Left Bank On the Bayou - Dance

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This post continues the sequel to my novella The Song of the Amorous Frogs: A Story of Paris in the 1920s. Click the title to catch up on that earlier story. It is now 1936. Our Narrator has returned to Houston, after his youthful Paris years and loves, followed by 10 years, and undoubtedly more loves, in New York City. And so his story continues … You can catch up on Left Bank parts already published by clicking the LEFT BANK tab on my cover page navigation bar.)

Some of my New York friends who still wrote gasped in amazement at my return to Houston. Not many did still write, and even those few would likely fade away in time, since the “friendships” had been built mostly on late nights on the town and gallons of bootleg hooch. But the few who still did write wondered what I could possibly find to do there. Or who. As per one, who reveled in his to-the-limit incautiousness – who delighted in claiming that he was a model for Ford and Tyler in their Young and Evil. I could see the mock-regal turn of his head and hear the lisp from his pursed lips as I read his words: “My Dear, how ever do you keep your sanity – or is that sin-ity (I blush!)?”

Often, the wonder came from those who came themselves from small towns in Ohio or Nebraska or other equally far away states from which they had fled, never, they hoped, to return. They clung to the anonymous freedom of New York with the desperation, the terror, of creatures holding on for dear life – even when the price of the life could itself be dear. And so, when one of their tribe – in this case, me – actually did return to his awful place of origin, they felt a new terror, as though the talons of their own awful places might reach out for them. I wondered how many of them would one day go back, as I had, whether by choice or necessity. I hoped that all who did would find ways not to regret it. But likely I would never know, because the letters would likely have stopped by then.

Sometimes the letters came with news of some of whom I would as lief not be reminded. Sometimes they took me back to memories of lost loves and heartaches past – which, even with time and distance, might not have yet fully passed. But a tear in the corner of the eye is sometimes not a completely awful thing, and so I welcomed the letters while they still came, and sometimes even wrote back with news of my new life – and what I was finding to do to make it livable. Perhaps my news would comfort them when their own day to return arrived.

And one of the things I found to make my life livable, even in far-off Houston on the far-off Gulf Coast, was dance. By dance, I do not mean the Lindy Hop, or the Swing, or the Shag, or whatever names such popular revels might be called. Though I might, at times, with enough of the no longer prohibited hooch, attempt those myself. The dance I mean was the Ballet. For, perhaps surprisingly, Houston had long had a history with ballet, which, by the time I returned was becoming even closer. Now, the Ballet Russe made annual tours to our southern city – in the winter, when we were mild and other stops on their list were frigid.

But my ballet mania went further back. Certainly, my taste for it had grown stronger in Paris, with Diaghilev and Ballet Russes at their height, unsettling the world as Nijinsky and others danced to the music of Stravinsky and Satie, costumed by Bakst and Delauney, in settings by Picasso and Cocteau. Diaghilev was now dead, after a life of hard living and exhausting art, and the company that now came to Houston only bore a similar name. But I remembered when Diaghilev had come to Houston in 1916, or at least his Ballet had, with the great Nijinsky himself topping the list of dancers; and, even earlier, when the “incomparable” Anna Pavlova had come in 1911, partnered by Mikail Mordkin, in an astounding first for the city, and for me.

The same Mordkin who came again later, with his own company, and to whom my Houston friend Eugene, wrote his paean in poetry, and published it in the local paper:

My Love, The Dancer,

Is like a horse!

A young horse that prances,

When he dances

Up and down the stage of life.

His smooth and nude and shining body,

His tightly-rounded arms

And legs and hips and thighs,

All are shot with lightnings

From a hundred thousand skies …

Enraged,

My Love, the dancer,

Prances, prances, prances!

Dances, dances, dances;

Up and down the wave-licked shore.

Till his rage can be withheld no more!

Snorting, snarling, roaring,

He plunges into the snarling sea,

Determined to down it

And all its strange myster[y]. …

Strong stuff, scandalizing many, no doubt, when they came across it in their morning Post, but stirring deep yearnings in others, including me when I read it in Houston in 1926, even after the hedonistic Paris I’d recently left behind.

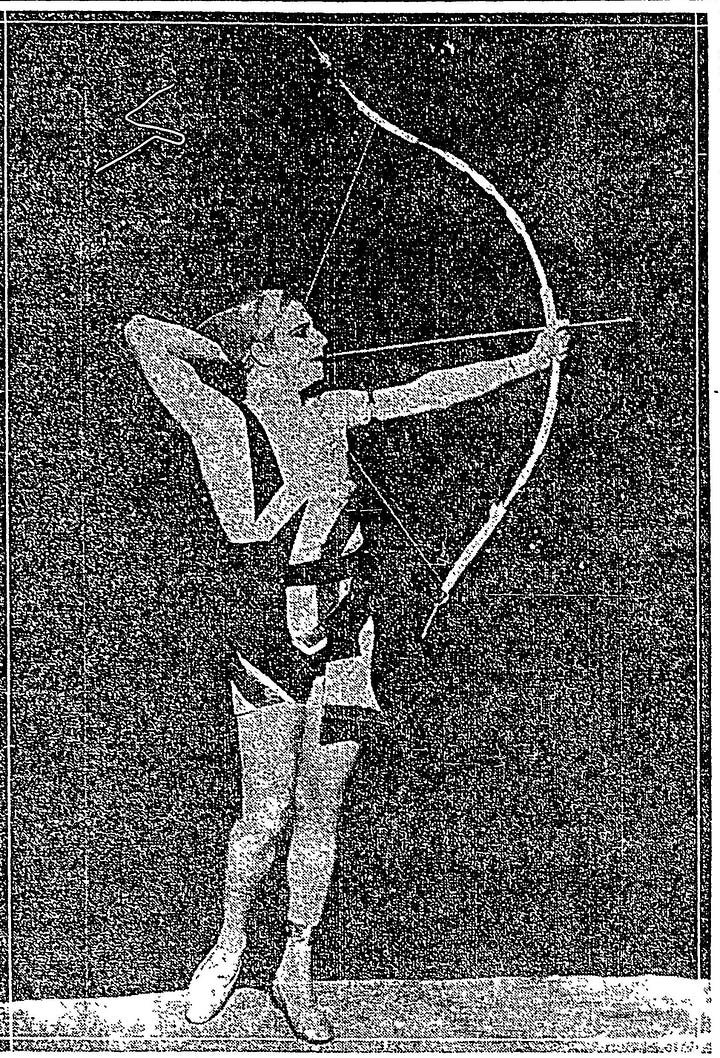

Those earlier encounters had sealed my fate as one addicted to the drug of dance. Now, however, dance even more thrilling than the ballet of Nijinsky, Pavlova and the Mordkin who had so moved Eugene, was coming: Ted Shawn and his all male company. Called by some “modern” dance – though what could be more modern than The Right of Spring had been in it’s day? I’d had a taste of this “modern” dance in New York – and of Shawn, when I’d seen him dance his ethnic dances in programs with his wife in their Denishawn phase. But the very thought of a company composed entirely of men, and men likely minimally costumed with the license the modern-ness of the dance seem to give, revealing “smooth and nude and shining” bodies – male bodies – thrilled in ways that paled even my recollections of Nijinsky in his prime.

I’d bought my ticket the instant I’d heard the news, or as soon, that is, as I could get to the ticket office of Edna Saunders, Houston’s impresario, at Levy Brothers department store on Main. I was not the first in line. I saw many familiar faces eager to get their tickets too – many faces of young Houston men I recognized, even if I didn’t know their names. We all knew it would be an evening we’d long remember – and perhaps, dream about.