Left Bank on the Bayou – Home to Houston

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This post begins the sequel to my novella The Song of the Amorous Frogs: A Story of Paris in the 1920s. Click the title to catch up on that earlier story. I’ll be publishing new parts of this current serial every Wednesday till finished. You can view all the parts, once published, by clicking the LEFT BANK tab on my cover page navigation bar. It is now 1936. Our Narrator has returned to Houston, after his youthful Paris years and loves, followed by 10 years, and undoubtedly more loves, in New York City. And so his story continues …)

I had come back to Houston from Paris in the spring of 1926 thinking I might stay. But after the banquet of Paris, Houston, then, seemed like a famine. Especially for a man like me, who had discovered in Paris, not just that I loved other men – I already knew that, even long before I could say it to myself or anyone – but also that in a few places, Paris chief among them, it was possible to live life almost openly as a man-loving man, to go through the days and streets with love beside me, no need for hiding or shame. Almost none, anyway – old habits die hard, even in Paris. There had been heartache for sure – first Clem, then, my Cellist, then the two of them together! Though by now I had lived enough and matured enough that I had no hard feelings toward them; I only hoped that they’d found happiness in each other.

But after the paradise of queer Paris (somewhat flawed, perhaps, but still paradise), Houston, in 1926, had seemed intolerable. I quickly sensed that there could be no life for me in the city other than that of my Mother’s son – whether dutiful or rogue, it hardly seemed to matter: either way, my Mother’s son. Oh, certainly I could have skulked off to New Orleans from time to time, and perhaps found a night or two of respite in some French Quarter bar or back alley. But in Houston, only a proper me, a good-boy me, would do; and I knew that after Paris, where I had lived my truth and found I liked it, even though at times it broke my heart, I could not – would not – go back.

And so, after a few months, I’d gone to New York – only slightly better than Houston, certainly no match for Paris, but with the advantage, at least, of being huge, with ever changing multitudes – “City of Orgies,” as Whitman had called it, and still the city of “the swift flash of eyes offering me love” that it had already been in his day. In New York no one had known me from birth, known my people for generations, thought it their right to know everything I did, everywhere I went, and with whom. And, most of all, for me in New York, my mother, whom I loved, but for whom I would never grow out of childhood, was a thousand and more miles away. In New York I could live a life that was more than a constant stream of childish fibs. Though the fibs did still get told during the rare visits home.

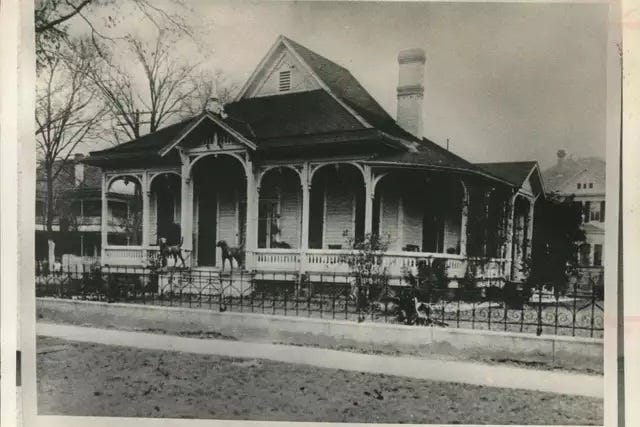

But now mother was dead. My father had preceded her years before, and my sister too, my only sibling, one of the multitude taken by the Spanish Flu back in the teens. She had died before giving my parents the grandchildren they longed for – grandchildren I would never give them, certainly – so I now had no close family in Houston. The family home, built by our grandfather in the 1860s in what came to be called “Quality Hill” – called that by those who built their houses there, at least – came to me, as the only remaining heir, the end of the line, to state it bluntly. Since I’d grown weary of my New York life anyway, I decided to move back to Houston, to live in the house I’d been born in, grown up in, thought I’d never live in again.

I’d even made my childhood room my room again, in part because I liked the view over the garden from the window. I smiled, thinking how such thoughts mirrored the joy I’d felt looking out my window in Paris 10 years ago, over the Madame’s garden – joy magnified as Clem, and then my Cellist, stood beside me also looking, or lingered in bed, calling me back. But, even more, I chose the room again to prove to myself that I’d grown up, that I’d matured enough to not let it keep me the fearful child I’d been when living in it those years before – fearful, most of all, as I became aware of myself and the world, that my parents, my family, my town would see the kind of boy, then man, I was becoming: one whose love “dare not speak its name.”

Houston had grown so much since I’d gone away that the house – my house, as it had become – now sat among businesses rather than the other genteel residences that had been its neighbors in my childhood, or the open fields all around when grandfather had built it. It had become a faded beauty set in the fading remnant of what had tried to be a sort of Paradise garden for a reborn new south, a vision bustling Houston had proved too impatient to let mellow into a local version of the antique New Orleans Garden District. Before too many years I would probably be forced to sell and move elsewhere, perhaps even move the house itself elsewhere, just as Mrs. Cherry’s house had been moved one night in the 90s, from its original site on Market Square, out to distant Fargo Street, then almost in the country it was so far away. The taxes on such a lot so near the commercial center of this now burgeoning city would become too much for my modest income, even adding my inheritance from parents to the legacy left me by my sister.

I would always be grateful to my sister for her forethought in leaving me that legacy at a pivotal time, making possible my life in Paris, a life which had changed my world forever, a life which I’d come to know was indeed the “movable feast” Ernest had dubbed it. I sometimes wondered if she had perhaps known better than I what I would need to become myself, and that she could give me the means for the task, as James had for his “Lady” in his famous novel. I wept that it took her death to make my own life possible – my real life as the man I was, not the man all my history had said I “should” be. Perhaps she knew me better than I could have imagined, and watched over me from wherever she had gone. I saw my life, in part, as a tribute to her too short one, and pledged to myself to be the best, the truest man I could to honor her.

Even her legacy, and the little left by mother, however, would not keep me in the house forever. Certainly the little I earned by my writing would not do so either. It pleased me that I sometimes had poems printed, and that my latest play (after the dozens that came before it), had made its way to a stage or two. But hardly any money came from either poems or plays. And the articles I sometimes managed to sell to newspapers turned into little cash.

But that was a concern for the future. Just as the passing of mother, and all my family, made my reasons for fleeing to Paris, and then New York, a concern of the past. Now my challenge for the present was to build a life in Houston, that I could embrace as my life, and live proudly.