Song of the Amorous Frogs (Complete)

A Story of Paris in the 1920s

I’d been working on my new story for days already, but even though I had what I thought a strong start, and a plot had begun to take shape as I wrote, a title eluded me. Then, as often happens, it came in a flash, when other concerns consumed me. But how striking, how right: “The Song of the Amorous Frogs.” Once heard, who would forget it, who would not take a second look?

It had come on a sun-pierced April day as I strode through the Jardin des Plantes. I was on my way to the Gare d’Austerlitz, where I would meet the train bringing Clem back from Toulouse. I had no time to spare. I’d lost myself completely in the critique of my cubist figures, given by my teacher, André Lhote, whose atelier I attended three mornings a week, and suddenly I was late.

Not even the fiercely modern Paris Metro could take me all the way from Montparnasse to Austerlitz. Someday maybe it would, but not yet. And horrendous traffic had stopped the autobus dead still, at Place Monge. It didn’t help that it was market day. Impatient, I decided to leave the bus and continue on foot. I so hated the thought of making Clem wait. And I hated even more the thought of not greeting him the moment he stepped off the train.

It had been so long since we’d said “Goodbye” at the same station when Clem left. As I had written then to my friend, Claudia, back in St. Louis: “Clem leaves today for Toulouse and it will be doleful here without him. No one fills his place.” Of course no one had, because no one ever could.

And so I was rushing through the garden, where the two of us often strolled at leisure on such days, flâneurs savoring the air scented by spring flowers and delighting in the puffs of pink petals fallen from the flowering trees and swirled into the air by gusts of wind. Spring was my favorite season in Paris – until summer, fall and winter became my favorites in their turn.

But that day, instead of the melodies of song birds, I heard only the crunch of gravel under my shoes as I hurried – a muted crunch, since in Paris even the gravel was refined. I hurried past the impeccably Parisian Hôtel de Magny; the Gloriette de Buffon, high up atop the maze hill; and the Ménagerie, where Rousseau had seen, and learned all he knew about, the tigers and zebras and imaginary jungles that fill his paintings. I gave none of them a second glance as I huffed and puffed like a train myself toward the station.

Then, suddenly, even the gravel crunch disappeared, supplanted by a booming screech, the like of which I’d never heard anywhere, and certainly not in Paris. It came from a trough of water plants some yards away, in the plotted garden across from the glass houses. Clem and I had walked past the trough many times, on our way to the tunnel entrance to the Alpine Garden, but never before had I heard such a racket. Time after time it pulsed through the spring air and pierced my ears.

At last I realized that the dreadful screech was the sound of frogs in the grip of whatever lust is called for frogs. Surely there had to be some beautiful phrase in French to elevate even the horrible noise I heard into the realm of gorgeousness, if only I knew it. But I didn’t. So I was left only with the din.

But it was Paris – the Paris I’d dreamed of through long (not quite, but almost, interminable) dreary years in St. Louis, before I finished my degree at Washington University, and made my escape abroad. It was Paris, Paris in the 1920s, Paris made not just for art and light and dining, but also, as they say, for love. And so, of course, the gorgeous phrase reached my ear almost as soon as I became aware that I needed it:

“C’est la saison de l’amour.”

Of course! “It’s the season of love.” I heard the words spoken by the chic Parisian grand-mère to the petite granddaughter who stood beside her, clutching two fingers of her right hand as they peered into the brackish water, for a glimpse of the creatures whose voices – fueled by love – outstripped their bodies by multiples of tens.

“L’amour?” the innocent one asked, looking up at her grandmother’s kind, knowing face.

“Oui, ma Cherie. Tu comprendras bientôt. You will understand soon.”

And with the phrase that transformed the awful sound into that beautiful thing, amour – a thing I understood myself, thanks to Paris and Clem – came the title of my story: “The Song of the Amorous Frogs.”

I worked out the phrase exactly as I rushed on. Gare d’Austerlitz was still fifteen minutes away, even if I hurried, almost at a run. And then the labyrinth of stairs and tunnels and platforms to negotiate. And if the train happened to be early …

I rushed on, thinking of Clem and of the amorous frogs and how now, with him back in my arms and my bed, the story would flow – like our love, now that we were to be together once again.

II

We met in Colorado Springs the first summer of the war, where I’d gone to visit my sister and her husband, who were there seeking a cure in the pure mountain air for his tuberculosis at one of the sanatoriums offering hope to the near hopeless. Clem was there from Chicago with his young wife, a patient too. Consumption, as so many still called it, had her in its grip. She would be consumed by it.

Clem stayed by her side through the days, weeks, months of her pitiful decline. My sister and brother-in-law (he would recover and they’d return to their life in Houston), befriended them and offered what encouragement they could, in the face of a reality that did not suggest recovery for Clem’s wife. By the time I visited, even Clem had come to know that his beloved would not recover – a truth she had accepted already.

Only a month separated me from Clem in age, but the unimaginable agony of a beloved’s certain death – unimaginable to me – marked a difference in our understandings of loss and pain that seemed almost unbridgeable. Though I had such little to offer of experience or wisdom, my company seemed to give him some comfort at the times he could not be by her side.

Sometimes, in the evening, after an anguished day, while the nurses prepared her for her fitful night, he and I would sit together in the deep white chairs on the wide porch – mostly sitting silent, watching the sun set over the mountains in the near distance. Unless he spoke, I tried to stay quiet out of fear that some unintended glibness might infuse anything I said – unintended, but perhaps ignorantly unavoidable, because I had not yet had to feel such excruciation as fate had thrust upon him, upon them. They were both so young to have to know such heartbreak.

I’d finished my first year of college, and with a patriotic fervor reserved for the young and unknowing, I’d enlisted in the Army the afternoon of the day I’d finished my last exam in the morning. I was just old enough that I could join without my parents’ consent, so I told them only after signing the forms. There’d been tears from my mother, of course, and a stern reprimand from my father. But after only a little while their mood shifted to resigned pride in their only son. Since I had a few days to pass before reporting, we all agreed that I should make the journey to Colorado. There was no knowing when – or if – I’d have the chance again.

On my last evening, after my few days there, sitting on the porch alone with Clem, I knew that I dreaded leaving more than I’d ever dreaded anything before – though I couldn’t say, even to myself, exactly why. We sat in our usual silence until long after the sun had sunk below the mountaintops. And then it was time for me to pack, and say my goodbyes to sister and brother, before an early morning departure.

I longed to reach out and touch Clem to let him know how completely I’d still be with him, even though I’d gone across the country, and perhaps across the ocean. But I had no knowledge of how to do such a presumptuous thing. He stood when I did, and after a moment, looking at me with tears in his eyes, he reached forward and put his arms around me and held me close.

“I’ll miss you,” he said. “I don’t know if I have the strength to see this through without you.”

I had no words. I held him close too, as a brother would. But no, not a brother. Something else; something that frightened me even though I couldn’t name it. We stood there in the dark for a long minute, our arms around each other, he weeping softly; I felt his tears on my cheek. When I pulled away and turned to go, tears had come into my eyes too.

III

The months passed. I finished my basic training, and, with a year of college already, went into officer school. Then the Spanish flu struck, spreading terror and death around the world. I fell sick with it, but after a perilous illness, recovered.

My sister, in Houston, did not recover. In her last letter, which I received shortly before the telegram telling me of her own death, she told me that Clem's wife had died some while before. She did not include his address so that I could send already long overdue condolences. And before I could even write a return, she’d died too.

When I read the sad news, even as I tried to share the pain I knew he felt, the thought came to me: "You could be as a wife to him, if that's what he desires." Though I hardly knew what it could mean. But I did know I should never say it to anyone - certainly not to him.

My orders assigned me to Europe, to France, though not to the trenches that filled even the bravest of us with trepidation as we heard their horrors described in stark, somber details. My duty would be in Paris, a minor member of the diplomatic efforts that would soon be undertaking major tasks as the likely outcome of the war became clearer.

Even though not an infantryman bound for battle, I shipped over on a transport with a thousand other soldiers. The frisson of anxious anticipation for what lay ahead seemed to keep the ship afloat as much as the ocean waters it traversed. By the time our ship docked at Saint-Nazaire, word had come that the armistice would be signed within days. I arrived in Paris in time to be told that I’d be going home almost immediately – that the war was over and my part in it, only preparation that saw no action, was over too.

I had only days for a first glimpse of Paris – the Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe, Sacré-Coeur, and the day and night celebrations in all the streets that made such a misnomer of the term, “The Peace.” Paris had meant nothing to me growing up in Texas, and even as I heard something of it, and the wonders it offered, during that first college year, I hardly thought of it except as a far away, foreign place. But seeing it, feeling it, even for just a few days, transformed it into a beacon for me, to which I knew I’d return soon, if I could.

IV

But “soon” stretched into years. With the war over, and the world turning to the new normal in which everything seemed different, and the future unknown, exciting, unnerving, I returned to St. Louis and Washington U. to finish my degree. That done, and with an invested legacy from my sister, I made plans to return to Paris – which, after that brief glimpse, and with a blossoming romantic spirit, had transformed, for me, from nothing to very much indeed. I began to know that the future I hoped for – a future just coming into focus – a future so different from that my Houston and St. Louis world said was inevitable – and right – could only happen in Paris. And, though I didn’t yet have the words, or courage, to say what I thought, hoped, knew that future had to be if I was to be my true self, and happy in it, I had begun to know in my soul that it was a reality so different than all that everyone expected from me, that I had to leave – to go to Paris – to achieve it.

In December of 1921, I sailed from New York on the steamship Leopoldina, bound for Le Havre. As it happened, my fellow passengers included a young couple named Hemingway – he from Chicago, she from St. Louis, though I had never met her during my years there. Taking a chance, I asked Ernest – that was his name – if he knew Clem. He didn’t, of course. But an obliging fellow, he offered to ask a Chicago friend, already in Paris, in case he might know him.

And to my surprise, the friend did know Clem. And – miracle! – the friend said that Clem was in Paris, had been for some time, and he had his address, at least the address of the rented room Clem occupied when he’d seen him last at the end of summer: a number on rue Cardinal Lemoine, just off Place de la Contrascarpe, in the 5th arrondissement, in the left bank Latin Quarter, far away from the fashionable Paris of the Champs-Élysées and Opéra Garnier.

As soon as I’d settled into my cheap hotel on the Quai Voltaire – the same hotel that the notorious Oscar Wilde had once stayed in, after his disgrace and imprisonment – I made my way to Montagne Sainte-Geneviève in search of the address I’d been given. I took the autobus along the Seine to Boulevard Saint-Michel, and transferred to another route, going up across Boulevard Saint-Germain, past the Cluny and the Sorbonne, to Rue Soufflot – with the magnificent Luxembourg, which Clem and I would come to love so dearly, to the right.

There I got off and walked up toward the Panthéon, final resting place of French heros. A brisk December wind blew toward me as I walked up the hill, but, under the clear blue winter sky, it invigorated rather than chilled. Even at mid-morning, the cafés along the avenue bustled with Parisians lingering over café and croissant, or, for some, already, Pernod. I passed Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, with its majestic, and rare, stone rood screen – the church Clem and I would come to think our favorite in all of Paris.

I walked up rue Clovis, past the fragment of the old Medieval city wall of Philip II Augustus, jutting into the sidewalk. The scent of innumerable dogs, laying claim to the now decrepit fortification, nipped my nose. Even in Paris – but in Paris it almost seemed exotic perfume. At rue Cardinal Lemoine I turned right and continued up the hill to number 75. The massive wooden gate fronting the street was closed, but I tried the door cut into it – which was unlocked. I went in.

Before me, a paved carriageway went up between two buildings toward what looked to be a well tended – though, in December, leafless – garden. No concierge came out to warn me off with a gruff “greeting” – perhaps in this quarter, not often frequented by foreigners, interlopers generally were not bold enough to come in uninvited. I walked boldly on, and, in a few steps, came into what, in spring, summer and fall must have been a lush country garden in the heart of the city.

Up three marble steps rose the epitome of an elegant French bourgeois residence – Second Empire, or maybe even Louis-Philippe – painted a pale pink, and with white shutters bracketing the windows, a white bench at a stone table to one side of the steps, and to the other, a grouping of now empty chipped, yellow Provençal pots. Even though so close to the busy street and Place, the atmosphere spoke only of quiet calm.

As I looked around the garden at the stark winter beauty, and imagined what a rich beauty it must burst into with the coming of spring, a maid – at least I took her for a maid; she did not have the bearing I supposed the Madame of such a Parisian house must certainly have – opened one half of the double inner door, and said, in a clipped, officious voice,

“Oui, monsieur?”

“I’m sorry. I don’t speak French. Je ne parle pas français.”

“Madame Le Floch n’est pas ici. Madame is not here.”

I tried to make her understand that I was not looking for her Madame – of whom, of course, I knew nothing – but rather that I was hoping to hear that Clem still lived somewhere here.

At the mention of his name, she brightened like a happy child.

“Ah, oui, Monsieur Clem. Il est là-bas. Au deuxième étage ,” and she pointed to a window at the top of the building across the garden, a garret window, of course, since it was Paris.

“L'escalier est là-bas,” and she pointed again, now to a closed door I’d passed as I walked up from the avenue.

“Thank you. Merci,” I said, nodding my head slightly.

She went back into the warm house and closed the door, but I sensed that she watched from the front window as I walked back to the door she’d pointed me to. I opened it and found a narrow stone stairway with a wooden banister, winding up in an elegant oval. I took the steps two at a time in my eagerness, and turned into the hallway at what I’d have called the third floor at home – but it was Paris, it was the “deuxième étage.”

I knocked on the door at the end, the one I supposed opened into the room of the window the maid had pointed out. I heard movement inside. After a moment, the door opened, and there he was. Clem! Not quite as I remembered him – a few years older, of course; perhaps matured and worn by the ordeal of his wife’s decline and death, but still the handsome man I’d come to feel so close to during the few short hours of the few short days we were together in Colorado Springs, those years ago.

I saw surprise on his face, almost shock, as he realized I stood there before him, with no hint ahead to help prepare him for the moment. Then, quickly, his face beamed, his eyes sparkled, his lips opened in a smile that filled me with the greatest satisfaction I’d ever felt. And he threw his arms around me and drew me to him, into the most genuine embrace I’d known till then.

“It’s you,” he said holding me close.

“It’s me,” I said. And then, as we held each other close, I said, “It’s us.”

V

And it WAS us, in ways that I, certainly, but I think also neither of us, could have imagined before. I didn’t spend even a single night in my Quai Voltaire hotel. We went there together the next day to collect my suitcase, after a night of not much sleep, together in Clem’s room, in the single bed, with much catching up and much holding close, but nothing else, that night. At the Quai Voltaire we took a moment to look out the window I hadn’t used, at the bustling Seine, crowded with boats – some for pleasure, but many more for the business of bringing and taking the goods and materials of a vast city and a rich, fertile region. We looked across the river at the Louvre and the Jardin des Tuileries, which we would explore together in the months to come.

And once on the street again, we took turns carrying my suitcase – which wasn’t heavy – as we walked through the Left Bank streets, past Église Saint-Germain-des-Prés – we couldn’t resist the temptation to stop in, the stained glass window transforming the floor into a glittering oriental carpet just as we entered the hushed, dark sanctuary – and along the Boulevard Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and then up Rue Saint-Jacques, through ancient streets, past bookstores and buzzing bistros in the busy student quarter, back to the room overlooking the garden, which was now “ours.”

It was with trepidation that we walked across the garden that first evening, and into the main house to tell, with whatever persuasive charm we could summon, Madame Le Floch the news that we would now be two in the room.

“Dan le seul lit? In the one bed?”

“Yes, only the one.”

And after looking at us for a long moment with slightly reproving (but not condemning) pursed lips, and since there would be no need for furniture moving, and no added expense for her from additional linens, she said only, “Certainement.” Which seemed to dismiss the subject from all future need for discussion.

Over the next months we had the joy of seeing, through our garret window, the bark on the Plane Tree limbs take on the luminous hue of spring revival, put out their new pale buds, which soon turned to deep green leaves, which rustled in the spring breezes, making music for us to listen to as we lay together in the bed on crisp March mornings, wishing for coffee, but not yet quite ready to take our arms from around each other, and go out to the cafés for it, and for buttery croissants crisper than the crisp air, or toothsome tartines slathered with apricot jam.

Clem had come to Paris running away from memories at home. He’d stayed mostly to himself, so, aside from the Chicago friend who’d given the information of his address, and one or two others he saw once in a while – not often – his circle of human contact seemed almost entirely confined to the other inhabitants of the buildings around Madame Le Floch’s wintery garden. I knew no one. So we had few distractions as we warmed the chilly days with deepening closeness.

As it happened, the Hemingways took a small apartment just across Cardinal Lemoine, also a garret, like ours, but even less tainted with luxury – hardly even whispers of heat or running water. We saw them sometimes, at least to greet, along the street or sitting in cafes around the Place de la Contrascarpe – more often Hadley than Ernest, whose journalism, and – more important – short story and novel writing took him out around the city long hours most days. He quickly became a full member of the expat American writing community – the community which coalesced around the pretense of writing, anyway – though Ernest and some of the others really wrote; Hadley often seemed lonely and sad. When we happened to see her, we did what we could to cheer her, but what we could do wasn’t much.

We had no need of cheering. Nor of a circle wider than our world of two. Clem had been in the city long enough already to know some of it’s delights, which he knew would delight me too. A favorite bistro, Lilane, just off Place Monge, where Madame’s greeting made us feel that it genuinely pleased her that we’d joined her for dinner, and where Monsieur, the chef, looked out from his tiny kitchen as we ate, to be sure we appreciated his cooking. The horse-chestnut trees in the Luxembourg, which Clem insisted I see when they bloomed – and which I mentioned to Ernest, who seemed to know nothing of them till then. Small things, like the magic music of school children singing in unison to start their day, at the school over the back garden wall; the water whooshing in the gutters in the mornings, diverted by street cleaners with their ancient brooms like hanks of stiff, wild hair; the half-closed eyes of waiters in long white aprons, bringing coffee to our tables in the heated sidewalk areas of Rue Soufflot cafes, once we had finally succumbed to the desire for coffee, after finishing the desires of bed.

We both had sensed those desires from the start, though neither of us had known what to make of them. That was not information fathers shared with sons when they had “the talk” then. Those discoveries we had to make ourselves.

We explored those backstreets and byways – so they were then – through the cold months of January and February, mapping the topography of unknown, unauthorized desires. We made whatever declarations needed to be made, with our bodies, rather than with words. The language of words has limits that bodies can transcend. But the declarations, without words, were as compelling as any spoken ones could be. By March, taking the journey together, we knew we’d reached what was, for us, our native land. And it was a land within the walls of Paris – metaphorical walls, unlike those crumbling Medieval fortifications of actual walls thrusting into the walkways of our neighborhood, but walls protecting us – protecting US – from the assaults that came with each letter from home, asking how we were, and who we were meeting, and where the meetings might lead.

VI

It didn’t often rain all day in Paris. Most days, if it rained at all, a shower passed over on it’s way south and east, and then the sun endeavored (not always successfully) to cut through the thin scrim of clouds lingering behind. But occasionally it did rain all day, starting before dawn and shifting back and forth from drizzle to downpour to drizzle far into a grey mid-day and afternoon.

On such days, what a joy it was lingering together in our room, the window onto the garden ajar – except on the cold, driving rain days – reading and sketching and talking, from time-to-time, about nothing in particular. Sometimes a low, rolling rumble of thunder would put us in mind of the more violent thunderstorms back home – a sort of violent nature not frequent in the nurturing Île-de-France.

We had a hotplate in our room, which Madame Le Floch pretended not to know, but Madame Le Floch knew everything that happened or existed on rue Cardinal Lemoine. So of course she did know, and for whatever reasons of her own, decided not to. On those wet, room-bound days we made our coffee and chocolate without going out, to drink along with the scraps and bits left from our purchases the day before, from the boulangerie on Monge, and the roving market on the Place. On such days we might stay in our BVDs until well past lunch. Just us guys, after all. Why not?

On one such morning in April, a sharp knock at the door disturbed our under garment-clad idyll, and the maid’s piercing voice said, “Câblogramme, pour Monsieur Clem.”

“Un moment, s'il vous plaît,” Clem said as he grabbed his trousers and pulled them on, and I moved far to the corner of the room, out of the line of sight of the door when opened.

“Pas de problème. Je vais le mettre sous la porte,” and the cable, in it’s envelope, slid under the door.

“Bon. Merci.” said Clem, his still unbuttoned trousers held up by his suspenders. He picked up the little paper missive and tore it open. His brow furrowed and his face darkened into a frown as he read it. I waited for him to speak, sensing that this was not a moment to press him.

He folded the paper and put it back into it’s envelope. After a suspenseful moment – longer than I could have imagined a moment to feel – he looked up.

“From my father. He’s asked me to go to Toulouse to meet him. He’s coming up from Spain for a few days on business, before he meets his ship home in Marseille.”

What a surprise. I had no idea that Clem’s father was in Europe. In fact, I had little idea of Clem’s father at all. Clem had hardly mentioned him, or anyone else in his family – nor me mine, though he’d known my sister and brother-in-law in Colorado, and she had, no doubt, told him all about “the folks back home.” That’s what most people do, with strangers, as they’re getting to know them enough to find other topics. But in Colorado, Clem had been so consumed by his wife’s sad decline, that nothing outside the moment seemed worth mentioning. And since I’d been in Paris, and even as he read the occasional letter from home, he hadn’t mentioned those in Chicago, beyond naming them, and I hadn’t asked. They seemed to have no part in the life we lived together, in our room, in Paris, so I hardly thought of them at all.

“Shall I go with you?” I asked. “I’ve never been south. I’ve heard that part of France is very different.”

“I’d better go alone. He says he’s got important family business to discuss. I don’t suppose it will be an amicable meeting – judging from the way he says it. I suspect he has some bone to pick with me. Whatever it is, I’d best go alone.”

“Of course. We can go together another time. Perhaps on our way somewhere in the summer. They say that everyone leaves Paris for the summer.”

“Yes, the summer.” And we said no more about it – until he mentioned that he’d be going the next day. Another surprise, that it was to be so soon.

That evening we went to Lilane, as we had so often, and enjoyed our dinner with the Madame, of langoustine raviolis and dorade grilled over rosemary branches – and Monsieur’s incomparable chocolate mousse. After dinner we walked back up the hill, through the wet streets, to Place de la Contrescarpe – lively as usual – and went into the café at the corner of rue Mouffetard, for a cognac to finish a perfect night – or to take it to its next stage.

This was the night we’d been building toward since that first day when I’d knocked at Clem’s door. Maybe even from those heart-rending nights on the porch of the sanatorium in Colorado. Maybe even, separately, each in our own time and in our own place, since long before we’d ever met and felt the something that neither of us understood. Now we understood, and saying the word love, which our bodies had spoken already, but not our tongues, became natural and easy. I fell asleep that night smelling the scent of his maleness, contented and centered as I had never been before.

VII

I saw Clem off at the Gare d’Austerlitz – watching the train puff and squeal leaving the station, until I could no longer see even a hint of it in the distance. And then I walked slowly, alone through the Jardin des Plantes, and back up the hill to our room, overlooking our garden, in our Paris – now all lonely places, since I was now alone in them.

But Clem would not be gone long. He said he’d be back as soon as he saw his father off – a week, perhaps. No matter what, he’d be coming back to Paris. And then we’d have the rest of our spring there, and our summer wherever we picked for les vacances, and then our fall, and after, in Paris. We’d start looking for an apartment as soon as he returned.

The next morning, as I lay alone in our bed, I heard the birds chirping, and fluttering through the leaves of the trees outside our window. The school children sang their morning songs. Madame Le Floch, standing on the marble porch across the garden, sang out the maid’s name in her high, harsh voice, “Françoise. Françoise, où-es?” I got out of bed and made our coffee – my coffee, one cup, not two – on our hot plate, and thought how long the day would be without Clem to share it.

But it was April in Paris, and Clem would be returning soon – as soon as he possibly could, and I didn’t begrudge his devotion to family – I felt the importance of family myself – but I also felt a chill, though the morning was warm, at my first day in Paris in weeks alone, without Clem.

When I finished my coffee, I took my sketch pad and walked down the hill, between Saint-Étienne-du-Mont and the Pantheon. The Eiffel Tower, thrusting elegantly into the soft spring sky, guided me as I walked down rue Soufflot – not stopping, this time, for coffee and croissant at our usual café, but nodding to our familiar waiter as I passed, who nodded back in his reserved, Parisian way. I crossed the busy Boul’Mich, bustling with morning traffic, and walked through the regal gate into the Jardin du Luxembourg.

I walked beneath the glorious chestnuts, bursting into bloom after a few days of warm sun, and passed the Medici Fountain off to my right. One night not long before, Clem and I had walked there together as the sun faded away. We saw a single pink rose floating in the water, like magic, since there was no rose bush from which it could have fallen. We’d been alone on the path, and to my surprise, and delight, Clem had taken my hand and twined his fingers with mine. I felt the flush of what must be love, of a sort, as I remembered it.

I spent the day alone, sketching in the garden. I sketched Bourgeois’s bronze L’Acteur Grec, with the dome of the Pantheon in the background. I sketched the basin with toy sailboats scudding over the rippling waters, as little boys with long guide-polls scurried after them around the stone basin rim. I sketched the Harde de cerfs by Leduc, the majestic beast with antlers flared out from his head like a spiky patinated halo.

I watched the men – the young and cocky along with the old and crafty – casting their pétanque orbs with deft twists of wrists at the courts on the west side of the garden, envying their comforting camaraderie. I thought perhaps I would take up pétanque, and join them one day. But not this day.

VIII

Though it seemed long indeed, finally the week passed, and I came back to our room after an early supper at Lilane – Madame and Chef both asked after Monsieur Clem, and sympathized that I must eat alone – to find a telegram slipped under the door: “Returning tomorrow. 2 PM train. Gare d’Austerlitz.”

That was all, but it was enough. That night, I hardly slept. But that night, excited anticipation disturbed my sleep, instead of the loneliness of the nights before. And in the morning I set out both our cups, in case he’d want a coffee when he returned that evening. I looked forward to brewing it for two again.

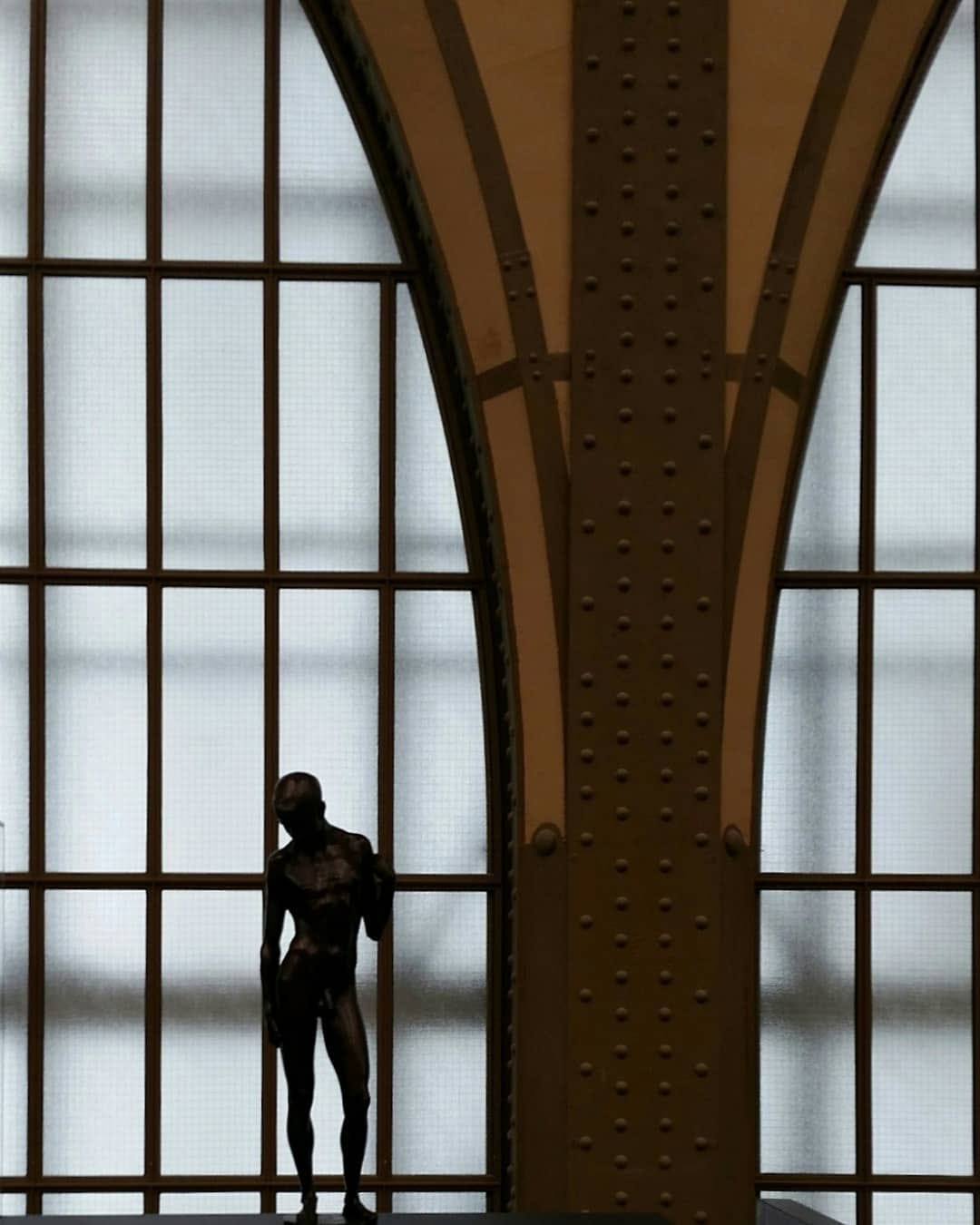

And so I was rushing through the Jardin des Plantes on the way to meet Clem’s train when I heard the amorous frogs and the title of my story came to me. Even rushed and excited as I was, I knew instantly that it was the perfect title. I smiled to myself with satisfaction at its rightness as I passed the Natural History Museum, where Clem and I had stood amazed one cold day as we took in the magnificent skeletons of the world’s great beasts arrayed through the vast gallery.

I crossed the chaotic boulevard and almost ran down the Quai d’Austerlitz, and up the steps and through the door, into the station. A glance at the board told me that Clem’s train had already arrived – early this time, when I would so much rather it had been at least as late as I was – and at a platform far at the other end of the station.

For whatever reasons, the great hall teemed that afternoon – perhaps it always did – and I dodged and weaved making my way to the platform listed on the board. By the time I reached it, the only arriving passengers remaining were a hunched old French woman, in a provincial brown coat and out-of-fashion hat, being lead by a spiffy boy of six or seven, perhaps her grandson, followed by a porter assisting with her three battered bags.

I looked in all directions for Clem, but he wasn’t there. In his eagerness at being back in Paris (and at soon to be seeing me, I hoped), he must have decided I’d missed his telegram, and wouldn’t be there to meet him. A bit disappointed, perhaps (?), but still eager, he must have struck out alone toward our safe retreat, on our idyllic garden, atop our impregnable hill, in our paradisical Paris. We may even have passed each other on different paths in the Jardin des Plants. Or he might have dashed into a taxi so that he could get there – get home – sooner. I considered a taxi myself, but decided that, with the crush of afternoon traffic, I’d make better time afoot.

My heart pounded, both from my almost sprint back from Austerlitz, and from anticipation, as I mounted the steps two at a time up to our floor. I had my key in my hand already as I reached our door, and had it in the lock fast as an arrow flying to a target.

“Clem!” I said as I turned the nob and opened our door.

But Clem was not there. Instead, I found another telegram, pushed under the door again, by Françoise, or perhaps Jérôme, the boy who helped with gardening or running errands or whatever else needed doing, and which a boy of 10 could be useful at. Once again, I tore it open.

“Not able to return as planned. More later.” That was all it said, but this time it seemed hardly enough. I wanted it to say so much more. There was so much more it could have said, though still it would probably not have been enough. I folded the paper and walked back down to the garden with it still in my hand. I sat in one of the garden chairs – like those the efficient women in the Luxembourg and the Tuileries rented for a few sous, rushing over as soon as you sat down, to be sure they got their due. There was no one to rush over in our garden. I sat alone there, until Françoise came down the marble steps carrying a bucket and mop, on her way to mop the black and white paving in our stair.

“Bonjour, Monsieur. Monsieur Clem n’est pas ici?”

No, Monsieur Clem n’est pas ici. I didn’t speak the words. That would have been too painful. And there was no need to say what was already so obvious, without words. There’d be time enough for saying things – and so many things to say – when he returned. Whenever that would be. For now, I sat silent in the garden, listening to the birds rustle in the leaves. Madame Le Floch leaned out a window above, and rasped out, “Françoise. Françoise, viens ici maintenant.”

And then looking down at me, she said, “Bonjour, Monsieur. Monsieur Clem n’est pas ici?”

“Non. N’est pas ici.” She was Madame, and Madame must be answered, no matter how painful, saying the words. “Peut-être la semaine prochaine.”

Maybe next week. Yes, next week for sure. And then Paris would be Paris again. Certainly it would.

The next day I went back to the Jardin des Plantes, not hurrying to the station as before, but to stroll alone, to pass the time until a solitary supper, a lonely night. I went by the basin where my title had come to me. But now, instead of the screech, I heard only quiet. The frogs seemed to have had their fill of love, for this year, at least. The grandmother and her granddaughter had gone. La saison de l’amour had passed. No doubt, there would be another season of love next year. And the year after. There always had been; there always would be. No doubt. And a year was not so long in the great scheme. A year made hardly a blip in the great scheme. And long before that, Clem would be back. Il le ferait certainement.

IX

But Clem did not return. After a while – weeks, not days – a letter arrived, postmarked Chicago. In it he explained that his father had convinced him it was imperative they return to Chicago together – that his family needed him, and that his family and his future must come first, before whatever it was keeping him in Paris. He did not put in words that thing – love – that Paris, and I, offered – and so the word had become unspoken once again – and even our bodies, no longer together, could not say it without words as they had done before. La saison de l’amour had passed indeed.

After a while, Madame Le Floch stopped asking about “Monsieur Clem?” She looked at me in her discerning French way, with a worldly wise look in her eye – softened by a touch of compassion for my manifest pain – and turned her comments to the fine weather, and the brevity of the white asparagus season. Françoise did not stop asking – about what I’d heard from Clem, what was keeping him away so long, when he would return, what a wonder it was that he had not returned already. But as time passed her questions moved from daily to weekly, and then shifted to a different tense: “Monsieur Clem had always liked the garden so much, hadn’t he?” A shift, and a tense, that seemed to put a period to my life with Clem as nothing else had.

As I began to accept that Clem would not return, my Paris life changed into a story without a plot. I drifted through the days, making my one cup of morning coffee on the clandestine hotplate in the room that had used to be “ours.” I still walked (how could such a solitary walk be called “strolling?”) beneath the chestnut trees in the Luxembourg, which had long-since shed their blossoms and now sported only dusty leaves, but now I passed the boat basin without a glance at the boats and the little boys chasing after them. I stood at the pétanque courts, but saw neither the crafty old players nor the cocky young ones, who still hurled their boules over the sand, and exulted at the soft click that knocked their rivals’ aside and left theirs paramount.

I still had my income from my sister’s legacy, and the post-war exchange rate still tilted massively in favor of my dollars, so I could stay in Paris, keep our (my) window on Madame’s garden, if I wished. And since I had no reason to wish otherwise, I stayed. Certainly nothing drew me back to America, to St. Louis or Houston – and since even Chicago, where part of me did long to be, could only be a torture – so close to Clem, but so cut off from him no matter how close, it would appear – nothing called me away from Paris.

But to be in a place, even Paris, without a purpose is painful, especially for the young. Youth is meant to be about the future, more even than the present – which may be sufficient for old men, clutching at it in the midst of a life now almost all past – but for those still young, is never enough – without love, which gives purpose to everything in youth. Since I no longer had love – gradually I came to accept it, to accept my powerlessness where love and Clem were coupled – what else did I have?

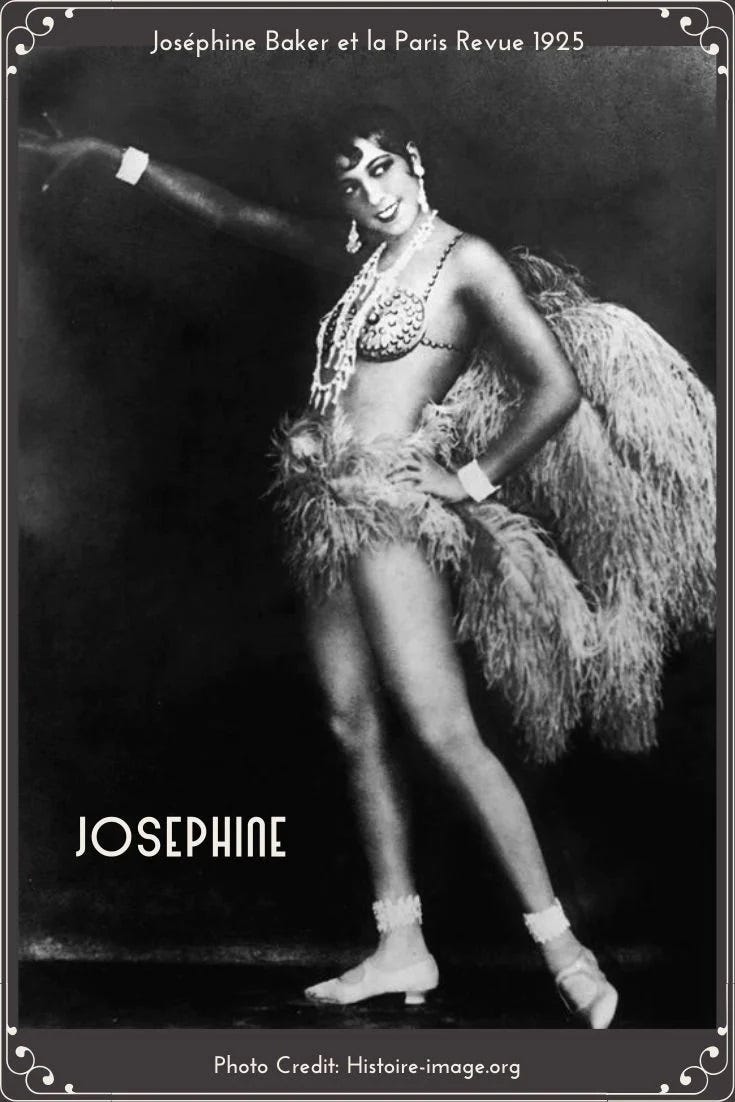

For other Americans, rushing across the ocean to liberating Paris, and libertine, at least by comparison to what they left back home, eager to flood the city with their dollars, a party had begun, which promised to go on, to grow only more captivating, compelling (and perhaps consuming) day by day, year by year, until blunted by some unforeseen, but perhaps inevitable, crash.

But crashes were for the future, and only the faint hearted allowed them to dampen the parties of the present. I began to think – to hope – that the parties might supply the plot that my life without Clem lacked. It would not be the life I’d planned, the one I’d dreamed of while he was with me, but it would be something with which to fill the void his leaving left.

I had never been much given to drink – it was a hazard that could destroy lives, I knew – some close to me. But it was not the Paris light and American dollars only that fueled the parties. And so, at times, even staid, abstemious Mid-westerners like me began to click the glass of that other fuel that flowed so freely in Paris, for the fleeing Americans especially, as it did not at home since prohibition had now become the law of the land in America – not just the law, but part of the Constitution. The French shook their heads at the insanity of America in this regard, as in so many others, even as they admired our machine modernness, and, secretly, our brashness, and longed to go there – to New York, at least.

Over the next months I began to explore a Paris – a world – a nether world, some might call it – I had no inkling of before, and one that Clem and I knew nothing of, even as we explored those secret by-ways we’d traversed together through the winter and spring. It was a world of inverts, of she-men, which at first I found shocking, and then repugnant – and then, gradually, intriguing. And then, at last, a world of respite from the loneliness of a life in the bleaker Paris I existed in without him.

This exploration began as I sat alone one evening in June, after a solitary dinner at a restaurant where no one knew me. I could no longer stand to go, alone, to Lilane, since both Madame and Chef could not help but ask about Clem whenever I dined there. Better to abandon them, though I regretted doing it, than to have reminders of Clem season each solitary dish.

That evening I had an unappetizing meal at a bistro that happened to be there, as I walked along Boulevard du Montparnasse, following a later than usual stay in Lhote’s atelier. Afterward, I went to Le Rotonde and sat on the sidewalk – and had coffee and liqueur. Even in the heart of always busy Montparnasse, there seemed to be a special crackle in the air that night.

As it happened, it was the evening of the annual Bal des Quat’z’Arts, the end-of-year bacchanal in which the art students of Paris vent their stress by shedding their inhibitions and their clothes. I had never seen anything like it.

I sat at my table a long time, putting off my return to my empty room overlooking Madame Le Floch’s garden. An early summer heat had arrived. I almost wished I’d ordered some drink with ice, instead of coffee. But habit, which did not require thought, dictated coffee.

As the hour (or two) passed, the tenor of the sidewalk traffic began to change. After a while, perhaps like a lobster in the water of a gradually heating pot, I snapped back to the present from whatever sad past of maudlin loneliness I’d receded into, and realized that young women with bare breasts and young men in loin cloths that barely covered even the essentials, had replaced the properly (and sometimes, chicly) dressed French men and women of less abandoned times.

I heard a reproving, or perhaps disbelieving, American accent from a table behind, as a woman loudly observed, “Can you believe this?! Jim and a cousin of Renee went to the ball last year – and Jim says never in all his life did he ever see such an orgy. He was ill for three days afterwards. Says it was the first and last time. Well, I had to come and see what he was going on about. My law! Now I see.” She almost succeeded in stifling a nervous titter.

I saw too. My eyes at last opened to the existence of a Paris in which things could happen that could not be written about in letters home. I decided that I might want to find out more about such things. But I was unsure how I could.

X

One morning, as I returned from one of my frequent, solitary walks in the Jardin, I saw Hadley coming out of her door, across rue Cardinal Lemoine – alone, as usual. I greeted her and walked across to exchange a few words. It had been some time since I’d seen them. Ernest, she said, had had to go away. Maybe to Spain, I thought, to research one of his bullfight pieces – or to the races somewhere, with who knew whom?

I invited her for a coffee on Place de la Contrescarpe. We, the left behind, could perhaps console each other with even our glum company for a little while. We talked a bit about St. Louis, and homesickness, about what we missed – summer evening drives in Forest Park, and the wild new music, jazz, being played aboard the “floating conservatories” that plied the Mississippi from their docks beneath the Eads Bridge. By now she had stopped asking about Clem, and I had stopped saying that I expected him to return to Paris, “any day.” By now, we silently agreed that he would not be returning.

Knowing loneliness as she did, and with compassion, she wondered if I might be able to find respite from my loneliness (even as she accepted that her own would not be mitigated) at a place Ernest had taken her once – just down the hill – the Bal Musette in rue de la Montagne de Sainte-Geneviève, number 46 – a festive spot filled with “flamboyant” people, mostly men. She had wondered, in fact, how he had come upon the place at all: Part of his getting to know “all of Paris,” he’d told her.

Clem and I had seen the place in our walks together, had seen some of the men (we supposed) who went through the door. But we had never gone in; we had not needed to. But now alone, I did go there that night. At the proper hour – late, but not too late; Paris was not a late-night city – at least my Paris wasn’t – I made my way down rue Descartes, behind Église Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, to the little place where it runs into the rue de la Montagne de Sainte-Geneviève. I stood there for a while, watching the taxis pull up to number 46, and the “flamboyant” men, of a sort, get out and disappear through the door – some with marcelled hair and what looked to be makeup to their eyes, lips and cheeks – sometimes even, it appeared, discretely holding hands. After a while of watching, and after many decisions to go back to “our” room, at last I pushed open the door and went in myself.

I went back other nights, not often, but often enough to discover that there were young men in Paris willing – indeed, eager – to do things I had not even imagined in my earlier days in St. Louis and Houston. And not always in expectation of Francs. Things I could not imagine in Paris either, until they taught them to me.

Over the next months, I discovered that there were other such places – some in Montparnesse, many far over on the other side of the Seine and up the hill in Montmartre. And that some of the Turkish baths were not just for bathing, and that the vespasienne dotting the city served functions (some would call them “unnatural” functions) in addition to relieving the calls of nature. The lessons I was learning were, I knew, some of those my father had warned against in an early letter, entreating me to be always vigilant against the “vices rampant in foreign cities – vices you should know nothing of.” The next months passed away as I came to know those vices.

XI

One warm spring evening, after I’d finished a late supper of the exotic, delicious borscht at Café Gaudeamus, and before going down the hill to the Bal Musette, I walked up toward the side steps of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont at the top of the street, my goal: to look at the Pantheon in the moonlight. High up, atop the dome, the massive cross seemed almost ghostly, washed in celestial light. I stood there for a moment, wondering at the beauty, and power, of a symbol in which I no longer had any faith.

Then I heard music drifting through the open doors of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont. It was beautiful music I’d never heard before. Modern, from the sound of it, though I was no student of music, certainly not of modern French music. But what I heard put me in mind of the haunting strains of Vinteuil’s Sonata described by Marcel Proust in his massive new novel, which I was then making my way through – the newly published translation by Scott Moncrieff, since my French fell far short of the challenge of the original. As in the novel, the music drew me in, first through the door of the church, where a printed program told me that the piece was a new piano trio by Fauré – and then, it drew me to a pew and to another world, of beauty and forgetting that I’d hardly known in the months since Clem had not returned.

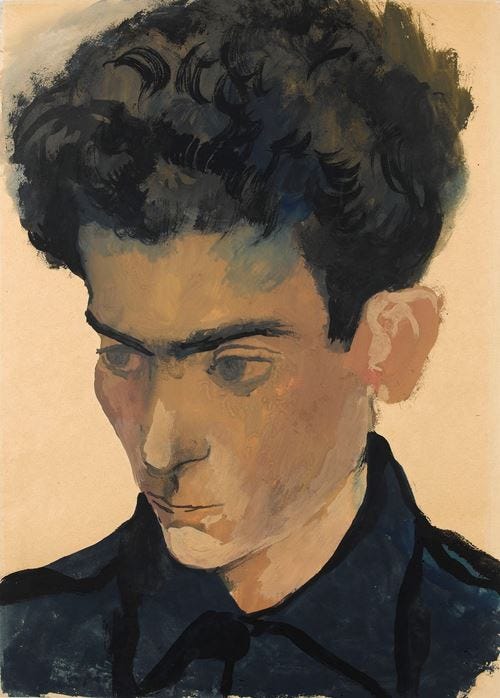

The music, flowing through the supernal space, beguiled me. From where I sat, I had a clear view of the cello. Whether it was the beautiful magic of his music, or the sheer beauty of the young cellist himself, I could not look away from him as he played. Black eyebrows struck accents to his pale, intense face, and a shock of black curls bobbed at his forehead as he dug into the notes. His long, tapered fingers flew over the strings, and the masterful back and forth strokes of his bow across his instrument commanded the music, and my gaze.

I sat mesmerized, watching him play and sway through the Andantino movement. Perhaps because my gaze compelled him, our eyes met, only for a moment, during the pause before the Allegro vivo. And then he began to play again.

The instant after the final powerful stroke, with the music still flooding through the sanctuary, as the applause – enthusiastic – began, and the three stood to take their bow, our eyes met again. This time, he made sure they did. And he did not let me look away, even as he smiled and bowed and nodded his head to the audience in appreciation – but most of all to me, so it seemed, in beckoning invitation.

As the applause subsided, and the audience began to move down the aisles and out the doors, and as the musicians put away their instruments, instead of going out, I walked forward, toward the rood screen and alter, toward the musicians, toward him – as I knew he knew I would. We smiled; we said, “Bon soir;” I told him, in my halting French, how his music moved me; he replied, in accented English, “Thank you very much.” All the while, our eyes spoke those things, clandestine things even in Paris, that eyes are best at speaking.

When he had said goodbye to his fellow musicians, and the church had almost emptied, except for us and the attendants, who were eager to close the doors and turn off the lights, we walked down the aisle together, he carrying his instrument, on his other shoulder, not between us, though it had been what first drew us together. But it’s task was done. We stopped for a time in the Place Sainte-Geneviève, where I’d first heard his music, flowing through the door – now quickly closed as soon as we’d gone through it. We stopped long enough to agree that we’d meet again the next night, at Gaudeamus, at 7 for un apéritif before he played again, and then a supper after. And then? Perhaps an evening.

Then he had to rush. He saw his autobus rounding the far corner of the Pantheon, and it would already be late when he reached home, he said. As he hurried up the street toward the stop in front of the École de Droit, he glanced back and smiled and said, “Tomorrow evening.”

I watched as he boarded the autobus, and I watched as it drove away. And then I turned to walk back to the room on Madame’s garden that was now mine alone. I would not go to the Bal Musette that night.

XII

When I unlocked my door, and opened it, I saw an envelope on the floor. I picked it up. As I looked at my name written on it, my heart pounded like a piston. I knew the hand instantly. It was Clem’s.

It was not a letter, with a postmark and a stamp. He’d written only my name across the envelope. And so it must have been delivered in person. He must have delivered it. He was in Paris!

The force of that realization flabbergasted me. I tore it open and took out the sheet and read the words that – HAD BEEN WRITTEN BY CLEM!

“I took the chance you were still here, and came to see you today. I am sorry you were not in. I am in Paris on business until Friday – at the Henri IV – across from Square Paul Langevin – where we used to walk sometimes. Do you remember?” Of course I remembered; I’d walked there, alone, many times since, remembering. “Busy all day tomorrow, but come to me at half-past five. I’ll tell them to expect you. You can go up to my room, if I’m late. We can catch up. It’s been so long.”

So long indeed. Too long, and yet even so, perhaps not long enough.

“PS: I am so sorry that Françoise is no longer with Madame. She was amusing, and sweet, even if a little thick.” Françoise had returned to her home village, somewhere in Normandy or Brittany, in the winter; her aging parents had called her home to look after them. I missed her too, even though she persisted, from time to time, to ask about Clem – and cluck at his absence – until her last days in Paris.

I almost flew down the stairs and across the garden to the house, to ask the new maid, Marie, about the one who had delivered the note.

“Un homme très gentil. Très beau,” adding the last to let me know that she knew more of my life than, perhaps, might be proper. Françoise would not have done that. But Marie smiled almost sweetly as she said it, making us confederates in a diverting secret.

But she had nothing more to offer in answer to my questions: when, name, bearing. I walked back across the quiet garden, my heart pounding less thunderously, and went back upstairs. But I sat in the window far into the night, looking out at the moonlit plane trees, which murmured softly when night breezes passed through their hand-large leaves – murmured, I sometimes thought, CLEM.

XIII

The next morning, after little sleep, I made my coffee as usual in my room, and washed myself, and went to my class with Lhote – as usual. But I could think of nothing but Clem, and how slowly the time passed. Le maître, disappointed perhaps that I had so imperfectly absorbed his teaching, made clear that my drawing that day did not please him. It did not please me either. But that day, drawing hardly seemed to matter. I put away my charcoals and drawing pad the instant I decently could – the instant Lhote had gone to his own studio, and left us to ourselves.

I made my way from the atelier to the Boulevard Montparnasse. The day was clear and warm, even for April in Paris. I walked and walked down the Boulevard, past Le Select, past La Rotonde, all the way to La Closerie des Lilas, not even glancing to see if there might be anyone I knew in any of them. Then I turned and walked into the long arm of the Luxembourg that reaches out toward the Observatory.

I passed Fontaine des Quatre-Parties-du-Monde without seeing it, and, when I had reached the Luxembourg proper, I walked beneath the pink-blooming chestnut trees and past the boat basin – where the little boys gamboled after their scudding boats as the whole world expected them to do on such days. I walked by without a notice.

I had no awareness of which streets they were that took me to Square Paul Langevin. My feet knew the way, thank goodness, since my mind stayed intently elsewhere. I arrived by 5, in more than good time for the appointment Clem had set. So instead of going into the hotel directly, where – who knew – I might sit alone for hours – I went into the Square, and sat on a bench from which I could see the door of the hotel. I sat there for a long while – I lost any sense of how long – watching and thinking and remembering.

Once again it was the season of pink petals, the season I loved, and the Square was full of the flowering trees that shed them. They covered the ground like pink spring snow. But since there was no breeze this day, they did not swirl up around me as they magically sometimes did. This day they lay on the gravel of the square, beautiful but still.

I remembered when Clem and I had walked among them, here and in other beautiful places around Paris, a year ago. I remembered how they overwhelmed my senses then. They still did, even though those senses had felt so much the pain of his absence since. Now it was a less abandoned joy they gave, but still a muted joy.

I looked up at the hotel and saw a window open on an upper floor. I could not see who opened it. Could it have been Clem? Perhaps. I had not seen him go through the door, but he could have finished his business sooner than he expected. He could be in his room now, laying out something with which he planned to welcome me, after his long absence. I wondered what he would say first when I knocked and he opened the door. Would his face have the same profoundly gratifying look of surprise and joy as that first night when I’d knocked on the door of his room – our room – my room above Madame Le Floch’s garden? How could I bear it if it did not? But even if it did, what difference, since he was leaving Paris tomorrow – so his note, slipped under my door, had said? One night; “catching up”; hearing, from his lips, what had happened, and, perhaps, why. What difference, when Saturday came, and he had gone again?

I had thought the tears had all been shed. Though I had not really thought so, perhaps, but only hoped. But they had not. My eyes wet with them, and my cheeks, I sat still on the bench, in sight of the door of the hotel, through which I did not see Clem go, for more minutes. So many, that 5:30 passed, and then 6. More than once I almost stood up to go across the Square, to the door, and in. But I did not. And I did not. And I did not. And at last – I had no idea how long it was – I knew that I would not. I knew that I could not.

I stood and walked through the gate into the rue des Écoles. I looked once again up at the windows of the Henri IV as I passed, wondering which window was Clem’s; wondering if he was looking out it, wondering if I would come; wondering if memories of him would make my coming certain. A lingering something made me sad thinking I might disappoint him.

It was spring again. La saison de l’amour had returned. Perhaps the amorous frogs might be screeching their love songs again in the Jardin des Plantes. I did not know. I had not been there in weeks, where he and I had walked so happily, in love, last year. But if they were – I supposed they were, since it was their season – it was a different year. It was different now.

I walked on up the rue and turned into Montagne Sainte-Geneviève – alone. I knew how to walk alone. Clem had taught me that.

As I walked, I knew that my age of innocence, with Clem, had ended – if there had really been an age of innocence since Adam’s fall. I sensed that a new age was beginning. I had no idea what to call it, what it would be. The age of possibility, perhaps? I passed the Bal Musette. Maybe I would be going back there later, who could know? But for now, if I hurried, I would be at Café Gaudeamus by 7.

XIV

As I approached Café Gaudeamus and looked through the window, before pushing through the door, I didn’t see my Cellist. The dreadful chill of disappointment sickened me. I reminded myself how I knew all along that he would not be there. Had I learned nothing of the ways of the world by now? I almost turned to walk back down the hill.

It was too early for the Bal Musette, but perhaps not so for a dinner of entrecôte, served in the subterranean depths of L’Ecurie on the corner of rue Laplace – accompanied by a mountain of frites and a heaped bowl of aioli, which migrated from table to table as the need arose - all served by the “hunchback of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont,” with his limp, and his Prince Valiant hair to his shoulders – so I thought of him this evening as I let the bitter disappointment fill me with spite. I thought, also, how foolish I’d been, not to have gone up to Clem, even if only for a night. One night would have been better than none, with only a likely tough steak for consolation after being stood up.

But then I saw him, sitting in a back corner of the café, his instrument in its case leaning against the wall. He looked around with a somber expression on his beautiful, pale face – perhaps expecting that he would be stood up too? Perhaps thinking how foolish he too was, not to be keeping an appointment set by some Clem of his own, instead of sitting alone in a café, waiting for a passing fancy whose time might already have passed. Perhaps grappling (both of us) to accept that there were many Clems in the world we were entering.

Or maybe he was thinking none of that – just half irritated that he’d made an effort, and got there early, only to be kept waiting by an unreliable American. But whatever he might (or might not) have been thinking, when I went through the door, and when he saw me, he smiled and nodded, and I smiled and nodded. And we entered this new realm of possibility, together.

“And so we have both kept our assignation,” he said, in his precise English-accented English, and with a light turn of his head and lifting of his black eyebrows. “This is a good sign for a long and happy life together,” and his faint smile on his pursed lips made clear that he spoke to be amusing, and amused. “Therefore, you may sit and join me.”

“How kind you are, to permit me,” I replied, as I sat in the chair he indicated.

“Yes, usually I am not so kind. Most cruel. I make an exception for you. I have a softness for young Americans of a certain beauty. Though not always a softness.”

I smiled at the suggestive possibilities of his banter, not sure if he knew how his phrase, in English, might be understood in the argot of some circles in England and America. Then the gleam in his eye, and the wry smile on his lips told me that he did know, and that he intended just such an understanding.

“Then you intend to make me your plaything?” I asked, joining him in a back and forth that had become familiar to me over the last months, but one that was not often so piquantly amusing with most, as I was finding it with him.

“As a cat does a mouse,” he retorted instantly. “And one of us, at least, will have great fun in the playing – until it is time for it to end, as such playings always must. And then, poor mouse.”

I could no longer maintain the mock-serious mask we’d tacitly agreed should accompany our gripping little comic opera. I smiled broadly at him, and said, “Yes, poor mouse,” and arched my own brow, and hoped my attempt at wit, to match his own, would not disappoint.

The cock of his head, and his appraising eye – and then a slight, tight smile on his enticing lips suggested success for my sortie – for this moment, at least – which was enough – for now.

“We will continue this after I play,” he said. “You will be there …” (it was not a question) “… and then after, we will have a supper, and then we will continue this. I am not expected a ma maison ce soir.”

And with that, there were no more questions to be asked and answered about what the evening (and the night) ahead would hold. And this new age of possibilities seemed to have launched, with vigor.

I did accompany him to hear him play as he had commanded, of course. The same trio of musicians, again in Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, but this night they played Debussy, a dissolving, lyrical magic carpet of music that transported me even more fully into the mesmerizing spell he cast over me with his artistry.

The next morning we stayed in my room overlooking Madame’s garden until well past 10. He had to hurry then, or be late to his class at the music conservatory where he studied (and also taught some of the younger musicians). For that, he would not be late. I watched from my window as he came out the door from the stair, into the garden, carrying his instrument in its case, against his shoulder. He passed Madame, as she came up the carriageway, carrying her marketing in net bags. She had been to Place Monge, and she had, without doubt, picked the best of each thing she chose.

“Bonjour, Madame,” he said, with a self-assurance that left no doubt as to the legitimacy in his being there, at that hour. “How is the white asparagus today?” he asked in his precise English. He spoke in English so that I could understand him, and know how confident and in control of all situations he was. “I must have some, if it is fine.”

“Indeed,” replied Madame, not revealing the least surprise at the presence of this stranger with a cello in her garden at such an hour – glancing, in fact, up at my window, as she said again, “Indeed.” And then, “It is fine. You must have some.”

I heard my cellist reply, “Then I shall!” as he hurried into the street.

Madame looked again toward my window. I nodded – and we both smiled.

XV

Thus began this new chapter in my Paris life, so unlike that I’d lived with Clem, that it was as though someone else had lived it, not me, and in some other universe. My Cellist, only a year or two younger then I, seemed so much younger in spirit. Either he had not yet been disappointed, or – more likely – he had a perhaps Gallic talent for leaving disappointments in the past.

And he was not content that we should be a universe of two. He knew everyone, it seemed, in the fevered world of Paris music and art, especially those of whatever nationality, who found in Paris a place where they could make their art without restraints, no matter how queer the art, or the world they constructed so that they’d have a fertile, and safe, milieu in which to make it – for most of them, so unlike what they had left behind, in native lands.

Like Pygmalion, he seemed to see the need to shape me for the higher life he intended we should live together for as long as our “playing” lasted. I felt no need to resist his shaping.

He began by taking me to an exhibition of new paintings by an artist I did not know, a woman “working in the modern mode … but in a way so different from those men, Picasso and the like.” A woman named Marie Laurencin, showing at Galerie Paul Rosenberg – paintings of a world of women, without men, almost unnerving in their frank femininity, sufficient in itself – just as ours was, in some respects, a world of men without women, a world of the frankly masculine that could embrace a feminine element in itself, which most men seemed afraid to grasp.

And then on to a hotel in the rue Jacob, temporary home and studio, to a Russian just arrived in Paris, Pavel Tchelitchew, fleeing the aftermath of revolution in his native Russia – as so many Russians in the city were – and fleeing, also, the constraints on men like him – and like my Cellist and me – which even the revolution had not loosened.

“He is doing my portrait,” my Cellist said, with pride, though with a tone that he intended should make the pride imperceptible. “Doing it very well, the likeness, and will show it at a gallery when he is done. I will be celebrated by all Paris, and not only for my music, as now.” He smiled, not modestly, but with the confidence that one day he would be celebrated by all Paris. “Inévitablement.”

Pavel – he insisted I call him that, even though his manner seemed very formal – very Russian, it could have been, and thus completely unfamiliar to me, since I had met no Russians before – that I knew of – Pavel showed us the portrait, finished to my eye, though perhaps not quite finished to his, since he had yet to sign, or title, it. But it was indeed a good likeness; it was my Cellist to the soul – literally to the soul in a way that few portraits – even none at all – I’d seen before, achieved. I had no doubt that it would someday make both artist and subject “celebrated by all Paris.”

He had only recently come to Paris from Berlin, with his close friend, a pianist, Allen Tanner, to see if a more permanent stay in the city, the center of the art world, might offer promise of a wider audience to laude what he knew to be his genius. Tanner, it turned out, had ties to Chicago, and so I asked if he knew Clem; and, it turned out, he did – though he said nothing more to indicate the nature of the “knowing,” and I asked no further questions.

Because of his Chicago connection, I mentioned my neighbors, Ernest and Hadley. Pavel said that they had met them “only the other evening,” on a visit to the salon of a monumental American woman, in the apartment she shared with another (not so monumental) American woman, in the rue de Fleurus – an apartment filled with art, including “the portrait of Gerturde, by Picasso himself.” And also chair cushions “stitched by Alice, to designs Picasso had done for them, specifically.” Picasso had not been at the salon that evening, but Gertrude had said – in her rather modern way – that she would introduce him “with gladness” the next time they both attended.

“This will be a great help,” Pavel said, confidently suggesting by his manner that the help would not flow in only one direction.

After a time of looking at – admiring, rather, is the more accurate term, and the one expected – Pavel’s paintings and drawings – some, of men entwined with each other, so shockingly explicit that I blushed seeing them, and my heart raced; these shown seldom, he said, and then only to “certain” men – we all went to a café in rue Jacob where we spent some considerable time drinking and talking, my Cellist and Tanner, about the advanced new music in the city, Pavel and I, about the art, which Pavel said needed “change and renewal. I will be one of those renewing it.”

Later, as my Cellist and I walked through the streets of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, on our way back to my room above Madame’s garden, on our way to another supper and evening together – he did not play this evening – I thought about how different it was, this Paris I’d been discovering with him, than the hermit-Paris I’d known with Clem, or even than the “debauched” one I’d known alone. And I thought about how much more exciting this Paris was than either of those I’d known before. And how I hoped it would be the one I’d be able to feast on far into the future. I thought this even as the demon of doubt whispered that only fools let such thoughts, and hopes, of “future” linger in their minds.

XVI

By the fall, my Cellist and I had become content with each other, and the tenor of the life we led together – when we were together, which was often, but not always, since we maintained our separate residences. He was well occupied with his music study and performance, and I, with art and writing. I even hoped to see my story, inspired by the amorous frogs, in print – if only I could ever end it. And so there were times when we did not see each other for a day or two together. We both seemed to feel such separations deeply – and we both seemed to want to make them as rare as necessary. When we stayed the night together, which we did more and more as the months passed, we stayed at my room, whether because he lived with family, with roommates, with a lover, I did not know. And I did not ask; I had learned enough by then to know that some things should not be asked – if the answer might not want to be heard.

Though he sometimes seemed strung as tightly as his instrument, I learned the signs saying he needed space and time to let the tension ease, and I took control of myself enough to give the space when he needed it, not purely from concern for him, but also to be sure I would not drive him off with expectations he was not able to fulfill, or not willing to. It had come to me some time before, and some time after Clem did not return, that perhaps part of a reason might have been a truth my love forced him to see, which he was not yet strong enough to bear.

As the leaves of Madame’s trees turned golden outside my window, and fell, we found the rhythm that made the music of our duet pleasing to us both; and we accepted each other as we were. Except for what I found his delightful, touching efforts to smooth the jagged edges of my “Texas wildness.” Those at home in Texas would have laughed at such a description of me, as I did myself.

One afternoon in mid-October, when the light had changed its angle and taken on a fall glow, even though the day was still as warm, almost, as summer, I returned to my room to find a note under my door, from my Cellist, commanding me to meet him that evening at 7, in the Arènes de Lutèce, the ancient Roman arena just across rue Monge. He said nothing about why I was to meet him there; only the command. I had learned by then that his commands were never tyrannical, that they always redounded to my pleasure. So I would go to the arena as he told me to, of course.

But I had a twinge, remembering how Clem and I had walked there so many times together in old days, had even walked hand-in-hand in the dusk, had even kissed in some of the secluded nooks, where the few others walking there were not likely to see us, especially at later hours. I wondered how it would feel, going back there without Clem, even though to meet my Cellist, fellow traveler in the new Paris life I now lived.

As 7 o’clock approached, and the sun sank behind the buildings to the west, but still flamed above them in brilliant display, I walked down rue Rollin, past the house where Descartes had lived, and down the steps at the end, to rue Monge. The traffic, at that hour, throbbed. Such a cacophony. At last, I managed to cross Monge, and, lest I be late, hurried down rue de Navarre, remembering as I hurried, another time of hurry, and worry, down these same streets – that time when I feared that I would miss Clem’s train. How long ago that seemed now. And how foolish I felt now, that I had allowed myself to worry at all about being late that time. Far better that I should never even have known that the train I rushed to meet might have been bringing my lover back to me, far better to have missed the train entirely, with no worry or regret. (Though even after all the heartache and disappointment that train had foreshadowed for me, I couldn’t even now wish that time had never happened.)

I turned into the arena gate, and looked up at the flowers lining the garden paths to left and right, chrysanthemums in clumps of fall colors, yellow, gold, rust – the colors of a more subdued Paris, accepting that the exuberance of summer must give way to the more grown-up sobriety of a coming winter, a Paris still of beauty, but with the froth of spring and effervescence of summer stilling.

As I continued through the tunnel into the arena, I heard the strains of distant music – cello, of course. Though I had not been alerted to expect it, I was not surprised to hear it now. The music grew louder as I walked on. It filled the dusk with a breathtaking beauty. I knew it to be the largo movement of Chopin’s Cello Sonata in G minor – I knew because I knew that my Cellist was working the piece up for a performance soon. As I came into the arena proper, I saw him sitting on a bench on the vast arena floor, playing his instrument, alone, no accompanist, though at the time and place, he needed no accompaniment – playing as though making love to his instrument and the music – love with a passion I could only envy, because it was a total love which he reserved for music. I would have been jealous, had I not known how right it was that he should give that engulfing love to the thing that made his life. In truth, I was jealous, a little, a petty jealousy because I wanted all of him, and all of his love for myself. Selfish and greedy perhaps I was, but not foolish too. So I was also grateful that he had even a little love left over, which he now chose – for a while at least – to give to me.

The three or four others in the arena at that hour, stood amazed and enthralled at the transcendence happening before them – almost as though miraculous in the now half-light of the coming night. Later on, how would even they believe that it had really happened, as they told of it to their families and friends? I hardly believed that it could be real myself. But then my Cellist caught my eye for a moment, and almost smiled, before he closed his eyes and gave himself fully again to the otherworldly spell of his beautiful music in the beautiful pre-night in this place from a history so ancient it seemed all but mythical.

The final strains of his music sounded through the empty arena as the light faded fully from the sky. He sat limp for a few moments, as fully spent from the love he’d been making to his instrument, as we now often were after the love we made together. Then he leaned back, and with his eyes closed, turned his face up to the night sky. I walked close up to him; he looked at me, and smiled a weary, but celestial, smile – and then stood up and put his instrument in its case, and then put his hand on my arm and nodded his head on my shoulder. I felt his thick black hair against my neck. I put my arms around him and held him close. I knew that he was making me the gift of this improbable, almost incredible, moment, and I resolved that, no matter what might happen in the future, I would always be grateful to him for it.

In a while, we walked together out of the arena, and through the dimly lit streets, across Place Monge, and to rue Mouffetard, still busy, though the market shops were making their preparations to roll up their awnings and close their doors, at the end of another day of feeding the neighborhood. The lights, gas lights and electric, gave a muted October warmth to the evening. We went into the corner café, Le Mouffetard, for our apero – we had Pernod, as had become our custom – and I looked into my Cellist’s face, watching as he drifted still in the musical world that had so recently engulfed him, and enraptured me. We were together still in that otherworldly space, even as we sat in the busy café, sipping our drinks.

My Cellist seemed to radiate an inner glow of consummation, an aura new to this evening, or one which I had not had the eyes and understanding to see before.