An Old Man and His Memories - Part 8: How the BIG Story Ends

Looking Back at a Long Queer Life

(Note: Catch up on earlier parts of the story HERE.)

Starting stories is the easy part; ending them is hard. Even though we all really know how they’ll end from the beginning – at least how the BIG story ends – we do our damnedest not to admit it, to ourselves or others.

What possible good could all this looking backward do? None, surely, and yet we old moths fly to it anyway. A fool’s effort to weave the disparate threads of life into a whole cloth before the end – a life’s winding cloth?

Often, in those later alone days, I felt as though adrift without a compass. More Jonah than Ishmael, I did not so much long for the sea at those damp, drizzly November of the soul times, as feel that I’d been grasped by a sinister hand and flung into it. A good enough swimmer, perhaps even better than most, I’d made it far into life, had grown old, when many others had not had the chance to do so. But some days I almost wished I hadn’t either, wished the waves or the big fish had been more methodical in making an end of me. A quick painless end, ideally, though I imagine that neither drowning nor digestion would be that.

So far, the feelings had always passed before I jumped aboard the ship on that last long voyage – or jumped off it. And I felt pretty sure they always would, since, for most of us such thoughts are only melodrama. For most of us, but not all, as I had painfully learned a time or two. But for me, melodrama, surely. No cause for alarm.

But even melodrama, and pretentious references to literary classics, didn’t always make filling empty days – and nights – easy. On some of those days, like an adolescent with pimples about to pop, I felt as though I stood out for my defects, a spectacle of imperfections, with which myth says we grow comfortable as we age.

I knew I was old, mirrors and arthritic joints left no doubt of that; and I knew that I should have come to that old-person peace (or reconciliation, anyway) long before. But on those difficult days, in those old years, I struggled to do things most probably do when they are young - write a first novel, read a classic for the first time, figure out my place in the world. And struggled to do it alone.

But, NO! This simply wouldn’t do. Only an hour before, as I had walked to Sam Wah and watched the young men ahead, hand-in-hand, on West Pine, I’d had thoughts of bliss. And now, musings of lonely last voyages – whether melodrama or not.

Get up. Get out. No more of this. Perhaps a lunch at Balaban’s would help dispel my “hypos,” make me a touch less “grim about the mouth.”

I picked up the stack of checks to be mailed and took them down to the lobby. Perhaps I hadn’t already missed the postman. Though I wrote the checks so promptly – another of my old-man quirks – I had no real reason to hurry getting them mailed.

Writing the checks had been one of my jobs in our three-way division of domestic labors, almost since the moment I joined the household. Our Cellist had been hopeless at it, and even Clem, a man of business, though “retired,” could blithely write a check without even a glance to be sure the account would cover it. I even wrote the checks on those rare occasions when I went away alone. Wrote them, and left explicit instructions as to when they must be mailed.

Instructions not always followed, as I found when I took my first such solo adventure (until then), to Houston, in ’53. The by then world-famous Tennessee would be there directing someone else’s play, a first for him (The Starless Air, by his friend and sometime collaborator, Donald Windham), at the Playhouse Theatre, the Main Street venue created by Joanna Albus, protégé and close friend of Margo in earlier days – though in those earlier days she’d used a different name, a character still in process of creating herself – as were we all – then, and I supposed, always.

Tenn invited me to be his guest and guide. Though I would be a guide in need of guiding, since it had been almost 10 years that I’d been away.

I went alone. Clem had no interest. Our Cellist might have enjoyed seeing this new part of America – provided we added a day or two in “Nouvelle-Orléans.” But in the end, his performance schedule did not have room for even a short trip, so I went alone.

Just as well. Houston was no longer the city I remembered, and sometimes had the wistful thought I might return to – especially in those years when the snow piled high along West Pine, and the cold wind blew straight down from the Arctic.

I wouldn’t return, of course, for anything more than a visit. What was there to warm me now in Houston, aside from the sun? Certainly little to warm the soul. By then my soul-sun shown in St. Louis. That became clear in just a day or two. And I went back north with no regrets.

Over the years I heard that many had gone: Mrs. Cherry at 95 (1859-1954), from the rigors of a long successful life; Margo at 44 (1911-1955) from kidney failure, poisoned by a lethal mix of alcohol (the hard drinking kind) and carbon tetrachloride, the one from partying, the other from carpet cleaning, together a fatal cocktail; Lorin at 51 (1918-1969), from who knew what, perhaps the crushing of hopes and dreams of one stout enough to survive San Quentin, but too fragile in the end, to survive the world. Others gone from my life, if not the world, but not gone from memory: Gene, Cardy, Forrest, Russell – more and more. Going seemed to be on the to-do list of so many as the years passed.

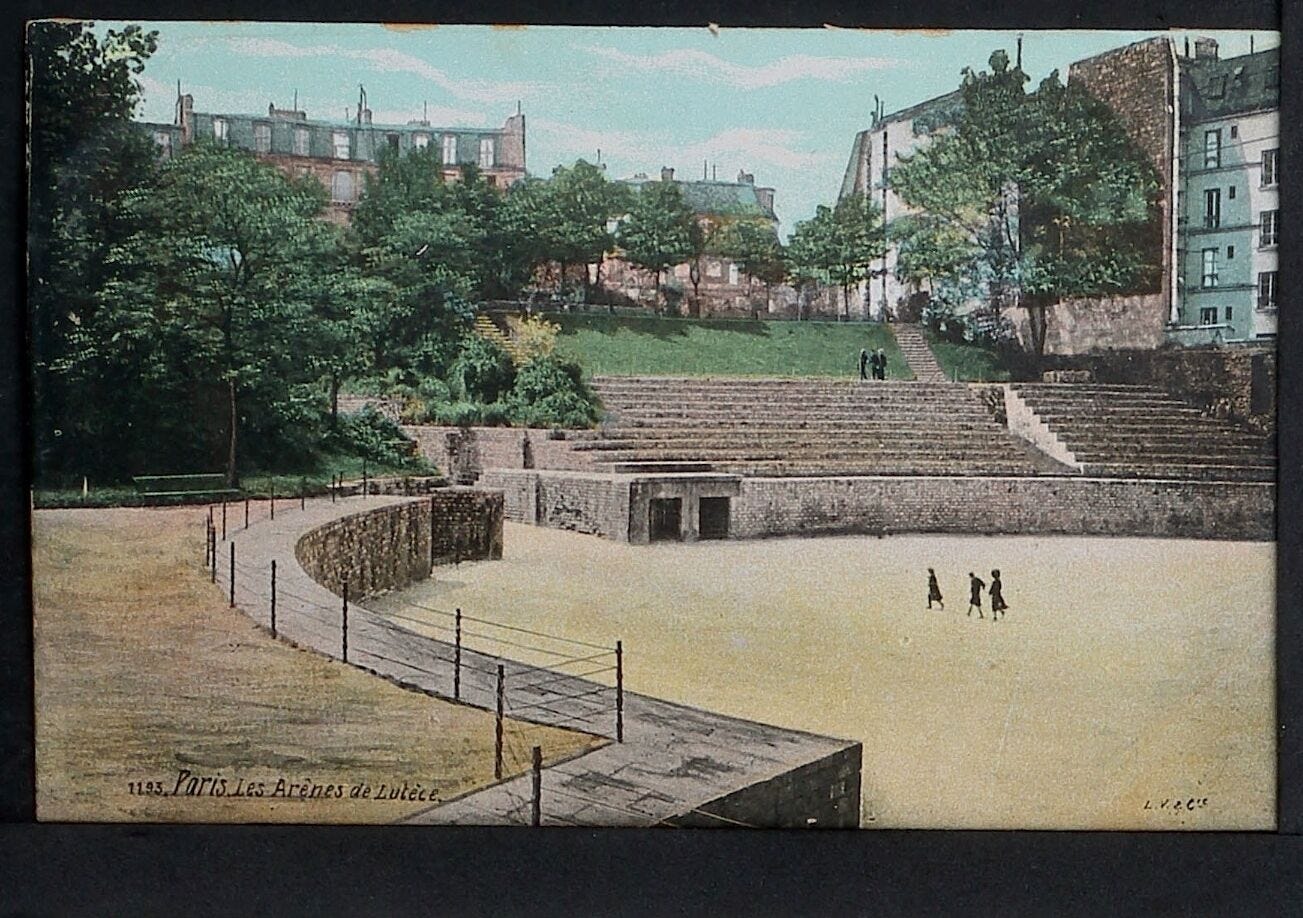

Then the great tragedy of the great loves gone. First Our Cellist. Clem and I took his ashes back to Paris, as he’d asked. We took him with us to revisit the places we’d first known together so long ago. To Café Gaudeamus (now gone), where our table in the back did at last have room enough for three. To the garden of the Madame, her garden still beautiful, but now gone herself. To the Arena, where we all remembered his beautiful music. We left him there.

Soon, back in St. Louis, Clem gone too. His family took him to the family tomb in Chicago. At their request – their insistence – I stayed away – cried my goodbye tears alone.

And then I was again only one, as I had been at the beginning.

As I locked my door, I saw my new neighbor unlocking his – to one of the studios we three had made ours while we still were three. There had been no reason for me to keep it – or the one beside it. One apartment now seemed almost too big. And so I had let the others go.

I knew that someone had moved in. Jimmy had told me that, though he knew little more to pass on. What a surprise now to see this new neighbor – the young reader from Habs House. My heart raced a little when I recognized him. And my cheeks turned a little pink, as though I’d been caught in my clandestine watching. I went down in the elevator wondering what the cosmic forces might be trying to tell me with this improbable coincidence.

By the time I reached the lobby, I felt a little dizzy, a little out of breath. I put the envelopes in the collection box – all but the one for Bissinger’s – I’d deliver it by hand on my way to lunch.

I waved to Jimmy, standing sentinel at his desk by the door.

“I saw my neighbor,” I said.

“Yes, sir, he has moved in. Such a young man, and polite. Perhaps like you when you were young?” and we chuckled.

When I was young, I thought. When I was young.

I sat down in the chair by the window, where I’d sat not so long before. Sat, to catch my breath a bit before I walked up Euclid to McPherson, to Bissinger’s and Balaban’s. Sat to think back a little to those days when I was young, and all the days that had been my life between then and now, all the places and people. Old moth to the flame of remembering. I took a deep breath, and propped my elbow on the awkward chair arm and rested my forehead in my hand. I closed my eyes – they watered a little – perhaps allergic to the spring pollen.

No need to hurry to lunch. I had all afternoon. And no one else would want the chair. I felt weary. Perhaps more weary than I’d ever felt before – as we sometimes say. Though who can remember all their weary times to know that’s true? Weary enough, anyway. It would do.

Maybe I’d take the time for a little doze. Why not. I had all afternoon. And the checks were written and mailed. And no one would be awaiting my arrival, either eager or impatient. And as the breeze gently lifted the white curtains into the room, the memories might almost transform into dreams …

“Old moth to the flame of remembering.” I can see it. I have fluttered there myself.