Left Bank on the Bayou - Russell Arrives

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

One hot, sunny morning in June I took a letter with a Santa Fe postmark out of my letter box. My heart raced when I saw the mark. It wasn’t that Russell had not written before. He had done, many times since our until-we-meet-again farewell the summer before. We had even talked on the telephone a time or two (to be exact, two; I remembered precisely; why be coy?).

But as the months passed, and only letters made the journey from Santa Fe to Houston, I began to fear that the next one might bring the message I so dreaded – that he would not be making the journey himself.

And so I opened this most recent letter with dread as well as hope. I opened it after a long while of sitting at my writing desk holding it, looking at my name in the address, his name in the return, and out the window at the garden (needing attention after the storm the night before, which had struck with wind, howlings of wind, and rain, lashings of rain), and then back again at the envelope. Finally I slipped my letter opener under the flap and slit it open slowly, carefully.

For all my reluctance, he wasted no time. The first line read: “I arrive on Thursday.”

Only four days off – and my birthday! I could not help myself but to think that his long-anticipated, longed for, arrival now about to become reality must be a cosmic birthday gift given as acknowledgment and reward for my patient certainty that he would come to me in the “fullness of time.” (I had long ago convinced myself that Lorin – Oh, sweet Lorin – had not threatened that faithful devotion to an idea of a life with Russell.)

Still, I knew that a summer fling in Santa Fe, followed by a dozen letters over a few months, and two (precisely) telephone calls hardly made a solid foundation for the dreams of partnered bliss I nourished. Some might have called me foolish for flirting with such fantasies. I’d have called those others foolish for the same fantasies – if they’d been foolish enough to ask my opinion. I knew better by now than to ask anyone’s opinion about such foolishness of the heart – even the opinion of my own worldly-wise self. I knew enough of the world (and myself) to know that wisdom is the death of giddy love, and giddy love was what I wanted, for a while, at least. For as long as I could make it last.

“One day at a time,” to use the phrase I’d heard so often during my last, discouraging months in New York, repeated by an irritating reformed drunk named Bill. Well-meaning, yes, but no less irritating even though I knew that he tried to help me ease my pain, and that he was right. And so I repeated his phrase to myself as I tried to believe in this fantasy life, even though I knew I warped the true intent of his wise words as I mouthed them.

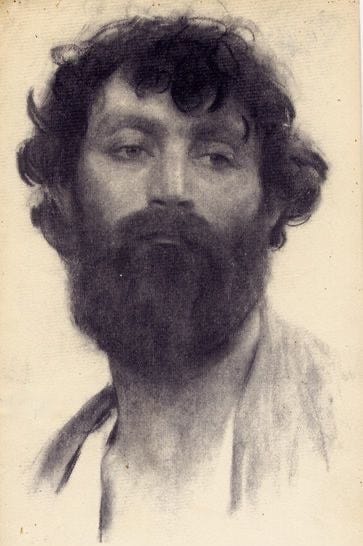

I looked at the self-portrait drawing Russell had given me in lieu of a photograph – with the thick, dark curly hair, the full beard and mustache, the eyes of the warmest depth, not melancholy or even pensive, but deep, seeing a world so much more real (and solitary) than this real world we all share. I hoped that I might soon be sharing with him the world that those eyes saw.

When the day arrived, I rose early and rushed to Union Station – rushed even though a short distance (a fact that had changed Quality Hill forever when the station had been built decades before) – rushed just as I had done all those years ago, when I made my way across Paris and through the Jardin des Plantes – and heard the Song of the Amorous Frogs for the first time – to meet Clem’s train from Toulouse at the Gare d’Austerlitz, determined not to be late in case his train should arrive early.

That day, I had been crushed with disappointment when Clem did not return, though I’d held out hope as long afterwords as I could that he still might come back. This day I hoped would be different, with Russell on the train, and me waving to him as the string of cars slowly came to a stop at the platform, and him coming down the steps and me welcoming him with a robust handshake and a grasp of his arm and a smile, such a broad smile, and my heart pounding so that I could hardly catch my breath. If only I could have thrown my arms around him and welcomed him with a manly hug and a kiss! Fantasies spring eternal. Such a greeting between men might have been possible in Paris by now – though only just – but not in Houston. That greeting would have to wait until we got back to my house, now to be our house in my fantasy.

This time, the man I’d come to the train to meet did disembark. This time the broad smiles did greet each other, the hands shake firmly, the hands grasp upper arms. Our eyes met and exchanged the manly hug that our arms could not, here in the station. This time I needn’t have feared that an empty train – empty of the one I’d come to meet – would leave me with an emptier heart. This time, with this man, our eyes embraced even though our arms could not.

My house was close, but the day was hot and his trunk heavy, so we took a taxi. As we rode, I welcomed him with a little pride to his new home. He reminded me that he’d been here before – not to my house, of course, but to Houston, as he took the train years ago from New Orleans to California, on his way to China, where he’d spent some happy years of youth and adventure, gathering news and sketching illustrations for the Washington Post newspaper. When the taxi stopped at my gate, Russell swore that he remembered seeing it from that brief visit in the past, and had dreamt ever since of living in this very house – but I put that down to the irrationality of new love (I know that too well myself) rather than real memory.

Though Russell gave no hint that he noticed, as we walked up the path, past the cast metal dogs, to the porch and door, I regretted that I had not spent more time in the four days since his letter came, clearing up the debris of fallen live oak leaves and branches brought down by the storm. There had seemed so much to prepare inside for his coming, that I’d given no thought to the first impression that the walk through debris might give him of this, his new home – our home together. Surely he wouldn’t let such a small oversight taint his vision of our future together.

Once inside, with the door closed behind us, our arms enfolded each other as they had been longing to do (mine had, anyway) since his foot touched the platform at the station. I didn’t care (and he didn’t know) that my housekeeper was no further away then the kitchen. Arms intent on enfolding cannot be put off forever. One day the world might have the compassion to see that – or those of us with arms longing to enfold might find the courage to show it. For now, at least, we found the courage to show each other, with a long embrace.

At last, when we had had our fill, for this moment at least, of holding each other, he opened his trunk and took out a painting that he had carefully wrapped in flannel shirts (shirts that would not be needed in Houston for months to come), and placed on top of everything else so that he could get it quickly.

“This one is titled A Joy Yet the Banquet Begins,” he said showing it to me. “We’ll put it on the wall in the dining room, so we can see it every day. It will make this my house too, and it will remind us at the start of every day of our joy, and the banquet life has spread for us by bringing us together.”

I took down without a moment of hesitation a faded chromo print that had hung above the mantel for more decades than I’d been alive. My grandmother had put it there. Taking it down was the first change I’d made in this house that anchored me, but also weighted me down. Replacing it with Russell’s painting seemed to lift a weight from my chest. I could breathe in the room as I had never been able to before.

His painting, replacing the relic of my past, made it a new house, our house, in which we could live a life such as those who had passed their lives in these rooms before, could not even have imagined – a life that even I could not have imagined in these rooms till now – but one that now seemed the only life I wanted to live – live for the two of us together.