How many times can you splash tears across a page before even your most devoted readers grow weary of damp self-indulgence? This is not a rhetorical question. I really need to know. Because it seems that the only stories I have to tell are stories of a past long gone, with tears shed in torrents – or rivers anyway – to wash them forward. A personal past I’d like to call universal. But can any storyteller say otherwise? Aren’t all stories just personal pasts, sometimes repackaged and with different wardrobes? The story of Adrian is just such a story of the past, long gone, but not forgotten – and not to be forgotten for a little longer at least, with luck.

Perhaps Adrian wasn’t perfect – who is? – but how was I to know that at the start? He seemed so nearly perfect, that first time I saw him across the bar, that I could hardly breathe. It was a night like many others in the 1970s, when I was young and foolish – foolish especially about things like love. Some will say it wasn’t love at all, just hormones, but how different are they really when you’re 25? And who, at 25, has the wisdom or the patience to tease out the separate strands? And who, at 25, would act differently even if they could?

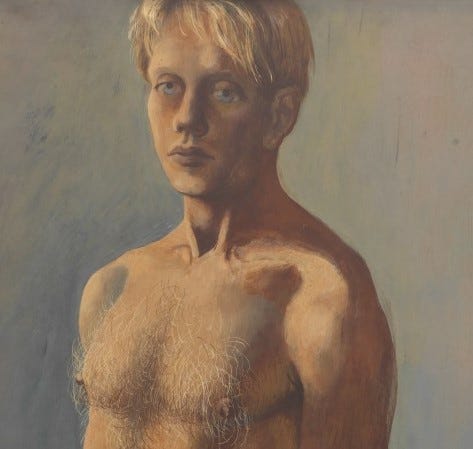

There he was across the bar in his blond glory. Not Greek-god glory by any stretch: not muscled; somewhat slight, in fact. And not movie-idol handsome, but with a broad smile that revealed straight, white teeth (the braces had worked their magic, but were some years gone), eyes that darted and danced (how does one possibly describe what that really means?), and a demeanor that invited in rather than warning off.

St. Louis then (we were in St. Louis) was (perhaps still is – I haven’t been back in years) a smaller mid-western city, with enough gay boys to fill many nights and beds, though nowhere near the inexhaustible numbers of Chicago or New York. Those of us who were regulars at the bars – and I was a regular, no question – became almost a brotherhood. We recognized each other even if we didn’t know each other – though after a while, many of us did know each other in many ways. So seeing someone new was something noteworthy, especially when he was someone so nearly perfect as Adrian seemed to me that night.

I watched him talking to his friends as I stood across the bar drinking my drink – scotch that night, since I feared, even at 25, that beer was making me fat – and calculated my chances of tricking with him. Hooking up may be the more modern term; I’m out of touch about terms these days. But then, tricking was the word – “tricking” for the act, “trick” for the object – and “to have tricked” the morning after goal of every night. But those who said it had all, or even much, to do with sex knew not of what they spoke. The sex was a minor element in the greater scheme. It was the chance for love that kept one going against the odds. How many dozen, hundred tricks before the love appeared? Perhaps this would be the one. How many times had that been said? And how seldom true? But sometime. It had to be.

After a while Adrian’s eyes danced toward me. That’s how I saw it, and though I might be wrong, I wasn’t ready to admit it yet. His eyes danced away and then danced back. That couldn’t have been accidental. Such accidents don’t happen in gay bars, or didn’t then – I’m not sure how the world works now. It could be that things are different now. Because this is a story of long ago; and, be warned, there will be tears.

He seemed to beckon me with his smile – that’s the way I saw it, anyway – and I was eager to be beckoned. Then came the old familiar sequence: the walk across the bar; the “Hi, how are you?”; the glances back and forth; the laughter, a little strained at first, then easy and comforting. It took only 15 minutes to be sure what the next stages of the sequence were to be: “Let’s get out of here.”; “Your place or mine?”; the walk through the crisp early autumn night to the apartment just up the block on Euclid; all the steps and starts and touches that made it the first night of all the many that came after.

As we lay in bed the next morning, with golden sun coming through the window, I looked over at him and he opened his eyes. I smiled and he smiled, and I reached out a hand to touch his chest. It may not have been a perfect moment, but it was as close as moments get to it.

We went on seeing each other past Halloween, more and more as the weeks went by. The maples turned red and orange and dropped their leaves one by one. On their appointed day, after the first hard freeze, the ginkgoes turned golden and shed all their leaves “in one consent.” We planned a Thanksgiving feast together, with some dishes from his side and some from mine. Together we decided who we’d invite. As Christmas approached, and the temps grew colder, we lingered longer in the mornings before heading home. Some days – weekend days, when neither had to work – there was only time to check the mail and change before getting back together for the night.

One Saturday the snow began to fall almost as soon as the sun went down, and continued falling all night long. By sunrise it was inches deep – in some corners close to feet. But there was no wind, so it wasn’t a frenetic fall; the cover was spread across the ground like icing contoured on a cake, swooped and swirled in spots as though by the swipe of a spatula, but mostly smooth and angelic white.

We woke to crystal skies and the fearsome clanks of radiators only just waking up themselves. We woke regretting our lack of foresight at not getting the Sunday New York Times the night before. Reading it together in bed on Sunday had already become our undeviating ritual. That morning we flipped a coin to see which one would pull on flannel shirt and jeans, gloves and boots and stocking cap and coat, and trudge through the snow to buy it from the newsstand in the Chase-Park Plaza. The loser dressed; the winner lay naked amidst the sheets, promising coffee and cooked breakfast (and maybe more – certainly more) as reward.

And soon there were Christmas presents, and red and white candy canes, and a tiny tree, from the Goodfellows lot on Delmar, decorated with twinkling lights and strings of popcorn and cranberries. It was just all too wonderful – too perfect – to be true. Or, as it happened, to last. (Be warned, this is where the tears begin.)

One day there was no getting back together. It didn’t seem so big a deal; it just made sense that day – at least to one of us. Yes, tomorrow, certainly. But then tomorrow came, and still it wouldn’t work. Something had come up. No big deal. Later in the week for sure. We could use a little time apart – to let our hearts grow fonder. Though how a heart could be fonder then mine already was I couldn’t fathom.

The problem with perfection is that it’s never real. We all know that in our minds, but not our hearts. (Maybe not even in our minds.) There’d been a time when I touched him for no reason but to be sure that he was there. In those early days I wrote my friend, Claudia: “I think I’ve found him. I’m trying not to jinx it by believing it’s really true – but some days, some nights, I can’t help myself. I know you’ll understand the terror that comes with the thought of love. What can be more perilous than finding what you’ve always sought?”

She did understand because of our long love, the kind that lasts because it knows it’s limits. It’s that love that knows no bounds – the kind that holds the possibilities of ecstasy and devastation – that surpasses understanding, or even explanation – the kind I had for Adrian – that wise lovers stay wary of. And yet, at 25 how many can maintain their guard against it – how many have even the desire to try, never mind the steely resolution?

In January the winter set in in force, and that year it was a winter of the heart for me as well as a winter of the seasons. Of course I asked what had changed, what had gone wrong, and of course he had no adequate explanation – adequate for my understanding that is, since I was the one left grasping. I can’t say that I was surprised, because it was a play I’d acted in before, more than once, though with slightly different wardrobes and other stars. So who was the fool here, if there was a fool? Maybe there wasn’t one. Maybe there was just someone – two someones – trying to get by as best we could – trying to get by with no guidebook to chart the way through treacherous terrain.

“Man trouble again,” I wrote Claudia, and she understood.

After the winter, spring came as it always had, and so as I always knew it would. Oh, yes, there had been tears – I warned you there would be at the start, and knew it too – that likely there would be. The odds were always in their favor.

“To have loved,” I wrote Claudia, “though not the morning-after goal, and scant consolation, makes a gossamer bridge to what will follow, whatever that will be.”

What I loved most about spring back then were the blizzards of pink petals the breezes blew from the flowering trees. It was as though the winter pain had drawn just a drop of blood to mix with the angelic snow, to turn it pink. Fall-winter-spring that year was Adrian’s Arc. It wasn’t perfect by any means – was rather short, in fact. And yet for a little while it was as close to perfect as such things are, perhaps as they can be. And so the tears – the ones I warned were coming – were not, are not, tears of regret. But oh how they flowed and how damp they made the page, when that season of Adrian had expired.

It was over far too soon to suit me, but then forever would have been too soon for me. Perhaps such perfect things – as close to perfect as such things get – can only last a season, then must go. Perhaps that’s a law of nature. Here for a little while, then gone. Though not forgotten so not gone entirely – memory and tears (now tears for lost years as much as lost loves) have seen to that.