The Space Between Looking and Loving, Echoed:

Me and Charleston, the Bloomsbury Country House, and an Exhibition at the Menil Collection

Recently, I had the pleasure of exploring the exhibition, The Space Between Looking and Loving: Francesca Fuchs and the de Menil House, at the Menil Collection, in the company of artist, Francesca Fuchs, and curator, Paul R. Davis. It’s a subtly complex exhibition which requires much more from viewers than many museum shows – much more than just looking at all the pretty pictures – though there are several of those.

Because of that complexity I won’t presume to summarize it, except to say that a discovery in her father’s archives revealed to Fuchs, by now a long-time Houston resident, an unknown connection to the de Menils, from long before she ever came to Houston herself, through one of the objects in their vast collection. Which took her on an odyssey through the de Menil archives and collection and house to find meaning in that connection, and in the connection they, and many of us, have to the objects we choose to bring into our lives, our imaginations and our homes.

As I looked at the paintings, photographs, sculptures and other objects, and listened as Fuchs talked about her art practice, and as both of my guides talked about the evolution of their project, I realized I was experiencing a connection to an exhibition such as I have seldom had - hearing echoes of a similar journey I’ve taken over many years, completely unrelated to the Menil show except in concept. I came to understand that journey of my own in ways I had not had the tools to articulate till then.

(For the following couple of paragraphs I play fast and loose with extracts from the gallery guide to the exhibition, available on the Menil Collection website; please forgive me, artist and curator, for my liberties here.)

“Her work pulls objects into a compelling narrative that signals an objective truth of representation and a subjective faith in recognition and memory. In the space between looking and loving, the authenticity of objects and their surrogates intermingle, and time collapses.”

In making her art throughout her career, Fuchs “… has made paintings of objects from her home: family mementos, curios, framed paintings, prints, and photographs – whatever their art historical significance.” She employs the “… excavation and re-presentation of objects …” and “… continuously reworks … until she recognizes the subject’s essential objecthood …” to discover the “… personal and relational histories of objects in domestic settings …”

For the current project, Fuchs has employed her “… studied remaking of objects through the transformative power of painting ...” to delve into “… the de Menils’ ‘affair with’ or love of art.”

In their exhibition, Fuchs and Davis present old photographs of the de Menil house, original objects, including paintings, and Fuchs’ “re-presentations” to make their points.

Some phrases in the above spoke loudly to me:

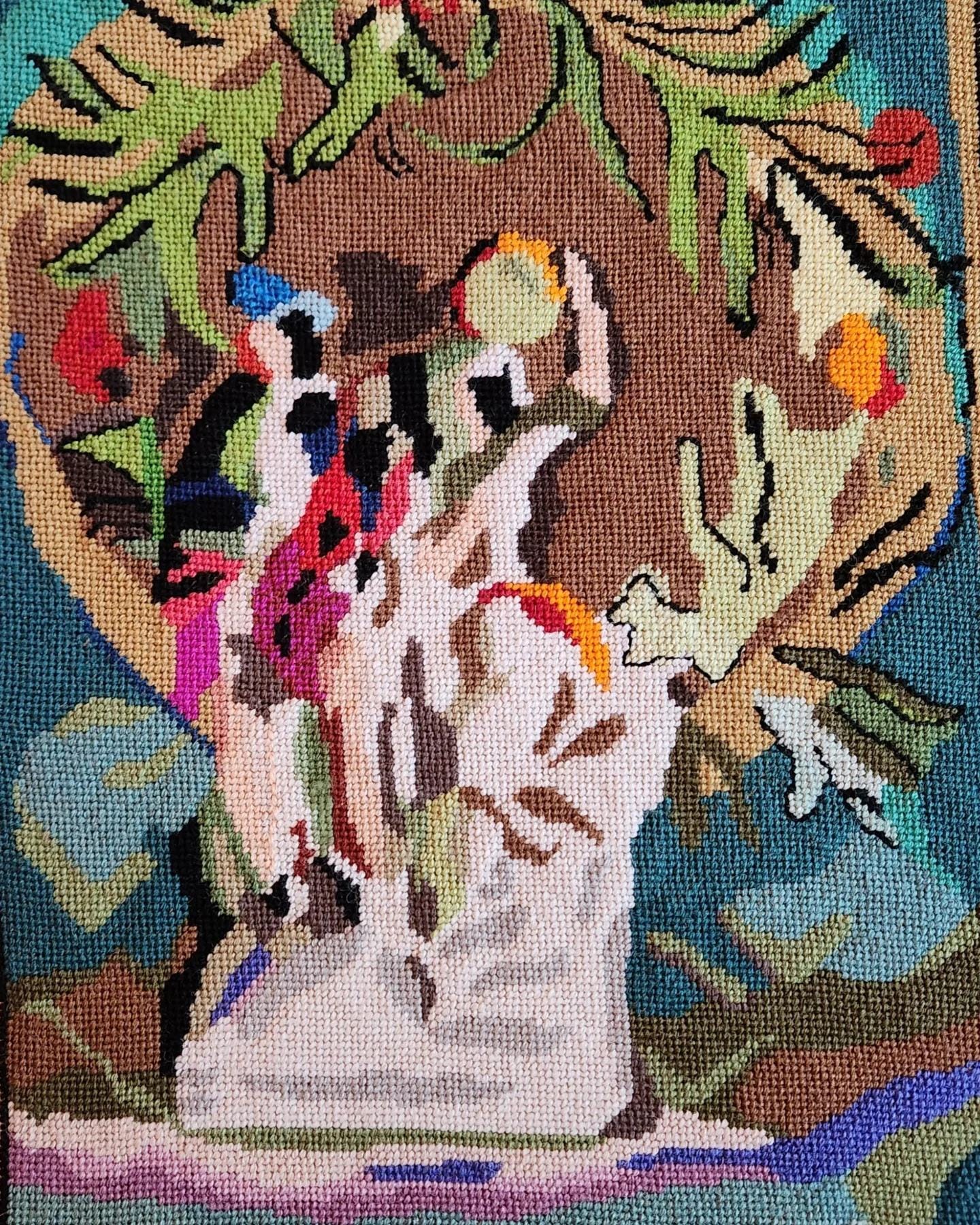

“… excavation and re-presentation of objects…” Could that mean “copying” objects discovered? Wasn’t that what I’ve been doing for some time in my needlepoint “re-presentation” of paintings and drawings by others, “whatever their art historical significance[?]”

“… the authenticity of objects and their surrogates intermingle, and time collapses.” Wow, I know that feeling when I can hang one of my needlepoint “copies” beside the “original” it “re-presents.”

And, the “… studied remaking of objects through the transformative power of painting …” Make that “the transformative power of STITCHING” and suddenly maybe I don’t have to apologize anymore for making the needlepoints I do. Could it be I’m attempting something that even real artists do, and I just didn’t realize it till now?!

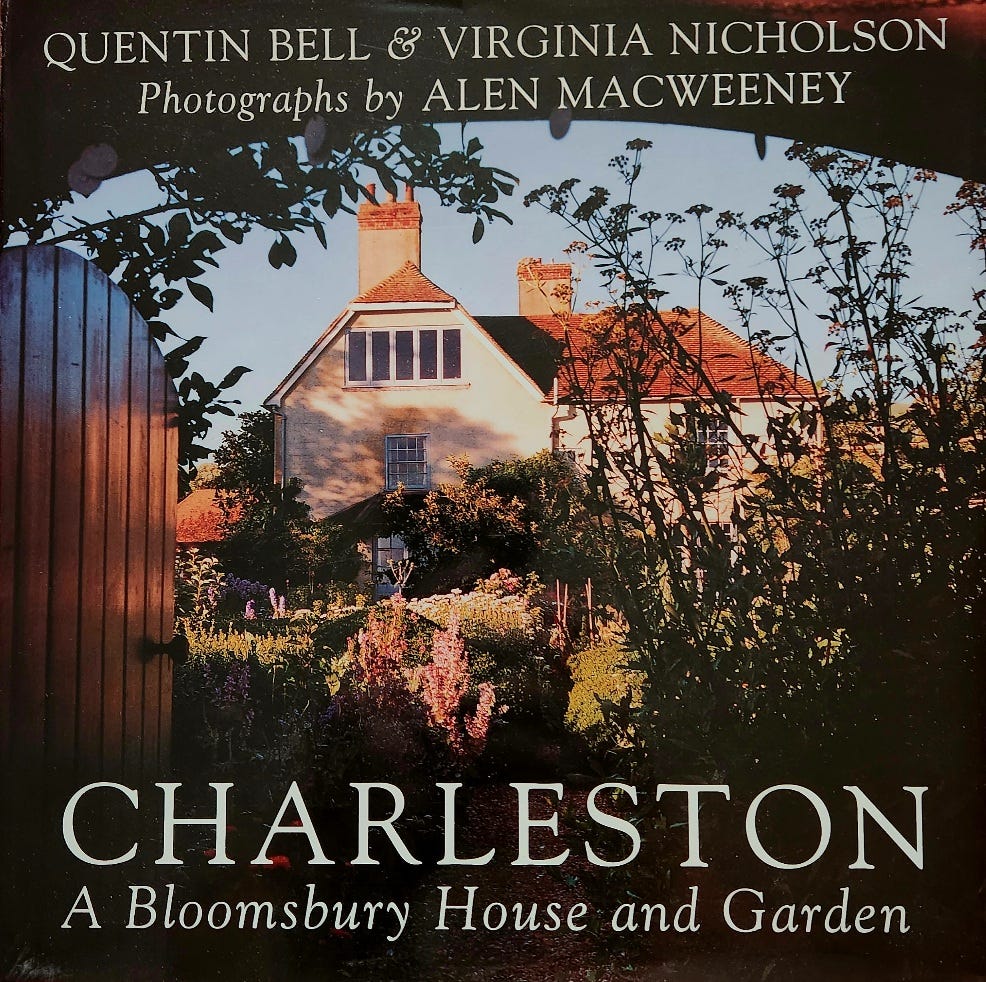

All this is a cumbersome prelude to a brief look at my relationship to a house I’ve never visited, Charleston, the Sussex country house of the avant-garde artists, writers and intellectuals of the early 20th Century Bloomsbury group in England.

Some of their names may be familiar: Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell, her sister, Virginia Woolf, Roger Fry, Lytton Strachey, John Maynard Keynes. I’d heard about them in college and after, since they had quite a vogue in the 1970s and 1980s. I’d even read some of them: Woolf’s novels, of course, Strachey’s Queen Victoria, a little Keynes (grudgingly) in an economics class. And I’d seen some of their paintings, though not many, since few American museums have them. They piqued my interest especially when I discovered in my “excavations” that many of them were queer, a discovery made just as I was making that discovery about myself.

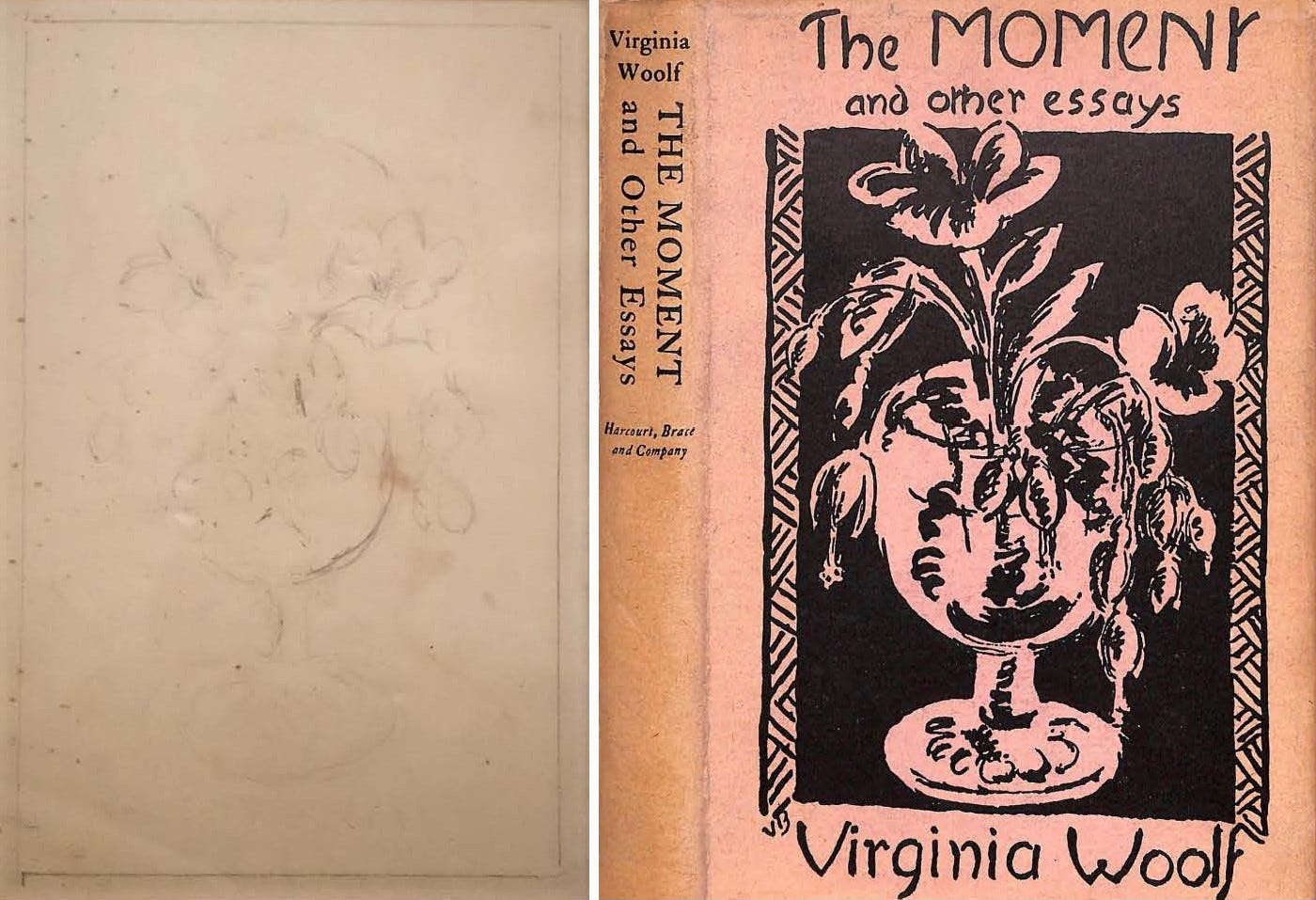

As part of a collection of artist-designed book jackets (most now housed at the Hirsch Library, Museum of Fine Arts Houston) I’d already acquired Vanessa’s delicate pencil drawing for the jacket of The Moment and Other Essays, by her sister, Virginia.

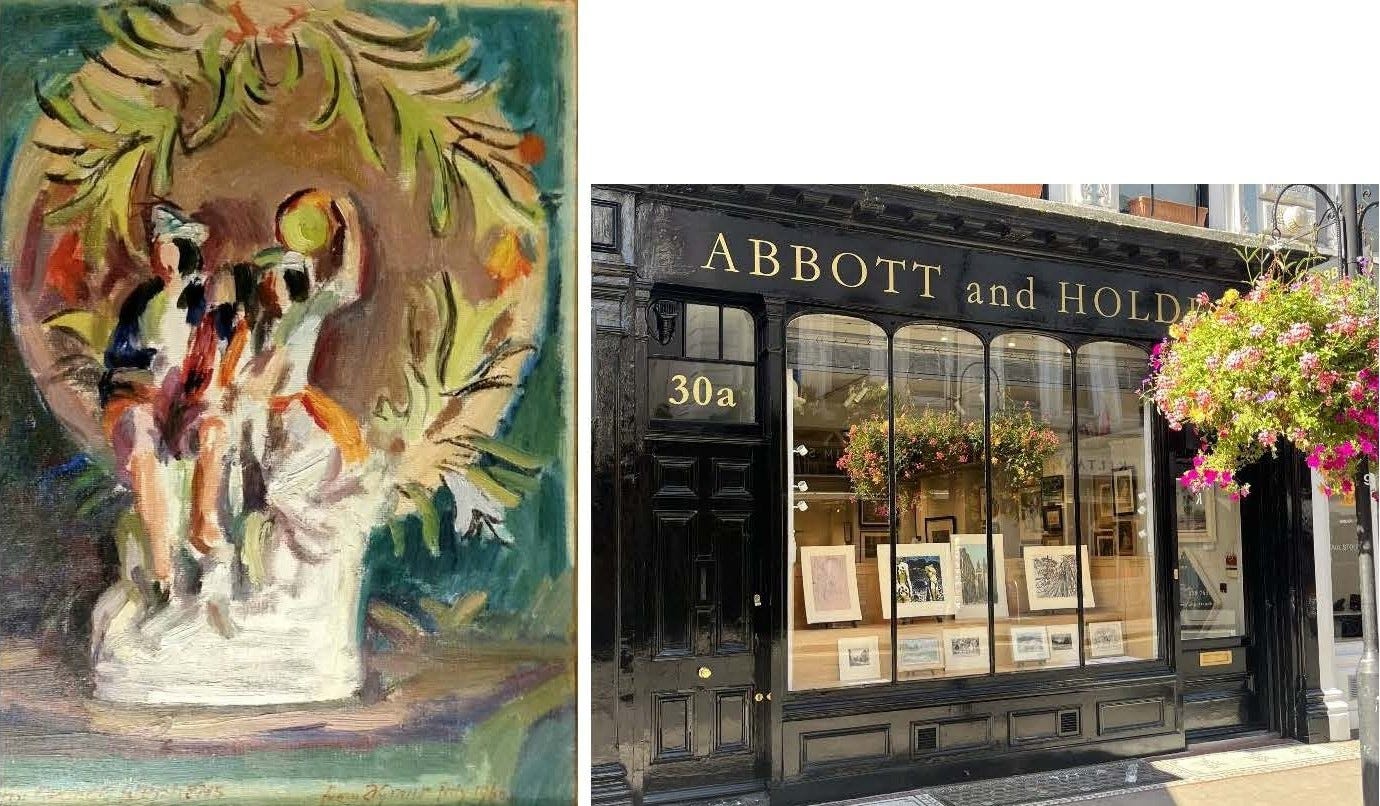

But I really only became aware of them in a personal way through a chance encounter one summer day in London in 1996 (like Fuchs’ de Menil discovery in her father’s archives?), after a visit to the British Museum, when I walked by the shop of the “Picture Dealers” Abbott and Holder, a few doors up Museum Street, and spotted a lovely, colorful little painting in the window, which drew me inside.

It turned out that the painting was by Duncan Grant – yes, that Duncan Grant – and to my surprise, the price was in a range I could conceivably manage. So I bought it and brought it back home to Houston, where it has hung ever since, joining that Vanessa Bell book jacket drawing.

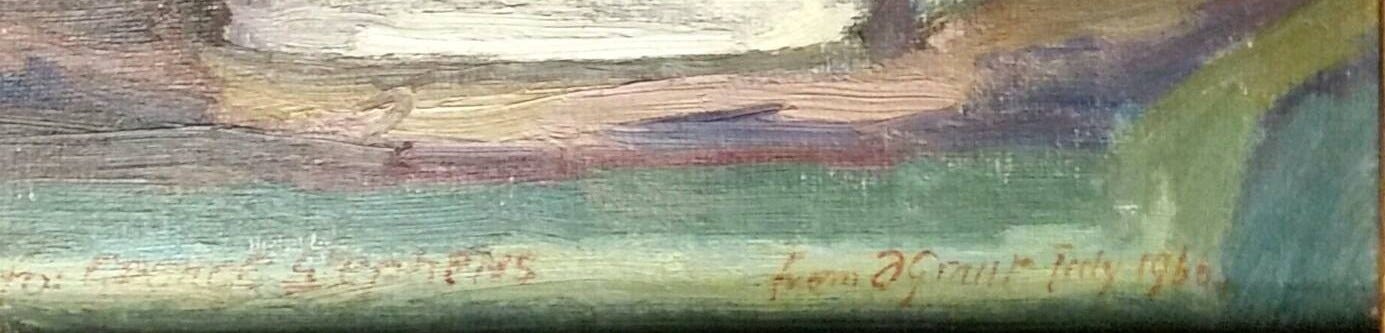

The painting is signed “for George Stephens/from DGrant July 1966.” At first I thought that George might be a relative of Vanessa, based on his family name. Closer looking proved me wrong: she had been Vanessa Stephen, without the “s.” And in fact, George turned out to have been the gardener at Charleston – no relation, but a vital member of the household since gardens made (and still make) an essential part of the whole when it comes to English country houses of a certain vintage.

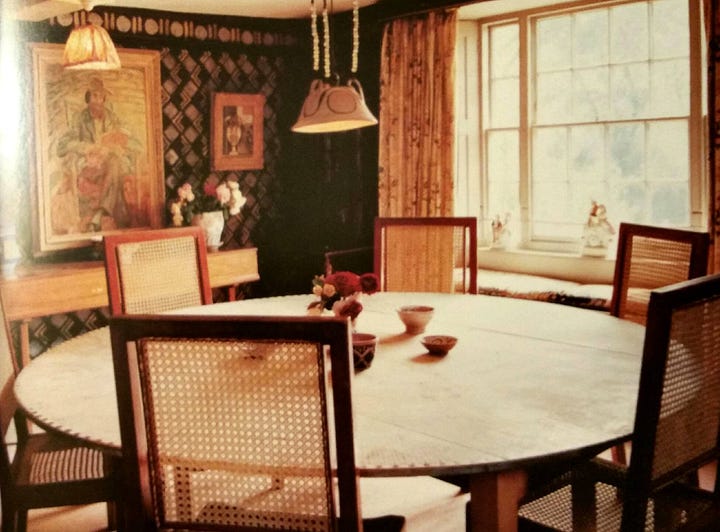

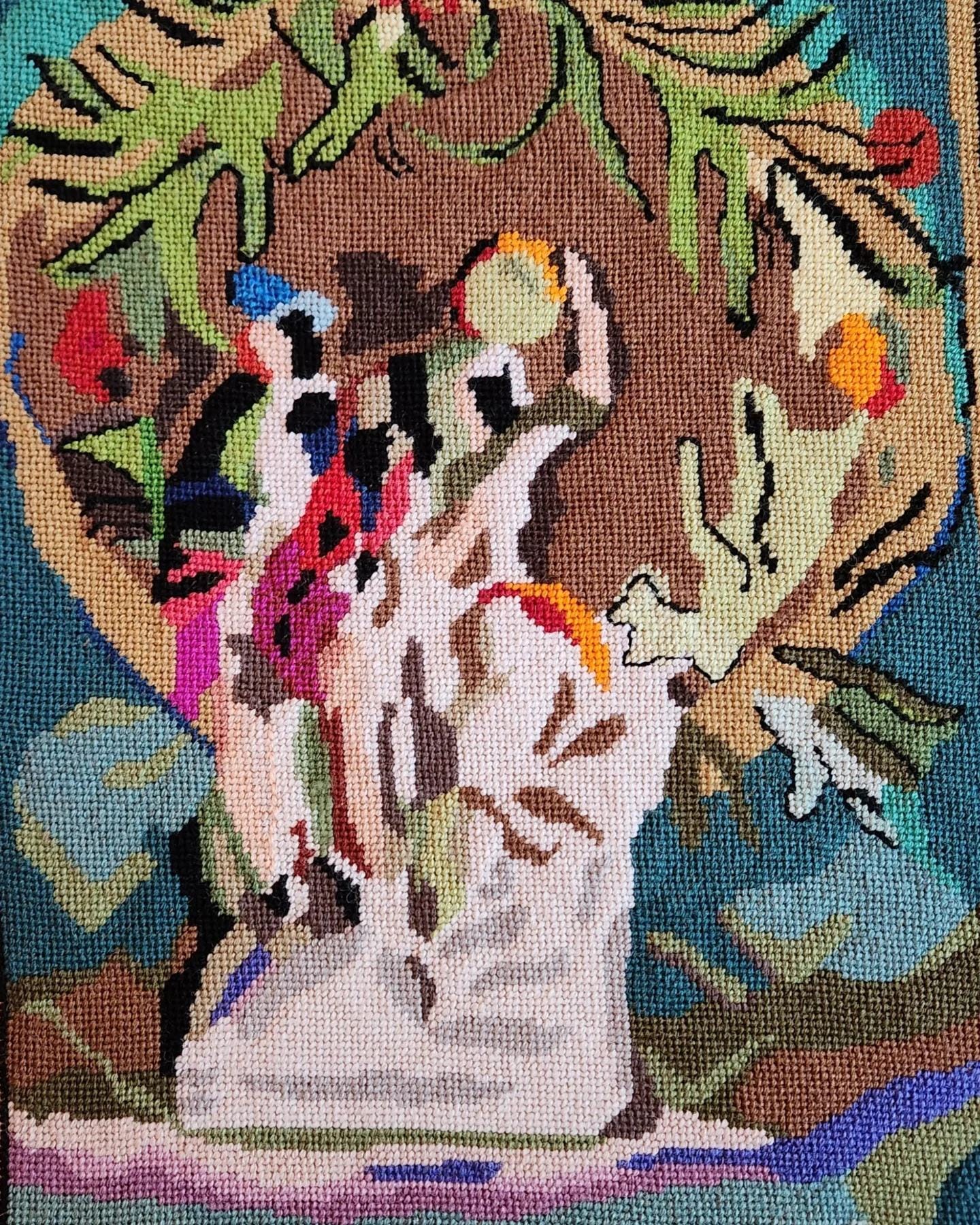

In an effort to find out more about the painting and George Stephens, I mailed off a letter to the curator at Charleston, who sent me a cordial reply confirming that Stephens had indeed been the gardener there once upon a time. And further, that the subject of the painting was a Staffordshire figure group that still had its place on the window sill in the Charelston dining room – the very window through which Grant, and all the Bloomsbury residents and visitors, had looked out at the garden itself, out there, just over the shoulders of the Staffordshire lute strummer and tambourine tapper who had serenaded their festive country meals. Why, I almost felt as though I sat there with them, hearing the music and enjoying the garden view!

And when I needlepointed, based on the painting, “re-presenting” the Grant painting in which he had “re-presented” the Staffordshire figures on his window sill, I stitched for some compelling reason I couldn’t then even articulate – but I knew I had to do it. (Thank you, Francesca Fuchs, for helping me begin to articulate it now).

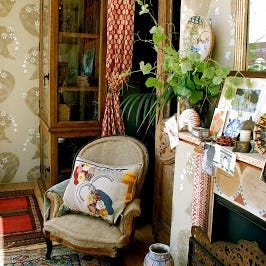

And it didn’t stop there. Another photo, this one of the Charleston sitting room, included a tapestry cushion I found irresistible, tucked into an easy chair, obviously often sat in, perfect for cozy afternoons reading Virginia’s novels, or maybe those of E.M. Forster, a sometimes Charleston visitor. Forster’s Howard’s End lay miles away in Hertfordshire in his novel, but only inches distant in spirit.

Vanessa probably stitched the piece, based on a design by Grant, or one of her own – or maybe someone else did the stitching and/or the designing – there’s no knowing for sure, since, in their Omega Workshop, cooperative effort ruled the day. I found that I had to “re-present” that cushion too, and bring it to my home, and me to theirs, in some degree, through stitchery.

And then, when COVID Lockdown came along, and I did my series of IMAGINARY DINNERS, I included both pieces in one of the installations – the one titled TEA WITH THE QUEEN (so not technically a dinner). See the cushion at back left, and the painting, back center. Note, also, the Queen Mum commemorative plate, bought on another trip to London, and the QE2 sugar cookies – make that, biscuits – with ruby and silver crowns. (I still have the biscuit cutter!)

I’m not at all sure what all this means, if it means anything. But I do know that touring The Space Between Looking and Loving with Fuchs and Davis got me thinking as few museum exhibitions ever do. And got me writing, even though I probably don’t really know much of anything that I’m writing about. But it’s been fun (for me, at least), and a great opportunity to share more of my needlepoint.

If you get to Houston between now and November, be sure to see the exhibition at Menil. And maybe even stop by for TEA with the queens (tee hee) for a look at the Bloomsbury “re-presentations” here.

Thanks for this fascinating post about this exhibition at the Menil - am now motivated to make sure that I see it !