Why Research Houston’s Art History?

Especially for Houston Art History Groupies

“When I first arrived in Houston in 1981, to curate exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, I was shocked to find that the museum had never held an exhibition of a local artist.” Barbara Rose, 2016

Wasn’t I shocked – shocked because the statement is incorrect – to read this first sentence in Barbara Rose’s Foreword to The Color of Being/El Color del Ser: Dorothy Hood, 1918-2000 (Texas A&M University Press, 2016), the splendid book by Susie Kalil, published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name mounted by the Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christi?

As a devotee of the Houston artist Emma Richardson Cherry (1859-1954), I knew for a fact that MFAH had mounted exhibitions of her work, and also of many other local artists. Those exhibitions may have been much too long ago for my satisfaction, and perhaps not quite frequent enough, but they had happened, and I would have expected Rose, a prominent art historian and critic who served as senior curator at MFAH from 1981 to 1985, to know better.

A quick count in the exhibitions listing of Alison de Lima Greene’s Texas: 150 Works from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH/Harry N. Abrams, 2000) turned up more than 40 solo or duo exhibitions of local artists at MFAH by 1981, when Rose arrived. And there were also many group shows with a strong representation of local artists, like the juried Houston Annual exhibitions (1925-1960), limited to residents of Harris County, the Texas General exhibitions (1940-1964) and the Southern States Art League circuit shows of the 1920s and 1930s.

I point this out not to reflect badly on Rose, who, along with co-curator, Kalil, mounted one of the most enduringly significant (even if sometimes mostly as a focus of criticism) exhibitions ever mounted of Houston artists, Fresh Paint: The Houston School, (MFAH, 1985). I point it out because this discrepancy between belief and fact is a stark example of why it’s important to find out more about Houston’s art history.

I’ve been having something of a crisis of purpose lately. After all the effort and energy that many of us in the HOUSTON EARLIER TEXAS ART GROUP (HETAG)/CENTER FOR THE ADVANCEMENT AND STUDY OF EARLY TEXAS ART (CASETA) community have expended over the years, now turning into decades, with what sometimes seems like little impact, I’ve begun to wonder if it’s really worth it. The years are getting by; we may not have that many left; is this how we should be spending them? Is it perhaps time for us to wise up and accept that what we’ve been doing may not be that important? (Oh, my, how unsettling those middle-of-the-night musings can be!)

I’m writing this, of course, because I’ve concluded that it is worth it, and Rose unintentionally helped me get there.

Yes, there have been exhibitions of local artists at MFAH, going right back to the beginning. Not as many as some of us might like, and not nearly as frequent as should be, in my opinion, especially in recent decades, but they happened, and without finding out the facts – which is to say, researching the history – we wouldn’t know it.

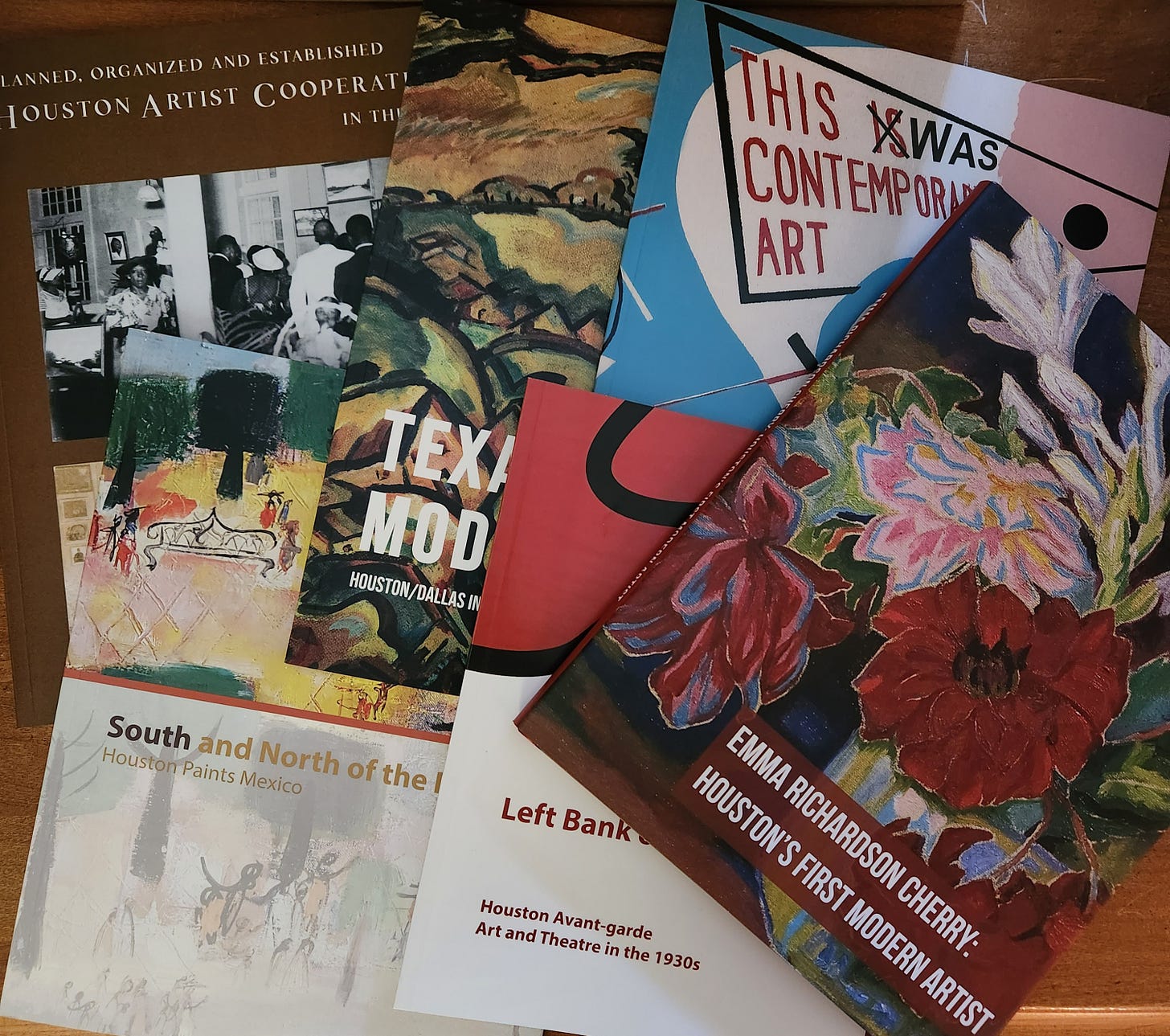

Without doing the research, we might also accept the myth that there were no galleries in Houston, or none that mattered, before the 1960s. But there were galleries going way back, and they were showing local artists: Yunt Gallery, as early as 1922 and going right through the 1930s; Little Gallery in the late 1920s; La Vielle France in the early 1930s; The Cottage Gallery in 1934/35; The Browse About Shop in the mid-1930s; McNeill Davidson’s Our Little Gallery of abstract art in 1938; and The Houston Artists Gallery, a cooperative run by the artists themselves, spearheaded by Grace Spaulding John in 1930 and active in various iterations until 1938. (Note: An exhibition focusing on the Houston Artists Gallery and a parallel organization of black Houston artists, the Negro Art Guild, was on show in the Ideson Gallery of Houston Public Library, August to November, 2017.) These galleries, and a number yet to be discovered, did exist long before the 1960s and they made a difference.

Without doing the research we might accept the assertion that modernism, when it finally got to Houston, arrived as the largesse of a few enlightened collectors (Ima Hogg; John & Dominique de Menil), that our artists had nothing to do with it. Indeed the collectors may have been enlightened, but it wasn’t the collectors who painted with Marsden Hartley in 1920 (as Mrs. Cherry did); it wasn’t collectors who brought the first Cubist paintings to Texas in 1926 (Mrs. Cherry again, and they were paintings she painted herself in Paris); it wasn’t collectors who filled Maholy-Nagy with “wonderment” when he saw the young Robert Preusser’s work in 1939 (according to McNeill Davidson’s description of the event). With due respect to Ima Hogg, one of the earliest Klee collectors in America (influenced in Klee’s direction by Mrs. Cherry, I’m pretty sure) and the De Menils, who had a momentous impact here, the artists were doing it first – they just didn’t have as much capital or as much publicity. Studying the history can uncover that truth.

This is important not just to get the facts right, important as that is, or as a matter of pride. If we believe that our local museums have never supported local art, then why should we expect them to start now, and really why should they? If we believe that our local artists were always behind, why bother looking at what they did and judging for ourselves, or expect that our contemporary artists are any less so? If we believe that there were no galleries (because there was no art worth showing? because no one cared?) why should anyone bother looking at the art our place, Houston, has made over the centuries?

History is only living memory unless someone digs further back, and what we think was true about the past is likely wrong unless we’ve done the work to find the facts.

When we’ve done the work, the picture of Houston’s art history is different from the one that has prevailed for decades, and it’s immensely richer. The flourishing art culture that has developed here didn’t begin from nothing in 1950 – basically the beginning of living memory now. Because we’re digging out that history, we know that there were artists making art here, galleries showing it, and institutions collecting it far back into the early 20th, and even the 19th, centuries.

Houston isn’t New York, Paris or L.A., but it doesn’t need to be: those slots are filled by New York, Paris and L.A. And Houston art isn’t theirs either. All art is local at some point, and artists, like writers, have impact when they create from what they know. The past is part of that. Until we know our own art history, whether we’re artists, collectors, museum professionals or just interested viewers, and realize that we can learn from it and take pride in it, even if we choose to break with it, we don’t stand much chance of discovering the local uniqueness that might have a broader impact.

Rose may not have known the history of art in Houston. If she had, the groundbreaking exhibition she mounted with Kalil would probably have been even more significant. And she certainly would have started her Foreword in the Dorothy Hood book with a different first sentence, I hope. Perhaps something like this: When I arrived in Houston in 1981, I was shocked to find that the art of the city was exciting and varied, and that it had been so for a very long time–and I was eager to build on that history. (How comforting some middle-of-the-night musings can be!)

One reason we moved back to Houston--the lively art scene and the people who were (and are) made it happen.

Thanks again! a great and informative read.