Song of the Amorous Frogs – Part 12

A Story of Paris in the 1920s

(The Frogs return! Catch up on their earlier adventures here: Song of the Amorous Frogs.)

XXII

In late October I had a note from Mrs. Cherry: “I have received an unexpected windfall – a check from home – oil royalties! We shall all go for a ‘spree’ – on Saturday, if you and your Cellist are free. Clemmie Tan will join us. You will meet her at last!”

At last, indeed. It seemed that I had been hearing the name, Clemmie Tan, so long that we should be old friends. Mrs. Cherry spoke of her every time we met – half a dozen times, by now, since they had arrived in Paris. And yet for one reason or another she never could be with us. Now, it appeared, she would be.

I knew Mrs. Cherry to be a long-married – and happily so, one supposed – woman with a daughter, an unconventional woman in some ways, as she said, but one conventional enough in that way to secure her place toward the top of the diminutive social and artistic world of Houston. And Clemmie Tan, as Mrs. Cherry had described her, was a new bride longing to be with her husband as soon as his research in Russia, and her study in Paris, would allow. So neither was a woman-loving woman of the Natalie Barney sort (one supposed). Still, the admiration and bond between them went far beyond the usual bonds of mere friendship – not that “mere friendship” was a thing to be scorned – even between women, who seem to bond more readily than men. Their friendship did not fit the pattern I had come to understand and expect, in Paris. But since Mrs. Cherry expressed no judgements about my friendship with my Cellist (or Clem either, for the little we touched on it), only acceptance, I would not judge, or even scrutinize too closely, hers with her Clemmie.

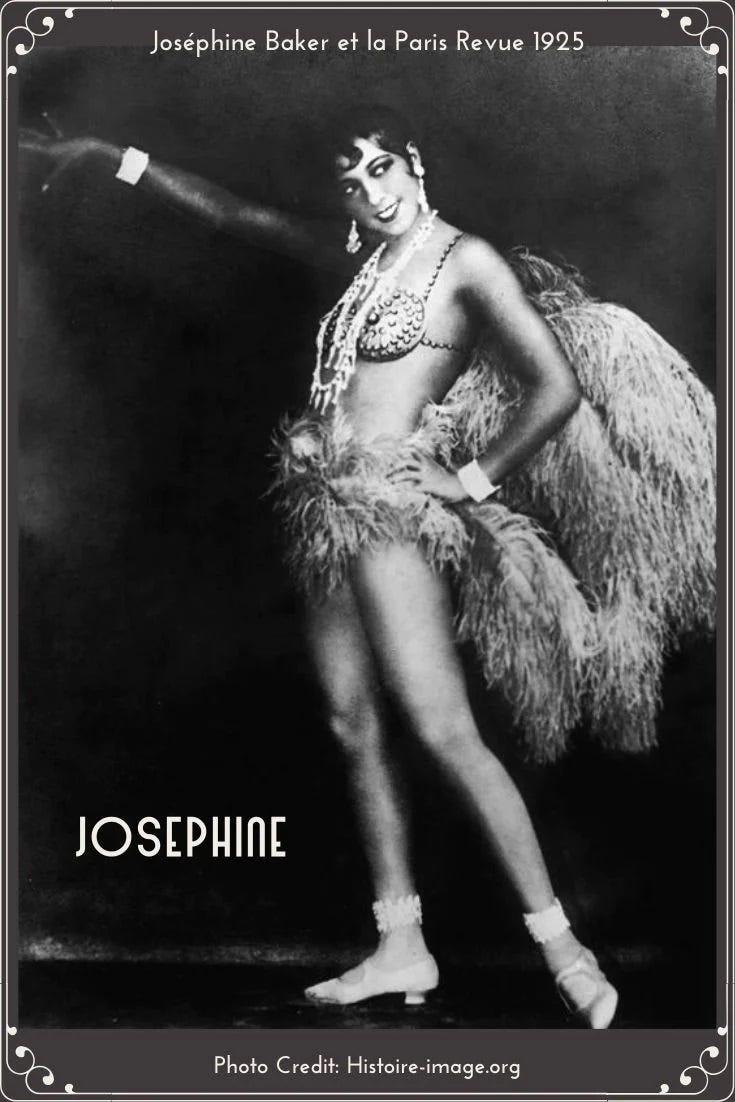

At Mrs. Cherry’s invitation, we were all to go to see the latest theatrical sensation from America (the latest, now that Barbette had been embraced by Paris and become Parisian in Gallic eyes), an exotic extravaganza called La Revue Nègre, from New York, playing for a month already at the new, modern Théâtre des Champs-Élysées – the sensation of the season for fall 1925. Paris always craved, and always seemed to find, a new “sensation” every season.

And as Barbette, of Round Rock, Texas, had personified that sensation in 1923, a young black woman, of St. Louis (though I had never heard of her during my time there), did so in 1925: Josephine Baker, who would become the Toast, not just of Paris, but of all France. “She is almost a contortionist and she certainly uses the suggestions to the limit,” Mrs. Cherry said, with her piquant laugh. She had seen the show once already.

Before the theater, we went to Gallerie Bing, to see the work of Modigliani. “One of the most modern modernists,” as Mrs. Cherry said. “I had seen some of his in Philadelphia in Dr. Barnes’s marvelous collection of modernist things – so was somewhat prepared; but you may find that you are absolutely overcome!”

And between gallery and theater, dinner at a small café - of tête de veau – omelette aux herbes – escarole salad and pommes Chateaux (buttered & browned in the oven) and glasses of beer! “We’ll drink the beer in Brook’s – Mr. Cherry’s – honor, since prohibition means he cannot drink one in Houston,” she explained for the benefit of my Cellist, who might be unaware of such a strange, unnatural (to the French) thing as prohibition.

And then the theater. An evening to remember – a sensation indeed, watching Baker dance her ‘Danse Sauvage’ wearing only her skirt of feathers (those would soon be replaced with the more suggestive bananas) for an ecstatic Paris. But it was not until after the performance that the true sensation of the evening came. That came as we walked out of the theater, onto the sidewalk, laughing and happy, slightly scandalized, perhaps, at such goings on in such a venue – but it was Paris!

As we came out the far left door, onto the sidewalk running in front of the theater, I looked down the street where hundreds of others emerged from other doors, from their evening of entertainment and titillation. And among the hundreds I saw Clem!

I started, and looked again to be sure. I’d been seeing him for years now, all over Paris, when he wasn’t actually there. And I thought at first that once again it was only a similarity of walk, a tilt of head, a close color of hair that deceived me into thinking this stranger was Clem.

But this time there was no mistake. This time it was Clem. I knew, because this time the stranger looked back, and the light of recognition filled his face, and after a moment for his own shock to pass and be replaced by a smile, he gave a nod of the head I knew by heart from seeing it so many times in those past days. I felt almost faint, felt the breath knocked out of me. By the time I’d recovered enough to have even the slightest presence of mind, he’d come over to us, and taken my hand, and put his hand on my shoulder, all at his own initiative. It was as though I was there only so that he could.

“What a surprise!” he said. Such an understatement. “I’ve been meaning to hunt you down. Hadley told me you were still here. I saw them at Le Dôme weeks ago. But I’ve been so busy since I came back, getting our office opened. Father finally agreed that we needed an office in Paris. You can bet I encouraged him to it. And I convinced him I was the only one to fill it. So here I am, back in Paris. And here I’ll stay, this time.”

I introduced him to Mrs. Cherry and Clemmie Tan. We shook our heads in wonder at the similarity of names. And then he said, “Who’s this?” turning to my Cellist. “I’m Clem,” and he put out his hand to shake.

My Cellist shook the offered hand, nodded his head, his lips in a pursed smile. He was, as ever with newly encountered strangers, especially brash Americans, reserved, French. He said little that might give a hint of his thoughts, but a look I noticed in his eye made me uneasy.

Since the evening had grown chilly, and late, we said good-bye. Clem said, “I’ll be in touch. I want to visit La Madame soon.” And he gave his card to each of us, with the invitation to “look him up.” And, of course, we smiled and said we would. And then we all departed in our various directions, in ones or twos. My Cellist and I would go back to my room above Madame’s garden together. And still I felt uneasy.

XXIII

(If I asked him would he like it. Would he like it if I asked him.)

“How silly you are,” my Cellist said, when I asked him to help me understand why things seemed to have changed between us. I did not accuse and I did not rail. I did not even beg, though only a Herculean effort kept me from it. Once again my Cellist had not been with me through a long, dark night. But this time I knew who he had been with, and knew – or thought I knew – what doing.

“Silly.”

It hurt that he chose that word. There had been a time when he chose less cutting, dismissive words, even when he intended to dismiss my concerns as unnecessary, unimportant. This time, his word and his gesture left me feeling as though alone in a stark room, after love had left.

“We knew it would not last forever. Such things never do. They are not marriage. Two men do not have marriage. Two men have only our pleasures. We agreed at the start that it would last as long as it did, and then be over.”

I did not remember agreeing – and I did not like it. But what I liked or did not like seemed irrelevant, unimportant now, indeed.

My Cellist had met me at Gaudeamus, joined me at our table, as I asked, but he made clear as he sat down that he had only moments – that he must be off to his lesson soon. He did not have his cello with him, and the thought passed through my mind, Where is it?, but passed on without being asked: I knew.

It had been a month almost since our thrilling evening at Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. There had been many nights over the month that my Cellist had not been with me. More than I cared to count, or remember. And the nights when he had been with me were different. I could no longer pretend they were not. It had taken me the month to summon courage enough, to grow desperate enough, to ask him why. Though even I knew it was silly to do so; the answer to such a question is often untruthful, and never satisfies even when the truth. So how could I quibble at his choosing “silly,” but how it hurt.

“I will not be coming back to your room at the Madame’s, when you act this way. I am not your sex slave and I am not your mari, and nor you mine. And so this will be the end unless we can agree as we did at the beginning. Each must be free. Such things only last with freedom. But I fear you will not be reasonable and agree thus.”

My silence told him that I would not, could not, agree to what I had never agreed to at the start. By now I could not rewrite the terms of my love for him; not even a writer with the skills of Shakespeare could have done that. Because my love for him – for “us” – had changed only in growing deeper.

After a while, as we sat looking at each other, a minute that seemed an hour, he sat up straight and pulled back, away, and said, “And so we will say Goodbye. We have good memories, and those are all that last in this cat-and-mouse.”

He stood and walked across crowded Gaudeamus, to the door, and out. Then left, up the street toward Saint-Étienne-du-Mont and the Pantheon. I watched him from inside the café, through the window. Whether he would go into the church I could not know. But I thought perhaps he would, not to play – he did not have his cello – but perhaps to meet someone who was waiting for him there, in the precious serenity and comfort of the sanctuary, empty (in my imagining) on a weekday evening, except for them. I had joined him in that sanctuary in past days, and also Clem, and I longed to be the one joining them there again. But I was not.

After a while I walked slowly alone, past the church – I did not look in – back to my empty room above Madame’s precious leafless garden.

I love that St. Louis woman!