The Story of a Love That Didn’t Last

A St. Louis Story of the 1970s

FIRST WE MET

The day was hot and humid, as so many Saint Louis summer days are. I lounged by the pool at Executive House, letting the sweat and the pool water (from occasional cooling dips) glisten on the hair of my pretty-good chest and pool in the naval-reservoir in my pretty-firm stomach, inches above the top edge of my red Speedo (where a hint of pubes escaped, as though seeking some adventure of their own).

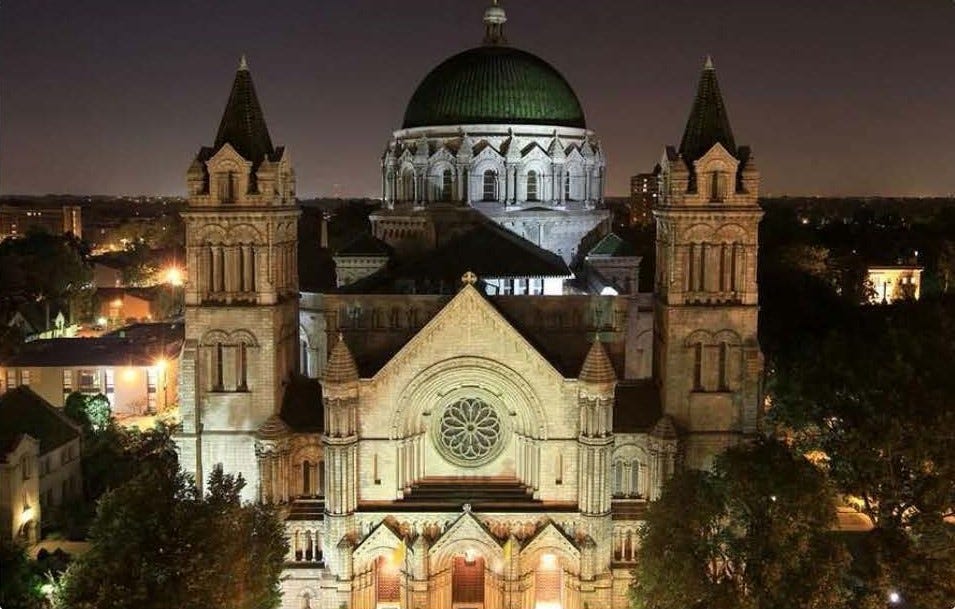

I didn’t live in Executive House. I lived across West Pine at the Hawthorne, which had no pool. It was my cello-player friend, with whom I’d had a brief affair (now over), who’d invited me for the day – the one whose social-worker lover had picked me up in Forest Park on a day in the spring, for an afternoon of delight (only one). Neither cellist nor social worker let those peccadillos – or a comical three-way attempt – quash friendship, once we’d all accepted that it would be a friendship without “benefits.” And so I lounged around the Executive House pool at their invitation, and with the use of their 17th floor apartment – views east to the Arch, and north over the Cathedral dome – for cooling off, or cooling drinks, or other, hotter things.

Basting in the roasting sun, I turned over from time to time so that any who cared to could see both my pretty good front and my pretty good (and pretty welcoming) behind. It must have been a Monday, because cellist and social worker were both at work; and the large, in both person and personality, restaurateur, famous for his way with chicken, for his kaftans, made with yards of flamboyant, flower-printed fabric, and for his 4-H entourage (handsome-hunky-hung-horny), was not.

That Monday, HE was part of the entourage. I’d never seen him before, that I recalled: sometimes it’s hard to be sure in the bright light of day who you might have seen, and maybe been smitten by (or not), in the bright lights of discos. I was pretty sure, though, that I’d never seen him before.

It was almost as though a scene I’d written years before – completely derivative – a scene from a piece I’d titled “Siegfried Idyll” out of some homage to a Wagnerian ideal with which I had no heritage, of which I had no knowledge, had presented itself before me:

His hair was golden in the spring; his skin was ivory. With each sunny day his hair bleached paler, until by fall it was almost white. And as it paled, his skin grew darker. By September they had reversed: his hair was ivory, and his skin gold. He stood, poised like marble, an aura (was it perfection?) spreading around him like breath.Well, his hair was golden. He wore a gold chain around his neck and a white Speedo around his “ivory loins” – with his own hint of adventure-seeking pubes. We looked at each other across the pool – not with Walt Whitman’s “swift flash of eyes,” but with the penetrating, calculating, stripping-bare gaze of young gay men in the 1970s, not that the Speedos, red and white, left much that wasn’t stripped bare already. But still, a gaze “offering me love,” as Whitman said – or what might pass for love on a summer afternoon.

THEN WE WERE TOGETHER

Pass for love it did, that afternoon and others after. We went up to the apartment for something cool to drink, followed by many much hotter things. We had all afternoon, so felt no need to rush. By the time we’d finished what passed for love, and napped and showered and finished again, the bedsheets were a jumble, our lips and tongues intimate acquaintances, and we’d explored every contour, crevice and opening of each others bodies with our hands and other parts.

After the nap, I woke up first, and looked over at him. He breathed softly, his eyes shut, his soft cock lying amongst those pubes which had found their adventure. What luck we’d both chosen that summer Monday to spend around the Executive House pool - a spur-of-the-moment decision (on my part, anyway), that put me in mind of fate.

I looked out the bedroom window at the Cathedral dome and downtown St. Louis. I lit a cigarette and took a deep drag, and looked back at the napping demigod (what foolishness and tripe the first rush of love tempts one too) nestled in the disorderly sheets. He opened his eyes; we looked at each other and smiled; I bent down and kissed his sensuous lips, and neither of us minded that the shower still lay ahead. The lingering scents of sex reinforced the certainty we both felt deep inside that something grand had happened – something that would go on being grand into the future, for both of us.

That was our first afternoon of love together. Nothing unusual; there had been other afternoons, with others, in that same apartment, in that same bed – the bed I stripped and remade, as a good guest does, so that my generous hosts-in-absentia would have no reason to regret their generosity. I smelled the sheets – I could still smell him on them – as I put them in the washer. That was part of the generous agreement; that, and the tacit understanding that some hints of why the sheets needed washing be shared – nothing too coarsely explicit, just delicately detailed enough to spur imagination – a three-way (no, four-way) a step removed.

But this time I didn’t share, or even hint at, the detail that really mattered: that this time had been different, unusual, because this time there had been so much more than sex – so much in addition to sex – this time there’d been a feeling along with the fucking that I could only think of calling “love” – not that loose usage that made love-in-the-afternoon a laugh-line for gay dinner party badinage, but the kind of love that thrills, even as it scares a fellow shitless.

Before he left, we exchanged numbers – one always did; it seemed only polite after fucking, even when both knew neither would call. But this time both knew we would call; and we did, almost before either took time to think how over-eager such rash and rapid calls made us appear. I invited him for dinner, and he accepted. He suggested a movie, and I said yes. It didn’t matter what or when or where, it only mattered that whatever, whenever, wherever, we were together. This was the early stage of love, which swept all before it, even recollections of other early stages that had come before – and hadn’t lasted. The recollection of those didn’t even arise for months and months – or at least weeks and weeks.

He lived in a Soulard row house, near the market, not the Central West End where I had my apartment; and he’d only recently come to town, which explained why I’d never seen him. I had no car, so when we stayed at his, I almost felt kidnapped and dependent on him to say when it was time to go back to my CWE world. Of course, sometimes we stayed there, even though my top-floor Hawthorne studio was small, with only a single bed. In those early days of love, sleeping two to a twin presented no problem, since sleeping entwined made the bed seem big. And, to tell the truth, sleeping often hardly entered in.

This went on into the fall. We both stopped going to the Executive House pool – gave up the easy afternoons of casual sex it represented – after that first one we’d shared – and, though the sex between us was easy, it was anything but casual, almost from the start.

He was the one who said out loud what we’d both been thinking: “I wish you wouldn’t go there – without me.” And I’d replied without a pause: “I don’t even want to – without you.” And I meant it. What we had was what I wanted; even strange cock, new ass, formerly so fascinating, lost their allure.

I did introduce him to my Executive House friends, and we all had dinner together only feet from the bedroom of our afternoon delight – and there were dinner party hairpins about where we’d met and when – nothing coarsely explicit; just enough to let everyone know that everyone knew – and that it was fine with all. I touched his hand at the dinner table, and then his cheek as we stood looking out at the Cathedral dome, while our hosts cleared the plates. That hardly counted as anything sexual, but for us, at that stage, sex saturated everything, and our hosts, glancing at us as they cleared, may have looked at each other and longingly remembered when that had been true for them as well – a long time ago. I put my hand on his ass, and moved closer, and our hosts called us for coffee.

In September we said “I love you,” and it was true.

WE HAD OUR BLISS

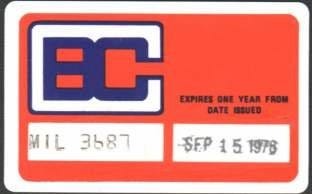

Between Thanksgiving and Christmas we fled an arctic blast for a week in sunny Key West – flying into Miami on TWA, and then renting a car for the drive through tropical paradise to the glorious, warm, magical end of the road. We stayed at chic, cute Island House, where the gays played. Though we both had our Club Baths membership cards when we met, and though we both had used them, both cards stayed behind in icy Saint Louis – that’s just how into only each other we both still were, even after all those months. We laughed that maybe we would go to the tubs, and then be only with each other just to make the New York fairies envious. But in the end we did all our being together alone.

If our love had a shelf life, it was a longish one, and we were still an item (no, too trivial; still a couple) at the beginning of winter. The Soulard row house was drafty for the season, but a fire in the fireplace, and down comforter and flannel sheets for the bed, helped. In each others arms, we managed to stay warm enough. The Hawthorne radiators clanked at times, but insured there’d be heat, even as the twin bed grew a little small. I offered to buy a futon – offer NOT accepted – even as he mentioned once or twice come morning that he’d had a hard time sleeping.

AND THEN WE WEREN’T TOGETHER ANYMORE

Perhaps that was when the ascent of love began to level off. Or maybe it was when he got word that his job in St. Louis was ending (he was an architect with a big initials firm) – that he’d be moving elsewhere for a new assignment. It was the first time the practical world forced entry into our oh so impractical world of love. He told me about the impending move at the end of a long Sunday afternoon of lovemaking – the end of yet another perfect weekend which had started with an early, frosty Saturday morning visit to Soulard Market, and had taken us through cooking and eating and discos and drinking and Sunday morning paper reading. A weekend which, except for the buzz-kill of the news, would have been one of the best weekends we’d had by the time he drove me back to the CWE and the Hawthorne, where we would spend the night making more love – and planning for even more weekends. But the news took it’s toll, so the weekend was not quite among the best.

The lovemaking continued – intensified even, if that were possible – as though it sensed an end was stalking it. No, this was not going to be an end, he said. We were going to make this work. Somehow. If only we could be a proper man and wife. But we were man and man. Even in the (almost) anything-goes 1970s, there wasn’t much place for man-and-man in the practical world.

Make it work. Somehow. But how? That became the practical question; as it turned out, the question for which we could not (or would not, or anyway, did not) find an answer. The time came when he moved to Chicago. Not so far really (but far enough). I stayed behind – vowed to make the trip between the cities often; we both did. And for a while we did, though month-by-month the time between the visits lengthened. Even in the impractical world of love, which we still managed to live in once in a while, we couldn’t manage to find a path for the long term. Olives were not fiction. We found no “greenwood” where Maurice could take his Alec, where two men could “fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows,” as Forster puts in his Afterword.

So love didn’t last, not for these two men, for us, not then. But wouldn’t it have been nice if it had? So nice.