Left Bank on the Bayou - Keep the Music Playing

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

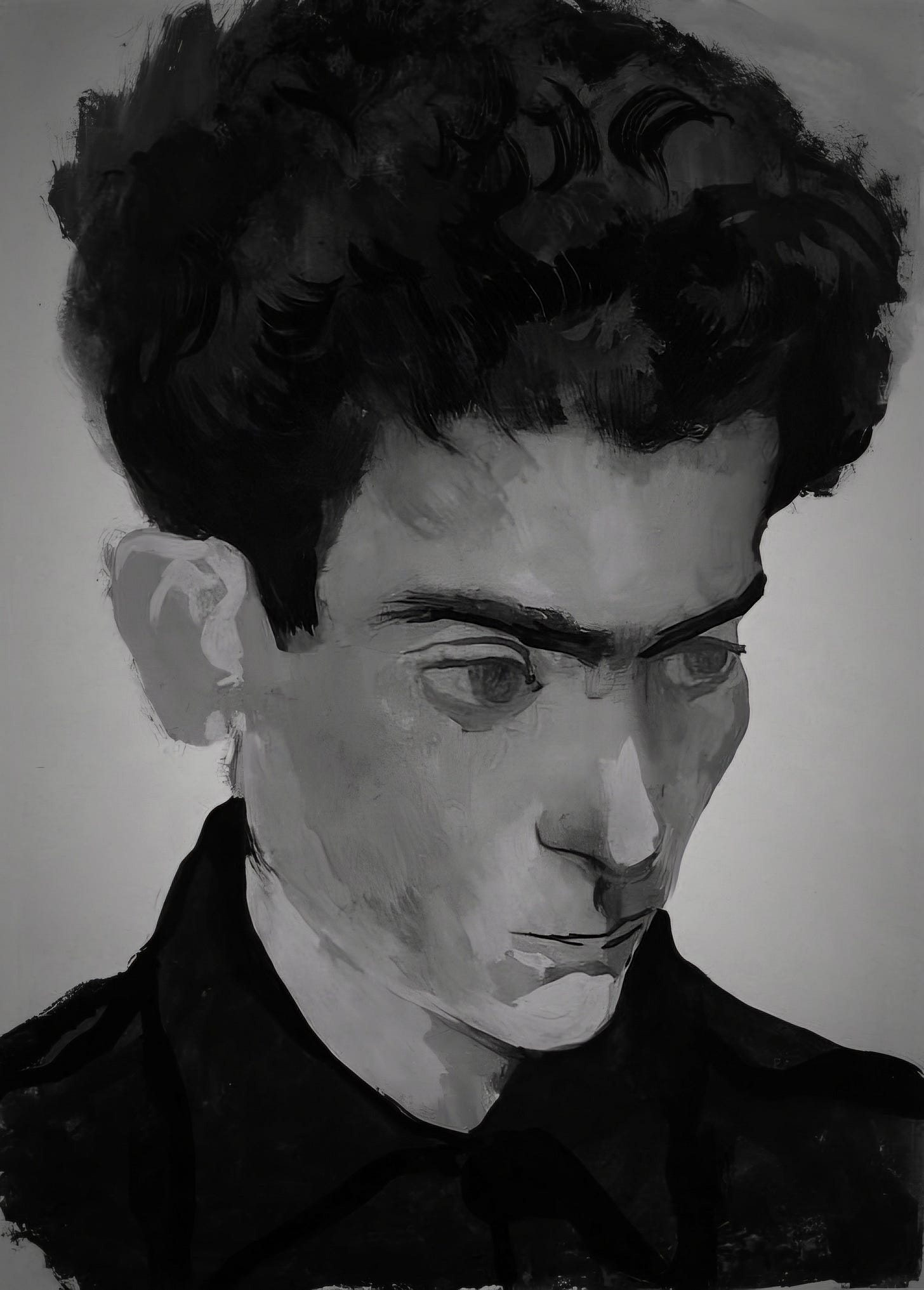

… and in a twist unlikely enough to try the credulity of even the most devoted readers of romance novellas – and flaunt the audacity of their authors – not only My Cellist on the landing, but Clem as well – standing off to the side, watching him play, listening to his music, beaming a bit, as I had beamed that evening all those years ago in Paris, hearing the same music curling up from the floor of the antique Arènes de Lutèce, drawing me in – drawing my heart in – until there could be no escaping – even had I wanted to escape.

“Suspend disbelief,” Coleridge said. Suspend probability as well.

But probable or not, there they both were, before me now on the upper landing, a massive painting by El Greco rising up behind them through the arches, The Assumption of the Virgin, rising as high as the music.

Flooded with feelings so overwhelming I stood no chance of knowing what they were, I became one of the small audience circled around My Cellist, across from Clem, listening and watching, first one of them and then the other. They did not see me; or, if they saw, did not recognize me. Not that the passing years had changed me so much, just as they had not so changed them. All older, of course, beginning to grey, waists beginning to thicken, faces beginning to wrinkle, but still the same men we had been, eyes still sharp enough to see beyond the changes. I recognized them instantly, the music priming my ears, and eyes for those I knew I’d soon see (for one of them, at least) as I rushed up the steps. But their eyes had no reason to suspect they’d be looking at, seeing, me.

I had the advantage of them: I could watch, know those I saw, grapple with what I might say to them if it came to that, decide if it might be better (better for me, no thinking yet of “better” for them) to simply fade away and leave the past the past.

But the past isn’t past. Someone had said that, or would someday. So there was no hope of fleeing from it. Just as there had been no hope of escaping the siren tendrils of that music I’d heard then, and now heard again.

I thought I had seen them for the last time that evening in Paris when I’d glimpsed them through the window of Café Gaudeamus, sitting at the table I’d sat at so many times on so many perfect evenings with each of them separately, before I no longer had a place at what had become their table.

And later, when I left Paris to return to the States, I thought I left them behind. But I soon found that I was wrong. That past, with them part of it, stayed a perpetual present for me, everywhere I went, with whomever, later on. Not in a painful way, later on, but persistently.

Still, I never anticipated encountering them again as more than memories. Yet here they were. Here I was. Not even the most skeptical could fail to see more than coincidence in it.

My Cellist brought the music to an ethereal end (exquisite seemed too impractical a term), and nodded in appreciation of the applause. Clem applauded with the others, as did I; and I watched as their eyes met, and My Cellist smiled at him. Watching, I saw them look at each other in a way that made me envious. Had either ever looked at me in that way? Had anyone? I wanted to think so.

After a few moments, Clem looked across the landing, and his eyes, in their scan, came to rest on me. Slowly (so it seemed, though only moments more) the look of remembering, and then of recognition, and then of disbelief filled his face. His applauding stopped, hands still raised, and his eyes widened. My Cellist, seeing the change in Clem’s face, looked my way too.

I knew it was too late to flee, but, oh, how I then wanted to. I could not imagine what any of us would say when the now inevitable need for saying something came. For a few seconds I thought we might all just agree to pretend not to recognize. I half wished that might be so. Almost half wished it, but not quite.

Then My Cellist stood up, and Clem came boldly across the landing. He put out his hand to me: “I can’t believe my eyes!”

My Cellist, still carrying his cello, came up beside him: “So it is truly you?”

“Yes, truly,” I said, shaking Clem’s hand, and smiling at both of them.

“And do you live now in Chicago, as do we?”

I explained the reason for my being in Chicago, and introduced them to McNeill, who had joined us.

“Lovely,” My Cellist said. “But not the Houston lady we met with you at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, I think. We have been amis à paris many lifetimes ago,” he explained to McNeill.

Clem told us that he had returned to Chicago at the death of his father. The family business needed Clem to head it, as did the family. My Cellist had come with him, as a matter of course, an arrangement that all in Clem’s family, and his social circle, agreed to understand as a matter of patronage rather than partnering, which they could not have admitted to understanding.

My Cellist (I would always think of him as My Cellist, never mind that I’d known for years and years that he’d become Clem’s Cellist – or someone else’s) taught private students, and played in chamber ensembles with a specialty in modern French music, and hoped, one day, to secure a chair in the Chicago Symphony. His playing warranted such a chair, Clem declared, but such chairs were rare.

McNeill, mistress of getting to the heart of things, with her curiosity and her questions, took charge of the conversation then, and lifted the weight of the disorienting (because so completely unanticipated) encounter from the shoulders of the other three of us. I stood back half a step, deferring to her completely, listening as she wondered to Clem if Mrs. Cherry – that other Houston lady – hadn’t described the meeting at that Paris theatre those years ago: Was it at a show performed by that American dancer, Josephine Baker? Clem confirmed that it had been. Had they been back in Chicago long? A few years now. And did they both like it? I more than he, but I have my work at the business – but how we both missed Paris. I was there just two falls ago, for the Exposition Internationale. We had left already by then. Oui, Paris est magnifique, but Chicago n’est pas mal either.

With no necessity to take an active part in conversation, I stood back half a step and observed and remembered, almost not even listening. Clem and My Cellist stood close beside each other, as couples of long standing do – still mostly happy couples, anyway. Clem did most of their talking, perhaps from habit laid down in their early days “back home,” when faulty English fluency, or mid-west accents, might have been a damper on full-throated conversation by both. Or perhaps it was a long-honed meshing of personalities, a mode that worked for them.

As was his nature, and hers, after the first moments Clem and McNeill talked as though they had known each other always. I watched My Cellist, trying to suggest that I glanced back and forth between the two, but really not, seeing only him. He listened intently, nodding agreement, half whispering Oui more than once, tilting his gaze slightly down, focusing on nothing particular. It was not a demeanor I remembered for him from our Paris days; but also not one that he seemed to chafe against.

Standing in my almost isolation, half listening, watching, but only half seeing the now before me, I went back in my mind’s eye to the Madame’s garden in Paris, the room overlooking it where the three of us had known our perfect Paris bliss, not all at the same time, but all in the same place, for a while, long ago. Surely we were still too young to be captured by the old-man longing for that vanished mythical time of youth – and young love.

But no, it would appear not too young for that captivity, not me. Yet even as I yearned a bit for that time, remembered it with a glistening eye, lamented in that sentimental sappy way the passage of that time, and so much other time after it, I knew that I didn’t really want it back; didn’t really want these men back either, though that knowing would be a while in becoming certain. No, the past isn’t past, it’s always with us in the present. But those from the past, escaped from that other world, where we remember them, to join us in person in our present? Are we prepared for them?

I’d thought earlier that we were still the same men, despite the differences time had brought. Now I realized that we were all different, no matter how much the same. The time of us together, however paired, had passed; it was a new time now, and we were different men. That fact, forced before me with the coincidence of our coming together that day, had meaning beyond my understanding then; perhaps understanding would come with time.

I returned from Paris and the garden in time to hear McNeill saying: “We have a symphony in Houston too, and a good one. With chairs open for cellists, I suspect. And as for business, we are booming. The call really should now be, Go SOUTH young men!”

We all laughed at her thrust of humor, and agreed that times had changed.

Calling cards were exchanged. The suggestion floated that we get together for a dinner. But McNeill and I already had a farewell supper planned with Robert; and the next morning we would begin our return drive south. And so we agreed to make the dinner “next time,” in either Chicago or Houston, all knowing the dinner certainly would never be served.

We shook hands again, and parted. And three of us thought back to the Paris we’d always have, so different, no doubt, for each of us. The Paris of that other time, when we were those different men, now long departed.

Loved this segment, it needed to happen.