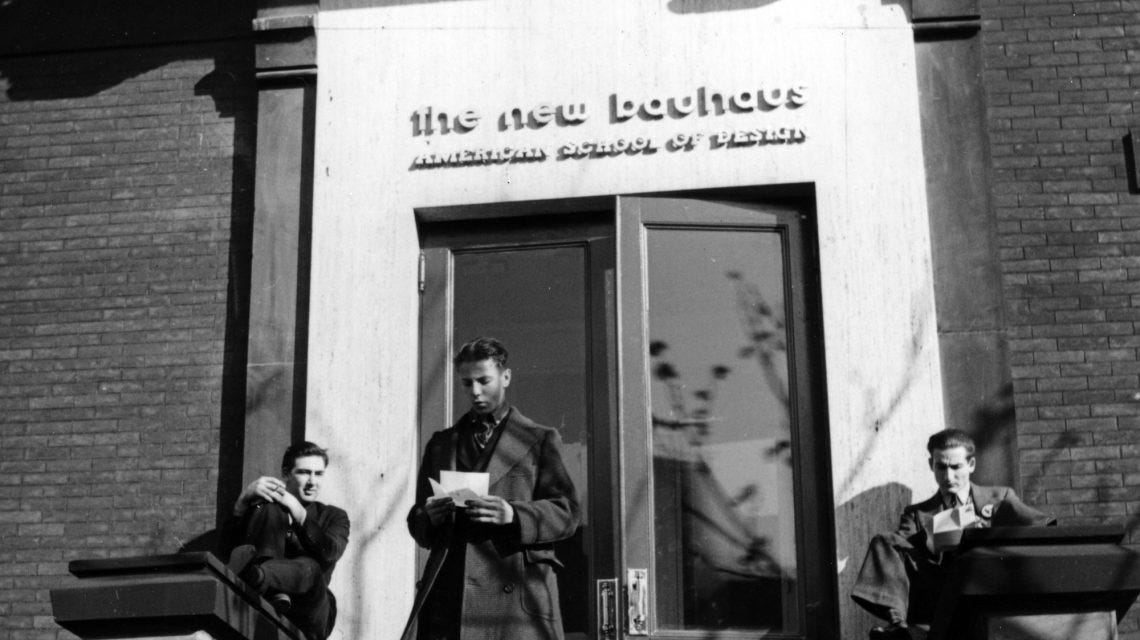

Left Bank On the Bayou - Combined

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

Part 1: Home to Houston

I had come back to Houston from Paris in the spring of 1926 thinking I might stay. But after the banquet of Paris, Houston, then, seemed like a famine. Especially for a man like me, who had discovered in Paris, not just that I loved other men – I already knew that, even long before I could say it to myself or anyone – but also that in a few places, Paris chief among them, it was possible to live life almost openly as a man-loving man, to go through the days and streets with love beside me, no need for hiding or shame. Almost none, anyway – old habits die hard, even in Paris. There had been heartache for sure – first Clem, then, my Cellist, then the two of them together! Though by now I had lived enough and matured enough that I had no hard feelings toward them; I only hoped that they’d found happiness in each other.

But after the paradise of queer Paris (somewhat flawed, perhaps, but still paradise), Houston, in 1926, had seemed intolerable. I quickly sensed that there could be no life for me in the city other than that of my Mother’s son – whether dutiful or rogue, it hardly seemed to matter: either way, my Mother’s son. Oh, certainly I could have skulked off to New Orleans from time to time, and perhaps found a night or two of respite in some French Quarter bar or back alley. But in Houston, only a proper me, a good-boy me, would do; and I knew that after Paris, where I had lived my truth and found I liked it, even though at times it broke my heart, I could not – would not – go back.

And so, after a few months, I’d gone to New York – only slightly better than Houston, certainly no match for Paris, but with the advantage, at least, of being huge, with ever changing multitudes – “City of Orgies,” as Whitman had called it, and still the city of “the swift flash of eyes offering me love” that it had already been in his day. In New York no one had known me from birth, known my people for generations, thought it their right to know everything I did, everywhere I went, and with whom. And, most of all, for me in New York, my mother, whom I loved, but for whom I would never grow out of childhood, was a thousand and more miles away. In New York I could live a life that was more than a constant stream of childish fibs. Though the fibs did still get told during the rare visits home.

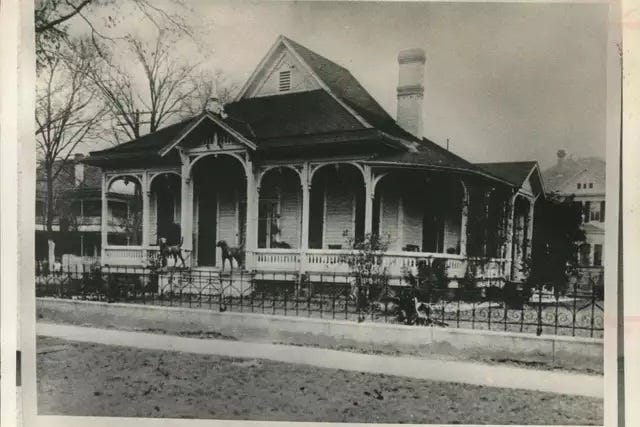

But now mother was dead. My father had preceded her years before, and my sister too, my only sibling, one of the multitude taken by the Spanish Flu back in the teens. She had died before giving my parents the grandchildren they longed for – grandchildren I would never give them, certainly – so I now had no close family in Houston. The family home, built by our grandfather in the 1860s in what came to be called “Quality Hill” – called that by those who built their houses there, at least – came to me, as the only remaining heir, the end of the line, to state it bluntly. Since I’d grown weary of my New York life anyway, I decided to move back to Houston, to live in the house I’d been born in, grown up in, thought I’d never live in again.

I’d even made my childhood room my room again, in part because I liked the view over the garden from the window. I smiled, thinking how such thoughts mirrored the joy I’d felt looking out my window in Paris 10 years ago, over the Madame’s garden – joy magnified as Clem, and then my Cellist, stood beside me also looking, or lingered in bed, calling me back. But, even more, I chose the room again to prove to myself that I’d grown up, that I’d matured enough to not let it keep me the fearful child I’d been when living in it those years before – fearful, most of all, as I became aware of myself and the world, that my parents, my family, my town would see the kind of boy, then man, I was becoming: one whose love “dare not speak its name.”

Houston had grown so much since I’d gone away that the house – my house, as it had become – now sat among businesses rather than the other genteel residences that had been its neighbors in my childhood, or the open fields all around when grandfather had built it. It had become a faded beauty set in the fading remnant of what had tried to be a sort of Paradise garden for a reborn new south, a vision bustling Houston had proved too impatient to let mellow into a local version of the antique New Orleans Garden District. Before too many years I would probably be forced to sell and move elsewhere, perhaps even move the house itself elsewhere, just as Mrs. Cherry’s house had been moved one night in the 90s, from its original site on Market Square, out to distant Fargo Street, then almost in the country it was so far away. The taxes on such a lot so near the commercial center of this now burgeoning city would become too much for my modest income, even adding my inheritance from parents to the legacy left me by my sister.

I would always be grateful to my sister for her forethought in leaving me that legacy at a pivotal time, making possible my life in Paris, a life which had changed my world forever, a life which I’d come to know was indeed the “movable feast” Ernest had dubbed it. I sometimes wondered if she had perhaps known better than I what I would need to become myself, and that she could give me the means for the task, as James had for his “Lady” in his famous novel. I wept that it took her death to make my own life possible – my real life as the man I was, not the man all my history had said I “should” be. Perhaps she knew me better than I could have imagined, and watched over me from wherever she had gone. I saw my life, in part, as a tribute to her too short one, and pledged to myself to be the best, the truest man I could to honor her.

Even her legacy, and the little left by mother, however, would not keep me in the house forever. Certainly the little I earned by my writing would not do so either. It pleased me that I sometimes had poems printed, and that my latest play (after the dozens that came before it), had made its way to a stage or two. But hardly any money came from either poems or plays. And the articles I sometimes managed to sell to newspapers turned into little cash.

But that was a concern for the future. Just as the passing of mother, and all my family, made my reasons for fleeing to Paris, and then New York, a concern of the past. Now my challenge for the present was to build a life in Houston, that I could embrace as my life, and live proudly.

Part 2: Tea and Memory, with Mrs. Cherry

It could be that the best part of Paris is the memory. Because in memory there’s no need to acknowledge the grit of reality, but only the romantic glow of the Paris “we'll always have,” as we'd like to believe it really was.

The thought was not completely new to me, but it came to mind again on a fall afternoon in 1936 as I sat in the antique parlor of a Houston house I had visited a hundred times before, over the decades of my life.

“Do you remember our evening in Paris in 1925?” asked Mrs. Cherry. “When we ate tête de veau, and then went to see Modigliani’s paintings – you for the first time, as I recall – and after that, thrilled to Josephine Baker’s Danse Sauvage premier at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées? What a splendid evening! With Clemmie Tan and your Cellist – and, later, that fellow from Chicago, Clem. How long ago it seems now.”

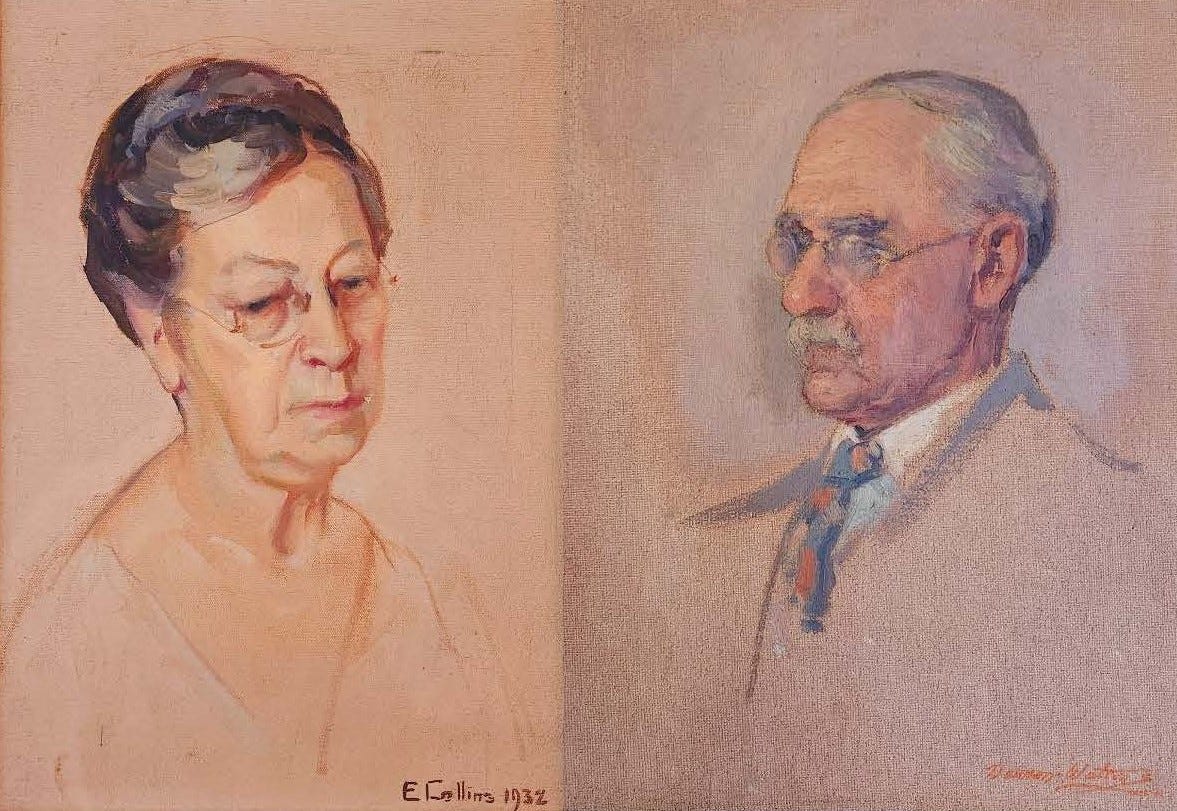

Mrs. Cherry flooded us with these fond memories as we sat in her parlor in “The Cherry House.” That is what everyone called the lovely, white-pillared, Greek Revival residence that Emma Richardson Cherry and her husband, Dillin Brook Cherry, had lived in for decades – much longer than previous owners, William Marsh Rice, namesake of The Rice Institute, or the long-forgotten Nichols who had actually built the house in 1850. We sipped our tea from delicate porcelain cups in the parlor after a pleasant hour in her studio, the place where she painted, of course, but also where she taught the many young Houston artists she had been helping find themselves as artists for as long as she had lived in the house. I had been one of those students myself, years – no, decades – before.

Though not quite so “historic” a structure as the Cherry House, my own house still counted as antique by Houston standards. As I looked around Mrs. Cherry’s room, I thought of my own “parlor” – what an antiquated term in 1936, but how apt for that front room of my family house, not much changed since the high Victorian stuffiness of the 1880s had filled it with uncomfortable, carved and inlaid wood and horsehair chairs and settees around rosewood and marble tables – incoherent blendings of Herter and Belter translated into new dialects as those styles made their way from the showrooms of New York, down the coast and around into the Gulf, to the workshops of New Orleans – and then to the front rooms of Galveston and Houston – showy rooms of questionable taste decorated by grandmothers, like my own now long departed MawMaw, who found themselves, circa 1880, with the means for lavish display – lavish by the provincial standards of Texas at the time – but without the “sensitive” sons to help them modulate it. I smiled, thinking how MawMaw could have benefited from my help – or even more, from that of some of my Paris and New York acquaintances. Still, I had not yet been able to bring myself to change anything about the house; perhaps I never would.

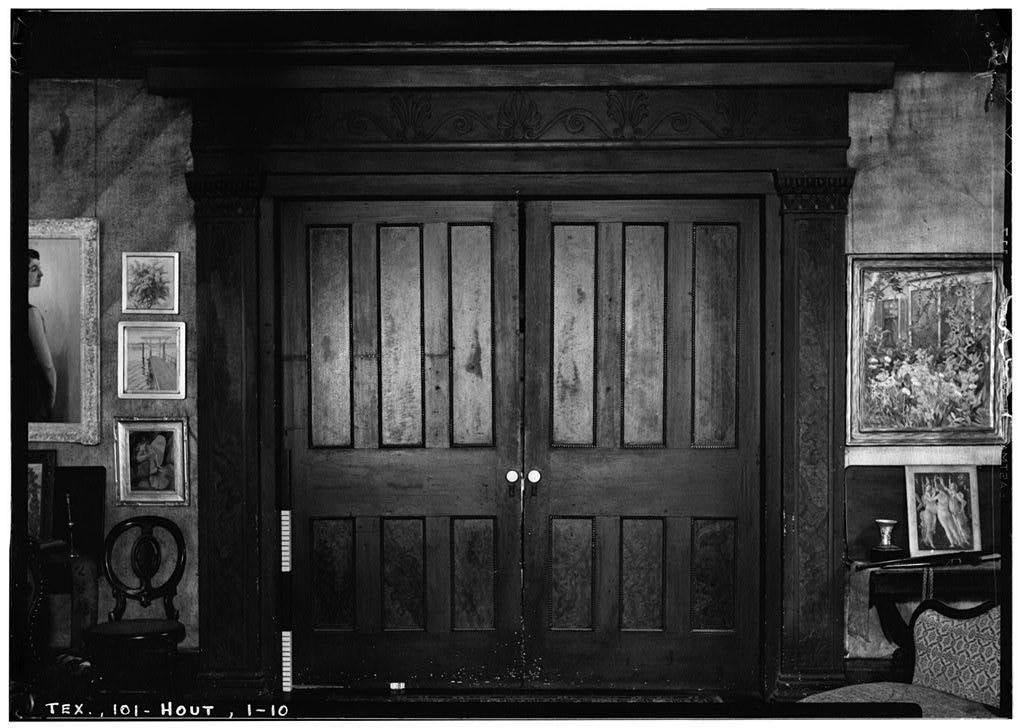

Mrs. Cherry needed no such “sensitive” helpers to make her own room magnificent. Around us, on her walls, hung some of the Cubist studies she had done all those years ago, in Lhote’s atelier, in Paris. Also, other pieces she had done in the 1880s – copies of masterpieces in the Louvre, and her own early Impressionist canvases and watercolors, done at Giverny in 1888 and 1889 – where she had gone to visit Mary Hoyt Seller, her girlhood friend and traveling companion on that first trip to Paris – her companion until Mary met and fell in love with the charming Englishman, Dawson Dawson-Watson.

When Mary and Dawson married, after a courtship of barely the winter months, he took his new bride to Giverny, where he lived in the fledgling art colony developing there – and where Cherry visited the newlyweds, and painted alongside Dawson, at the start of what had become a nearly 50 year artistic friendship. It was partially that friendship which had brought Dawson to Texas years later, to San Antonio, so that he too was now a “Texas” painter. The Dawson-Watsons had even lived some months with the Cherry family in this very house, small as it was for so many personalities and talents.

But her Cubist and Impressionist paintings were not the only pieces on the walls. Fabrics and objets d’art brought back from her studies and her travels filled every inch, things purposefully selected to adorn the “artist’s home” she envisioned for the venerable, historic old house that she loved so much – and which she had made the artistic center of Houston – the center, that is, as far as real creation was concerned, and not just the superficial, showy palaces that all the new oil and old lumber money of Houston made possible for the rich, both nouveau and ancient, of the booming city.

I always found it a nourishing room to sit in – even though stuffed full, and not what anyone would call “modern,” despite its owner/decorator’s desires to be modern, at least in art and mind, herself.

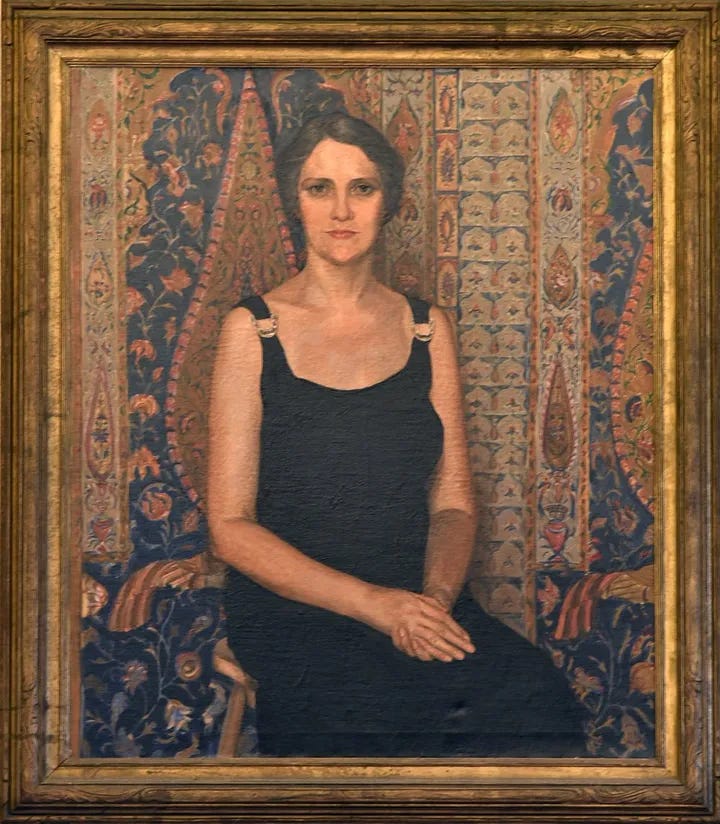

In her studio, she had shown me her latest paintings – wonderful canvases, in which she joined her mastery of color, with impeccable drawing and a long-honed talent for revealing the essence of the people, places, objects she painted, not just their surfaces. In what was already becoming a slightly old-fashioned manner, she always painted “something,” not just the abstract shapes that were becoming fashionable. She’d had her early training in the 1870s and 1880s, from William Merritt Chase and Luc-Olivier Merson, among others, in New York and Paris, at a time when paintings had to depict something. But always wanting to be “Modern,” especially in her art, she had studied modern color theory with Hugh Breckenridge and Henry McCarter, in Pennsylvania; and she had gone to Paris in 1925 to learn Cubism from André Lhote. I had briefly studied with him too.

And she had learned Lhote’s lessons well. She still incorporated Cubist elements into her works when she could, sometimes masking the cubist under-structure with “sheer prettiness,” as she said. Ever the professional, she painted to sell – and, after so many decades, she knew what would sell in Houston. Some criticized her for bowing to her market, for deception. So be it. An artist must eat and have a roof overhead in order to paint – even one who lived her creative life, metaphorically and sometimes actually, en plein air. Mrs. Cherry was no “Sunday painter.” And so she did what her profession demanded, and she did it beautifully.

“You’re right, I think, in coming back to Houston now – now that you can be here in your own way,” she said.

Though we had never talked in detail about “secret” things, being a woman of the world, she knew – as she had let me know all those years ago in Paris.

“I spent years in New York as a young woman, and, if it had been only my own wishes to consider, I’d have spent more time in Paris, perhaps stayed there. I even, for a while, thought of moving to California when my brother, Edward Richardson, went there. But I don’t regret my decision to remain in Houston. No place is perfect, no matter how we see it in our memories or our dreams. I believe in my heart that life is what we make it, taking the good and the hard together, no matter where we are.”

We sat silent for a few moments, both thinking, no doubt, of Paris – perhaps the Paris of our memories and our dreams.

“Maybe Paris seems long ago because it was,” I said. “Ten years! I was so young!”

She laughed the beguiling laugh her friends loved. “I can’t say the same for myself,” she said, “Then or now. But you are still young. What? Thirty-five? And look 10 years younger. So much is still ahead for one so young.”

“What can pass for young, sometimes, in a dim light,” I said, pleased that she gave the compliment, but aware that it was a compliment as much as a reality. Especially aware since I had now fallen in with a younger set – some of them actually 10 years younger – in the art and theater circle that had flourished in Houston since I went away, 15 years ago now, first to Paris, then to New York. How much the city had changed over those years. How much I had changed. Time would tell if the two of us had changed in ways that would make a Houston life the life I wanted now.

Part 3: Bohemians

When I’d left Paris in the spring of 1926, to return home to Houston (Mrs. Cherry had not returned until the fall), I’d been a young man with a bruised heart who could hardly grasp that the fairy tales of childhood had not come true, that my Prince Charming – Prince Charmings, as it had happened – had not prized me, once found, above life itself – that, in a stinging twist not part of any of the tales of childhood, they had found their bliss in each other instead of me. Or I imagined they had, with an ocean between us.

By the time I returned to Houston again, in 1936, no longer young, certainly not nearly so naïve, the heart had grown accustomed to bruises, had accepted them as part of life, along with the leaps of joy and hope that preceded them. I did not believe that I had become cynical or bitter – only more knowing from experience in the ways of the lives of hearts in love, especially for men forced to live warily in a world with little sympathy or room when both of the hearts belonged to men. After 10 years, wariness and weariness had blended so thoroughly that I felt sure even a monkish renunciation of love in Houston, if that was what lay ahead for me there, would be preferable – for a while, at least.

And yet I knew that I would not be living a life of solitude in Houston, nor even a life apart from men like me. I knew because I’d made connections with other Houston expatriates in New York, also going “home” – connections that already promised to go with me back to the Gulf.

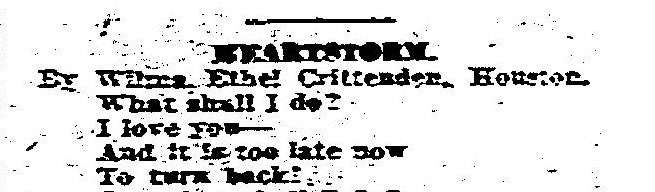

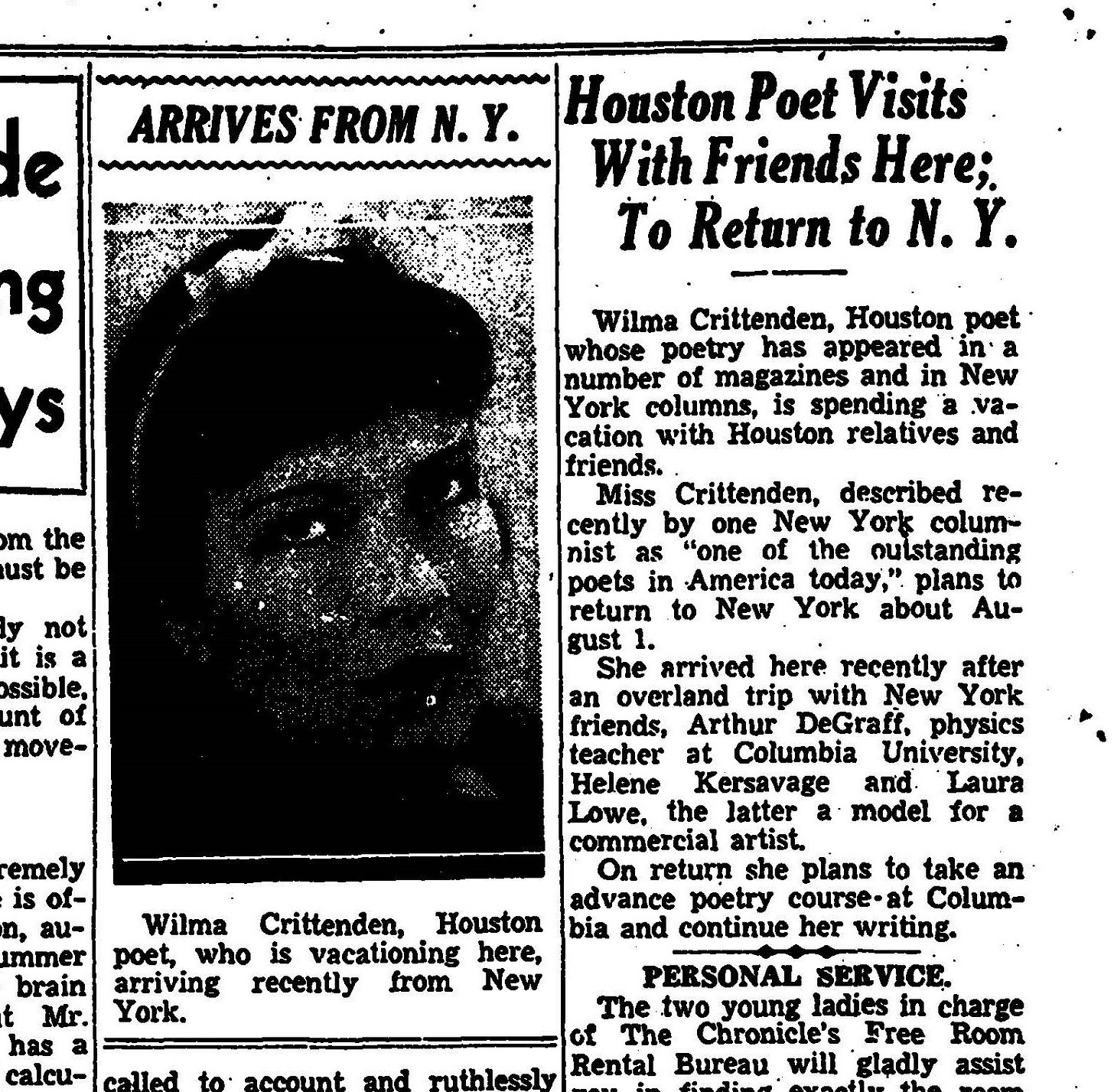

First among them, the impetuous, exuberant Wilma – daughter of the Houston Heights, poet, girl about town in the Big Apple demi-world, about whom a reporter of Broadway gossip had said in his column, “Wilma, the poetess, is returning to Houston because the first three men she met in N’Yawk offered her their lipsticks between lisping comments on the cut of her gown.”

Indeed she was returning to Houston, but it was circumstances, neither the lisping nor the lipstick, that moved her go back. In fact one of her own poems, “Greenwich Village,” in its concluding lines, advertised the spirit that had drawn her to the bohemian life of “the Village,” which she was bringing back to Houston with her:

And life was lean And beautiful, And love was young and glad – It’s good to be A Village poet And a little mad.

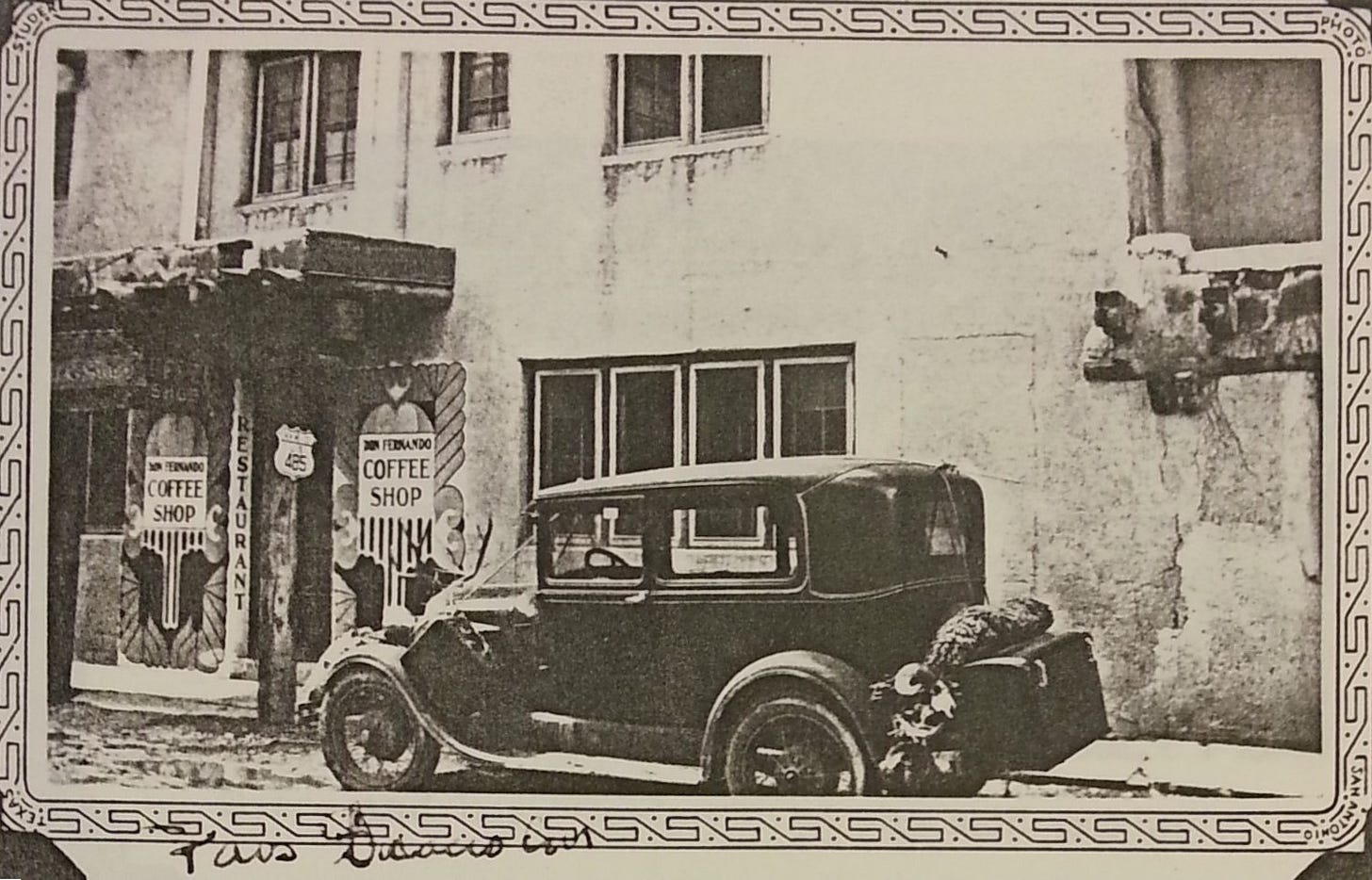

I’d met her in my own about-towning, in the company of Parker Tyler and Charles Henri Ford, two other Southern boys storming the City – Charles had even lived in San Antonio for a time, in his younger days. The two were famous – infamous, some would say – for their portrayal of that very New York demi-world, a queer world, in their co-written novel, The Young and Evil, so scandalous, which is to say, so truthful, that it could not even be published in New York, had to flee to Paris to see print – where Charles followed, and where he – small world – became the “special friend” of Tchelitchew, the Pavel I’d known myself years before (though not, myself, as quite such a “special” friend).

Wilma and Parker had become their own special friends – she even had stars in her eyes for him. Too bad for her, since the stars in his own eyes walked elsewhere, and in trousers – or perhaps I should say to be clearer, less coy, now that Deitrich and other women were already making trousers their own by then – the stars in Parker’s eyes were for men. So it was not that that prompted Wilma to buy her ticket to Houston; perhaps it was something of the weariness I’d come to feel myself.

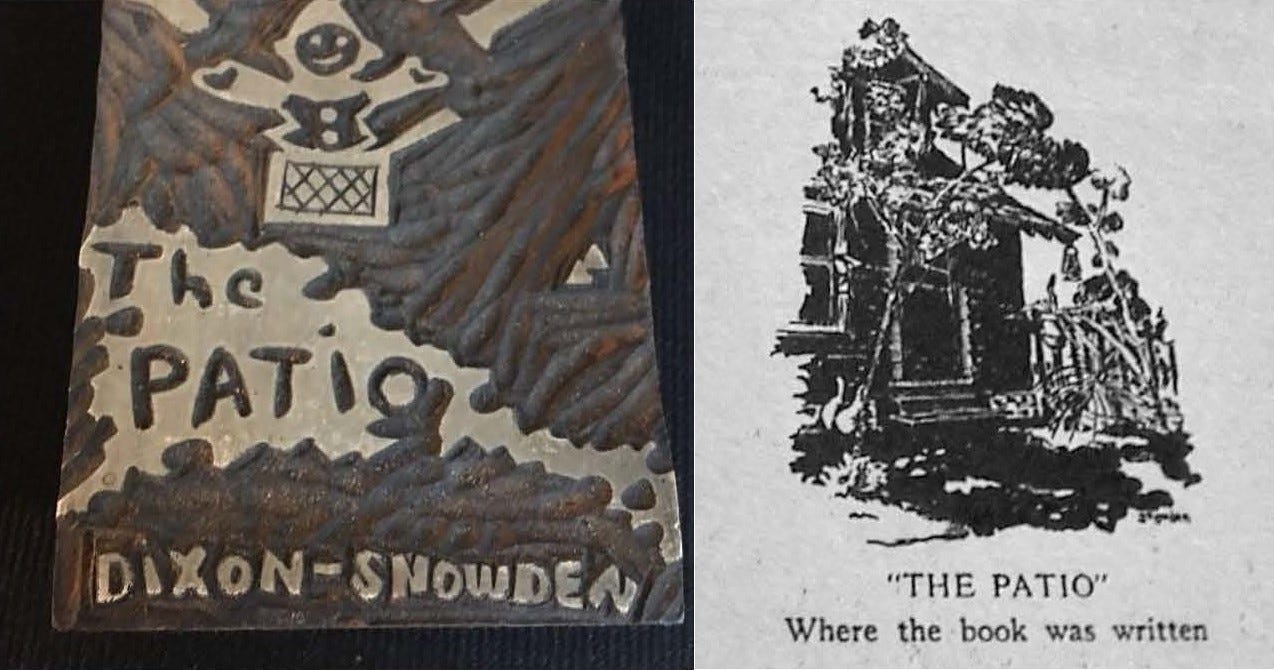

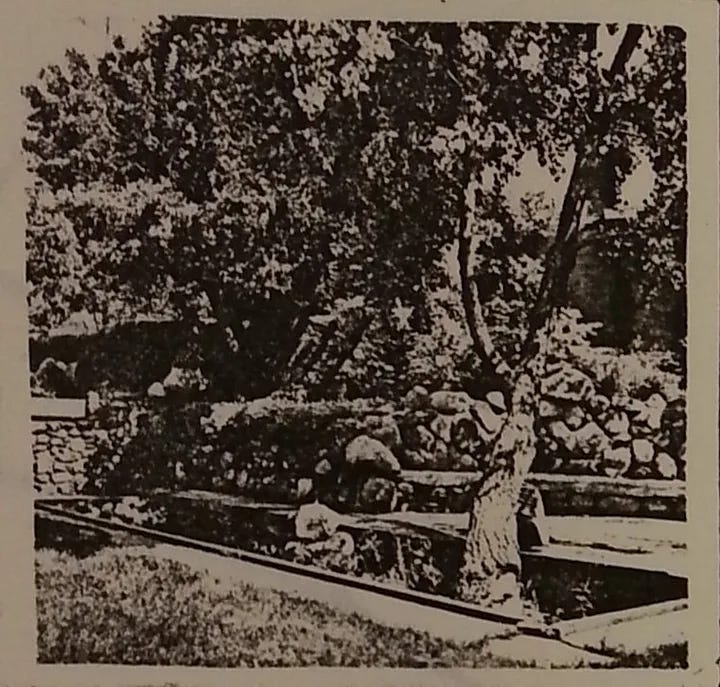

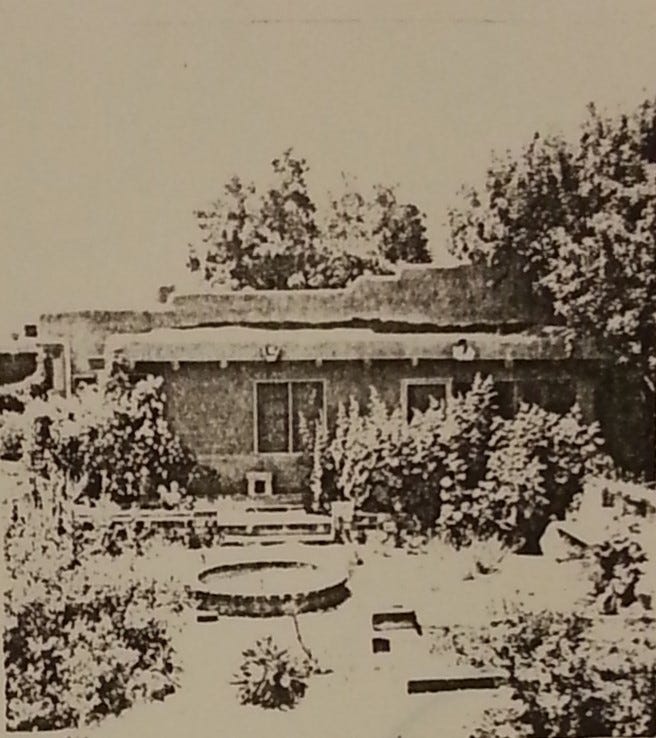

And then there were Royal and Chester, another couple of Texans who’d come to New York to meet, as it happened, and now that they had, were decamping back to the Gulf. Royal, some years older (Chester was my own age almost exactly), was becoming rather famous as a nature writer, story teller and lecturer. They had met when a publisher hired Chester, a young artist, to draw the illustrations to one of Royal’s books. They formed a partnership that went beyond books and publishing, and had already returned to Houston, to the “Patio,” their shared residence/studio on Truxillo Street, Chester painting in the main house, Royal writing in his study out back. They hosted gatherings – their “vespers,” as they called them – of Houston literati, which might have been called salons in more sophisticated settings – settings with running water and electricity. But the rustic life, meaning the life of the mind and eye, and a life together, seemed enough for them.

I knew them well enough in New York to stay in touch – though to tell the truth, they held some ideas, metaphysical almost, which I smiled at, and found difficult to take seriously. But they were both lovely men, and so when I returned to Houston I knocked on their door almost before I’d unpacked my trunk, and I became a regular at their amusing soirées.

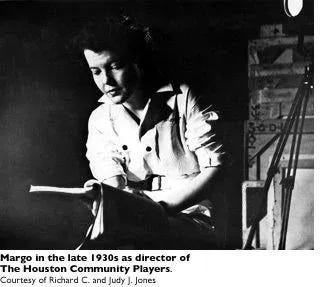

One of the most amusing people I met there was Margo – Margaret at birth, but “Margo” as she’d christened herself, and she withered with a glance and a tart word any who dared to use that other name. Though “amusing” is such a pale descriptor for such a force as she. In the summer, she’d stage-managed the Houston Federal Theatre production of Chester’s play, Pioneer Texas. How quaint: he was a better artist than he was a playwright by far – but bills had to be paid. Margo’s theatre dreams went far beyond stage managing. One day she would have a theatre of her own, she proclaimed, and one day she would direct on Broadway. Even as one who knew the New York theatre, and whose Broadway dreams had paled in their own way over the years, I could almost believe hers would come true. Even now she, and her friend, aspiring playwright Zoe, were away at the Moscow Art Theatre Festival, in the company of New York critic Brooks Atkinson, playwright Lilian Hellman, and Al Hirschfeld, theatre world caricaturist – though how welcoming those Broadway luminaries might have been to a pair of brash young women (still girls, almost) from Texas – almost as far from New York as Moscow, and more exotic – who could know.

Through Margo a queer Houston world had begun to open for me, a world of theatre and art and writing, and of queer vibrancy, that I could hardly have imagined possible along the banks of sluggish Buffalo Bayou. Young actors and artists and writers and hangers-on, who could not resist – had no desire to resist – when Margo called them to join her quest to “integrate all the arts,” which meant, when she said it, direct all the arts toward fulfilling her own theatre dreams. Because for Margo, life was theatre and theatre was life, absorbing everything and everyone.

I could only be grateful that this tribe of youngsters, most 10 years my juniors at least, seemed inclined to include me as one of their number. How lucky that, as Mrs. Cherry noted, I at least appeared to be younger than my age. They might not have been so welcoming of a man as old as I who showed in his face the years (and wisdom) he’d acquired. Because wisdom, and a wrinkled face, often do not rank high among the young.

Margo had even talked with me about writing a play for her, that she could use to found her theatre company when she returned from Moscow. And I had begun to outline one I thought (hoped) might appeal to her. How disconcerting, I sometimes thought, for one as mature as I to be wondering if I’d meet the expectations of a young woman of no real record in the field in which I’d toiled for a decade already. I almost regretted saying I’d do it, but even if you resisted at first, eventually you gave in, because “you couldn’t do anything else,” as Cardy, one of the young artist set said, as we commiserated over a drink one evening after Margo had had her way with both of us. She larded her cajoling with “darlins” and “babies” and “sweeties”, but you knew you wasted your time demurring, because she had a way of making sure that she achieved her objectives eventually. And so you went along, and in the end were glad you did.

Part 4: Dance

Some of my New York friends who still wrote gasped in amazement at my return to Houston. Not many did still write, and even those few would likely fade away in time, since the “friendships” had been built mostly on late nights on the town and gallons of bootleg hooch. But the few who still did write wondered what I could possibly find to do there. Or who. As per one, who reveled in his to-the-limit incautiousness – who delighted in claiming that he was a model for Ford and Tyler in their Young and Evil. I could see the mock-regal turn of his head and hear the lisp from his pursed lips as I read his words: “My Dear, how ever do you keep your sanity – or is that sin-ity (I blush!)?”

Often, the wonder came from those who came themselves from small towns in Ohio or Nebraska or other equally far away states from which they had fled, never, they hoped, to return. They clung to the anonymous freedom of New York with the desperation, the terror, of creatures holding on for dear life – even when the price of the life could itself be dear. And so, when one of their tribe – in this case, me – actually did return to his awful place of origin, they felt a new terror, as though the talons of their own awful places might reach out for them. I wondered how many of them would one day go back, as I had, whether by choice or necessity. I hoped that all who did would find ways not to regret it. But likely I would never know, because the letters would likely have stopped by then.

Sometimes the letters came with news of some of whom I would as lief not be reminded. Sometimes they took me back to memories of lost loves and heartaches past – which, even with time and distance, might not have yet fully passed. But a tear in the corner of the eye is sometimes not a completely awful thing, and so I welcomed the letters while they still came, and sometimes even wrote back with news of my new life – and what I was finding to do to make it livable. Perhaps my news would comfort them when their own day to return arrived.

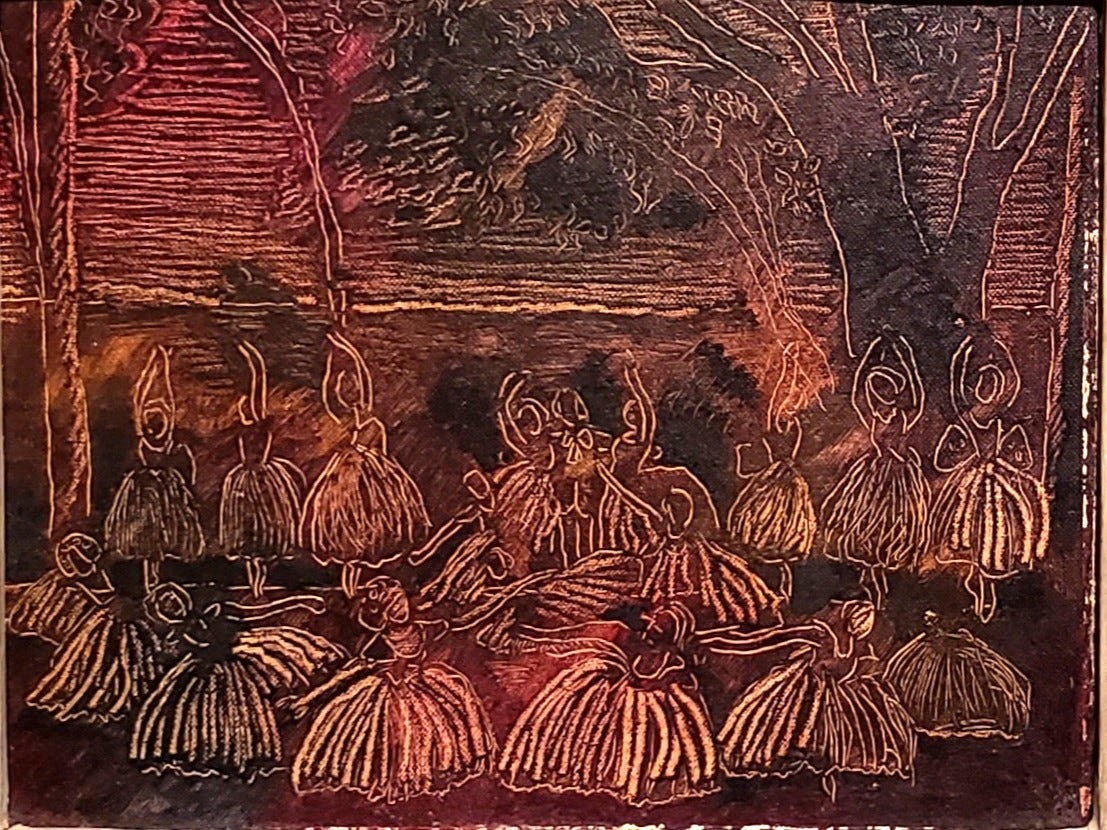

And one of the things I found to make my life livable, even in far-off Houston on the far-off Gulf Coast, was dance. By dance, I do not mean the Lindy Hop, or the Swing, or the Shag, or whatever names such popular revels might be called. Though I might, at times, with enough of the no longer prohibited hooch, attempt those myself. The dance I mean was the Ballet. For, perhaps surprisingly, Houston had long had a history with ballet, which, by the time I returned was becoming even closer. Now, the Ballet Russe made annual tours to our southern city – in the winter, when we were mild and other stops on their list were frigid.

But my ballet mania went further back. Certainly, my taste for it had grown stronger in Paris, with Diaghilev and Ballet Russes at their height, unsettling the world as Nijinsky and others danced to the music of Stravinsky and Satie, costumed by Bakst and Delauney, in settings by Picasso and Cocteau. Diaghilev was now dead, after a life of hard living and exhausting art, and the company that now came to Houston only bore a similar name. But I remembered when Diaghilev had come to Houston in 1916, or at least his Ballet had, with the great Nijinsky himself topping the list of dancers; and, even earlier, when the “incomparable” Anna Pavlova had come in 1911, partnered by Mikail Mordkin, in an astounding first for the city, and for me.

The same Mordkin who came again later, with his own company, and to whom my Houston friend Eugene, wrote his paean in poetry, and published it in the local paper:

My Love, The Dancer, Is like a horse! A young horse that prances, When he dances Up and down the stage of life. His smooth and nude and shining body, His tightly-rounded arms And legs and hips and thighs, All are shot with lightnings From a hundred thousand skies … Enraged, My Love, the dancer, Prances, prances, prances! Dances, dances, dances; Up and down the wave-licked shore. Till his rage can be withheld no more! Snorting, snarling, roaring, He plunges into the snarling sea, Determined to down it And all its strange myster[y]. …

Strong stuff, scandalizing many, no doubt, when they came across it in their morning Post, but stirring deep yearnings in others, including me when I read it in Houston in 1926, even after the hedonistic Paris I’d recently left behind.

Those earlier encounters had sealed my fate as one addicted to the drug of dance. Now, however, dance even more thrilling than the ballet of Nijinsky, Pavlova and the Mordkin who had so moved Eugene, was coming: Ted Shawn and his all male company. Called by some “modern” dance – though what could be more modern than The Right of Spring had been in it’s day? I’d had a taste of this “modern” dance in New York – and of Shawn, when I’d seen him dance his ethnic dances in programs with his wife in their Denishawn phase. But the very thought of a company composed entirely of men, and men likely minimally costumed with the license the modern-ness of the dance seem to give, revealing “smooth and nude and shining” bodies – male bodies – thrilled in ways that paled even my recollections of Nijinsky in his prime.

I’d bought my ticket the instant I’d heard the news, or as soon, that is, as I could get to the ticket office of Edna Saunders, Houston’s impresario, at Levy Brothers department store on Main. I was not the first in line. I saw many familiar faces eager to get their tickets too – many faces of young Houston men I recognized, even if I didn’t know their names. We all knew it would be an evening we’d long remember – and perhaps, dream about.

Part 5: The Evening Arrives

The actual evening, when it arrived, in February 1937, was a lovely one. The performance would be in the City Auditorium, where I had spent so many stirring evenings – including that one in 1916 when I’d first seen Nijinsky’s magic. This one, I knew, would be as magical, as moving.

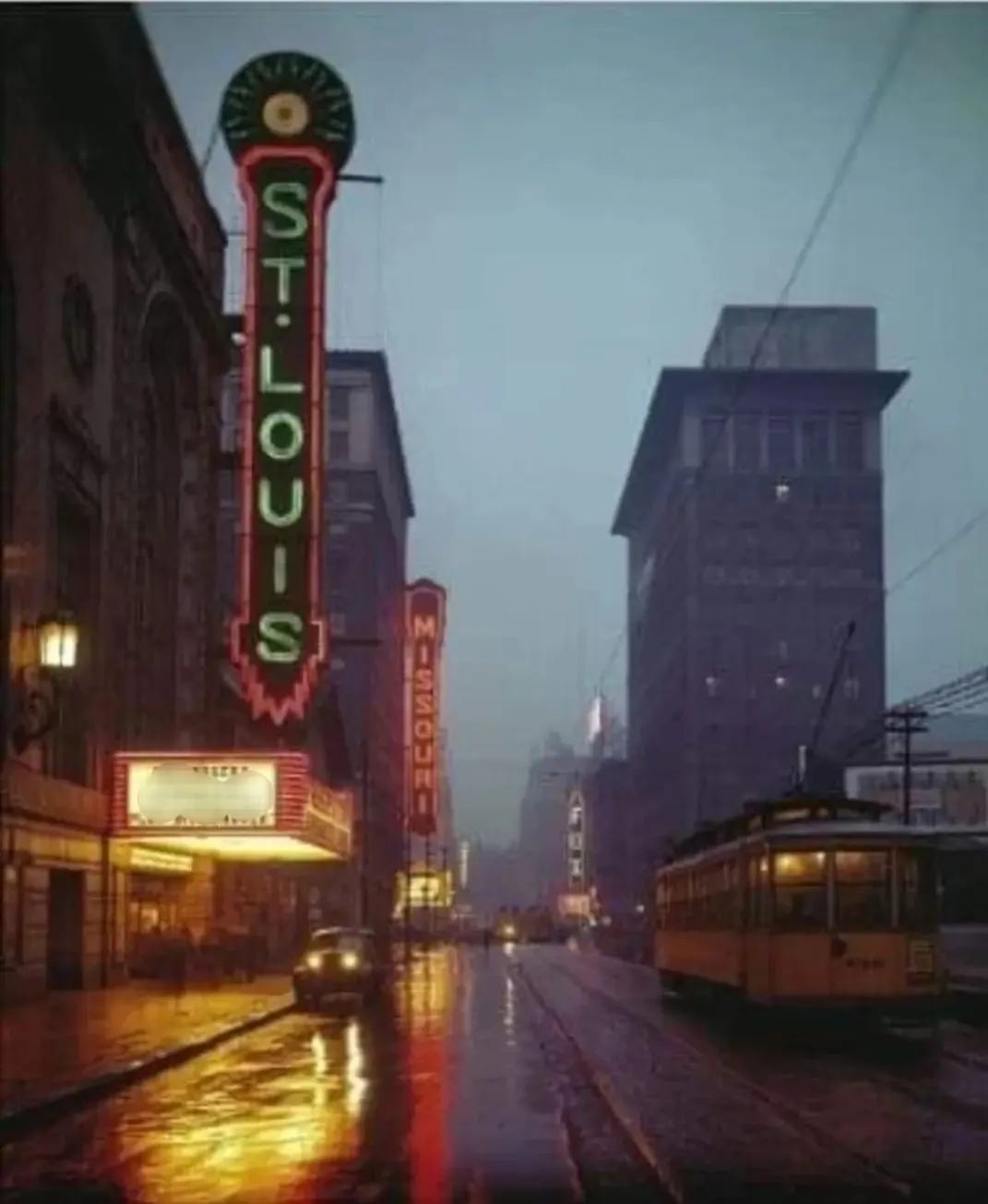

I walked from my house to the Auditorium, through the still bustling business district, the mildness of the Gulf Coast winter making the evening a magical dream, certainly as against some of the hard winters I’d known in New York. It was the southern mildness that brought the Ballet Russe to Houston so often in the winter months, when snow and ice froze the vibrancy of cities more exciting other times of year.

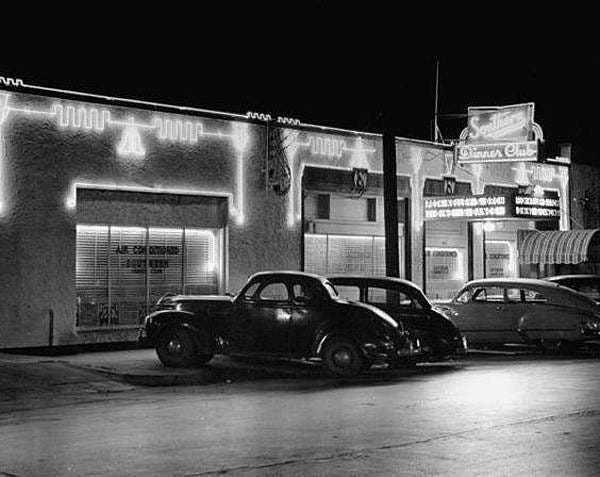

The performance would not begin until 8:15, so I decided to stop by The Rathskeller for a bit of supper. It might even be busy this evening, since so many of “the boys” would likely also be needing something before the performance, to make sure their stomachs didn’t rumble at the dramatic moments of what all anticipated as a riveting (and arousing) exposition of maleness, such as they often dreamed of, but seldom had the chance to see so openly anywhere but the gym.

I walked up Main Street, past the mirrored kiosk in front of Levy Brothers, and admired – some might have said, assessed – the handsome youth looking in the mirror as he combed his already flawlessly combed blond hair, his eyes darting back and forth like dancers themselves as he assessed the other men who passed behind him on the sidewalk. I did not recognize him – though I did recognize his “swift flash of eyes” and suspected the “love” it might offer. Perhaps he’d come to town on business or for the performance. Though even in Houston, growing fast and large, I no longer recognized everyone – not even those like me in that unspoken essential way. I didn’t have the time to stop to comb my own hair, or to check it in the mirror in case it needed combing, but I’d remember him in case I saw him another time.

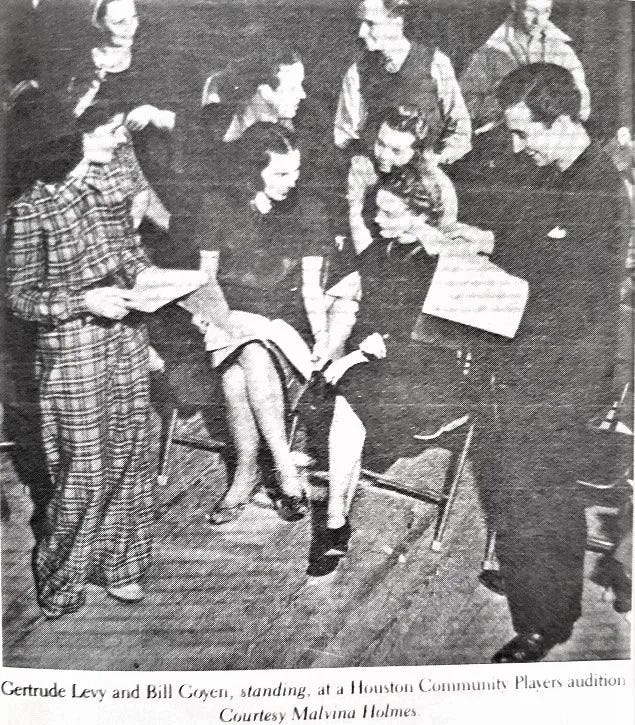

When I went through the door of the Rathskeller, I saw the young Billy Goyen, whom I’d met at Margo’s theatre, sitting at a corner table, writing, writing. Who knew if what he wrote was good – probably it wasn’t, he was still so young – but he wrote so doggedly that one day it might be good if he kept at it. Bill Hart sat at the table too, looking at Billy with love in his eyes, love which only its object seemed not to see. They both had part-time jobs at the public library, and so I saw them often, though Goyen seemed hardly to have time for an “old” man like me. But it could be he hardly had time for anyone, so absorbed did he seem to be in himself, his writing, or his shyness. Hart I’d come to know in many ways, meeting him first one evening shortly after my return from New York City, as we both stopped to check the status of our hair in Levy’s kiosk mirror.

I smiled at them and nodded, but I did not disturb them at their table, in their labors of writing (Goyen) and longing (Hart). Instead, I walked across to the bar, nodding and smiling also to the Frau proprietress, who welcomed through her door those of us who found some doors not so welcoming. I ordered my lager and sandwich, and sat alone at my table to enjoy them, as I savored the anticipation of the dance that lay ahead – and as I looked around at the other men who peopled the Rathskeller on that early February evening.

There were only men, and only men of our “peculiar” type. Like the Madame in Paris, who saw everything, but when it suited her, saw nothing, our Frau of the Rathskeller did not see – or at least pretended not to – when hands met beneath tables, or lips touched cheeks in the half-light of dimmer corners. Perhaps she really didn’t see, or wasn’t bothered, so long as the police weren’t bothered either; or perhaps she enjoyed her occasional dances with the “boys,” who could not dance with each other, not even when they’d passed through her welcoming door. That would have bothered the police indeed, at least when it suited them or their politician bosses to be bothered by it.

As in every city of any size, and likely in many towns large and small as well, places like the Rathskeller existed, places where men could meet each other, men of our “peculiar” type. Where there’s a will there’s a way, and a place, and our will to meet each other found its way everywhere. Even here in Houston, just blocks away, we’d found more places: The Old Vienna, the Capitol Bar, Rex’s. And the kiosk at Levy’s. And what some might consider more unsavory places: the facilities in the basement of the Milby Hotel, Sam Houston Park, across from the Central Library, the blocks of Main Street where one could go “window shopping,” the steam rooms of the Turkish baths around the city, at midnights and mid-afternoons, and the corners of the Rice and Texas Hotels – especially the latter, where many of the theatrical types stayed on their brief stops in town, for one night stands (in double senses) as their companies made their tours.

Even as I thought of myself as a sophisticate, one who had explored (or at least heard tales of) the nether worlds of Paris and New York, I found some of “our” places unsavory myself, and knew of them only because I’d heard tales. Still, I would not condemn those who frequented even such places, since the world allowed us such few. I might not choose them for myself, but how could I deny them to others, who might not have even the meager opportunities my affluence, education and experience afforded?

As I finished my early meal (I expected I’d be having a supper somewhere later, unless the dancers left me too thrilled to eat), I thanked silently the greater powers that had granted me those advantages, which now were taking me to an encounter with art and maleness such as I could not even have imagined in the days of longing I still so vividly remembered from my youth. My only regret this night was that I would be going to it alone. Though not absolutely alone, since I knew the seats would be filled by many others like me in our essential way. Strength in numbers when the number was hundreds, almost as empowering as when the number was two.

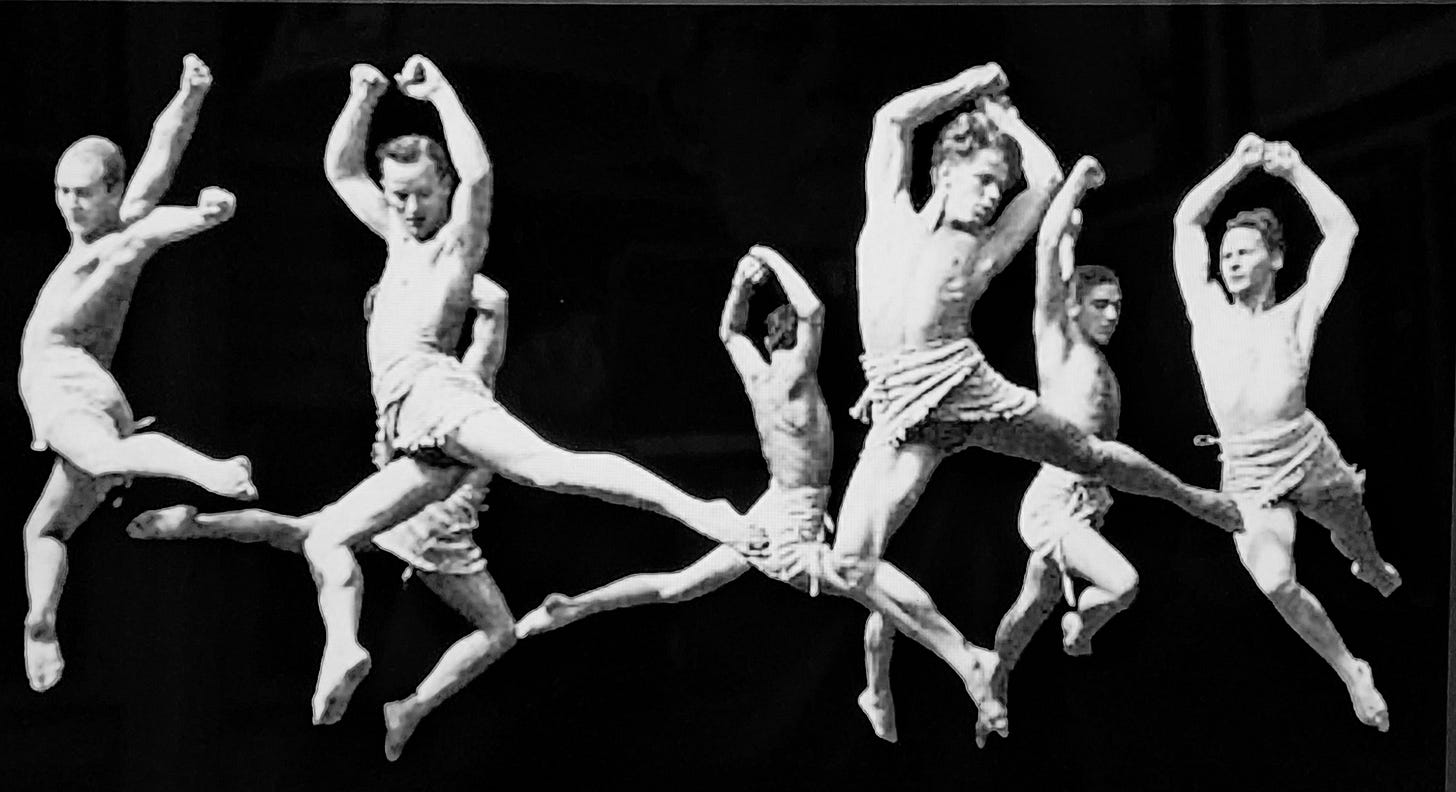

Part 6: Ted’s Men

The instant the curtain fell on the final dance of the program, the auditorium thundered with applause. Bravos rang through the air, and most in the audience – disproportionately men, of all ages, in ones and twos and groups – leapt to their feet. It was not so large an audience as the several thousand who had applauded the femininely classic Ballet Russe that I saw in the same space the month before, perhaps, but this night the several hundred on hand (and now on their feet) cheered Ted Shawn and his young men dancers with a masculine abandon that thrilled the heart of even an old jade like me. Not so old, really, but sometimes feeling so.

But not so this night. What I had just seen on stage sent bolts of youth and life through me, and even I, who scoffed at standing ovations except when the very pinnacles of perfection had been reached, found myself on my feet with all the others. I began to think of the praises I would sing in the review of the performance I had agreed to write for the newspaper: “America interpreted in dance … with the program Shawn and his eight personable youths gave Thursday night … the strength of all men dancers … perfection of grace, rhythm, balance and muscular coordination … young, of slight build, buoyantly graceful … the epitome of eager, young America … applause often wild at times …”

Shawn and his beautiful young men returned to the stage time after time, sweat still glistening on their lithe, near naked bodies, holding hands and taking their bows before the adoring crowd. The rush of virile images almost intoxicated.

At last, when the dancers had taken a final bow, the harsh lights of the auditorium came up, telling us beguiled witnesses of their masculine magic that the moment had ended, that the time had come to return to a world not so impossibly perfect as the one we had just lived in for two precious hours, in the company of eight seemingly flawless youths, and their genius master.

As we all walked out of the rows, and up the aisles, and out of the doors of the auditorium, I spotted some familiar faces among the many unfamiliar ones; spoke the occasional “Good evening,” “How are you,” “Splendid” – though I hardly wanted to speak at all for fear casual pleasantries, or even exclamations of wonder, would hasten the flight from that other realm the dance had taken us to, fear that I would be brought back to earth – too soon!

Across the way I saw an august gentleman I had not seen in years. Memories came back, of touches from his hands years ago. Not unwelcome memories of not unwelcome touches. When I was just man enough to shave, but already fully man enough to respond, to welcome the touches even though they surprised at first and frightened a little. Respond willingly, happily, thrillingly.

I had not seen him in decades and might not even have recognized him – time had made such changes in us both – until our eyes met and took us both back to those past times for an instant. Or so they took me back, and I assumed, hoped, they took him back too, to those touches touched so many years before. His eyes, which lingered a long moment looking at me seemed to say so. Then we each went our own ways, he with a young man holding his arm, steadying his slow walk up the aisle.

Once outside, in the crisp February night air, I knew that the precious feelings from the precious respite would fade soon, and I breathed a sigh of resignation – but vowed to myself to keep the images and the feelings alive in memory.

For a few moments I walked behind Billy Goyen and Bill Hart, on the way to their streetcar. The two had watched the dance together, from the highest, cheapest seats. I heard Goyen gushing, as gifted, slightly priggish young novices will: “I received one of the greatest inspirations I have ever felt when I saw the Shawn dancers.” I might smile at his full-of-self histrionics before his adoring friend, but I could not disagree with the truth of what he said. I too had received inspiration which not even my worldly wisdom could muffle, at least for the little while that the lingering euphoria lasted.

At a corner the boys turned and hurried up the dimly lit street to catch the car already slowing at the stop. Young men, actually, not boys, but 15 years my junior, so how could I not think of them as “boys?” I turned the other direction, toward Kelley’s Grill and a late solitary supper, thinking of the evening that was passing so quickly. At least the lights would be bright in Kelley’s, the champagne chilled and the chatter from other late diners lively, and no one but I would notice – or care if they did – that I ate alone in my booth.

After my meal I walked slowly down Main Street, past the movie palaces whose marquees had now gone dark, past the shop windows whose displays of home furnishings and latest fashions held no interest for me, past Levy’s with it’s mirrored kiosk. I glanced, of course, to see if my hair now needed combing. Habits of long-standing will out, no matter the mood or the hour. And a young man standing at the kiosk, comb in hand, glanced back.

Was he the young man from earlier? Perhaps, though I could not be sure, so many young men had danced before me since I passed the kiosk earlier. Unlikely to be the same young man, so many hours later. But maybe; why not? Here I was again myself, not quite the same, for all those young men who had danced, but not so very different, it would seem, when it came time for these late-night glances.

I thought of going closer. Thought of casual comments about the weather and the hour, of lights for cigarettes and directions to places neither intended going. It would be a dance of sorts itself, one danced so many times before. And I thought of the dance (of sorts) that might be danced later, in a room at the Texas Hotel, or my bedroom, childhood bedroom, overlooking the garden of my house. It might not rise to the level of that danced by Shawn’s young men, but it would be my dance – mine and his. Perhaps he’d seen Shawn’s men too, and felt the same inspiration that I felt, and the two Billys, and the five hundred others, at least, who had seen them with us. And even if our dance fell short of the art we’d seen, been inspired by, longed for, it would be ours. Before the dance begins, the possibility of perfection always woos. And I had been won by the temptation many times before, in Houston and New York and Paris – and other places.

And yet this night, even as I longed to know, to feel, something of the paradise that Shawn and his men, through their bodies and their steps, said could be, I was not won over, I did not go closer, I did not begin that “sort of” dance, which might, or might not, be a fitting coda to such an amazing evening.

The chance of “might not” loomed too large to take the chance of spoiling what had been so magnificent. Even though memories of nights with Clem, with my Cellist, with some (few) in New York, and even one or two in Houston, enticed with the possibility – possibility of something splendid – realized …

But there had also been other nights, many, of possibility dulled by the real … And so this night I would not take the chance; I would not tempt fate (as I was being tempted) in the hope that I might thus hold on to that respite from a harsh world – harsh for men like me – that this night had said might – might – be a possibility. I walked on along Main Street and across downtown to my dark house in Quality Hill and a lonely bed, sublime, for this night at least, in loneliness.

Part 7: Gay Russian Style

“My father – step-father, really – is a cellist.”

How my heart pounded when I heard that word – Cellist – from across the room.

“You’ve probably heard him play, with the symphony or the Josephine Boudreaux Quartet. He’s really quite good. English by birth, but he’s been in America forever. Married my mother after we came to Houston when I was a child. I took his name, though frankly I’ve had some second thoughts, now that I’m older – and now that he’s bugging me about certain things which shall remain nameless. If he keeps it up, one day I may go back to my birth name, Rafalsky – though my mother had shortened that to Ralph by the time we got to Houston. Rafalsky might have been too much for southern flowers, girls or boys, to deal with back then. I know all this is sometimes almost more than I can deal with myself.”

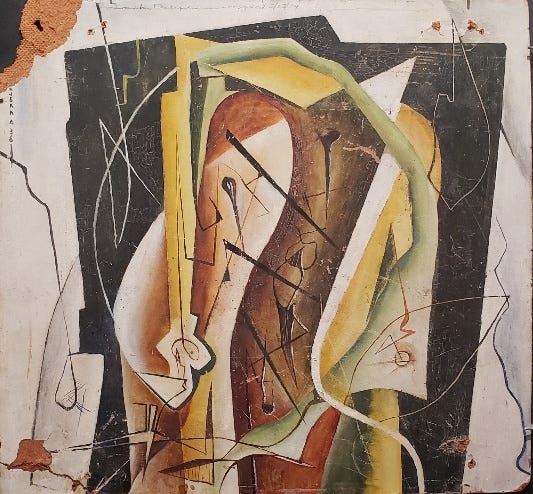

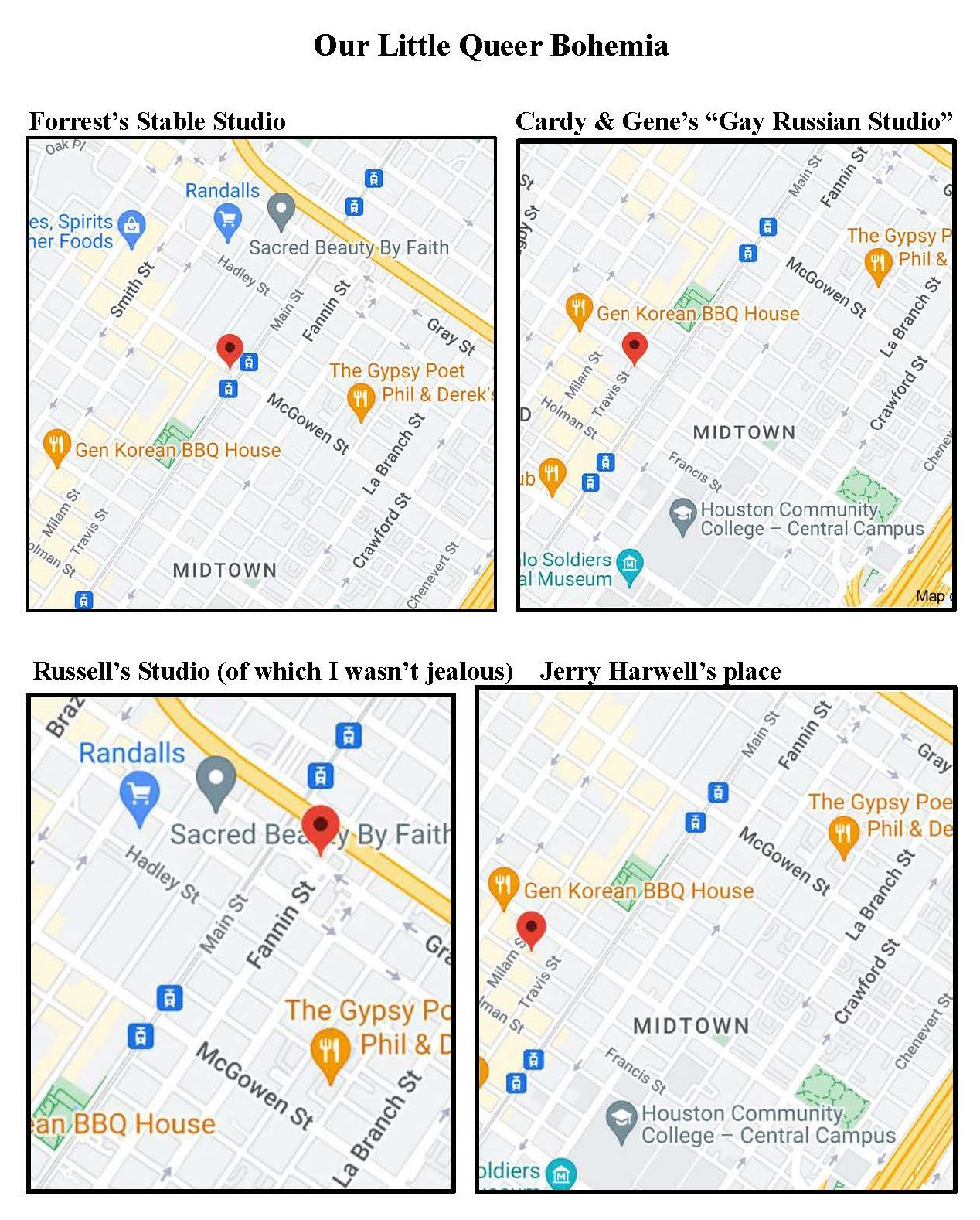

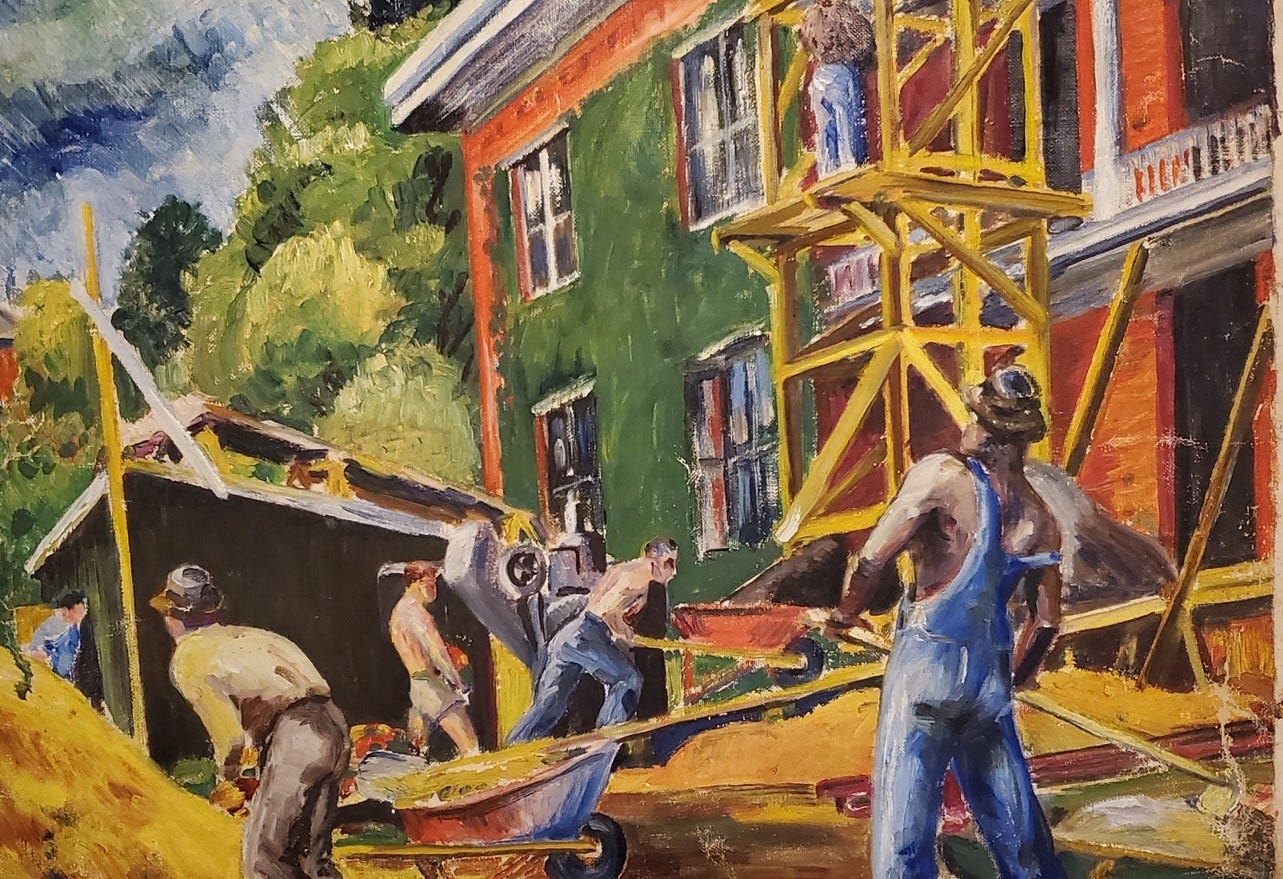

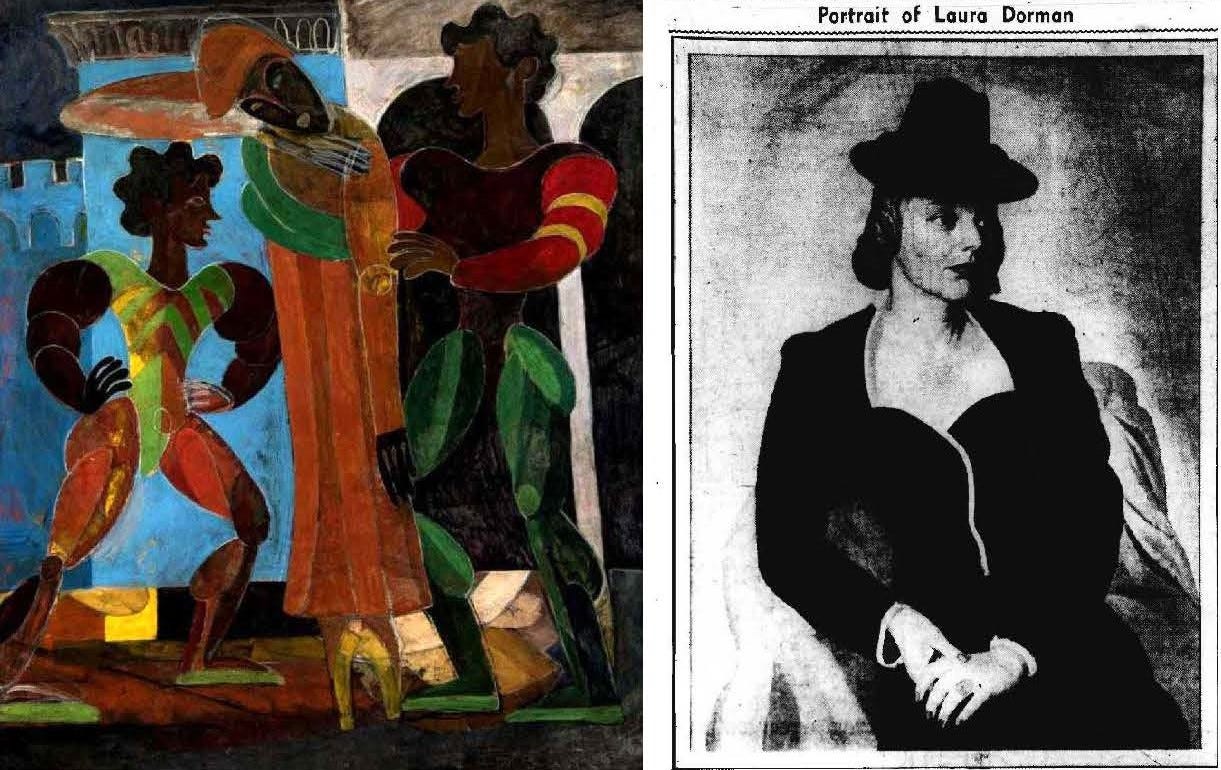

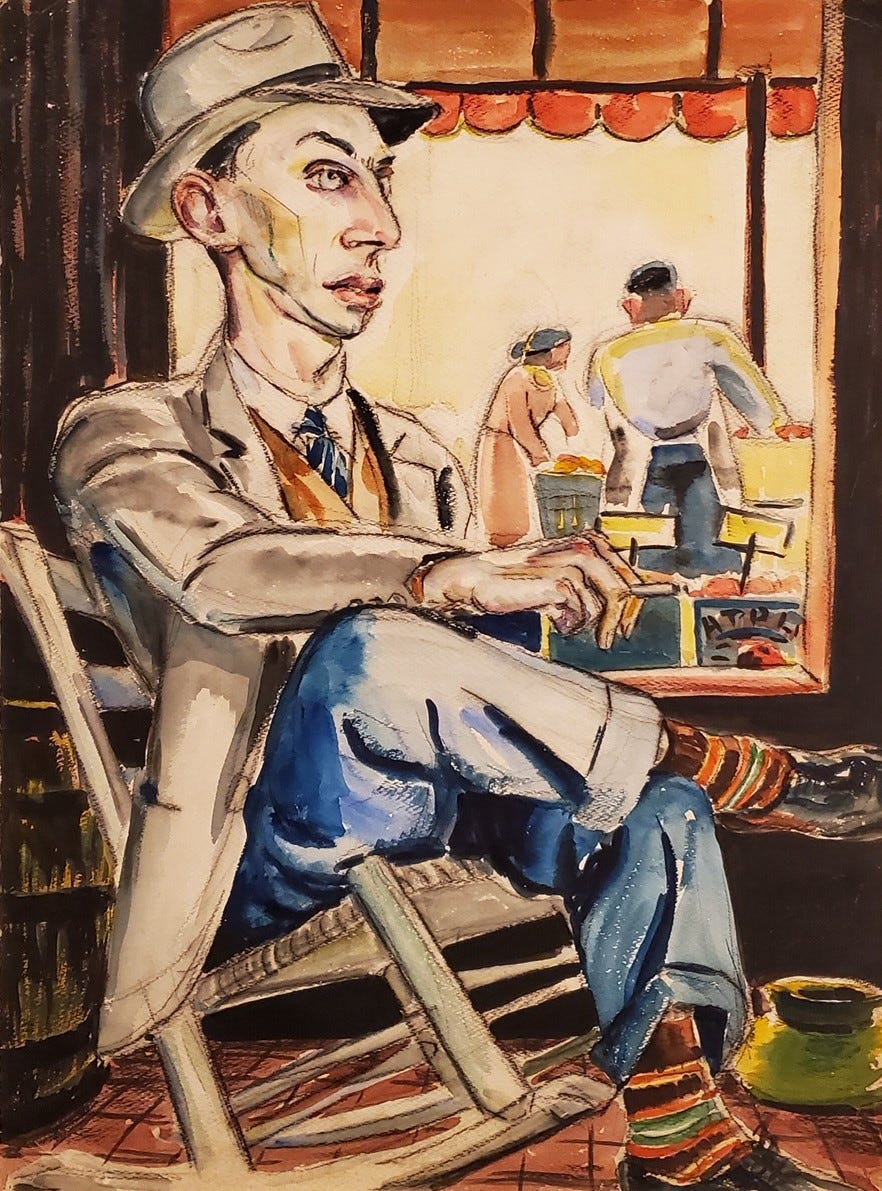

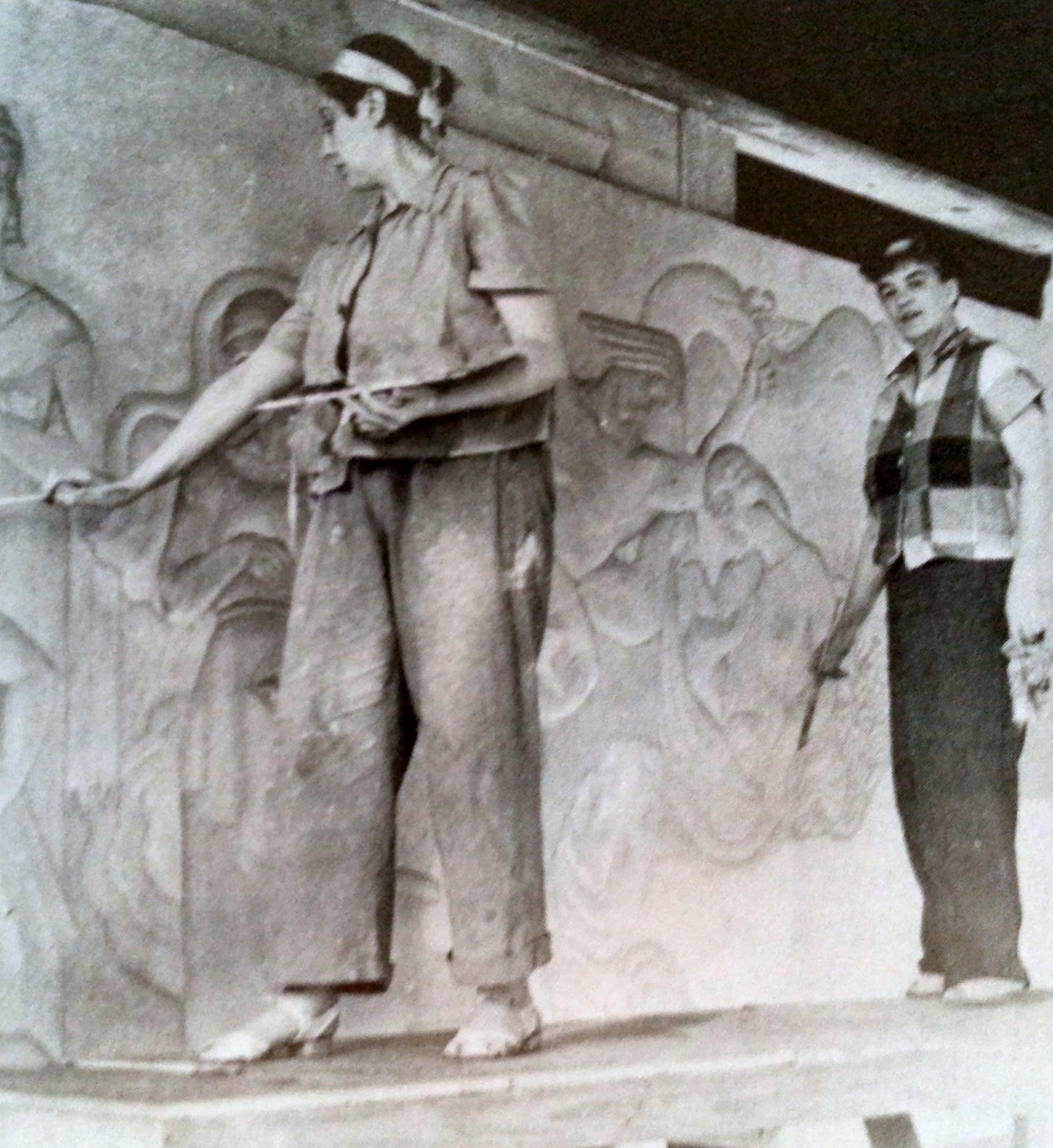

The speaker was the young – not quite so young as Goyen and Hart, but 10 years my junior, so still young in my book – talented painter and theater designer, Gene Charlton. The scene, the house at 3211 Travis Street that he shared with his partner, Carden Bailey, himself a painter of society portraits, especially of the children of privilege, in which genre he had become the Houston go-to choice. Charlton himself painted more interesting things, verging on radical in fact, and with a spark of genius some might think surprising from such an art byway as Houston, way down south on the gulf coast. Perhaps it was that “partnership” that Charlton’s step-father felt the need to bug his step-son about.

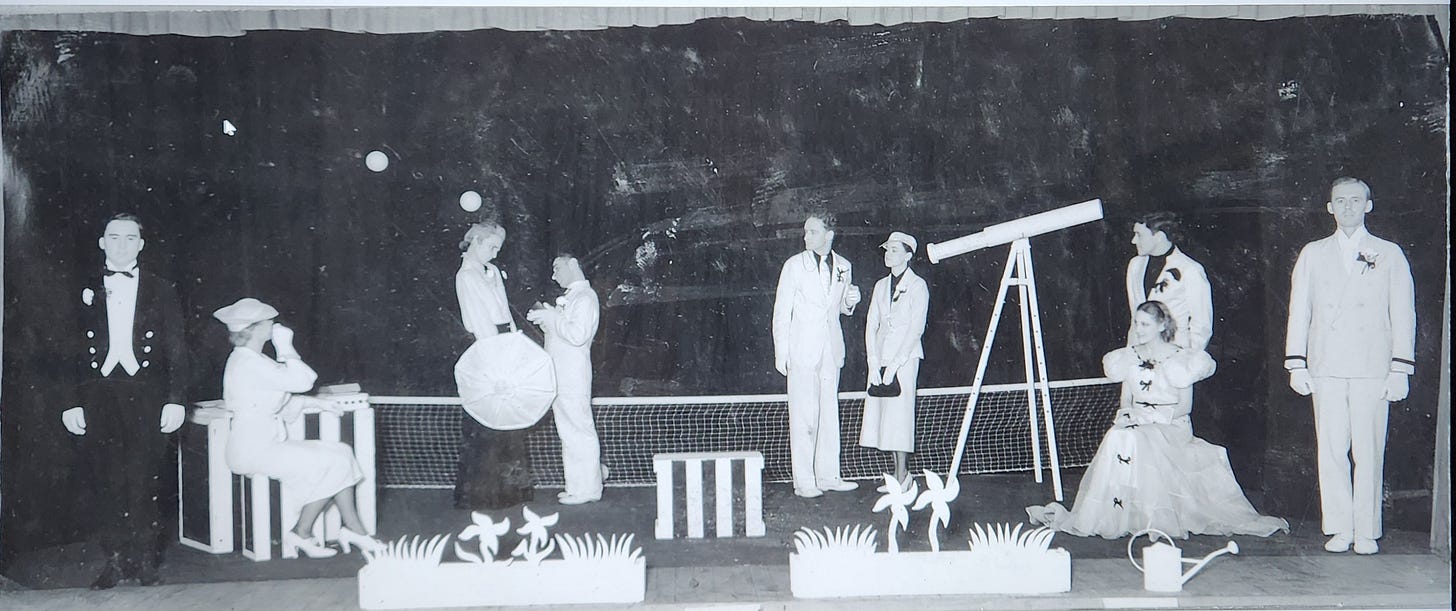

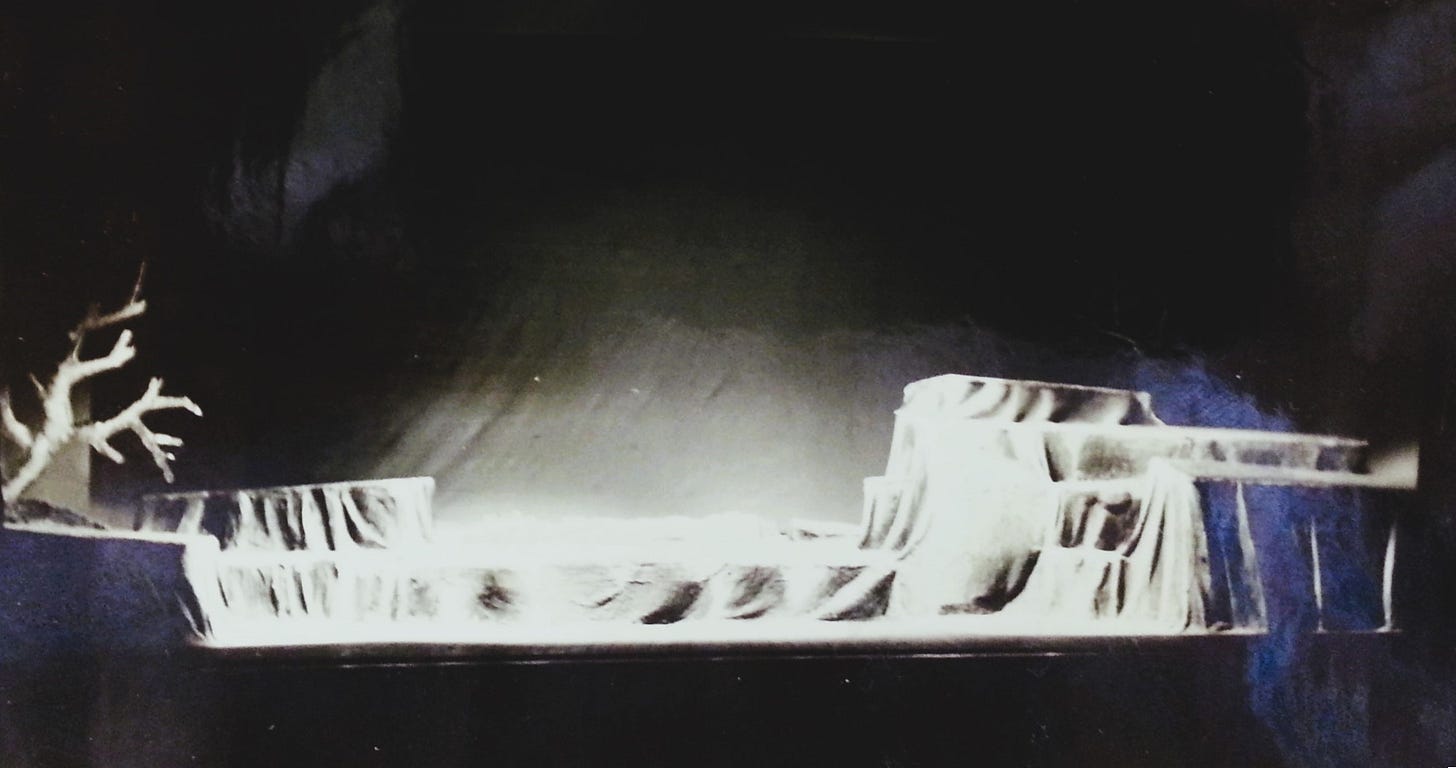

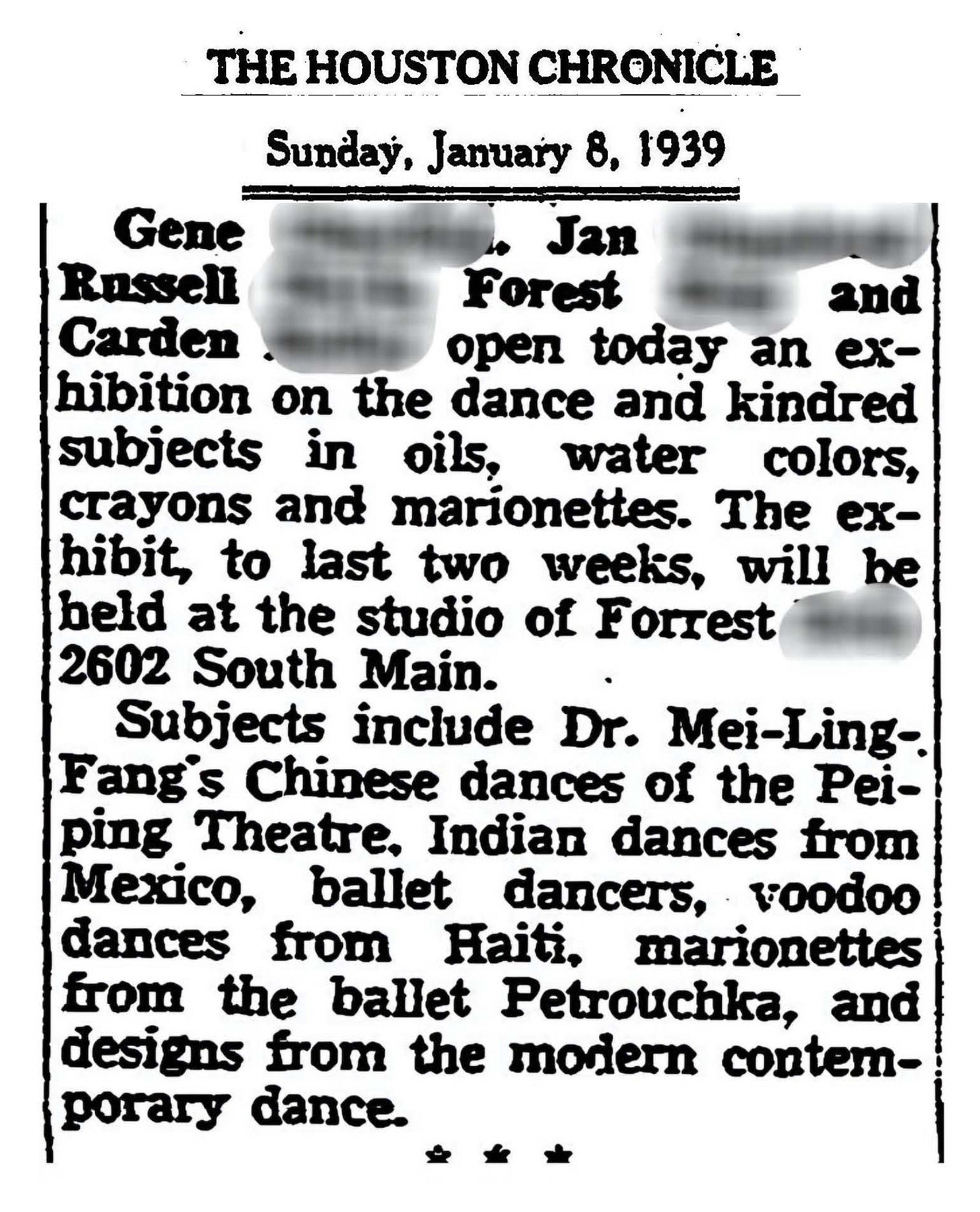

I’d met Gene and Carden through Margo Jones. She’d “convinced” them to design sets for her Community Players theatre productions. First, for The Importance of Being Ernest, they’d created a splendid black and white silhouette setting perfect for the Wilde satire; and now, for the last production of the season, a black and orange room in a Moscow tenement, which set just the right tone for Katayev’s comic play about Soviet housing shortages, Squaring the Circle.

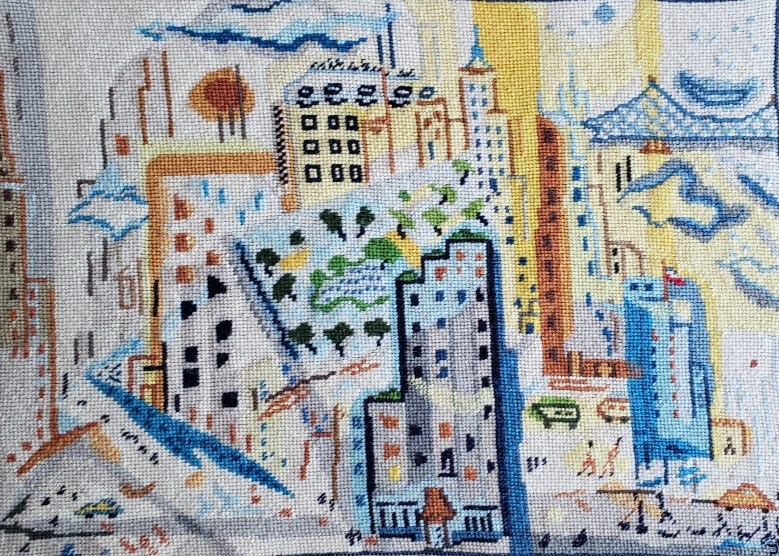

That bit of theatrical flourish no doubt inspired them to recreate their own setting in a “Gay Russian Style,” as their newspaper arts editor friend, Ione, wrote with a wink and a dropped hairpin, “painted a dazzling white … trim turquoise blue banded with deep green scallops … window frames outlined in deep blue and doors in vivid scarlet … yellow dots in the middle of each green scallop.” GAY Russian style indeed! Many of us caught the wink and shared the smile.

And I smiled, looking around the room on this festive May evening, when many of the more talented, and some of the more outré members of the small, but lively, Houston arts community had gathered to pass a couple of recherché hours pretending to be only who we wanted to pretend to be. There weren’t so many places anywhere that we found that possible, but there were some, even here in Houston.

“Baby, you have such burdens to bear!” The irrepressible Margo put the perfect kibosh on even the mock self-pity Gene pretended to, this evening.

“I do, I do,” he said, and he then leapt to other topics. “But Europe will lighten my burden, I’m sure. We’re going there, you know. This fall, with McNeill, for our grand tour. Taking a cargo steamer out of Corpus Christi to save funds, since we’ll be there for months and months. Paris, Florence, Venice – the grandest tour. We’ve been planning it for ages. I’m painting watercolors furiously to make money for the trip – a hundred, so far, at least. And Cardy is dashing out his penetrating portraits of Houston’s young heirs and heiresses. We’ll need buckets of cash to do things in the style to which we aspire. Thank God Cardy speaks French. All I can manage is English – and a little Polish. Rafalsky, remember.”

“Paris” and “Cellist” and “Gay” repartee combined on this May evening in Houston to take me back ten years – more than 10 years now – to that earlier time when I too was young and newly launched into a glittering world of Continental sophistication and “eternal” romance (at least in imagination). What a bittersweet pleasure, seeing other young men like me as I used to be, in youthful naiveté planning their first adventures in the BIG world, at the side of one they loved. Not that I believed deep down that I was so knowing even now, nor so stale. But that first flush of such an adventure was a feeling – an enchanting one – I’d never know again. And I felt a pang of envy at what lay ahead for them, Gene and Carden. Ah, to be young again, in Paris, and in love – with someone, and with art. Even the scent of magnolias wafting through the heavy evening Houston air could not rival such perfume as that.

I almost longed to go on the tour with them. I hadn't been back to Paris since I departed in 1926. For years I'd had no desire to go - and then no reason - and finally no interest. But now, hearing the excitement in Gene's voice as he spoke of the discoveries that lay ahead for them ... Now, the memory of Paris – the allure of Paris – caressed me and drew me close.

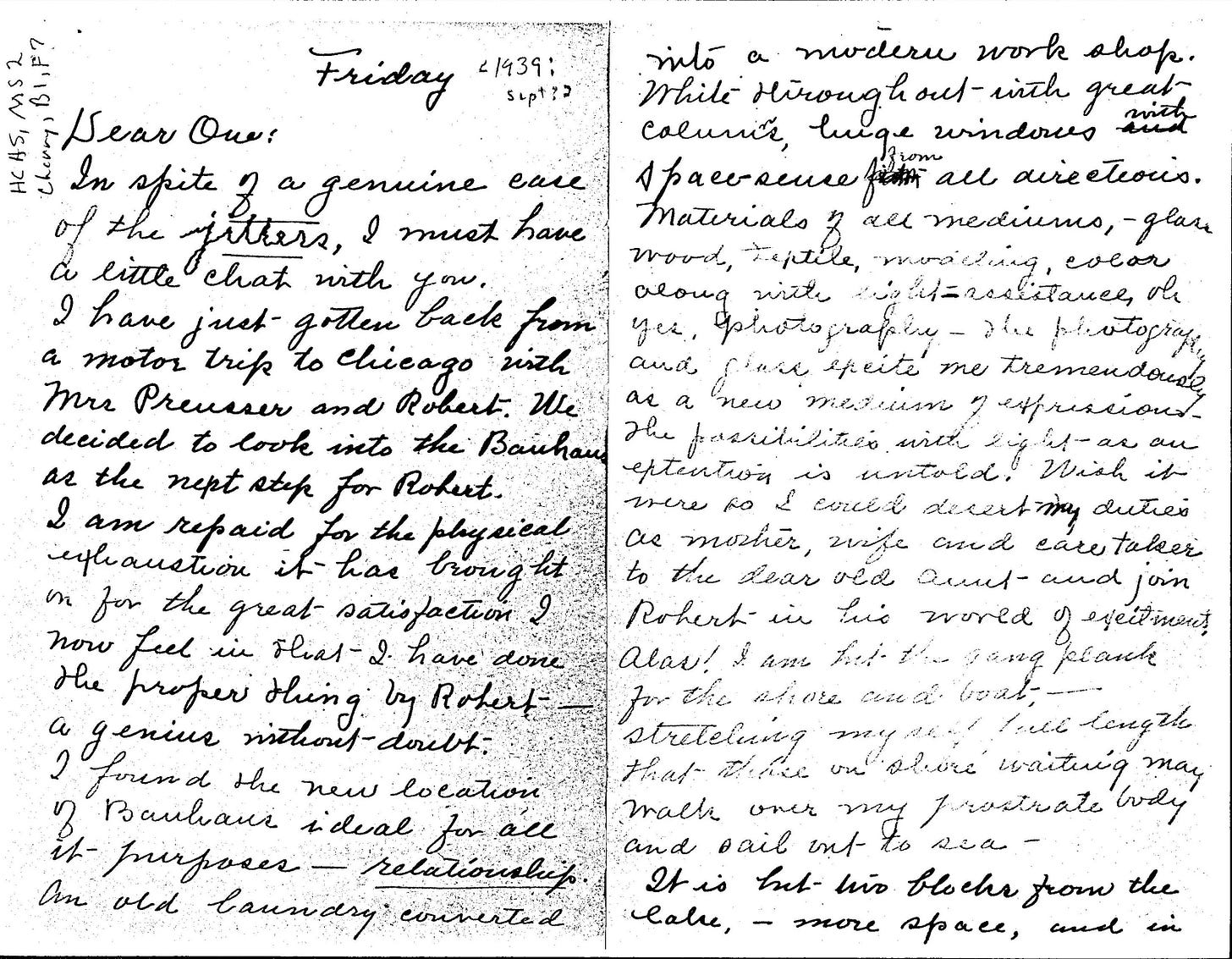

I knew the McNeill he spoke of - McNeill Davidson, like me also a former student of Mrs. Cherry, a creditable painter, and now an inspiring teacher to the most gifted and exciting young Houston painters. A woman fighting against the odds in her work, with a family of children, loved, no doubt, but demanding time, attention, energy that could have gone into creative efforts of another sort, the sort on canvas; of a husband, loving and loved, no doubt, but of an older school who tolerated eccentricities like art, only if kept in their place, and not allowed to interfere with a woman’s proper duties as mother and wife; and elder relatives, revered, no doubt, but needing more and more attention as the years transformed them from pillars of family strength (or of family frustration) into dependents themselves.

I, who no longer had such family members to love, be loved by, be dutifully attentive to, could not criticize, only empathize, with McNeill’s almost inevitable disappointment at how much she wished to accomplish in her art and how little time and energy she had to give to it. So it seemed to an observer, at any rate. Mrs. Cherry had hinted as much in her mentions of her former student, co-worker in art and dear friend.

Return to Paris! What a powerful thought, now that I thought it, for the first time in a decade, as a real possibility. Perhaps I would talk to McNeill about joining her little Paris party.

Then almost instantly I remembered a phrase I’d heard from a writer acquaintance I’d encountered in New York: “ You Can’t Go Home Again” – a phrase destined, he’d said, to be the title of his next, and greatest, novel. He’d shown me some of his manuscript, a few pages from a mountain of paper that filled the top of his desk and all the surfaces in its vicinity. He’d seemed so troubled and in such decline that I doubted the novel would ever be finished, but his title lodged in my mind and would not be forgotten – even though I had come home again myself – though only after it had become a home in place only, with none of the family fabric that makes a place HOME in the fuller sense that gives it power for us, whether we’re there in fact or not. Perhaps for me the true phrase should be, “You Can’t Go To Paris Again.” Not the Paris that once was HOME.

Though I’d grown up in Houston, and to Houston had returned, Paris seemed my real home: home to the man I had become, the man I now was, the man I would be, I hoped, for all the life I had still to live. The thought of returning there, even the idea of it, enticed and frightened me as Houston never could.

Well, something to think about, though the likelihood of my making the trip might be slight. I could, at least offer the young men my on-the-spot advice, even if now 10 years out of date: direct them to Café Gaudeamus, the Bal Musette on Montagne Sainte-Genevieve, the Madame’s garden. Perhaps give them a letter of introduction to Pavel, who might remember me; surely, at least, his new lover, Charles Henri, would know my name from our New York days. But would they want, or even listen to, the nostalgic blatherings of one so long past his prime (in their eyes, at least) when they had their own Paris to discover, to explore, for themselves.

I smiled at my conceit and walked out into the spring night. I looked back at the glittering Russian dacha in the Magnolia City, an exotic setting in which all was theater, in which all were playing parts. I heard Margo, now standing in the door, saying, between deep puffs of her cigarette, “Baby, you must come with me to Pasadena. I’ll be there all summer, at The Playhouse. It will be smashing.”

I walked up the empty street, toward the streetcar, which would take me home, an empty house, but a setting in which I could play my own part without threat of contradiction, deliver my soliloquies to myself, alone, without interruption from the eager young just starting on their exciting journeys. I wished them well, but I would not go with them. Not this time; not yet.

Part 8: Alone

So many of my evenings ended with me alone that I sometimes wondered if I wanted them to end any other way. I told myself I did, that I wanted someone beside me when the last light of the night went out. But that was not such an unattainable goal – having someone beside me – if that was what I really wanted. Compromise, tolerance, even (I blush to say it) money could see to that. So I had to admit, even to myself, that saying so I might be fooling myself (trying to anyway).

I had come to enjoy, even if I wouldn’t admit that I prized, the serenity of solitude. Or if not serenity, the simplicity of it; some might say, the selfishness of it. My mother had been heard to say that such selfishness almost certainly meant she would have no grandchildren. As though grandchildren were the birthright of all mothers who give life to sons.

She’d been right, of course: she had no grandchildren. Not by the time she died, though she’d have been right even had she lived to a ripe old age, instead of dying at a mere 70. I felt a twinge of guilt that I’d been selfish in that way. Surely she knew the reason why, though we never talked about it. Surely mothers who give life to sons must know a thing like that, whether they choose to speak it or leave it silent.

I suppose there might have been ways for me to give her the bundles of joy she so desired, even as the sort of man I was – had always been. I knew others who’d managed it for their mothers. And I suppose the mothers were pleased, though so often the men themselves, and the wives necessary to the accomplishment of the task, were not. How many of those men I knew, and the wives, even in Houston. It made me weep, almost, to think about the frustration and pain – and fear of discovery, of acknowledgement – they bore so that the mothers could dandle their bundles.

I thought of one son (and one wife) in particular as I ruminated on my selfishness in that regard. I’d known him since we’d been schoolboys together in the first decade of the century. Then we’d been best friends, so close some made comments about “the perfect couple, two bodies, one boy.” I knew to dislike the comments even though I then had no understanding why.

Our intimacy continued – grew closer, grew more intense – as we grew older. I lay awake (or half awake) night after night, tortured by a cruel agony of yearning for him, reveling in the anguish of longings unfulfilled, made bearable only by the certainty that one day exquisite fulfillment would come. I had come to expect that it would be the foundation of my future, as dreaming of it had been the foundation of my past, and was of my present.

Until, one day he told me he would be marrying.

That he would one day marry, or that I would, had not occurred to me. It seemed impossible. What could he mean? It was not so much that I was jealous, or fearful at impending loss (loss, of him, was impossible – had to be), as that I could not comprehend the words he spoke – a Greek that sounded like English, but made no more sense than the Greek I struggled to decipher in my lessons – and failed at.

And then he was gone from my life, and I knew for the first time (but not the last, of course) that the world is cruel.

I thought of him, with his curly red hair and freckled nose, and his smile that made my heart leap and then long and then ache. I thought of the “two boys, one body,” and the thought roused me even after decades. I’d heard, from my mother, that the bundles of joy had come along – eventually – one, two, three – and then had stopped coming, but three was enough to satisfy his mother. More than might have been expected.

I’d heard that news about him from Mother for years, the telling a reproach and a hope that telling it often enough might prompt me, eventually, to take his example. I hadn’t seen him in all those years, and now I hoped I never would, because the image I had of him, in those more perfect days, still showed perfect, for me, in memory. Perfect except for the end.

But best not to dwell on disappointments of the heart, of the past. Everyone has had them – everyone whose hearts were alive, at least – and no one ever died from them. And others seldom care to hear of the heartaches, or suffer the tears, of others. Even for those who shed them, the tears seem almost foolish, for sure futile, later on. I’d shed my share – for him and others – and I knew they’d stop, and they’d never change the outcome. So why shed them? A waste of time and energy. (Hardened hearts are easy to muster between times of loves and heartaches.)

To no one’s surprise, though still to our dismay, this year as every year, the Houston summer started early, and ran long and hot and humid. Those who could, escaped. I went myself to Santa Fe for some weeks, where other Houstonians – Grace Spaulding John, Beulah Ayars, Billy Larkin – gave me a readymade circle of acquaintance, if not real friendship. I’d had a small fling with Billy as soon as I moved back from New York – nothing serious; both of us knew that from the beginning, though it had been nice, and I could have seen it going on until one or the other of us found the fling that would be serious.

But Billy had other ideas – other, and younger, ideas. And so we’d kissed a lackluster goodbye kiss one morning at my kitchen table, after coffee – and it had been the last kiss, whether of hello, of passion, or of goodbye, we’d kissed. C’est la vie, as I found myself saying more and more often as the years passed. But, even though we’d kissed our last goodbye, so we thought, it might be fun (in many ways) spending time with him again, in the high altitude of Santa Fe, where the thin air sometimes leads to light heads (sometimes even as light as the heels), and then … who knew what might happen?

It certainly would be fun spending time with Grace, who was a woman in charge, a woman who knew her mind, and made sure those around her bent to it. Husbands (and lovers?) included. She had married young and badly, and then older and well (to a descendant of Sam Houston the second time), and now reigned over one wing of the Houston art world. She did not let husband and children interfere with her art and her travel – and they only seemed to adore her the more for it. She went to Europe, to New York (where she studied at Laurelton Hall, the Tiffany estate – hence the lush richness of her paintings), and to Mexico. There she made regular visits (again, in search of lush richness) and even proposed a book describing her travels and illustrated with her “quaint” but delightful linocuts and sketches. “Formidable” was a term that could be used to describe several of the women of Houston art, and certainly Grace earned that honorific as completely as any.

Part 9: Santa Fe Summer

A summer in the cool high desert, of cool tall drinks drunk in honeysuckle scented, hollyhock encircled gardens, of evening mesquite fires crackling in kiva fireplaces, within thick adobe walls, need fear no competition for our affections from the heavy, humid Houston heat, for those who could afford the journey and the stay. (And, of course, with Billy there I might be looking at more warmth than even the crackling logs could promise. Hope springs eternal.)

But such daydreams can survive only when there’s no reality intruding to burst them. And that proved not to be the fate of my Santa Fe daydreams that summer. Billy made clear early on that he would be otherwise occupied. Grace was somewhat irritable at the tepid reception of her most recent exhibition – some of her Mexico paintings, which should have been in vogue, but had to hang against powerful works by the actual Mexican artists – a stop in Houston of a national tour changing minds and eyes when it came to what art could be. Pretty no longer seemed enough, and pretty seemed the lifeblood of Grace’s art. Beulah, a grandmother who had come to art late, after she’d finished her duty as daughter, wife, mother, was her usual steady self. But she could not keep the crew rowing the same direction by herself.

After a few rocky days, I too sought to be occupied otherwise, and found such occupation sometimes on late-night strolls in the Plaza – or (I’m embarrassed to say) in the shadows of old adobe churches a time or two, with those who knew the churches, and their hidden nooks and crannies, well. Holy orders do not preclude all interaction with the world, it would appear.

We had pooled our funds to rent the Gerald Cassidy house out Canyon Road, a long, but pleasant walk from the Plaza, a walk offering many interesting possibilities most evenings. Cassidy had died in 1934, leaving the house available to be rented. It was more than ample for the four of us, though one must be discrete even when sharing large houses with knowing friends. And so I never took new friends there, making the long dark stretches of Canyon Road all the more appealing.

One evening, after a small dinner party at Witter Byner’s house – the one he shared for decades with his lover, Richard Hunt – the notorious (though mostly ironically so) Spud Johnson filling the fourth place at the table – I decided, instead of going directly back to Canyon Road, to take a paseo through the Plaza. I needed to walk off a bit of Byner’s delicious dinner (Richard’s, I think, more accurately), and let the more than drinkable wine breathe the night air. And at that hour one might even make new friends; some men become so friendly at that hour, after glasses of drinkable wine. I felt in a particularly friendly mood myself.

And so I walked down to the Plaza, and around it and across it for a time that I trusted was not too long, but long enough for my potential friendliness to be apparent to any who might be feeling friendly too.

After a while of walking, I noticed a man sitting on a bench, watching me as I strolled. About my age, or perhaps a few years older – but not disqualifyingly so. Strong features; greying blond hair. Starched shirt opened a button or two; chinos crisply creased. Our eyes met, and then, after a long moment, glanced elsewhere, as eyes do at such times and places. But then they met again, and again, until neither of us had any doubt that we were both feeling friendly that night, in want of new friends – one anyway, even though it might be a brief friendship only. Time would tell about that. But at such times, for such men, brief friendship may be friendship enough.

And so I smiled a discrete smile and he discretely smiled back. I nodded toward the empty other end of the bench on which he sat, and he nodded to agree that it was empty – but needn’t be. I sat, and we exchanged observations about the splendid, cool evening. Almost before we knew what was happening, we were becoming the best of friends – at least for the evening – against a wall in a dim deserted side street, steps from the Palace of the Governors. Such things can happen on cool summer nights in the high desert, and elsewhere, if you let them.

This turned out not to be a friendship for that evening only. He told me his name – Russell D., and I remembered it. From New Orleans as much as any place, but recently returned from China and Japan, where he’d written oriental observations for American newspapers. An artist himself, it piqued his interest hearing that my summer housemate was one of the leading artists of Houston. Houston, he said, might be a town he’d want to try out – from all he'd heard since his return from the Far East. Could it use another artist, did I think? Yes, indeed, I thought so. And I knew all the contacts he’d need to find his footing there. I could even facilitate his first contacts by introducing him to Grace before any of us left Santa Fe.

I should have known by then to be wary of such a rush of enthusiasm for a new “friend.” Years of living and scores of such friends should have taught me. But life doesn’t work that way. Which is all I really know for all my experience. And so I invited him to come for drinks some afternoon soon – which he did the very next afternoon – and I introduced him to Grace and Beulah, with whom he made an instant hit, and Billy, who held out a little longer – observing, appraising, sizing-up – before he too approved.

Thus Russell became a regular visitor to our Canyon Road casa, for afternoon drinks, chez nous suppers, and, when the drinks had flowed down the throats too freely to make possible the long walk back to his rented room near the Plaza, for overnight stays, sharing my bed, which all tacitly agreed to understand as entirely chaste. Even Billy pretended to understand it so, though once or twice, after evenings of especially plentiful drinks, his barely veiled flamboyance suggested that he’d be willing, if invited, to join us in making it less so. But that might be a step too far even with housemates as sophisticated as Grace and Beulah. I made as clear as I could that it would certainly be a step too far for me, and Billy acquiesced, at least as far as what might happen within the confines of our compound. What happened elsewhere, of course, could be no one else’s business, aside from those directly involved in the happening.

By the time we packed our bags and began the long drive back to Houston, all understood that we’d be welcoming Russell as a new Houstonian, as soon as he could complete remaining business in New Mexico – a mural he’d agreed to do for Mabel Dodge Luhan’s Taos house – of an arroyo gushing with water after a flooding rain – a sight he’d never seen, but thought an intriguing paradox for a near-desert setting. Mabel, a distant cousin of mine, through New England ancestors, many generations back, found Russell, and his Far East stories, so intriguing that she agreed to his unlikely mural suggestion.

One evening – it would be our last together for a while, and my last in New Mexico that summer – we, Russell and I, made our polite excuses and prepared to leave Mabel’s dinner party early: we had such a long drive back to Santa Fe from Taos, and I’d be starting that long drive back to Houston in the morning. Ever the vivacious, cordial host, Mabel said she understood, and walked with us to the door.

“We must do it again next summer. Won’t that be fun to look forward to?”

During the evening, after drinks and wine aplenty, she had made her play for Russell – and not succeeded. But ever the philosopher, whose philosophy seemed to be “Nothing ventured, nothing gained,” she did not hold grudges – not about such things as that. As we walked to the door, she bid us an exuberant farewell, and hinted to me, with a look, that she knew the situation – and thought it splendid that at least one of us would be keeping such an “intriguing” new find as Russell “in the family.”

Part 10: New Year's Eve!

Sometimes the future looks to be clear and happy sailing in smooth sunny seas all the way to the horizon, as though all the disparate, even dissonant, elements have come together in a harmony that will go on for ever. And then, in an instant, not.

I returned from Santa Fe in the fall of 1937 full of plans; returned after a delightful summer of hot dry days and cool dry evenings, and, thanks in no small part to Russell, hot delightful nights; returned to an empty house which, in my plan, would soon no longer be so empty. It had not yet been fully resolved that he would take up residence with me in my family house in Quality Hill. Not resolved between the two of us, that is, though in my mind there remained nothing needing resolving. Though it might still be months before he finished in Santa Fe and came to join me in filling what I now saw as “our” house, the plans were made – in my mind, at least.

When I thought of Russell I felt giddy and foolish – like a schoolboy in the scarlet heat of first love. Except that I was not a schoolboy and this was not first love – or fifth or fiftieth – so foolish indeed to give myself to it so fully as I did, or let myself be captured by it. By now I knew the chances were that heartache lay ahead. I knew that I’d be wiser to escape this captivity of love early, as I had not escaped others and lived to cry for it.

To cry for it, but not to regret it, which made the crying, and fond remembering, worth the pain. Might this be the love that would not dissolve in tears? Even if the chance were slim, any chance at all seemed worth the risk. Unlike the schoolboy, by now I knew I wouldn't die from love lost - and so I'd be foolish (indeed) to turn away from the possibility of love gained.

That, though, was for the future. For now, what I needed was that ship that would take me to the clear horizon. How would I be able to get through the months to the joy I anticipated – or at least hoped for?

At such euphoric stages, one sometimes feels the urge to devote one’s self to higher things – and almost as often fails in doing so. I made a pledge to find some higher thing to further, something that would both hold my interest and edify my soul as I sacrificed for a greater good – and awaited Russell. Finding such a combination, of the interesting and the edifying, did not prove easy. By nature I found maintaining interest in anything for long (and perhaps also anyone, I sometimes feared) a challenge. I might be, I sometimes feared, a dilettante of both action and affection.

Working for the betterment of the poor might seem the obvious choice of a “good work.” Not that I was rich myself, but, being far from poor, surely I could do something. Or mentoring the young. Didn’t I have valuable things to teach? Or visiting the old and sick, at least. And yet I knew that I would do none of those things – knew, because I knew myself so well after so many resolutions made and broken, so many instances of “walking by on the other side.” Not from heartlessness or indifference; I felt the pain of others, empathized, at least, felt the urge to help. But from fear – fear of ties and specters and expectations. Fears that made no rational sense – but then fears don’t have to.

If it would not be “good works,” then there was my writing, of course. Now that I had agreed to write a play for Margo and her Community Players, I had that promise and that goal to keep me centered there. And there were the theater, dance, music programs of a new fall season. Ted Shawn and his men would even be returning in December. And, while the weather held (which, thank goodness, in Houston it did till far into the winter months) there was the lure of strolls on Main Street and through Sam Houston Park to help fill the solitary evenings. These I would need until Russell came. (Though any new friends I might make there would only be in passing, with him in the center of my plan.)

But how seldom life acquiesces to our plans. The wonder is that we keep making them, especially the more mature among us, even in the face of experience and evidence.

Perhaps it was because my heart longed so for Russell, and that the longing would be going on for months unfulfilled, that another found a way into my affection, even as stars for the other sparkled so bright, that I didn’t notice his entry until it was too late to fight against it.

On New Year’s Eve, Wilma called to invite me to one of her spontaneous parties.

“We’ve got a quart of likker – lousy bourbon whiskey, but who’s complaining? The play’s closed and it’s New Years Eve, so some of the boys and I are bidding both the play and the year goodbye around my radio for the countdown – and drinking lots of toasts to the new year and to new plays. Come over and join us. It will be fun. Even old guys like you need to drink toasts on New Year’s Eve. I’ve got mistletoe left from Christmas, and that dream walking, Carden Bailey, will be here. Fair game for kissing, I’d say. At least I’m hoping to kiss him – and maybe you can too.”

Though I protested at her use of the description “old,” I thanked her for the invitation, and said I’d get to her place as soon as I could – not to drink all the likker or do all the kissing before I arrived.

Wilma lived just far enough away, and it was already late enough that I’d need to take a taxi, and who knew how long it would take to find one on New Year’s Eve. If I even could. The thought of the journey, even short as it was, and the drinking and the late night made me a little wary, but I knew that it would be lively at Wilma’s and I didn’t want to sit alone on this particular night – and then too there was the temptation of those “dreams walking” – plural because I had an idea of one or two more likely to be there, in addition to Cardy.

But that night all my plans went topsy-turvy. It was that night, at that party, that I met Lorin – for me not just a dream walking – but a dream walking in paradise – for a while, anyway.

Part 11: Lorin

“Come in, My Dear! And join the revelry!!”

Wilma handed me a glass of cheap “likker” as I came through the door of her apartment. I took it from her, smiled and took a sip, and then we kissed, cheek-to-cheek in the French style, but accompanied by the loud “muah” of American camp mockery of such fey Frenchified frippery.

“You already know many of the boys,” she said, as she gestured with a sweep of her hand toward the roomful of handsome young men, like a self-satisfied madam: Cardy Bailey, Bill Hart, Albert Horrocks, Drew Robert-Shaw – and one I didn’t recognize.

“Do you know Lorin?” she asked, presenting him like a bud among the blossoms in full flower.

Lorin!

His green eyes captivated me, and a tsunami of red curls crashing over his forehead swept me away.

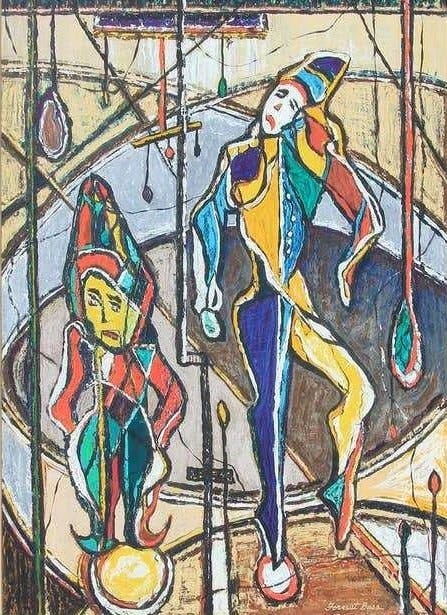

Lorin! Such a “sweet” boy, as they sometimes said, when it would really be “pansy” or “fairy” if just among themselves. Sometime in the fall he’d joined Margo’s theatre company; he designed sets for her productions, play after play, always creating exactly the right tone within which the actors could be alive, if not real, as they'd have to be to live in the real world the other side of the theatre doors. He also carved masks in wood - quite nice ones - taking Balinese originals as his models, but then making the style his own. It wasn't hard to see that he was creating worlds and wearing masks he needed to exist so he could live in them himself, never mind that world beyond the theatre doors.

I think it must have been that I saw in him elements of myself at his age (almost 20 years younger!) that first drew me to him, the struggles he seemed to be grappling with – bravely or desperately, or maybe both at once. Hard to know, or feel confident in, what he might have seen in me, a man so much older, that drew him to me – harder still to believe it might be genuine feeling and not simply grasping for a hold, any hold, as the treacherous ground crumbled away beneath him.

I don’t remember if he reached out a hand first, or if I did. I suppose I should take responsibility, as the mature one – the one old and experienced enough to know about such things – to know better.

Whichever reached out first, the proffered hand found a welcoming other.

As we worked together evenings and weekends at the Community Players theatre, in a repurposed city-owned building on the banks of Buffalo Bayou, he hung on my stories of the bohemian life in Paris and New York. Young as he was, he had traveled nowhere, though his dreams had already taken him around the world. The glaze of fascination came into his eyes as I told tales (tame ones, but fascinating none the less) of Paris: of Tchelitchew and Cocteau, names he did not know already; of Josephine Baker and Gertrude Stein, names he did know, from the magazines and the news. Stein had even made a stop in Houston during her American tour of 1934/35.

When I mentioned knowing both Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler in New York, his eyes widened. Their names he certainly did know. Wilma had taken him on as one of her Houston protégés (and projects), and had told him many stories about them – particularly her darling Parker. Which made my added stories, from a somewhat different angle, the more thrilling to him in his budding curiosity, even though I only hinted at some aspects in that early stage of our acquaintance, out of deference and caution with one so young.

I knew some of the questions he yearned to ask, though as yet he had neither the words nor the courage to ask them. I vowed that in my role as mentor to him, I would answer the questions truthfully and fully when he did ask them. I knew sometime he would. I knew it from remembering myself as a young man like him. How like a father with a son – and how unlike that relationship either of us had known with our own fathers. I had not yet begun to think I might also fill other roles in scenes we both might soon imagine. In a phrase that seemed to be becoming a favorite for me, those scenes were for now still “for the future.”

And then one crisp January evening, not long after our New Year’s Eve meeting, as we finished our work for Margo’s latest production-in-process, the future, as it linked the two of us, arrived.

He’d been telling me, with abundant youthful excitement in his voice, about his new job as apprentice window dresser at one of the city’s lesser department stores. I’d been regaling him (or was it attempting to impress him) with recollections of the splendid windows I’d seen all those years ago at Samaritaine and Le Bon Marché in Paris. As usual, he seemed captivated by my stories, looking at me with sweet puppy eyes, as he let my words transport him to places he ached to go.

How could even my worldly wisdom resist those eyes. It was as though I’d been looking into them my whole life and seeing the connection I’d always longed for. Never mind that he might be young enough to be my son. He was not my son, and he was old enough, so all the legal measures said, to know his own mind and make his own decisions. Except, of course, that neither of us had the legal right – some might also have said, the moral right, though I’d learned through painful decades to dismiss them as wrong – to make the decision (not a decision of the mind so much as one of the body) we were both in process of making then.

But why be coy? No one will ever read this – certainly none of the moral wrongers. It became clear that this was to be the night we would spend together, not as father-figure and substitute son, but as man and man, no matter the differences in our experiences, our backgrounds, our ages. The law of the land might label us outlaws – even segregate us as particularly evil in the prisons they might send us to if they found us out – but the law of nature, the nature we were as much part of as any others – gave us license to join with each other in the way we both wanted to join.

Since it had started to rain a bit, and since I had my car, and since he lived not far from my own house in Quality Hill – though in a neighborhood not quite so faux-grand, perhaps, a neighborhood where he lived with his mother and his many siblings, now that his father had started another family in Beaumont (started, actually, even before he acknowledged them and moved to join them) – I offered him a lift.

The rain made the offer and the acceptance easy. Not even the moral vigilantes could raise eyebrows – though in truth there were none of that ilk in Margo’s circle, so we had nothing to fear in that regard from our Community Players fellows. If anything, from them we might be in for a little gentle ribbing, all in good, encouraging fun, and a few slightly off-color innuendos (very slightly off-color – it was a mixed group, normal as well as queer, even for its thoroughly tolerant, if unspoken, views of such things).