Solitary Afternoons

A St. Louis Story of the 1970s

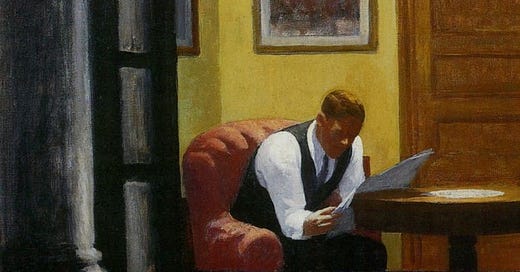

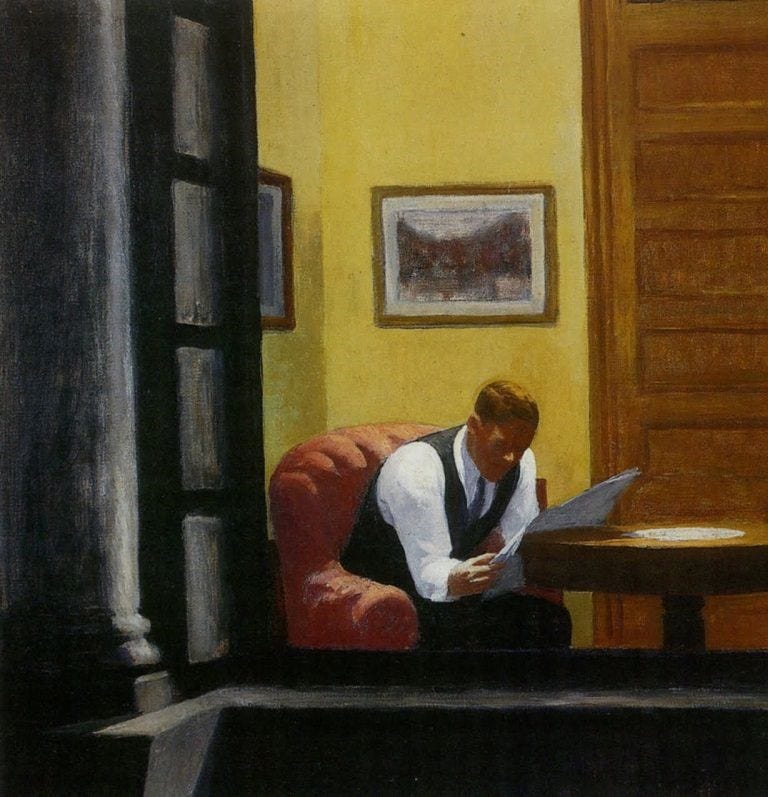

The sun had begun to set, a bit more grandly than usual – befitting Sunday. The fading rays struck brilliant oranges and pinks from the drifting clouds. They cast a last bath of golden light on the tops of houses and trees, and gave a gold liquidity to the atmosphere of the streets and alleys running toward the west. The descending orb made a magnificent dowager of the day, which had shown little potential for magnificence before. The beauty of it surprised me as I sat holding a book only half read, and that half only half absorbed. I closed the book and set it down, failing to slip in the flowered mark which lay on the table beside me. It didn’t matter; I wouldn’t likely get back to it. It had served its purpose, had given me a mercifully legitimate excuse for passing the long afternoon alone.

Solitary afternoons are luxuries – if they’re chosen. If not, they have a way of seeming endless.

My lover had left – had told me that the love was gone, and the thing had become rather a burden and a bore – that we’d best separate. I agreed to the separation. I had no choice, so I agreed. Though none of what he said held true for me. So we separated, and now I spent my evenings, my nights, my interminable Sunday afternoons alone.

I walked into the bathroom and looked at my body in the mirror. Slim; firm. Slimmed down, firmed up consciously in the hope of keeping him in love – an unappreciated effort, apparently; certainly an unsuccessful one.

For the fourth time in as many hours, I showered. Nothing soothed me more than warm water engulfing my body – nothing, aside from Valium. I’d showered so much since the breakup that my skin had dried and developed a sheen of flaky white, like the film on last-season apples. I’d showered three bars of Dove soap to slivers. My hair had never been cleaner, nor my dandruff more flourishing.

Two years had passed since we’d met – well, almost two. I called it two for convenience when anyone asked. We’d never lived together. First one had wanted to, and then the other; never both at the same time. Some obstacle had always arisen to keep us living apart. But we might as well have lived together. For two years (well, almost two) we’d eaten every dinner, slept every night, drunk every cup of morning coffee together. Though at the end, it was better we lived apart, simpler. We had no common property to divide; neither had to find a new place. We had only to exchange a few shirts, a few pairs of underwear, and return each other’s keys. So easy. Now I wondered if we’d both been planning for it all along, expecting it – not consciously, you understand, but planning none the less.

I looked out my window at the huge clock looming above Highway 40: 6:15. From my window on the 17th floor of the Hawthorne, I had a view over miles of South Saint Louis – Barnes Hospital, State Hospital, Deaconess Hospital, and, squatting beside it, the Arena. My lover lived just beyond the Arena. Former lover. I still only remembered the “former” as an afterthought. I refused to say “ex,” which sounded so final. He lived way over there in a little duplex he’d bought (or rather, one his father had bought for him) on West Park Street. We’d spent many passionate nights and lovely Sunday afternoons there together. Now I supposed I’d never be going there again.

I drew the curtain across my window. From every corner of my apartment, ferns and fig trees begged for water. Dust reveled in inattention. Piles of dirty clothes lay about, limp sentinels of desolation. The songs I heard on the radio didn’t help: “You’re My World” “I Honestly Loved You” “I been cheated, been mistreated ...” Still I listened, to help fill the void.

Earlier, my friend had called. “Hi, how are you?” “Can’t complain.” “You don’t sound too chipper.” “Cold coming on.” “Oh, too bad. Everybody has colds now. I just got over one. How about you two come to a party tomorrow night? Think you’ll feel like it?” “Can’t promise. Might be worse.” “Well, if you feel like it. About 8. Take lots of vitamin C.” “Oh, yeah.” “Love to you both.” “Bye.”

Someone else could tell her. Someone would. Saint Louis was small enough, our friends entangled enough, that someone would be bound to spread the word that we’d broken up. Then she’d feel bad that she’d called not knowing. I was sorry for that, but I was nowhere close to being able to decline invitations to both of us, or accept invitations only for myself. I wondered if he felt the same. No, he wouldn’t. Breakups don’t work that way. Separations, I mean to say; maybe it wasn’t really a breakup.

I thought maybe I’d get dressed and go out. Nowhere in particular. Anywhere. The crystalline sunset of a cool fall evening glistened outside. A shame to let it go to waste, since hot-humid-dirty or cold-grey-bleak days outnumbered the glistening ones twenty to one.

I put on my best shirt and my best pants and looked at myself in the mirror. The shirt molded to my chest and my newly muscled arms; the pants fit snugly around my slim waist and my butt. I didn’t look bad. Pretty good, in fact.

But dressing up for no one is more depressing than not dressing up at all. Besides, I’d tried it just last night: put on the same best shirt and pants; looked at myself in the mirror; walked up West Pine to Euclid, up Euclid, past Lindell, Maryland, Pershing, Hortense, to McPherson, toward the bar.

Up from the corner I’d seen his car parked in front of an apartment building. Seeing it set my heart thumping. Nothing about it had changed: the front plate still hung loose on one side; the beige upholstery had not grown any dirtier, cracked any further. Familiar items, some of them mine, still littered the back seat. The soda can I’d put on the back floor the month before, as we drove up from Mobile, was still there. A new item, a theater program, lay in the passenger seat, another on the floor. I looked at the title and remembered the tickets, one of which I’d bought, for the play the night before. That was the trouble with relationships – buying tickets two weeks ahead might be too far. At least it hadn’t gone to waste; someone had used it. But it hadn’t been me. I’d turned and walked back home.

And today I changed back into the home-clothes I’d had on before. I wouldn’t go out, even though the evening was beautiful. Sometime in the future, of course, I would, but that would be a while yet. Now I lay down on his side of the bed and wondered why it was that an effort at love could prove so ineffectual. Nothing I could think of doing had been left undone, nothing left unsaid. In the end, nothing had made a difference. My lover had left me, for all I’d done and said, and now I spent my Sunday afternoons alone. Even the beautiful ones.