Song of the Amorous Frogs - Part 8

A Story of Paris in the 1920s

(The Frogs return! Catch up on their earlier adventures here: Song of the Amorous Frogs.)

XVI

By the fall, my Cellist and I had become content with each other, and the tenor of the life we led together – when we were together, which was often, but not always, since we maintained our separate residences. He was well occupied with his music study and performance, and I, with art and writing. I even hoped to see my story, inspired by the amorous frogs, in print – if only I could ever end it. And so there were times when we did not see each other for a day or two together. We both seemed to feel such separations deeply – and we both seemed to want to make them as rare as necessary. When we stayed the night together, which we did more and more as the months passed, we stayed at my room, whether because he lived with family, with roommates, with a lover, I did not know. And I did not ask; I had learned enough by then to know that some things should not be asked – if the answer might not want to be heard.

Though he sometimes seemed strung as tightly as his instrument, I learned the signs saying he needed space and time to let the tension ease, and I took control of myself enough to give the space when he needed it, not purely from concern for him, but also to be sure I would not drive him off with expectations he was not able to fulfill, or not willing to. It had come to me some time before, and some time after Clem did not return, that perhaps part of a reason might have been a truth my love forced him to see, which he was not yet strong enough to bear.

As the leaves of Madame’s trees turned golden outside my window, and fell, we found the rhythm that made the music of our duet pleasing to us both; and we accepted each other as we were. Except for what I found his delightful, touching efforts to smooth the jagged edges of my “Texas wildness.” Those at home in Texas would have laughed at such a description of me, as I did myself.

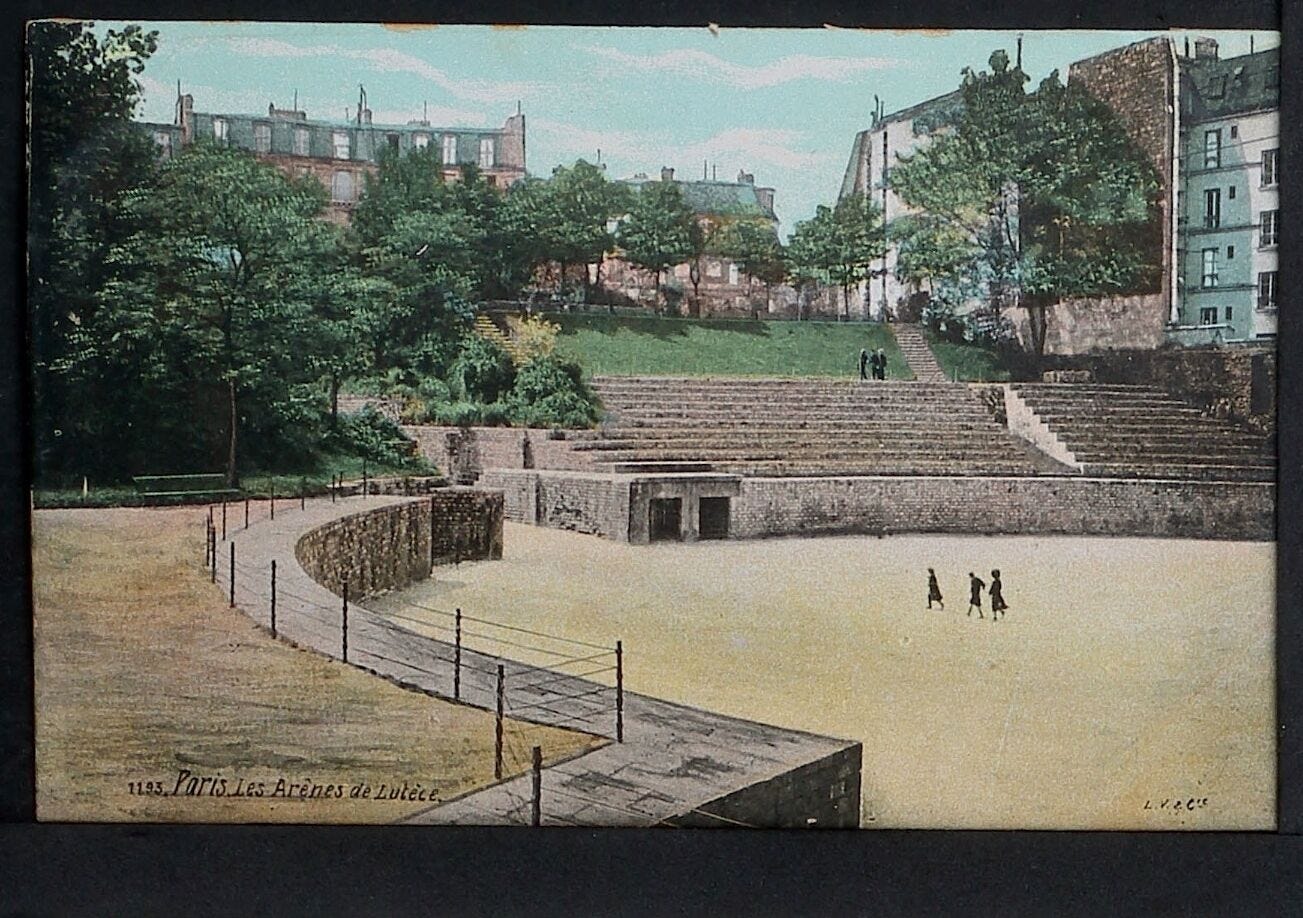

One afternoon in mid-October, when the light had changed its angle and taken on a fall glow, even though the day was still as warm, almost, as summer, I returned to my room to find a note under my door, from my Cellist, commanding me to meet him that evening at 7, in the Arènes de Lutèce, the ancient Roman arena just across rue Monge. He said nothing about why I was to meet him there; only the command. I had learned by then that his commands were never tyrannical, that they always redounded to my pleasure. So I would go to the arena as he told me to, of course.

But I had a twinge, remembering how Clem and I had walked there so many times together in old days, had even walked hand-in-hand in the dusk, had even kissed in some of the secluded nooks, where the few others walking there were not likely to see us, especially at later hours. I wondered how it would feel, going back there without Clem, even though to meet my Cellist, fellow traveler in the new Paris life I now lived.

As 7 o’clock approached, and the sun sank behind the buildings to the west, but still flamed above them in brilliant display, I walked down rue Rollin, past the house where Descartes had lived, and down the steps at the end, to rue Monge. The traffic, at that hour, throbbed. Such a cacophony. At last, I managed to cross Monge, and, lest I be late, hurried down rue de Navarre, remembering as I hurried, another time of hurry, and worry, down these same streets – that time when I feared that I would miss Clem’s train. How long ago that seemed now. And how foolish I felt now, that I had allowed myself to worry at all about being late that time. Far better that I should never even have known that the train I rushed to meet might have been bringing my lover back to me, far better to have missed the train entirely, with no worry or regret. (Though even after all the heartache and disappointment that train had foreshadowed for me, I couldn’t even now wish that time had never happened.)

I turned into the arena gate, and looked up at the flowers lining the garden paths to left and right, chrysanthemums in clumps of fall colors, yellow, gold, rust – the colors of a more subdued Paris, accepting that the exuberance of summer must give way to the more grown-up sobriety of a coming winter, a Paris still of beauty, but with the froth of spring and effervescence of summer stilling.

As I continued through the tunnel into the arena, I heard the strains of distant music – cello, of course. Though I had not been alerted to expect it, I was not surprised to hear it now. The music grew louder as I walked on. It filled the dusk with a breathtaking beauty. I knew it to be the largo movement of Chopin’s Cello Sonata in G minor – I knew because I knew that my Cellist was working the piece up for a performance soon. As I came into the arena proper, I saw him sitting on a bench on the vast arena floor, playing his instrument, alone, no accompanist, though at the time and place, he needed no accompaniment – playing as though making love to his instrument and the music – love with a passion I could only envy, because it was a total love which he reserved for music. I would have been jealous, had I not known how right it was that he should give that engulfing love to the thing that made his life. In truth, I was jealous, a little, a petty jealousy because I wanted all of him, and all of his love for myself. Selfish and greedy perhaps I was, but not foolish too. So I was also grateful that he had even a little love left over, which he now chose – for a while at least – to give to me.

The three or four others in the arena at that hour, stood amazed and enthralled at the transcendence happening before them – almost as though miraculous in the now half-light of the coming night. Later on, how would even they believe that it had really happened, as they told of it to their families and friends? I hardly believed that it could be real myself. But then my Cellist caught my eye for a moment, and almost smiled, before he closed his eyes and gave himself fully again to the otherworldly spell of his beautiful music in the beautiful pre-night in this place from a history so ancient it seemed all but mythical.

The final strains of his music sounded through the empty arena as the light faded fully from the sky. He sat limp for a few moments, as fully spent from the love he’d been making to his instrument, as we now often were after the love we made together. Then he leaned back, and with his eyes closed, turned his face up to the night sky. I walked close up to him; he looked at me, and smiled a weary, but celestial, smile – and then stood up and put his instrument in its case, and then put his hand on my arm and nodded his head on my shoulder. I felt his thick black hair against my neck. I put my arms around him and held him close. I knew that he was making me the gift of this improbable, almost incredible, moment, and I resolved that, no matter what might happen in the future, I would always be grateful to him for it.

In a while, we walked together out of the arena, and through the dimly lit streets, across Place Monge, and to rue Mouffetard, still busy, though the market shops were making their preparations to roll up their awnings and close their doors, at the end of another day of feeding the neighborhood. The lights, gas lights and electric, gave a muted October warmth to the evening. We went into the corner café, Le Mouffetard, for our apero – we had Pernod, as had become our custom – and I looked into my Cellist’s face, watching as he drifted still in the musical world that had so recently engulfed him, and enraptured me. We were together still in that otherworldly space, even as we sat in the busy café, sipping our drinks.

My Cellist seemed to radiate an inner glow of consummation, an aura new to this evening, or one which I had not had the eyes and understanding to see before.

“It was beautiful,” I said, looking at him and envying that thing – not just the music, but the whole constellation of making and feeling and interpreting and loving – that made him a true artist, and one who could – and chose to – share his transcendent artistry with me.

He said nothing, sipped his Pernod, and looked back at me with what I took to be love in his look.

In a while, we walked on to Lilane for dinner. The evening had turned chilly, and I tied my scarf around my neck, as he had shown me how to tie it: “To protect the throat,” he said, with a seriousness that only the French can give to such a phrase. “So important to protect the throat.”

As we walked across the flickering darkness of Place Monge, I took the risk and slipped my arm through his. He did not pull away, as he sometimes had, in earlier days and stronger light. We walked that way, arm-in-arm, to the door of Lilane, and almost forgot to pull apart even as we opened the door to go in. I still kept my hand on his shoulder as we went into the bright, welcoming room, where a few diners filled a few tables, even on this mid-week evening.

I had not been to Lilane in months, and, just as I had dreaded slightly going to the arena, where memories of Clem were bound to linger, I half dreaded also this return to the place where Clem and I had shared so many happy meals and evenings back when we lived in a Paris that the fates seemed to have made for us two, alone – perhaps not a real Paris, clearly not an enduring one, but one which seemed sufficient to what we both needed then. Would the poignant memories of that Paris, and that time, and that man, taint the magic of this evening with my Cellist? How could I stand it if they did?

But when Madame, still in charge of her dining room, greeted me like a dear one returning from a long journey, and showed us to the table that Clem and I had used to fill so often, she did not ask after Clem, as she had on my last visits. A glance at me, after a glance at my Cellist, let me know that she knew a new chapter of my Paris life had commenced. Monsieur Le Chef, looked out from his kitchen as we ate, as in times past, and smiled and nodded with approval as we enjoyed the delicious dishes he had made, especially for us (so it seemed that evening). So much about the visit was the same – the table, the Madame et Monsieur, the oeufs en cocotte, the langoustine ravioli, the mousse chocolat – but also, so much was different. I could not imagine wanting to return to those earlier times, that other man, even though nostalgic tears still occasionally wetted the corners of my eyes at unexpected times and places as I lived my new life in the Paris that had become the whole world to me.

I looked again at my Cellist, as he said pleasant things to the Madame about the ambiance she had created, about the wine, and about the perfect texture of the mousse. And I wiped my eye with my finger and hoped that neither the Madame nor my Cellist would see.

As always, beautifully written and magical.