Left Bank On the Bayou – Gay Russian Style

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This post continues the sequel to my novella The Song of the Amorous Frogs: A Story of Paris in the 1920s. Click the title to catch up on that earlier story. It is now 1937. Our Narrator has returned to Houston, after his youthful Paris years and loves, followed by 10 years, and undoubtedly more loves, in New York City. And so his story continues … You can catch up on Left Bank parts already published by clicking the LEFT BANK tab on my cover page navigation bar.)

“My father – step-father, really – is a cellist.”

How my heart pounded when I heard that word – Cellist – from across the room.

“You’ve probably heard him play, with the symphony or the Josephine Boudreaux Quartet. He’s really quite good. English by birth, but he’s been in America forever. Married my mother after we came to Houston when I was a child. I took his name, though frankly I’ve had some second thoughts, now that I’m older – and now that he’s bugging me about certain things which shall remain nameless. If he keeps it up, one day I may go back to my birth name, Rafalsky – though my mother had shortened that to Ralph by the time we got to Houston. Rafalsky might have been too much for southern flowers, girls or boys, to deal with back then. I know all this is sometimes almost more than I can deal with myself.”

The speaker was the young – not quite so young as Goyen and Hart, but 10 years my junior, so still young in my book – talented painter and theater designer, Gene Charlton. The scene, the house at 3211 Travis Street that he shared with his partner, Carden Bailey, himself a painter of society portraits, especially of the children of privilege, in which genre he had become the Houston go-to choice. Charlton himself painted more interesting things, verging on radical in fact, and with a spark of genius some might think surprising from such an art byway as Houston, way down south on the gulf coast. Perhaps it was that “partnership” that Charlton’s step-father felt the need to bug his step-son about.

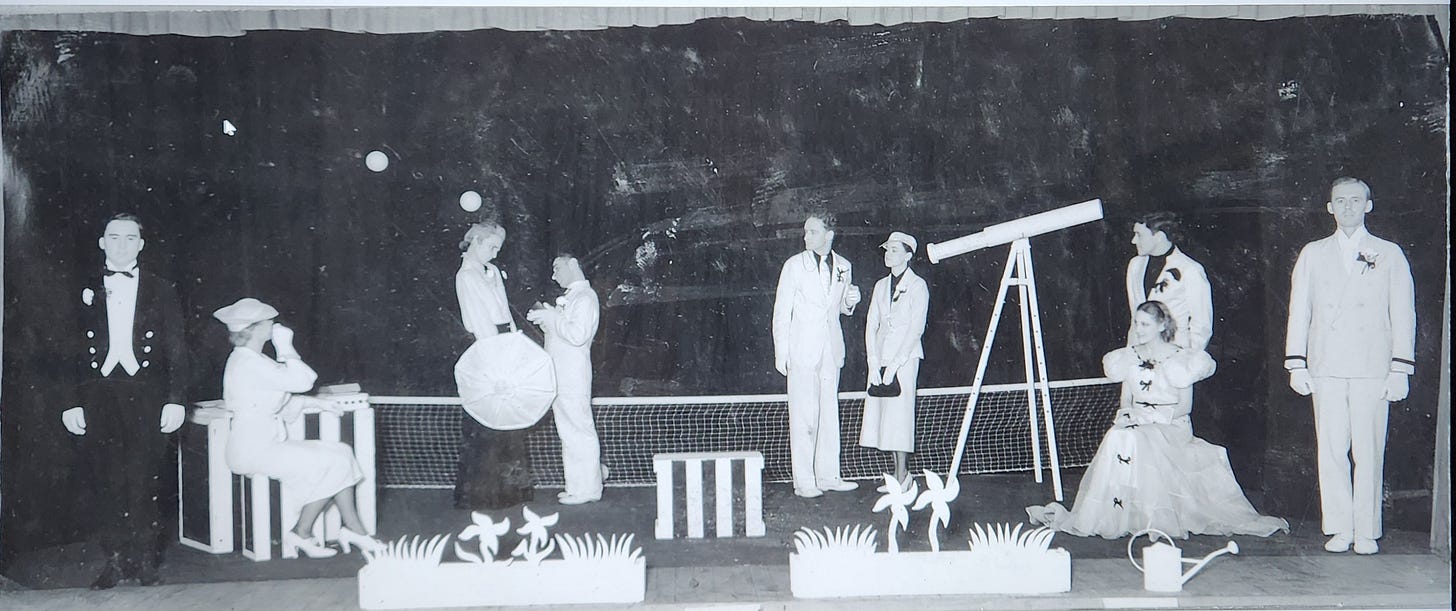

I’d met Gene and Carden through Margo Jones. She’d “convinced” them to design sets for her Community Players theatre productions. First, for The Importance of Being Ernest, they’d created a splendid black and white silhouette setting perfect for the Wilde satire; and now, for the last production of the season, a black and orange room in a Moscow tenement, which set just the right tone for Katayev’s comic play about Soviet housing shortages, Squaring the Circle.

That bit of theatrical flourish no doubt inspired them to recreate their own setting in a “Gay Russian Style,” as their newspaper arts editor friend, Ione, wrote with a wink and a dropped hairpin, “painted a dazzling white … trim turquoise blue banded with deep green scallops … window frames outlined in deep blue and doors in vivid scarlet … yellow dots in the middle of each green scallop.” GAY Russian style indeed! Many of us caught the wink and shared the smile.

And I smiled, looking around the room on this festive May evening, when many of the more talented, and some of the more outré members of the small, but lively, Houston arts community had gathered to pass a couple of recherché hours pretending to be only who we wanted to pretend to be. There weren’t so many places anywhere that we found that possible, but there were some, even here in Houston.

“Baby, you have such burdens to bear!” The irrepressible Margo put the perfect kibosh on even the mock self-pity Gene pretended to, this evening.

“I do, I do,” he said, and he then leapt to other topics. “But Europe will lighten my burden, I’m sure. We’re going there, you know. This fall, with McNeill, for our grand tour. Taking a cargo steamer out of Corpus Christi to save funds, since we’ll be there for months and months. Paris, Florence, Venice – the grandest tour. We’ve been planning it for ages. I’m painting watercolors furiously to make money for the trip – a hundred, so far, at least. And Cardy is dashing out his penetrating portraits of Houston’s young heirs and heiresses. We’ll need buckets of cash to do things in the style to which we aspire. Thank God Cardy speaks French. All I can manage is English – and a little Polish. Rafalsky, remember.”

“Paris” and “Cellist” and “Gay” repartee combined on this May evening in Houston to take me back ten years – more than 10 years now – to that earlier time when I too was young and newly launched into a glittering world of Continental sophistication and “eternal” romance (at least in imagination). What a bittersweet pleasure, seeing other young men like me as I used to be, in youthful naiveté planning their first adventures in the BIG world, at the side of one they loved. Not that I believed deep down that I was so knowing even now, nor so stale. But that first flush of such an adventure was a feeling – an enchanting one – I’d never know again. And I felt a pang of envy at what lay ahead for them, Gene and Carden. Ah, to be young again, in Paris, and in love – with someone, and with art. Even the scent of magnolias wafting through the heavy evening Houston air could not rival such perfume as that.

I almost longed to go on the tour with them. I hadn't been back to Paris since I departed in 1926. For years I'd had no desire to go - and then no reason - and finally no interest. But now, hearing the excitement in Gene's voice as he spoke of the discoveries that lay ahead for them ... Now, the memory of Paris – the allure of Paris – caressed me and drew me close.

I knew the McNeill he spoke of - McNeill Davidson, like me also a former student of Mrs. Cherry, a creditable painter, and now an inspiring teacher to the most gifted and exciting young Houston painters. A woman fighting against the odds in her work, with a family of children, loved, no doubt, but demanding time, attention, energy that could have gone into creative efforts of another sort, the sort on canvas; of a husband, loving and loved, no doubt, but of an older school who tolerated eccentricities like art, only if kept in their place, and not allowed to interfere with a woman’s proper duties as mother and wife; and elder relatives, revered, no doubt, but needing more and more attention as the years transformed them from pillars of family strength (or of family frustration) into dependents themselves.

I, who no longer had such family members to love, be loved by, be dutifully attentive to, could not criticize, only empathize, with McNeill’s almost inevitable disappointment at how much she wished to accomplish in her art and how little time and energy she had to give to it. So it seemed to an observer, at any rate. Mrs. Cherry had hinted as much in her mentions of her former student, co-worker in art and dear friend.

Return to Paris! What a powerful thought, now that I thought it, for the first time in a decade, as a real possibility. Perhaps I would talk to McNeill about joining her little Paris party.

Then almost instantly I remembered a phrase I’d heard from a writer acquaintance I’d encountered in New York: “ You Can’t Go Home Again” – a phrase destined, he’d said, to be the title of his next, and greatest, novel. He’d shown me some of his manuscript, a few pages from a mountain of paper that filled the top of his desk and all the surfaces in its vicinity. He’d seemed so troubled and in such decline that I doubted the novel would ever be finished, but his title lodged in my mind and would not be forgotten – even though I had come home again myself – though only after it had become a home in place only, with none of the family fabric that makes a place HOME in the fuller sense that gives it power for us, whether we’re there in fact or not. Perhaps for me the true phrase should be, “You Can’t Go To Paris Again.” Not the Paris that once was HOME.

Though I’d grown up in Houston, and to Houston had returned, Paris seemed my real home: home to the man I had become, the man I now was, the man I would be, I hoped, for all the life I had still to live. The thought of returning there, even the idea of it, enticed and frightened me as Houston never could.

Well, something to think about, though the likelihood of my making the trip might be slight. I could, at least offer the young men my on-the-spot advice, even if now 10 years out of date: direct them to Café Gaudeamus, the Bal Musette on Montagne Sainte-Genevieve, the Madame’s garden. Perhaps give them a letter of introduction to Pavel, who might remember me; surely, at least, his new lover, Charles Henri, would know my name from our New York days. But would they want, or even listen to, the nostalgic blatherings of one so long past his prime (in their eyes, at least) when they had their own Paris to discover, to explore, for themselves.

I smiled at my conceit and walked out into the spring night. I looked back at the glittering Russian dacha in the Magnolia City, an exotic setting in which all was theater, in which all were playing parts. I heard Margo, now standing in the door, saying, between deep puffs of her cigarette, “Baby, you must come with me to Pasadena. I’ll be there all summer, at The Playhouse. It will be smashing.”

I walked up the empty street, toward the streetcar, which would take me home, an empty house, but a setting in which I could play my own part without threat of contradiction, deliver my soliloquies to myself, alone, without interruption from the eager young just starting on their exciting journeys. I wished them well, but I would not go with them. Not this time; not yet.