Song of the Amorous Frogs - Part 7

A Story of Paris in the 1920s

(The Frogs return! Catch up on their earlier adventures here: Song of the Amorous Frogs.)

XIV

As I approached Café Gaudeamus and looked through the window, before pushing through the door, I didn’t see my Cellist. The dreadful chill of disappointment sickened me. I reminded myself how I knew all along that he would not be there. Had I learned nothing of the ways of the world by now? I almost turned to walk back down the hill.

It was too early for the Bal Musette, but perhaps not so for a dinner of entrecôte, served in the subterranean depths of L’Ecurie on the corner of rue Laplace – accompanied by a mountain of frites and a heaped bowl of aioli, which migrated from table to table as the need arose - all served by the “hunchback of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont,” with his limp, and his Prince Valiant hair to his shoulders – so I thought of him this evening as I let the bitter disappointment fill me with spite. I thought, also, how foolish I’d been, not to have gone up to Clem, even if only for a night. One night would have been better than none, with only a likely tough steak for consolation after being stood up.

But then I saw him, sitting in a back corner of the café, his instrument in its case leaning against the wall. He looked around with a somber expression on his beautiful, pale face – perhaps expecting that he would be stood up too? Perhaps thinking how foolish he too was, not to be keeping an appointment set by some Clem of his own, instead of sitting alone in a café, waiting for a passing fancy whose time might already have passed. Perhaps grappling (both of us) to accept that there were many Clems in the world we were entering.

Or maybe he was thinking none of that – just half irritated that he’d made an effort, and got there early, only to be kept waiting by an unreliable American. But whatever he might (or might not) have been thinking, when I went through the door, and when he saw me, he smiled and nodded, and I smiled and nodded. And we entered this new realm of possibility, together.

“And so we have both kept our assignation,” he said, in his precise English-accented English, and with a light turn of his head and lifting of his black eyebrows. “This is a good sign for a long and happy life together,” and his faint smile on his pursed lips made clear that he spoke to be amusing, and amused. “Therefore, you may sit and join me.”

“How kind you are, to permit me,” I replied, as I sat in the chair he indicated.

“Yes, usually I am not so kind. Most cruel. I make an exception for you. I have a softness for young Americans of a certain beauty. Though not always a softness.”

I smiled at the suggestive possibilities of his banter, not sure if he knew how his phrase, in English, might be understood in the argot of some circles in England and America. Then the gleam in his eye, and the wry smile on his lips told me that he did know, and that he intended just such an understanding.

“Then you intend to make me your plaything?” I asked, joining him in a back and forth that had become familiar to me over the last months, but one that was not often so piquantly amusing with most, as I was finding it with him.

“As a cat does a mouse,” he retorted instantly. “And one of us, at least, will have great fun in the playing – until it is time for it to end, as such playings always must. And then, poor mouse.”

I could no longer maintain the mock-serious mask we’d tacitly agreed should accompany our gripping little comic opera. I smiled broadly at him, and said, “Yes, poor mouse,” and arched my own brow, and hoped my attempt at wit, to match his own, would not disappoint.

The cock of his head, and his appraising eye – and then a slight, tight smile on his enticing lips suggested success for my sortie – for this moment, at least – which was enough – for now.

“We will continue this after I play,” he said. “You will be there …” (it was not a question) “… and then after, we will have a supper, and then we will continue this. I am not expected a ma maison ce soir.”

And with that, there were no more questions to be asked and answered about what the evening (and the night) ahead would hold. And this new age of possibilities seemed to have launched, with vigor.

I did accompany him to hear him play as he had commanded, of course. The same trio of musicians, again in Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, but this night they played Debussy, a dissolving, lyrical magic carpet of music that transported me even more fully into the mesmerizing spell he cast over me with his artistry.

The next morning we stayed in my room overlooking Madame’s garden until well past 10. He had to hurry then, or be late to his class at the music conservatory where he studied (and also taught some of the younger musicians). For that, he would not be late. I watched from my window as he came out the door from the stair, into the garden, carrying his instrument in its case, against his shoulder. He passed Madame, as she came up the carriageway, carrying her marketing in net bags. She had been to Place Monge, and she had, without doubt, picked the best of each thing she chose.

“Bonjour, Madame,” he said, with a self-assurance that left no doubt as to the legitimacy in his being there, at that hour. “How is the white asparagus today?” he asked in his precise English. He spoke in English so that I could understand him, and know how confident and in control of all situations he was. “I must have some, if it is fine.”

“Indeed,” replied Madame, not revealing the least surprise at the presence of this stranger with a cello in her garden at such an hour – glancing, in fact, up at my window, as she said again, “Indeed.” And then, “It is fine. You must have some.”

I heard my cellist reply, “Then I shall!” as he hurried into the street.

Madame looked again toward my window. I nodded – and we both smiled.

XV

Thus began this new chapter in my Paris life, so unlike that I’d lived with Clem, that it was as though someone else had lived it, not me, and in some other universe. My Cellist, only a year or two younger then I, seemed so much younger in spirit. Either he had not yet been disappointed, or – more likely – he had a perhaps Gallic talent for leaving disappointments in the past.

And he was not content that we should be a universe of two. He knew everyone, it seemed, in the fevered world of Paris music and art, especially those of whatever nationality, who found in Paris a place where they could make their art without restraints, no matter how queer the art, or the world they constructed so that they’d have a fertile, and safe, milieu in which to make it – for most of them, so unlike what they had left behind, in native lands.

Like Pygmalion, he seemed to see the need to shape me for the higher life he intended we should live together for as long as our “playing” lasted. I felt no need to resist his shaping.

He began by taking me to an exhibition of new paintings by an artist I did not know, a woman “working in the modern mode … but in a way so different from those men, Picasso and the like.” A woman named Marie Laurencin, showing at Galerie Paul Rosenberg – paintings of a world of women, without men, almost unnerving in their frank femininity, sufficient in itself – just as ours was, in some respects, a world of men without women, a world of the frankly masculine that could embrace a feminine element in itself, which most men seemed afraid to grasp.

And then on to a hotel in the rue Jacob, temporary home and studio, to a Russian just arrived in Paris, Pavel Tchelitchew, fleeing the aftermath of revolution in his native Russia – as so many Russians in the city were – and fleeing, also, the constraints on men like him – and like my Cellist and me – which even the revolution had not loosened.

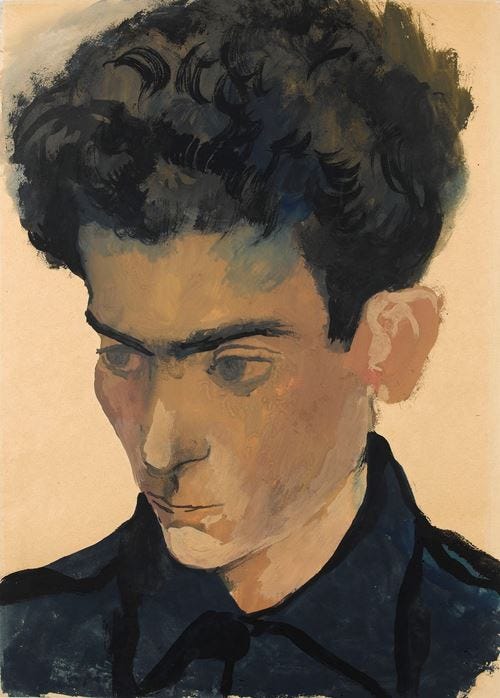

“He is doing my portrait,” my Cellist said, with pride, though with a tone that he intended should make the pride imperceptible. “Doing it very well, the likeness, and will show it at a gallery when he is done. I will be celebrated by all Paris, and not only for my music, as now.” He smiled, not modestly, but with the confidence that one day he would be celebrated by all Paris. “Inévitablement.”

Pavel – he insisted I call him that, even though his manner seemed very formal – very Russian, it could have been, and thus completely unfamiliar to me, since I had met no Russians before – that I knew of – Pavel showed us the portrait, finished to my eye, though perhaps not quite finished to his, since he had yet to sign, or title, it. But it was indeed a good likeness; it was my Cellist to the soul – literally to the soul in a way that few portraits – even none at all – I’d seen before, achieved. I had no doubt that it would someday make both artist and subject “celebrated by all Paris.”

He had only recently come to Paris from Berlin, with his close friend, a pianist, Allen Tanner, to see if a more permanent stay in the city, the center of the art world, might offer promise of a wider audience to laude what he knew to be his genius. Tanner, it turned out, had ties to Chicago, and so I asked if he knew Clem; and, it turned out, he did – though he said nothing more to indicate the nature of the “knowing,” and I asked no further questions.

Because of his Chicago connection, I mentioned my neighbors, Ernest and Hadley. Pavel said that they had met them “only the other evening,” on a visit to the salon of a monumental American woman, in the apartment she shared with another (not so monumental) American woman, in the rue de Fleurus – an apartment filled with art, including “the portrait of Gerturde, by Picasso himself.” And also chair cushions “stitched by Alice, to designs Picasso had done for them, specifically.” Picasso had not been at the salon that evening, but Gertrude had said – in her rather modern way – that she would introduce him “with gladness” the next time they both attended.

“This will be a great help,” Pavel said, confidently suggesting by his manner that the help would not flow in only one direction.

After a time of looking at – admiring, rather, is the more accurate term, and the one expected – Pavel’s paintings and drawings – some, of men entwined with each other, so shockingly explicit that I blushed seeing them, and my heart raced; these shown seldom, he said, and then only to “certain” men – we all went to a café in rue Jacob where we spent some considerable time drinking and talking, my Cellist and Tanner, about the advanced new music in the city, Pavel and I, about the art, which Pavel said needed “change and renewal. I will be one of those renewing it.”

Later, as my Cellist and I walked through the streets of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, on our way back to my room above Madame’s garden, on our way to another supper and evening together – he did not play this evening – I thought about how different it was, this Paris I’d been discovering with him, than the hermit-Paris I’d known with Clem, or even than the “debauched” one I’d known alone. And I thought about how much more exciting this Paris was than either of those I’d known before. And how I hoped it would be the one I’d be able to feast on far into the future. I thought this even as the demon of doubt whispered that only fools let such thoughts, and hopes, of “future” linger in their minds.