Molly, A Gay Romance and Dog Story:

But With No Happy Ending - a St. Louis story of the 1970s

Molly was some kind of terrier, a little yappy dog with too much energy and an annoying talent for taking center stage all for herself. But that’s the way dogs are, I suppose, so I shouldn’t have held it against her. And I didn’t, really, except that she made herself the center of his attention too, and so I was jealous. There’d been a time, not all that long before, when I’d been the center for him, and I missed it. I guess it was cowardly, though, to blame the dog for my downfall, when I should have been blaming him – or maybe even myself.

It started so perfectly. We met on a summer evening between hot spells, when the temp had cooled to delightful, and the dusk sky had cleared after a late-afternoon rain. The showers, once they’d washed the air and cooled the day in St. Louis, had moved further south, following the river toward Ste. Genevieve, leaving the evening balmy in the city – balmy enough to make a drive south, to the watermelon stand at Gravois and Chippewa, a temptation too enticing to resist.

After dinner – and a few drinks – and maybe a few joints – we crowded into Bob’s car – six of us, Bob, Sheila, Leon, me, and two of the cute young guys who so often were part of our group (not always the same two, and whose names I so seldom remembered for long). We drove south down Kingshighway, from the Central West End, where we fancied ourselves to be edgy sophisticates bringing the gay abandon of the 1970s to our decaying dowager of a city. We were conspicuous, if not completely out of place, in South St. Louis – Bob with his diamond studded ear, Leon in his wine-velvet dinner jacket, stick-thin Sheila with her Fiorucci jeans, so tight she had to lie down on the floor and suck, suck, suck it in to zip them up. The rest of us, in our clone-ware looked almost tame. We drove down past Tower Grove Park, and still further down into the heart of the greaser south, as far from sophistication as could be.

There we were on a summer evening, sitting on folding chairs at folding tables, under the trees in South St. Louis, bright strings of lights swaging from limb to limb making it a poor man’s Tivoli Gardens, with large slices of chilled watermelon on paper plates before us, red/green/black-flecked, like a Rivera painting. Was there music? I don’t remember. Maybe the love songs of cicadas singing in the trees. There we were, flamboyantly out of place, but relishing the strength-in-numbers defiance of simply eating melon in such an alien environment – reveling in it. Across the yard, other tables of other groups, some neighborhood, some interlopers like us, all with the same intention: to enjoy an evening of respite from the hot summer, before the hot summer returned tomorrow. On such an evening there was hardly an empty table.

I cubed my melon carefully with knife and fork, and let the luscious, cold, wet cubes linger in my mouth as I savored them. And I looked at the other melon-eaters, doing the same in their individual ways. As I ate and savored and surveyed, I caught sight of his brilliant smile flashing my direction from where he sat with his group a few tables over. Not that the smile was for me, any more than for everyone. But the brilliance of it, and the sparkle in his eyes that accompanied it, made me long to think it was for me as much as anyone.

I ate and watched and half listened to the gay repartee of our little expeditionary force. I laughed and nodded and tossed in my own sparkling bon mots from time to time, but truth be told, my attention focused exclusively on him, as though I’d been mesmerized by a sorcerer. Without cubes of watermelon to fill my mouth, it would have hung foolishly open, I suspect. Maybe it did anyway. Others noticed. One of the cute guys at our table (I don’t remember which), said, “Oh, I know him. He’s hot.” No offense, cute guy, but what a ludicrous understatement.

The watermelon stand wasn’t the sort of place you’d expect to find a trick back then – not to mention a lover. But I did. Cute guy walked over to say “Hi” to him. And taking pity on me, perhaps, invited him to join us. He sat down in the empty chair beside me, and smiled that brilliant smile – this time most assuredly for me. I offered him a cube of melon, since he’d left his behind. He took it off my fork, into his mouth, and my heart pounded – drowning out the cicada love songs, for my ears anyway.

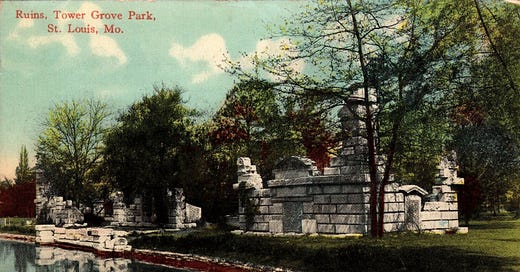

I know we talked. We must have talked. But I have no more recollection of what we said than I do of cute guy’s name. But the actual words are no more necessary than the name to my memory of the meeting – and what happened after. Words enough, at least, were spoken – or maybe unspoken – to take us together out of the watermelon stand, and to his car, and on to his apartment, on the front side of an old house on Magnolia Avenue, overlooking Tower Grove – the palm house and the music stand, and the ruins surrounding the pond – ruins salvaged in 1867 by Henry Shaw, for his new city park, from the conflagration of the Lindell Hotel, then the largest hotel in America, reduced to smoldering “ruins” in hours. Maybe I should have taken them as an ill omen for our love. But that first night – or rather, that first morning after, as we strolled in the park, past those very ruins, around the pond, with the early cool still lingering over the soon-to-be once again summer-hot city, I couldn’t imagine ill omens – or conflagrations – though too soon, the heat of our love would (perhaps was always destined to) burn hot enough to burn itself up, and our hearts – at least my heart – along with it. But not yet.

First there’d be the passion of summer Sunday mornings in his apartment, in his bed: passion, so often a dressed up name for porn in modern stories, but so much more. And the fun of September Saturdays at Soulard Market, where the pie lady never disappointed, with her fruit fried pies, and her sweet potato pies, “so good to the taste and bad for the waist” – but even at 28, who cared on such splendid mornings? Later, the glorious beauty of fall drives up along the Mighty Mississippi, just as the leaves were at their flaming peak, to Elsah, on the Illinois side, and then back across the Golden Eagle Ferry, with the dash-dot-dash Morse Code of afternoon sunlight across the surface of the river. And the bliss of holiday feasts and Christmas decorations shared with each other, and with each other’s friends.

But it's so much easier to write about heartache, and make it plausible, than it is about bliss. Bliss, like Tolstoy's happy families, always seems the same, and cloying. Heartache, though truthfully also always the same, maybe, seems to each of us unique - and makes our suffering unique too – even while sympathizing, harmonizing with tales of others’ heartaches, even that of those we'll never know. And so I’ll pass quickly through our bliss (and our passion) of summer turning into golden autumn, over looking our park, and then of new snow greeting us on December mornings. I’ll go to January and February – the cold heart of winter. By then our bliss had changed to bitterness, and Molly’d joined us, soon to be the one of us who’d still be with him into spring.

Why the change, when the bliss had been as brilliant as his smile? That’s the grieving lovers’ question for the ages. I had what seemed like ages myself to ponder it, through those bitter winter days, and then the bleak spring and barren summer that followed, after he ended it.

No question, he was the one who ended it. I doubt that I could have even if I’d wanted to. Any fool can manage beginnings. I’d proved that often enough. But it takes courage, or at least steely nerve, to take command of endings. I possessed neither when it came to love, or at least the end of it.

I intended, when I started, to stop this tale of heartache at Flash Fiction’s 1500 words. I’m already there, and haven’t yet written anything that explains anything. But what more is there to say? It ended. I left. Molly stayed. I looked back and saw her in the window as I departed (he wasn’t there). I wasn’t jealous of her anymore; I never had been really. I’d miss her. I’d miss him. And I’d miss the bliss he and I had for a while, and the passion – enough to take me past 1500 words – but not enough to last forever, as it turned out – if I ever really thought it could.