Left Bank On the Bayou - Bohemians

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This post continues the sequel to my novella The Song of the Amorous Frogs: A Story of Paris in the 1920s. Click the title to catch up on that earlier story. It is now 1936. Our Narrator has returned to Houston, after his youthful Paris years and loves, followed by 10 years, and undoubtedly more loves, in New York City. And so his story continues … You can catch up on Left Bank parts already published by clicking the LEFT BANK tab on my cover page navigation bar.)

When I’d left Paris in the spring of 1926, to return home to Houston (Mrs. Cherry had not returned until the fall), I’d been a young man with a bruised heart who could hardly grasp that the fairy tales of childhood had not come true, that my Prince Charming – Prince Charmings, as it had happened – had not prized me, once found, above life itself – that, in a stinging twist not part of any of the tales of childhood, they had found their bliss in each other instead of me. Or I imagined they had, with an ocean between us.

By the time I returned to Houston again, in 1936, no longer young, certainly not nearly so naïve, the heart had grown accustomed to bruises, had accepted them as part of life, along with the leaps of joy and hope that preceded them. I did not believe that I had become cynical or bitter – only more knowing from experience in the ways of the lives of hearts in love, especially for men forced to live warily in a world with little sympathy or room when both of the hearts belonged to men. After 10 years, wariness and weariness had blended so thoroughly that I felt sure even a monkish renunciation of love in Houston, if that was what lay ahead for me there, would be preferable – for a while, at least.

And yet I knew that I would not be living a life of solitude in Houston, nor even a life apart from men like me. I knew because I’d made connections with other Houston expatriates in New York, also going “home” – connections that already promised to go with me back to the Gulf.

First among them, the impetuous, exuberant Wilma – daughter of the Houston Heights, poet, girl about town in the Big Apple demi-world, about whom a reporter of Broadway gossip had said in his column, “Wilma, the poetess, is returning to Houston because the first three men she met in N’Yawk offered her their lipsticks between lisping comments on the cut of her gown.”

Indeed she was returning to Houston, but it was circumstances, neither the lisping nor the lipstick, that moved her go back. In fact one of her own poems, “Greenwich Village,” in its concluding lines, advertised the spirit that had drawn her to the bohemian life of “the Village,” which she was bringing back to Houston with her:

And life was lean And beautiful, And love was young and glad – It’s good to be A Village poet And a little mad.

I’d met her in my own about-towning, in the company of Parker Tyler and Charles Henri Ford, two other Southern boys storming the City – Charles had even lived in San Antonio for a time, in his younger days. The two were famous – infamous, some would say – for their portrayal of that very New York demi-world, a queer world, in their co-written novel, The Young and Evil, so scandalous, which is to say, so truthful, that it could not even be published in New York, had to flee to Paris to see print – where Charles followed, and where he – small world – became the “special friend” of Tchelitchew, the Pavel I’d known myself years before (though not, myself, as quite such a “special” friend).

Wilma and Parker had become their own special friends – she even had stars in her eyes for him. Too bad for her, since the stars in his own eyes walked elsewhere, and in trousers – or perhaps I should say to be clearer, less coy, now that Deitrich and other women were already making trousers their own by then – the stars in Parker’s eyes were for men. So it was not that that prompted Wilma to buy her ticket to Houston; perhaps it was something of the weariness I’d come to feel myself.

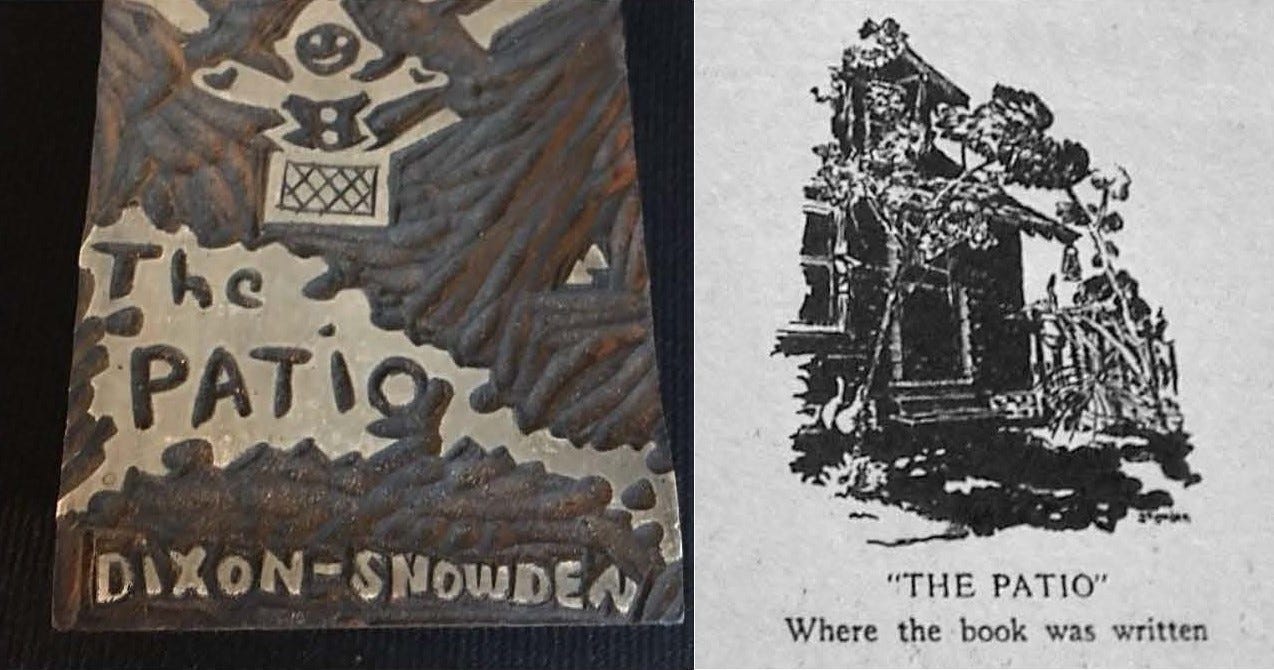

And then there were Royal and Chester, another couple of Texans who’d come to New York to meet, as it happened, and now that they had, were decamping back to the Gulf. Royal, some years older (Chester was my own age almost exactly), was becoming rather famous as a nature writer, story teller and lecturer. They had met when a publisher hired Chester, a young artist, to draw the illustrations to one of Royal’s books. They formed a partnership that went beyond books and publishing, and had already returned to Houston, to the “Patio,” their shared residence/studio on Truxillo Street, Chester painting in the main house, Royal writing in his study out back. They hosted gatherings – their “vespers,” as they called them – of Houston literati, which might have been called salons in more sophisticated settings – settings with running water and electricity. But the rustic life, meaning the life of the mind and eye, and a life together, seemed enough for them.

I knew them well enough in New York to stay in touch – though to tell the truth, they held some ideas, metaphysical almost, which I smiled at, and found difficult to take seriously. But they were both lovely men, and so when I returned to Houston I knocked on their door almost before I’d unpacked my trunk, and I became a regular at their amusing soirées.

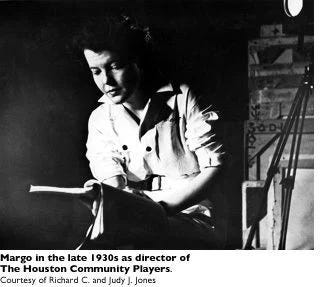

One of the most amusing people I met there was Margo – Margaret at birth, but “Margo” as she’d christened herself, and she withered with a glance and a tart word any who dared to use that other name. Though “amusing” is such a pale descriptor for such a force as she. In the summer, she’d stage-managed the Houston Federal Theatre production of Chester’s play, Pioneer Texas. How quaint: he was a better artist than he was a playwright by far – but bills had to be paid. Margo’s theatre dreams went far beyond stage managing. One day she would have a theatre of her own, she proclaimed, and one day she would direct on Broadway. Even as one who knew the New York theatre, and whose Broadway dreams had paled in their own way over the years, I could almost believe hers would come true. Even now she, and her friend, aspiring playwright Zoe, were away at the Moscow Art Theatre Festival, in the company of New York critic Brooks Atkinson, playwright Lilian Hellman, and Al Hirschfeld, theatre world caricaturist – though how welcoming those Broadway luminaries might have been to a pair of brash young women (still girls, almost) from Texas – almost as far from New York as Moscow, and more exotic – who could know.

Through Margo a queer Houston world had begun to open for me, a world of theatre and art and writing, and of queer vibrancy, that I could hardly have imagined possible along the banks of sluggish Buffalo Bayou. Young actors and artists and writers and hangers-on, who could not resist – had no desire to resist – when Margo called them to join her quest to “integrate all the arts,” which meant, when she said it, direct all the arts toward fulfilling her own theatre dreams. Because for Margo, life was theatre and theatre was life, absorbing everything and everyone.

I could only be grateful that this tribe of youngsters, most 10 years my juniors at least, seemed inclined to include me as one of their number. How lucky that, as Mrs. Cherry noted, I at least appeared to be younger than my age. They might not have been so welcoming of a man as old as I who showed in his face the years (and wisdom) he’d acquired. Because wisdom, and a wrinkled face, often do not rank high among the young.

Margo had even talked with me about writing a play for her, that she could use to found her theatre company when she returned from Moscow. And I had begun to outline one I thought (hoped) might appeal to her. How disconcerting, I sometimes thought, for one as mature as I to be wondering if I’d meet the expectations of a young woman of no real record in the field in which I’d toiled for a decade already. I almost regretted saying I’d do it, but even if you resisted at first, eventually you gave in, because “you couldn’t do anything else,” as Cardy, one of the young artist set said, as we commiserated over a drink one evening after Margo had had her way with both of us. She larded her cajoling with “darlins” and “babies” and “sweeties”, but you knew you wasted your time demurring, because she had a way of making sure that she achieved her objectives eventually. And so you went along, and in the end were glad you did.