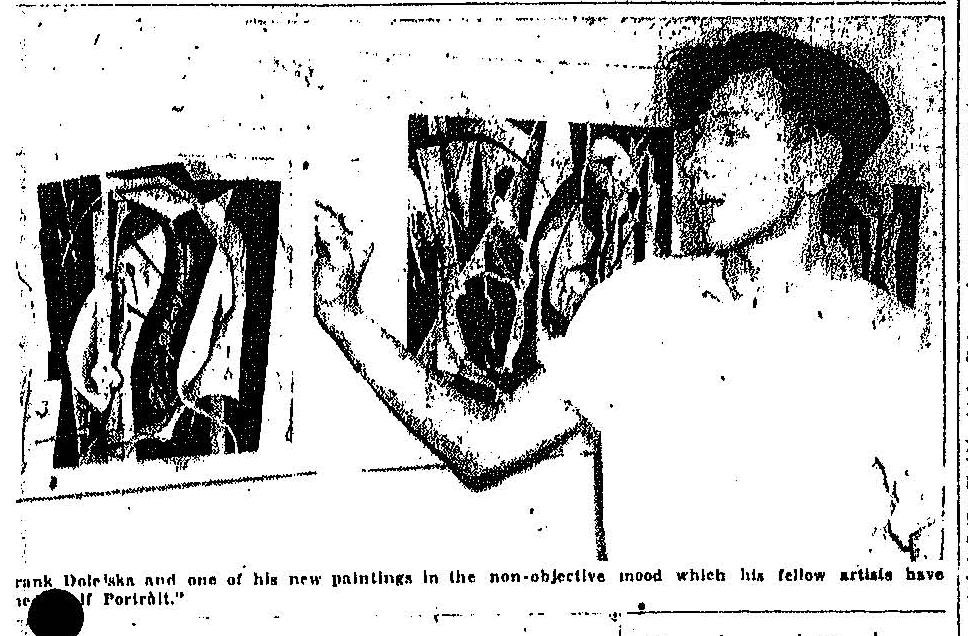

“This one is by Frank Dolejska. He calls it Revealed – Self Portrait. Can you imagine how his art teacher at Reagan High responded to that!? Because he’s hardly out of high school, you know. He and Robert Preusser, and Dean Lee – you’ll see their work here too – all three from that same school and all three making work so advanced it would make art heads even in New York explode. What could I possibly have to teach them? I merely allow them to discover themselves.”

She said this with deep satisfaction as their encourager, their validator.

“I received an invitation from Miss Onderdonk, Eleanor, in San Antonio, asking for an exhibition of my youngsters, at the Witte Museum. Of course it is all because of Mrs. Cherry’s enthusiasm and appreciation for the new. She spreads word of them there even in her grief. My boys – I call them mine because a part of that most important part of them, their art, is mine, I feel – have the swellest show to be sure – better and better, as you can see around us, and I am happy with them. Robert made New York in the All American Exhibition – and only 19 years old! That kid never misses. Next year I take him to Chicago to study with Moholy-Nagy at his School of Design – the New Bauhaus. Frank is running him a close second, if it is a second.”

The two moved a little further along the gallery, to look at other paintings, and I continued my discrete eavesdropping.

“I’m proud of my older boys too, Gene Charlton and Carden Bailey. They also do amazing things. They were with me in Europe last fall – the two I introduced to you when we had the happy pleasure of running into you and Ima Hogg in that lovely Paris bookstore. Do you remember? As supremely talented young men – I really can’t call them “boys” as I do Frank and Robert – they have fine careers ahead of them. Gene especially. He already has the confidence of a master, which I hope the younger boys will grow into. And now another man, Forrest Bess from Bay City, has joined us to expand our vision of what art can show.”

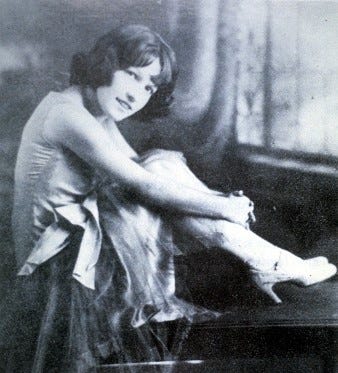

Almost as an afterthought she added, “I mustn’t slight my inventive girls, Maudee Carron and Nione Carlson. They are excellent artists too.”

I smiled at this bias towards boys her remark revealed – especially poignant since she had herself known the dispiriting barriers that time and place and expectation so often built to keep women from their art.

With a dramatic flourish, she continued: “Wish I were so I could desert my duties as mother, wife and caretaker to the dear old aunt, and join Robert in that world of excitement in Chicago, and soak up all the art riches that will nourish him there. Alas! I am but the gang plank for the shore and boat – stretching myself full length that those on shore waiting may walk over my prostrate body and sail out to sea!”

All this overhearing took place on the opening night of the first exhibition at the gallery of “non-objective” art that Davidson and her band of avant-gardists had organized to show their own art. Who would have thought that artists in Houston made enough such outlandish art (outlandish anywhere but Paris, and perhaps New York) to fill a closet, let alone a gallery?!

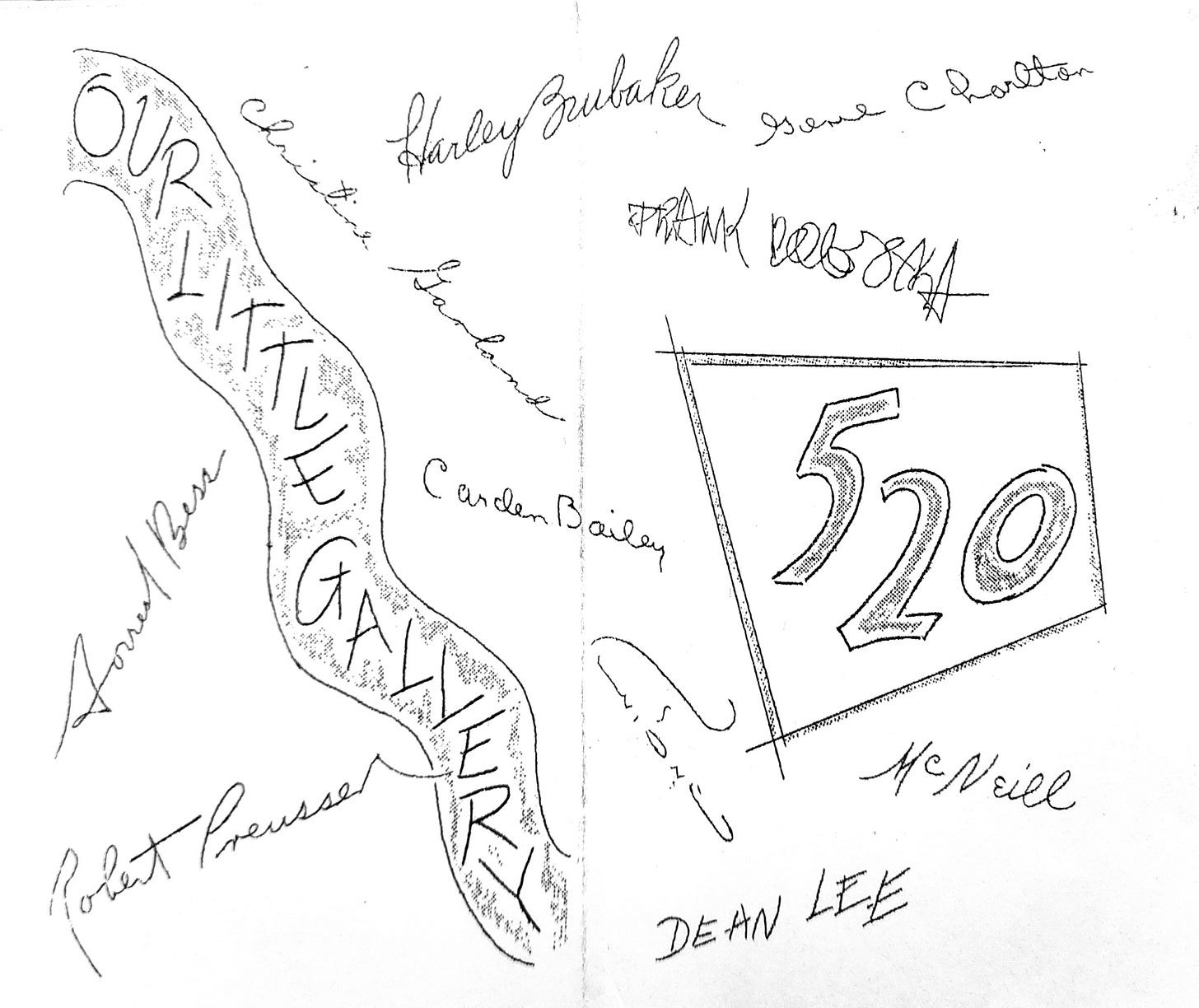

But here it was, ranged around the walls of this new 520: Our Little Gallery, as they called it after the address of McNeill’s house, in a conscious nod to the now gone Gallery 291 – named after its address also – where Alfred Stieglitz had introduced New York, and all of America, to what had then been equally outlandish art. McNeill’s band had transformed her garage into their gallery; she now had to park her car on the street, a small sacrifice for the thrill of showing thrilling art. (I wondered if her husband shared their enthusiasm as he parked outside.)

It was a space hardly large enough to hold the art, never mind the artists themselves greeting the small “crowd” gathered to see this spectacle of abstract art by their fellow Houstonians. I saw Gene and Cardy across the room – and perhaps with them that new man, Forrest Bess. And Nione proudly showing one of her paintings to Billy Goyen and Billy Hart, both matured so much more toward manhood since their college-boy bearing of the year before. Maudee, Port Arthur wild child, seemed to float in her own other-worldly cloud as she talked with her adored friend, Margo Jones.

Grace was not there, nor Beulah, my Santa Fe companions from last summer. But this was not their sort of art, or art scene. Grace might well have been in Mexico – or who knew where? – and Beulah likely had grandson babysitting duties at home. Just as well, since the crowd already filled the gallery almost to fire-hazard capacity. With the weather still mild, some opening night visitors had spilled out onto the sidewalk, wine glasses in hand. (Not the best wine to be found, perhaps, but a fillip of continental sophistication in the wine desert of Houston.)

I had passed Lorin on the sidewalk as I came in – Ed, his window-dresser boss from the department store, beside him. We’d nodded to each other and said, “Good evening.” That had seemed enough to both of us. I did wonder if the two had become more than boss and employee – but then I reminded myself that it was not my business. I almost convinced myself that I didn’t even care.

I missed Wilma. She would certainly have been at such an outre evening, even on a work night. But she had gone back to New York, at least for a while – so that she could pine for her Parker at closer proximity, I suspected, though she would have protested otherwise. I thought for a moment that perhaps I should go back to New York myself. Or Paris?

But no. Not yet. Perhaps not ever. I still had hopes that Russell would be joining me in Houston - and soon, I hoped. Though I started to fear that hope might not really spring eternal, as the saying has it.

Looking across at Maudee and Margo, I saw that one of Margo’s handsome leading men, Albert Horrocks, the most dashing of them all, had come up beside them. She had a stable of those gorgeous leading men in her theatre company; most, though not all, unquestionably queer. I had no concrete evidence as a foundation for pronouncements about Albert – but hope sprang eternal. Should I join them and see if I could gather the missing evidence?

But no. Not tonight. As a younger man I would hardly have had to ask myself the question. As the mature man of the world I had now become, I knew that if the question even came to mind, the answer should be NO. Conquest – and even only “quest” – had become so wearying that there could be no pleasure, no satisfaction, no matter the outcome.

I stayed at the gallery a while longer. I pretended to study the art; I gave congratulations to the artists; I told McNeill of my tea-time with Mrs. Cherry – and joined her in gratitude to that wonderful woman. And then I walked back out into the mild May night to make my way back to the streetcar, and my house, downtown, alone. These days I seemed always to be going back out into the night, alone.

What a sweet but melancholy story!

Your stories of a forgotten Houston Bohemia are eye-opening and gratifying! Thank you for sharing this.