(Note: This is my second interaction with a poem by Emily Dickinson. Click the title, We Will Remember Him, to find the first one.)

Wild nights - Wild nights!

Were I with thee

Wild nights should be

Our luxury!

Futile - the winds -

To a Heart in port -

Done with the Compass -

Done with the Chart!

Rowing in Eden -

Ah - the Sea!

Might I but moor - tonight -

In thee!

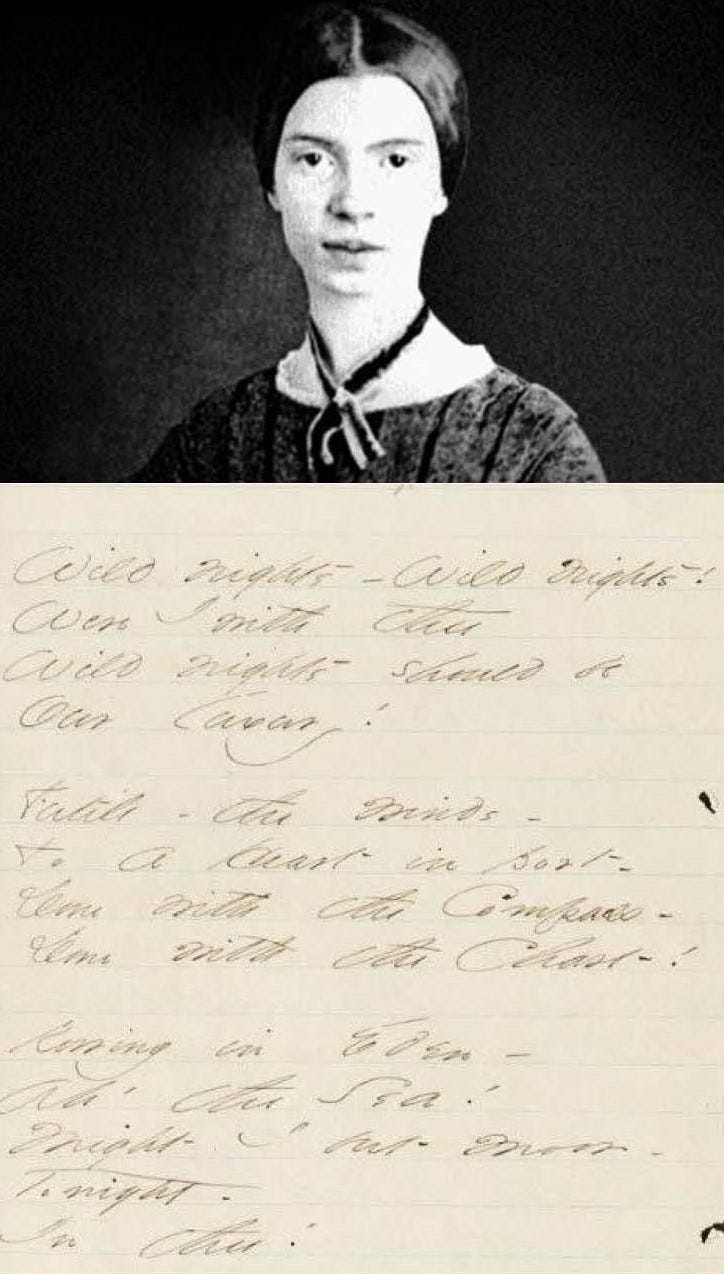

Wild nights don’t depend on drinks or drugs – nor loud music and dancing crowds. She had no experience with such things – we’re told. But that Dickinson could even write the phrase – and repeat it – is the wonder. And that I do. Young virgins and old men shouldn’t know about things like that – or shouldn’t admit it if they do. But young virgins, some of them, have imaginations, and old men have memories, and wild nights – sometimes the wildest – can happen in both those realms.

We suppose that her wild nights were all imagination, though we can’t know that for sure. And that she did write the phrase, and repeat it, suggests that she may have known more than we suppose. My own wild nights, now long ago, were at a time when compass and chart were not so much done with as unknown. Mine were gay wild nights in the 1970s: there were no charts or compasses for most of us to help navigate those wild seas. And there were drinks and drugs aplenty, and discoing crowds.

But back in those days, when we were young, and hopeful that we were going to find our mooring – the true mooring for those like us, which was not the one we’d so long been told, those were wild nights worth risking.

Rowing in Eden is not the phrase that first comes to mind to describe those nights. Though they were paradise of a kind, for young men like me, who had each always thought we were the only one, and that God despised us for who we were. To find, after the explosion of Stonewall, that we were not alone – that there were armies of us – and that we were not abominations – was an atomic discovery unleashing energy that had been stifled for eternities.

So why wouldn’t the nights be wild, as we sailed that tumultuous sea, our hearts in peril more often than in port. And yet still there was the longing, which she says so well (certainly she knew more than we think): Might I but moor – tonight – in thee! But he (or she, or they – there may have been multitudes, for all we really know) must have existed, not in imagination only for her. I won’t name mine either, though they existed too – now just in memory, but then in flesh.

Let me be clear: since those days I’ve found my mooring, have known the comforts of a heart in port. I wouldn’t, by choice, return to those wild seas; I’m too ancient a mariner now for that.

Even though those wild nights are in the past for me, confined to memory, so not completely gone, since still remembered, there are still wild nights of a different kind – which may be the kind that Dickinson clearly knew so well.

The problem with poems, even beautiful ones – maybe those especially – is that they can obscure more than they reveal – or they may reveal so many possibilities they overwhelm us. That’s the case for me with her 43 wild words in 12 wild lines. If I were made of sterner stuff, perhaps I wouldn’t be undone by such a slight thing. But I’m not; and I am.

In some sense I’ve become as much a monk as she was the “nun of Amherst.” But monk or nun, as we may be/may have been, the nights can still be wild, the winds can still blow gales. She knew that; she tells us so. Our wild nights may be different, or they may not. But with her few words and lines, she reassures: we’re not alone in the wildness, or don’t have to be. She’s there with us, if we let her be. And we’re with her. Together – our luxury.

c.1861/2024