An Old Man and His Memories: Part 6 - Ah, Russell

Looking Back at a Long Queer Life

(Note: Catch up on earlier parts of the story HERE.)

I took out my list for the day, and checked off the first item: 1. Fetch shirts.

Next on the list: 2. Pay Bills.

The wisdom of age is valued only by the aged, and even for them (even for us – I admit it, I’m firmly one of “them” now), is seldom of any real utility.

The thought flashed through my mind as I sat down at my desk, in what had been our second bedroom, the one used by the one of us who might, any given night, want to be alone, for whatever reason. The room still had it’s single bed, in the unlikely possibility that I might have an overnight guest. Though that had not happened for so long that it hardly even counted now as a plausible reason to keep it. Who was left now to be that guest? A bed with no head to rest in it. A waste of space, especially when adding bookshelves would have been so much more useful. But there the bed still was – and there had been nights, not so many in more recent years, when I’d chosen to sleep there alone myself, when the loneliness of the larger bed next door became too crushing.

I took my checkbook out of the center drawer, and placed it precisely beside the pile of bills to be paid. I always wrote the checks with the gold fountain pen Clem had given me our first Christmas alone again, since those early days, so many years ago, when we’d first been together alone in Paris.

“For writing our memoirs,” he’d said, as he gave it to me.

We both knew that the memoirs would not be just mine and his, but those of all three. Clem and I still had each other: that was the blessing. A blessing destined not to last, of course. But so much of each of us seemed vacant then, when we no longer had Our Cellist. Why does no one tell the young that even the grandest parts of life – like love – are only temporary? Thank God the young would not believe them, even if someone told.

That evening in Mexico City, Russel and I had gone to our dinner, at a festive little restaurant he knew well, on Av. Nuevo León, where he introduced me to guacamole and chilies en nogada, the snow white sauce, scarlet pomegranate seeds, green poblano stuffed with meat and fruit - the glorious colors of the flag of Mexico. And for dessert, flan – cousin of the French crème caramel I’d been so fond of in Paris.

We’d stayed at table for a couple of hours, chatting cordially enough, remembering our shared days and people and memories past, with the lively music of mariachis doing their best to keep nostalgia from curdling to melancholy.

This Russel of one “L” still had his charms, some of them as captivating as those I so dearly remembered in my Russell of years before. He still had his looks, a little older, a little grayer, but no less alluring, taken in by my older, hungering eyes. He still gave off the air of one who admitted lucky others into his aura, and I felt once again flickers of the thrill of being one of the lucky.And yet, that evening the flickers never flared into flames, and, as the hours passed, I came to know that they never would again. Some loves can go on forever – at least as much of “forever” as humans have. Some can fade and then come back again, different perhaps, but as alive as ever. Some, once faded, are best left memories. My love for Russell – without the second “L,” the lost letter only a symbol, certainly, but perhaps a symbol for something irretrievably gone – would, it seemed, be one of those.

He told me that he’d come to realize that he must leave Houston, the life of hands that could not be held in public, and kisses that could only be exchanged in shadows. He’d watched the anguish that Forrest felt, and could not escape; the Kabuki of deflection that Gene and Cardy performed, even before their friends; heard the little lies that we all told the world – even told each other; seen the snickers as we walked past, even at times from those who should have known better. And it had come to feel like a pillow smothering the breath out of him.

He had not told me he was going because he knew that I would do my best to convince him the little lies, withdrawn hands, gasps for breath, were worth suffering to keep what we’d been able to cobble together between us – even in secret, even in shadows, even in shame – a shame so ingrained and so persistent even I could not deny it. He hadn’t told me, because he’d decided that it would be ultimately less painful for me with a quick, decisive cut, which would heal more quickly – like a kitchen cut from a razor sharp knife, instead of a dull one. And a dull one, he thought, a protracted parting would be bound to be.

So thoughtful of him; I could, of course, only be grateful.

When we parted, with a handshake and not a kiss, I walked back alone to my room overlooking the garden, with only a single glance over my shoulder at his receding form, and I almost wished I’d left him, and our time together, entirely in memory. The memories of “then,” though still sweet, would never again be quite as sweet as they had been before. And I would never again think of him, and of us together, without wondering just a little how I could have been so beguiled. A mystery I had not known before that night; a mystery that had not existed before, because my mind could not conceive it until then.

I still had the portrait he’d done of me all those years ago on our day at Galveston Bay – the one I feared then might reveal “too much.” It had been leaning against the back wall of a closet ever so long. I had not looked at it again since I put it there. I wondered what it might reveal now; if it might offer any clues bearing on this new-found mystery. Perhaps I’d take it out and look again. Perhaps.

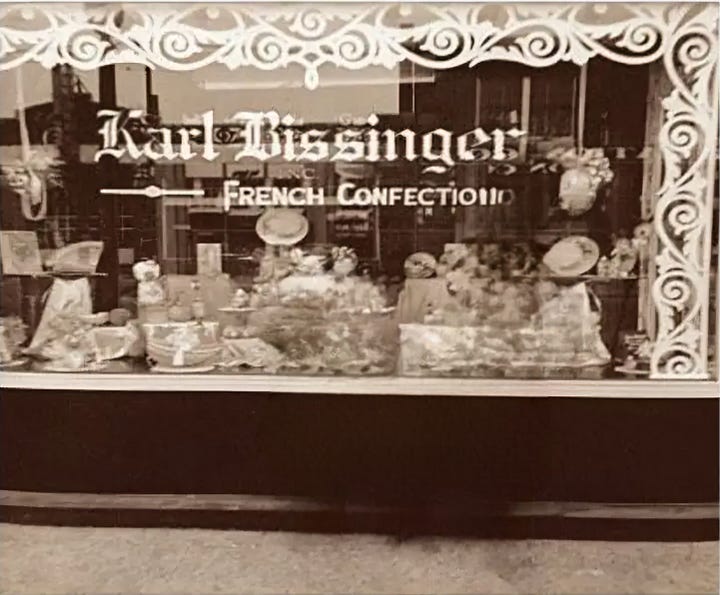

I looked out the window, toward the gleaming Arch in the distance, as I made out the checks for the electric bill and the telephone, Straub’s, where I charged my groceries, and, once again this month, Bissinger’s for the chocolates that made any resolutions about losing weight moot as soon as resolved. I’d be going to Bissinger’s on McPherson Avenue again this very afternoon, in fact, and so could deliver that check by hand. Save the stamp.

And perhaps there, amidst the rich walnut boiserie, surrounded by the mahogany desk for writing love notes on enclosure cards, and the display cases filled with glaceed oranges and apricots au chocolat, I might find some morsel to sweeten the bittersweet taste left from those great loves from the past which sometimes proved not to be quite so great.