Song of the Amorous Frogs - Part 9

A Story of Paris in the 1920s

(The Frogs return! Catch up on their earlier adventures here: Song of the Amorous Frogs.)

XVII

A few days later, as my Cellist prepared to leave my room above the garden (I had almost begun to think of it as “our” room once again, though the thought still sparked a hint of superstitious unease), he said, “This evening we will go to a special performance. Everyone is going and talking about it. Cocteau mentioned it with high praise and wonder. For you it will be particularly special, since the performer is one of your people – a man-magician, so they say, from your Texas.”

He now often referred to it as “your Texas,” when he wished to make the point that he took into account my distinctive origin, and its continued, somewhat perplexing, importance in his image of me, even as he worked to infuse a refining French-ness into me - just as he referred to himself as “your Cellist,” to acknowledge, and at the same time belie with his tone, my persistence in calling him “my Cellist.”

I had, in fact, begun to develop, and share with him, a small circle of fellow Texans-in-Paris, that included Miss Bonner of San Antonio (Mary), a printmaker of growing acclaim, in the city studying with the French print master, Édouard Henri Léon. She lived not far away, in rue Notre Dame des Champs. And also Watson Neyland and Miss Margaret Brisbine, both students of John Clark Tidden, painter, and teacher of drawing at Rice Institute (with whom I had also studied, though as a private student, not at the Institute). They both came to Paris, from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, thanks to the Cresson Travel Fellowship awarded to each in different years. Miss Bonner, with her prints of Texas Cowboys, exhibited to great fanfare in the Salon d’Autonme, and Miss Brisbine, with her portraits, both made a stir, and not just among the many Americans then in Paris, but also among the French. Neyland, who tended to drink too much, and did not stay long, made less impression. And Mr. Tidden himself stopped off in Paris, on the way to Italy, summer students in tow, and I met him for a dinner and evening of news directly from home.

But I knew my Cellist could be referring to none of them; they were not “performers.” And so I had no idea of whom he talked.

“You will see. Be ready to depart at 8. I will come for you, and then we will go to Montmartre – to Casino de Paris. We will be enthralled and amazed, so Cocteau says.”

And, indeed, Cocteau had much to say about the “enthralling” Barbette – as this wonder from “my Texas” was called – when we encountered him as we arrived at Casino de Paris. Immediately, he turned effusive – as he often did, always so excited about the wonders Paris offered up to those perceptive enough to be open to them. Barbette was “no mere acrobat in women’s clothes,” Cocteau exclaimed, gesturing expansively to be sure that all who heard him knew how indisputably true his judgment was – and he intended that all within earshot would hear, not just those of us he addressed directly. “Nor just a graceful daredevil, but one of the most beautiful things in the theatre. Stravinsky, Auric, poets, painters, and I myself have seen no comparable display of artistry on the stage since Nijinsky. Ten unforgettable minutes. A theatrical masterpiece. An angel, a flower, a bird.”

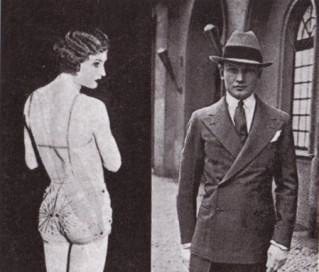

The program told me that this wonder did, indeed, come from Texas – Round Rock – and that his name when not on stage, when not the incredible Barbette, was Vander Clyde Broadway. I learned later that he had made his way from Round Rock, through New York and London, to Paris as a female-dressing trapeze performer. But in Paris, the city where ordinary life had no place, where all life was extraordinary, he had become simply BARBETTE, and needed no other name for all doors to open before him. The persona that would have made matrons – and possibly some men too – blush in Texas, made all Paris swoon. It was said even – said by Barbette him/herself, when we met after the performance – that one Parisian journalist had “walked unannounced into my hotel room one day, obviously hoping to find something unimaginable.” And Barbette was unimaginable as part of the Texas I knew from growing up there – just as my own Paris life was unimaginable there.

What we saw, in the packed Casino de Paris, where the enthusiastic – one might say enthralled and mesmerized – crowd had little need for seats since they were on their feet almost the entire time Barbette performed, exemplified the difference between mere performance and artistry. Barbette, though a character created by the man, Vander Clyde, embodied an illusion of the feminine coming deep from the psyches of artist and viewer working together to make a something that did not exist in life, though all wanted it to exist in some realm – agreeing, from a need more than titillation. Each gesture, each subtle, seductive swivel of the hips, each glance over shoulder from sultry, melancholy eyes, suggesting the insubstantial substance of things hoped for, the elusive evidence of things not seen. The swoops back and forth on the trapeze, like a female angel fluttering above – if such a creature existed. It hardly seemed possible that such a marvel could have been created from the mind – from the being – of a fay man from Round Rock, Texas, and so Barbette must be the latter day creation of whatever divinity had made Adam and Eve in long-ago days – but now, making them one in the body of the captivating Barbette. The 10 minutes in which Barbette/Vander Clyde dazzled and beguiled us flashed by as though an instant, and we had that rare experience in a theatre of being transported to some other world entirely. With Barbette’s final flawless gesture, our applause erupted, and we stood as one, cheering, almost unable to breathe, and some with tears in our eyes.

Very late that night, after the performance, and after the café, where Barbette and Cocteau had both sparkled like stars from their own rarefied Milky Way, when my Cellist and I had made our way back across the Seine to the other bank, and our usual life, and made love, which was never “usual,” in these still early days, he seemed to look at me with a new respect (or was it, slightly, envy) that I came from the same faraway land as this “Barbette,” who had become the Toast of Paris. And I delighted in this chance to bask in a Texas glow, that had gained a new attractiveness for this beautiful man I so longed to attract. I thought a few words of thanks to the illusory Barbette, of whose existence I had not even known a few hours before. And I kissed my Cellist on the lips, and held him as we drifted into sleep.

XVIII

In winter, Paris turns chilly and damp, with drizzly rain for at least parts of most days, and with grey skies, no longer a paradise of warm, golden glow. Perfect atmosphere for lingering over strong coffees in warm (if smoky) cafes, and for fondue and raclette and tartiflette in the Savoyard restaurants along rue Mouffetard – dishes unthinkable for the summer, but indispensable to soothing souls and psyches left bereft of comfort by the bleak season, dimming the light in this City of Light.

Though drinking my Pernod, and eating my dinners of mountain cheeses, and then walking the few blocks to my room, which Madame made sure welcomed her cold lodgers back from city forays with ample heat from the clanking radiators – doing these winter things with my Cellist beside me made this winter a soul-gratifying joy, compared to the lonely, dissolute winter of the year before.

My Cellist even seemed almost to open like a winter flower – not flamboyant in blossoming, witch hazel or winter jasmine, hardy enough to withstand the wintry elements, and flourish.

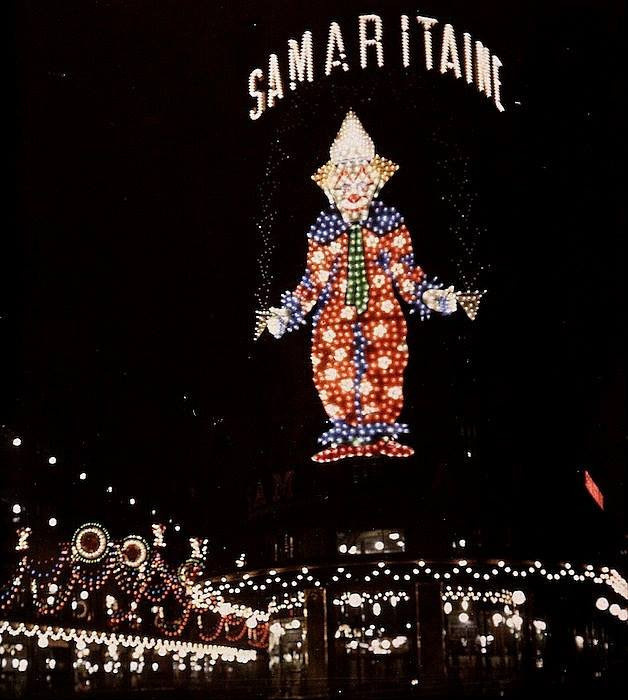

He took me to see the Christmas windows at La Samaritaine, with automaton children tucked into their lit-clos, dreaming of sugar plums, beside Christmas trees aglitter with candles and silver icicles; and Printemps, so ironic and unlike spring, bedecked with snow-white flocked pines, and parties of mannequin-lovers, gliding on skates across winter lakes of mirrors. And to the Alsatian stalls de Noël, opened near the Gare de l’Est for those unable or unwilling to make the journey to Alsace itself, and to emphasize, even at this time of holiday festivity, that the region, only recently wrested back from the Germans at the end of the Great War, was indeed now a part of France.

As Christmas day approached, I felt a bit low that I would not be with my family and friends in Houston another year. But I would be with my Cellist – at least I supposed I would – which made ample compensation for the absence of family. Not that I loved them less, but I had long since begun to love him more – with a different love, but a love that swept all other loves aside – at least for now. Did he have that love for me as well? It was not a question I could, or dared to, ask him, in case he answered in a way I did not want to hear – and could not stand to hear, so I thought in my own conflagration of love. There might be time enough for that unwanted question, for some unwanted answer, in the future. But, not courageous enough for a devastating truth, I worked hard to put off the day when it might unavoidably come due, for as long as could be. The day might never have to come, after all, so why not be timid instead of bold about such a fraught asking-and-answering? It sufficed, for now, that I loved. And that he might.