Left Bank On the Bayou – Ted's Men

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This post continues the sequel to my novella The Song of the Amorous Frogs: A Story of Paris in the 1920s. Click the title to catch up on that earlier story. It is now 1936. Our Narrator has returned to Houston, after his youthful Paris years and loves, followed by 10 years, and undoubtedly more loves, in New York City. And so his story continues … You can catch up on Left Bank parts already published by clicking the LEFT BANK tab on my cover page navigation bar.)

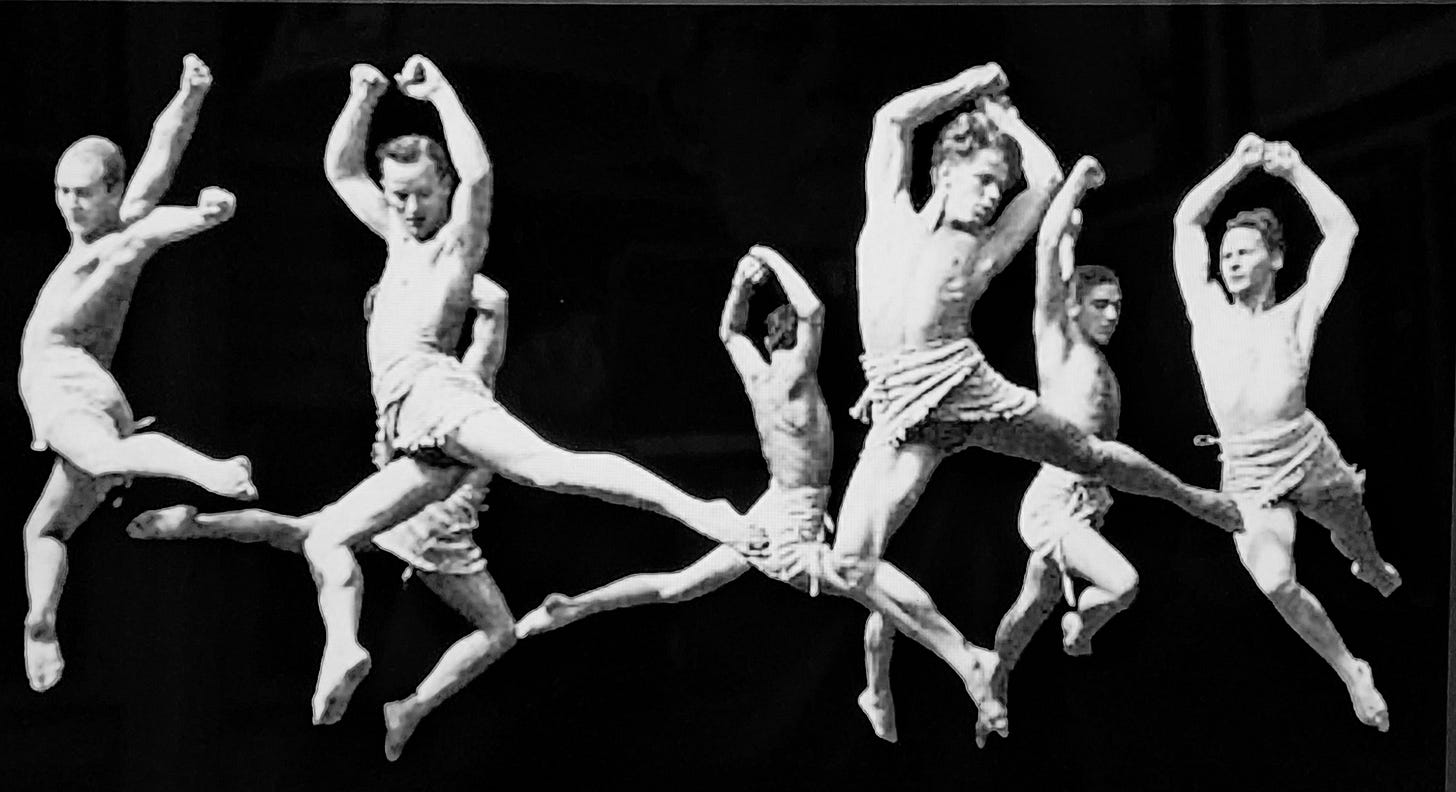

The instant the curtain fell on the final dance of the program, the auditorium thundered with applause. Bravos rang through the air, and most in the audience – disproportionately men, of all ages, in ones and twos and groups – leapt to their feet. It was not so large an audience as the several thousand who had applauded the femininely classic Ballet Russe that I saw in the same space the month before, perhaps, but this night the several hundred on hand (and now on their feet) cheered Ted Shawn and his young men dancers with a masculine abandon that thrilled the heart of even an old jade like me. Not so old, really, but sometimes feeling so.

But not so this night. What I had just seen on stage sent bolts of youth and life through me, and even I, who scoffed at standing ovations except when the very pinnacles of perfection had been reached, found myself on my feet with all the others. I began to think of the praises I would sing in the review of the performance I had agreed to write for the newspaper: “America interpreted in dance … with the program Shawn and his eight personable youths gave Thursday night … the strength of all men dancers … perfection of grace, rhythm, balance and muscular coordination … young, of slight build, buoyantly graceful … the epitome of eager, young America … applause often wild at times …”

Shawn and his beautiful young men returned to the stage time after time, sweat still glistening on their lithe, near naked bodies, holding hands and taking their bows before the adoring crowd. The rush of virile images almost intoxicated.

At last, when the dancers had taken a final bow, the harsh lights of the auditorium came up, telling us beguiled witnesses of their masculine magic that the moment had ended, that the time had come to return to a world not so impossibly perfect as the one we had just lived in for two precious hours, in the company of eight seemingly flawless youths, and their genius master.

As we all walked out of the rows, and up the aisles, and out of the doors of the auditorium, I spotted some familiar faces among the many unfamiliar ones; spoke the occasional “Good evening,” “How are you,” “Splendid” – though I hardly wanted to speak at all for fear casual pleasantries, or even exclamations of wonder, would hasten the flight from that other realm the dance had taken us to, fear that I would be brought back to earth – too soon!

Across the way I saw an august gentleman I had not seen in years. Memories came back, of touches from his hands years ago. Not unwelcome memories of not unwelcome touches. When I was just man enough to shave, but already fully man enough to respond, to welcome the touches even though they surprised at first and frightened a little. Respond willingly, happily, thrillingly.

I had not seen him in decades and might not even have recognized him – time had made such changes in us both – until our eyes met and took us both back to those past times for an instant. Or so they took me back, and I assumed, hoped, they took him back too, to those touches touched so many years before. His eyes, which lingered a long moment looking at me seemed to say so. Then we each went our own ways, he with a young man holding his arm, steadying his slow walk up the aisle.

Once outside, in the crisp February night air, I knew that the precious feelings from the precious respite would fade soon, and I breathed a sigh of resignation – but vowed to myself to keep the images and the feelings alive in memory.

For a few moments I walked behind Billy Goyen and Bill Hart, on the way to their streetcar. The two had watched the dance together, from the highest, cheapest seats. I heard Goyen gushing, as gifted, slightly priggish young novices will: “I received one of the greatest inspirations I have ever felt when I saw the Shawn dancers.” I might smile at his full-of-self histrionics before his adoring friend, but I could not disagree with the truth of what he said. I too had received inspiration which not even my worldly wisdom could muffle, at least for the little while that the lingering euphoria lasted.

At a corner the boys turned and hurried up the dimly lit street to catch the car already slowing at the stop. Young men, actually, not boys, but 15 years my junior, so how could I not think of them as “boys?” I turned the other direction, toward Kelley’s Grill and a late solitary supper, thinking of the evening that was passing so quickly. At least the lights would be bright in Kelley’s, the champagne chilled and the chatter from other late diners lively, and no one but I would notice – or care if they did – that I ate alone in my booth.

After my meal I walked slowly down Main Street, past the movie palaces whose marquees had now gone dark, past the shop windows whose displays of home furnishings and latest fashions held no interest for me, past Levy’s with it’s mirrored kiosk. I glanced, of course, to see if my hair now needed combing. Habits of long-standing will out, no matter the mood or the hour. And a young man standing at the kiosk, comb in hand, glanced back.

Was he the young man from earlier? Perhaps, though I could not be sure, so many young men had danced before me since I passed the kiosk earlier. Unlikely to be the same young man, so many hours later. But maybe; why not? Here I was again myself, not quite the same, for all those young men who had danced, but not so very different, it would seem, when it came time for these late-night glances.

I thought of going closer. Thought of casual comments about the weather and the hour, of lights for cigarettes and directions to places neither intended going. It would be a dance of sorts itself, one danced so many times before. And I thought of the dance (of sorts) that might be danced later, in a room at the Texas Hotel, or my bedroom, childhood bedroom, overlooking the garden of my house. It might not rise to the level of that danced by Shawn’s young men, but it would be my dance – mine and his. Perhaps he’d seen Shawn’s men too, and felt the same inspiration that I felt, and the two Billys, and the five hundred others, at least, who had seen them with us. And even if our dance fell short of the art we’d seen, been inspired by, longed for, it would be ours. Before the dance begins, the possibility of perfection always woos. And I had been won by the temptation many times before, in Houston and New York and Paris – and other places.

And yet this night, even as I longed to know, to feel, something of the paradise that Shawn and his men, through their bodies and their steps, said could be, I was not won over, I did not go closer, I did not begin that “sort of” dance, which might, or might not, be a fitting coda to such an amazing evening.

The chance of “might not” loomed too large to take the chance of spoiling what had been so magnificent. Even though memories of nights with Clem, with my Cellist, with some (few) in New York, and even one or two in Houston, enticed with the possibility – possibility of something splendid – realized …

But there had also been other nights, many, of possibility dulled by the real … And so this night I would not take the chance; I would not tempt fate (as I was being tempted) in the hope that I might thus hold on to that respite from a harsh world – harsh for men like me – that this night had said might – might – be a possibility. I walked on along Main Street and across downtown to my dark house in Quality Hill and a lonely bed, sublime, for this night at least, in loneliness.