Left Bank on the Bayou – Tea and Memory, with Mrs. Cherry

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This post continues the sequel to my novella The Song of the Amorous Frogs: A Story of Paris in the 1920s. Click the title to catch up on that earlier story. It is now 1936. Our Narrator has returned to Houston, after his youthful Paris years and loves, followed by 10 years, and undoubtedly more loves, in New York City. And so his story continues … You can catch up on Left Bank parts already published by clicking the LEFT BANK tab on my cover page navigation bar.)

It could be that the best part of Paris is the memory. Because in memory there’s no need to acknowledge the grit of reality, but only the romantic glow of the Paris “we'll always have,” as we'd like to believe it really was.

The thought was not completely new to me, but it came to mind again on a fall afternoon in 1936 as I sat in the antique parlor of a Houston house I had visited a hundred times before, over the decades of my life.

“Do you remember our evening in Paris in 1925?” asked Mrs. Cherry. “When we ate tête de veau, and then went to see Modigliani’s paintings – you for the first time, as I recall – and after that, thrilled to Josephine Baker’s Danse Sauvage premier at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées? What a splendid evening! With Clemmie Tan and your Cellist – and, later, that fellow from Chicago, Clem. How long ago it seems now.”

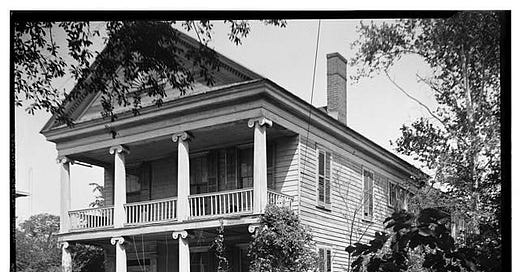

Mrs. Cherry flooded us with these fond memories as we sat in her parlor in “The Cherry House.” That is what everyone called the lovely, white-pillared, Greek Revival residence that Emma Richardson Cherry and her husband, Dillin Brook Cherry, had lived in for decades – much longer than previous owners, William Marsh Rice, namesake of The Rice Institute, or the long-forgotten Nichols who had actually built the house in 1850. We sipped our tea from delicate porcelain cups in the parlor after a pleasant hour in her studio, the place where she painted, of course, but also where she taught the many young Houston artists she had been helping find themselves as artists for as long as she had lived in the house. I had been one of those students myself, years – no, decades – before.

Though not quite so “historic” a structure as the Cherry House, my own house still counted as antique by Houston standards. As I looked around Mrs. Cherry’s room, I thought of my own “parlor” – what an antiquated term in 1936, but how apt for that front room of my family house, not much changed since the high Victorian stuffiness of the 1880s had filled it with uncomfortable, carved and inlaid wood and horsehair chairs and settees around rosewood and marble tables – incoherent blendings of Herter and Belter translated into new dialects as those styles made their way from the showrooms of New York, down the coast and around into the Gulf, to the workshops of New Orleans – and then to the front rooms of Galveston and Houston – showy rooms of questionable taste decorated by grandmothers, like my own now long departed MawMaw, who found themselves, circa 1880, with the means for lavish display – lavish by the provincial standards of Texas at the time – but without the “sensitive” sons to help them modulate it. I smiled, thinking how MawMaw could have benefited from my help – or even more, from that of some of my Paris and New York acquaintances. Still, I had not yet been able to bring myself to change anything about the house; perhaps I never would.

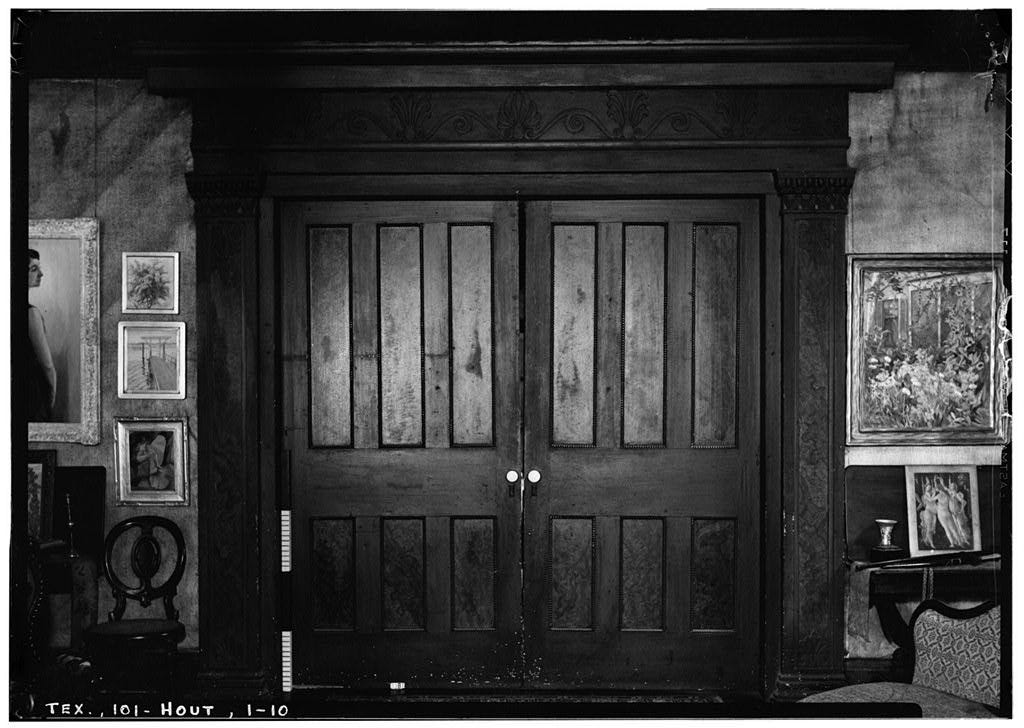

Mrs. Cherry needed no such “sensitive” helpers to make her own room magnificent. Around us, on her walls, hung some of the Cubist studies she had done all those years ago, in Lhote’s atelier, in Paris. Also, other pieces she had done in the 1880s – copies of masterpieces in the Louvre, and her own early Impressionist canvases and watercolors, done at Giverny in 1888 and 1889 – where she had gone to visit Mary Hoyt Seller, her girlhood friend and traveling companion on that first trip to Paris – her companion until Mary met and fell in love with the charming Englishman, Dawson Dawson-Watson.

When Mary and Dawson married, after a courtship of barely the winter months, he took his new bride to Giverny, where he lived in the fledgling art colony developing there – and where Cherry visited the newlyweds, and painted alongside Dawson, at the start of what had become a nearly 50 year artistic friendship. It was partially that friendship which had brought Dawson to Texas years later, to San Antonio, so that he too was now a “Texas” painter. The Dawson-Watsons had even lived some months with the Cherry family in this very house, small as it was for so many personalities and talents.

But her Cubist and Impressionist paintings were not the only pieces on the walls. Fabrics and objets d’art brought back from her studies and her travels filled every inch, things purposefully selected to adorn the “artist’s home” she envisioned for the venerable, historic old house that she loved so much – and which she had made the artistic center of Houston – the center, that is, as far as real creation was concerned, and not just the superficial, showy palaces that all the new oil and old lumber money of Houston made possible for the rich, both nouveau and ancient, of the booming city.

I always found it a nourishing room to sit in – even though stuffed full, and not what anyone would call “modern,” despite its owner/decorator’s desires to be modern, at least in art and mind, herself.

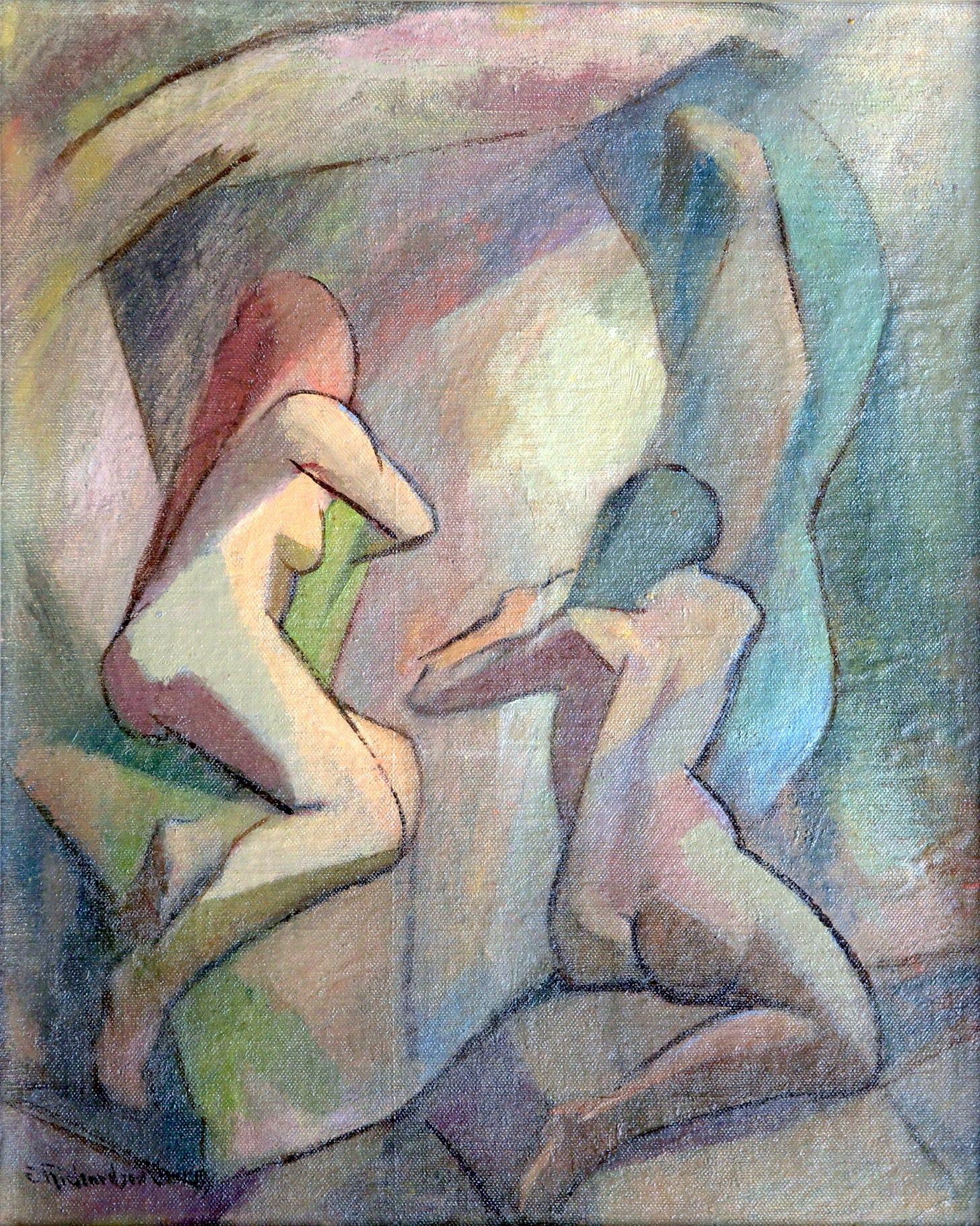

In her studio, she had shown me her latest paintings – wonderful canvases, in which she joined her mastery of color, with impeccable drawing and a long-honed talent for revealing the essence of the people, places, objects she painted, not just their surfaces. In what was already becoming a slightly old-fashioned manner, she always painted “something,” not just the abstract shapes that were becoming fashionable. She’d had her early training in the 1870s and 1880s, from William Merritt Chase and Luc-Olivier Merson, among others, in New York and Paris, at a time when paintings had to depict something. But always wanting to be “Modern,” especially in her art, she had studied modern color theory with Hugh Breckenridge and Henry McCarter, in Pennsylvania; and she had gone to Paris in 1925 to learn Cubism from André Lhote. I had briefly studied with him too.

And she had learned Lhote’s lessons well. She still incorporated Cubist elements into her works when she could, sometimes masking the cubist under-structure with “sheer prettiness,” as she said. Ever the professional, she painted to sell – and, after so many decades, she knew what would sell in Houston. Some criticized her for bowing to her market, for deception. So be it. An artist must eat and have a roof overhead in order to paint – even one who lived her creative life, metaphorically and sometimes actually, en plein air. Mrs. Cherry was no “Sunday painter.” And so she did what her profession demanded, and she did it beautifully.

“You’re right, I think, in coming back to Houston now – now that you can be here in your own way,” she said.

Though we had never talked in detail about “secret” things, being a woman of the world, she knew – as she had let me know all those years ago in Paris.

“I spent years in New York as a young woman, and, if it had been only my own wishes to consider, I’d have spent more time in Paris, perhaps stayed there. I even, for a while, thought of moving to California when my brother, Edward Richardson, went there. But I don’t regret my decision to remain in Houston. No place is perfect, no matter how we see it in our memories or our dreams. I believe in my heart that life is what we make it, taking the good and the hard together, no matter where we are.”

We sat silent for a few moments, both thinking, no doubt, of Paris – perhaps the Paris of our memories and our dreams.

“Maybe Paris seems long ago because it was,” I said. “Ten years! I was so young!”

She laughed the beguiling laugh her friends loved. “I can’t say the same for myself,” she said, “Then or now. But you are still young. What? Thirty-five? And look 10 years younger. So much is still ahead for one so young.”

“What can pass for young, sometimes, in a dim light,” I said, pleased that she gave the compliment, but aware that it was a compliment as much as a reality. Especially aware since I had now fallen in with a younger set – some of them actually 10 years younger – in the art and theater circle that had flourished in Houston since I went away, 15 years ago now, first to Paris, then to New York. How much the city had changed over those years. How much I had changed. Time would tell if the two of us had changed in ways that would make a Houston life the life I wanted now.

Always enjoy the photos and paintings that illuminate your writings .

Bautiful memory.

Shirley