Left Bank On the Bayou – Lorin

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This post continues the sequel to my novella The Song of the Amorous Frogs: A Story of Paris in the 1920s. Click the title to catch up on that earlier story. It is now 1938. Our Narrator has returned to Houston, after his youthful Paris years and loves, followed by 10 years, and undoubtedly more loves, in New York City. And so his story continues … You can catch up on Left Bank parts already published by clicking the LEFT BANK tab on my cover page navigation bar.)

“Come in, My Dear! And join the revelry!!”

Wilma handed me a glass of cheap “likker” as I came through the door of her apartment. I took it from her, smiled and took a sip, and then we kissed, cheek-to-cheek in the French style, but accompanied by the loud “muah” of American camp mockery of such fey Frenchified frippery.

“You already know many of the boys,” she said, as she gestured with a sweep of her hand toward the roomful of handsome young men, like a self-satisfied madam: Cardy Bailey, Bill Hart, Albert Horrocks, Drew Robert-Shaw – and one I didn’t recognize.

“Do you know Lorin?” she asked, presenting him like a bud among the blossoms in full flower.

Lorin!

His green eyes captivated me, and a tsunami of red curls crashing over his forehead swept me away.

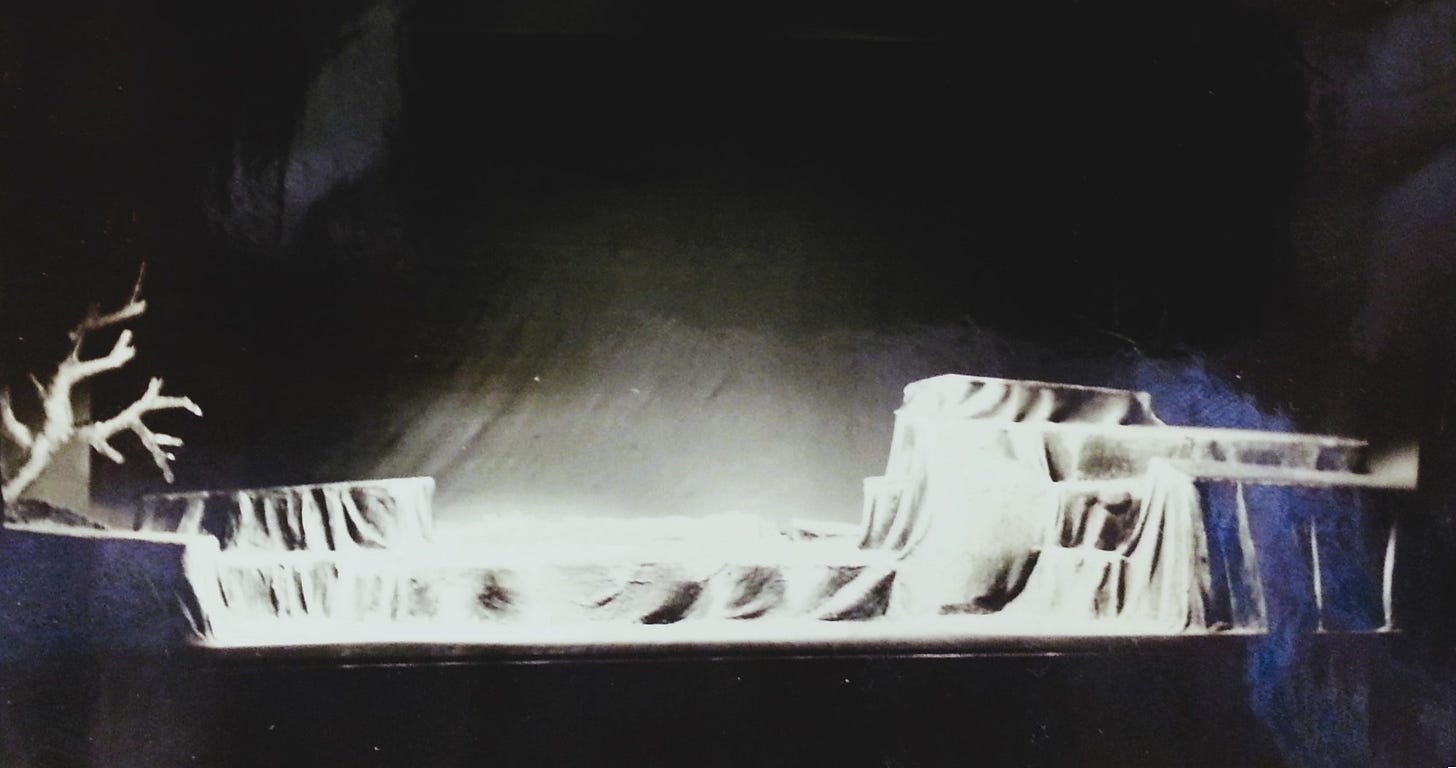

Lorin! Such a “sweet” boy, as they sometimes said, when it would really be “pansy” or “fairy” if just among themselves. Sometime in the fall he’d joined Margo’s theatre company; he designed sets for her productions, play after play, always creating exactly the right tone within which the actors could be alive, if not real, as they'd have to be to live in the real world the other side of the theatre doors. He also carved masks in wood - quite nice ones - taking Balinese originals as his models, but then making the style his own. It wasn't hard to see that he was creating worlds and wearing masks he needed to exist so he could live in them himself, never mind that world beyond the theatre doors.

I think it must have been that I saw in him elements of myself at his age (almost 20 years younger!) that first drew me to him, the struggles he seemed to be grappling with – bravely or desperately, or maybe both at once. Hard to know, or feel confident in, what he might have seen in me, a man so much older, that drew him to me – harder still to believe it might be genuine feeling and not simply grasping for a hold, any hold, as the treacherous ground crumbled away beneath him.

I don’t remember if he reached out a hand first, or if I did. I suppose I should take responsibility, as the mature one – the one old and experienced enough to know about such things – to know better.

Whichever reached out first, the proffered hand found a welcoming other.

As we worked together evenings and weekends at the Community Players theatre, in a repurposed city-owned building on the banks of Buffalo Bayou, he hung on my stories of the bohemian life in Paris and New York. Young as he was, he had traveled nowhere, though his dreams had already taken him around the world. The glaze of fascination came into his eyes as I told tales (tame ones, but fascinating none the less) of Paris: of Tchelitchew and Cocteau, names he did not know already; of Josephine Baker and Gertrude Stein, names he did know, from the magazines and the news. Stein had even made a stop in Houston during her American tour of 1934/35.

When I mentioned knowing both Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler in New York, his eyes widened. Their names he certainly did know. Wilma had taken him on as one of her Houston protégés (and projects), and had told him many stories about them – particularly her darling Parker. Which made my added stories, from a somewhat different angle, the more thrilling to him in his budding curiosity, even though I only hinted at some aspects in that early stage of our acquaintance, out of deference and caution with one so young.

I knew some of the questions he yearned to ask, though as yet he had neither the words nor the courage to ask them. I vowed that in my role as mentor to him, I would answer the questions truthfully and fully when he did ask them. I knew sometime he would. I knew it from remembering myself as a young man like him. How like a father with a son – and how unlike that relationship either of us had known with our own fathers. I had not yet begun to think I might also fill other roles in scenes we both might soon imagine. In a phrase that seemed to be becoming a favorite for me, those scenes were for now still “for the future.”

And then one crisp January evening, not long after our New Year’s Eve meeting, as we finished our work for Margo’s latest production-in-process, the future, as it linked the two of us, arrived.

He’d been telling me, with abundant youthful excitement in his voice, about his new job as apprentice window dresser at one of the city’s lesser department stores. I’d been regaling him (or was it attempting to impress him) with recollections of the splendid windows I’d seen all those years ago at Samaritaine and Le Bon Marché in Paris. As usual, he seemed captivated by my stories, looking at me with sweet puppy eyes, as he let my words transport him to places he ached to go.

How could even my worldly wisdom resist those eyes. It was as though I’d been looking into them my whole life and seeing the connection I’d always longed for. Never mind that he might be young enough to be my son. He was not my son, and he was old enough, so all the legal measures said, to know his own mind and make his own decisions. Except, of course, that neither of us had the legal right – some might also have said, the moral right, though I’d learned through painful decades to dismiss them as wrong – to make the decision (not a decision of the mind so much as one of the body) we were both in process of making then.

But why be coy? No one will ever read this – certainly none of the moral wrongers. It became clear that this was to be the night we would spend together, not as father-figure and substitute son, but as man and man, no matter the differences in our experiences, our backgrounds, our ages. The law of the land might label us outlaws – even segregate us as particularly evil in the prisons they might send us to if they found us out – but the law of nature, the nature we were as much part of as any others – gave us license to join with each other in the way we both wanted to join.

Since it had started to rain a bit, and since I had my car, and since he lived not far from my own house in Quality Hill – though in a neighborhood not quite so faux-grand, perhaps, a neighborhood where he lived with his mother and his many siblings, now that his father had started another family in Beaumont (started, actually, even before he acknowledged them and moved to join them) – I offered him a lift.

The rain made the offer and the acceptance easy. Not even the moral vigilantes could raise eyebrows – though in truth there were none of that ilk in Margo’s circle, so we had nothing to fear in that regard from our Community Players fellows. If anything, from them we might be in for a little gentle ribbing, all in good, encouraging fun, and a few slightly off-color innuendos (very slightly off-color – it was a mixed group, normal as well as queer, even for its thoroughly tolerant, if unspoken, views of such things).

The drive, from the makeshift theatre on the banks of Buffalo Bayou, to the part of town in which we both lived, took only fifteen minutes. The rain had turned to drizzle, but still I drove slowly. For years in Paris and New York I had not driven at all, and, though I’d had the use of my inherited car in Houston for months already, I still walked almost everywhere, so driving seemed exotic, my skills at it rudimentary, especially on wet streets.

But neither of us wanted especially to hurry. We still had a few lingering reluctances to shed – me that Russell still filled the first place in my heart and my plans; Lorin that this was not another of the school-chum dalliances he’d stumbled his way through so far. But, as I fixed my gaze on the slick street, he reached out his hand and put it on my knee – and reluctance of whatever nature, for both of us, faded. I glanced a quick glance at him. We both smiled. I looked back at the street, still nervous about the rain, though now not just the rain. But as he left his hand on my knee, nervousness joined reluctance in flying away.

I didn’t ask, and he raised no question, when I turned down the street that would take us to my house, instead of the one that would have taken us to his. I would not be delivering him there. How his mother would know not to expect him, and not to worry, didn’t even occur to me to wonder. Perhaps he’d already let her know somehow (and sometime) that she needn’t worry. And, in fact, she needn’t. He would be in good hands. And so, I hoped, would I. Though I should have remembered, because I knew it all too well already, from experience, that putting one’s heart in youthful hands could sometimes be anything but safe.