Return to the Locked Psych Ward

Still Crazy After All These Years

I know it’s not permissible now (and it shouldn’t have been then either) to talk about the loony bin, cuckoo’s nest, nut house – and there’s nothing funny about the also problematic funny farm. But “Locked Psych Ward,” its formal name in the hospital where I did my time, sounds so clinical, so lifeless, so sane. And most of the time things were hardly sane for any of us there, patients or staff, it didn’t matter which.

After college, I spent two years in the Locked Psych Ward of Deaconess Hospital in St. Louis – 1971-1973. Deaconess isn’t there anymore, gobbled up over the decades by hospital vultures, downgraded and diminished bite by bite, finally demolished in 2014. But it was a big deal back then.

They told me I worked there, an orderly performing alternate service as a conscientious objector. Some days I bought the “working there” line; some days I saw through it as a devious ploy to make me a more docile patient. Either way, it was a post-graduate education for which History 101, and even Advanced Psychology, had not prepared me.

It was a small ward – 36 beds, two to a room, ranged along two corridors going off the dayroom, with the Nurses’ station in the center so that no room was more than a minute’s sprint away. Emergencies of the psyche can be as critical as those of the body, and can need as lightening-fast attention.

Our ward was what’s called “short-term” – three weeks max. If it took longer than that to “fix” patients, they had to find another locked ward somewhere else, for longer stays. Which meant we had mostly people in crisis who would likely soon, after our tune-ups, be returning to the lives that had thrown them into crisis to begin with – and would likely take them back to crisis soon enough once they went back to them. And so, in my two years, I became almost friends with several of our short-term regulars, who came back to us time after time.

If you’ve seen One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest you may have some image already of what I’m describing. We didn’t have our Nurse Ratched, though I’m sure some of the patients thought otherwise. I remember the prophecy of a patient during my first days there, as I tried to comply with his demanding, and unending, requests: “You’re new here. Give it a week, and you’ll be just like the rest!” But I think most of the staff had good intentions, even if toughened for self-preservation over time. The sort of sinister seeming night orderly did make me a little uneasy, but in fact probably for no real reason: 40 years of working the night shift, 11-7, in a locked psych ward isn’t the best prep for vivacious social interaction, perhaps.

In addition to the rooms and the Nurses’ station, there was also a small kitchen, for making and dispensing pacifying snacks throughout the day. Eating is a great diverter. After a while, I snagged the coveted evening shift – 3 to 11 – when most of the serious action of the day was done (in theory, anyway), and the patients mostly just needed occupying until lights-out at 9 o’clock. I baked many dozens of cakes and cookies in that kitchen in two years. And bore the guilt of many added pounds – not added to ME, since I was young, gay and discoing every night after my late shift, so stayed thin – but, oh, the hip and thigh augmentation of the patients! I spent my evenings baking, and taking blood pressure readings and censuses of bowel movements. And I knitted many a useless strip of “thing,” sitting with patients who had little else to keep them occupied as they tried knitting selves into garments they’d fit into, no matter how many stitches they’d dropped.

But my life in the locked ward wasn’t all sugar and spice and purling, I assure you, even after I moved to that “tranquil” evening shift.

Like making sausages, making sanity, or at least a semblance of it, isn't pretty. You really don't want to watch, especially if you're not one of the sanity makers. Maybe not even if you are.

First there was that locked door. Even though I had a key, I can’t forget the clonk, and the queasy stomach that came with the sound, as that heavy wooden slab, with its massive metal lock plate, and tiny plate-glass window – wire mesh between the plates – closed behind me as I came on the ward that first day. The door was locked for the safety of some patients who might wander off if doors were open – and for the safety of the world when it concerned others of them, who were not going gentle into their awful nights, wherever those nights were taking them.

One of my routine duties at the start of each evening shift, after making sure the door had locked behind me, and then greeting everyone, both staff and patients, on my walk down the hall to the nurses' station, for a status update (who was doing well, who'd had a rocky day, who might be volatile through the evening), and a bit of casual back-and-forth with other staff - nurses, aides, even doctors, if any doctors were still there so late in the day (usually a bad sign if they were) – was to saddle soap the leather straps to keep them supple.

I took the cloth and rubbed it in the tub of “soap” (more like wax than foamy soap) and then pulled it down the straps one by one, as they hung in the workroom by their buckles from hooks, like thick leather belts six feet long. I did this every day - unless they were “in use,” had been “applied” – which meant, of course, that someone had lurched alarmingly away from gentle, and now lay strapped in his bed. It always seemed to be the male patients to whom the “restraints” needed to be “applied.”

Even in that time of blunter lingo, and like Locked Psych Ward instead of “loony bin,” we called them “leather restraints” instead of “straps,” and putting them to use was “applying the restraints,” not “strapping patients to their beds.” Though those euphemisms were not the terms we used amongst ourselves: no one was fooled by them – especially not the applied-to patients, nor those of us directly involved in the applying.

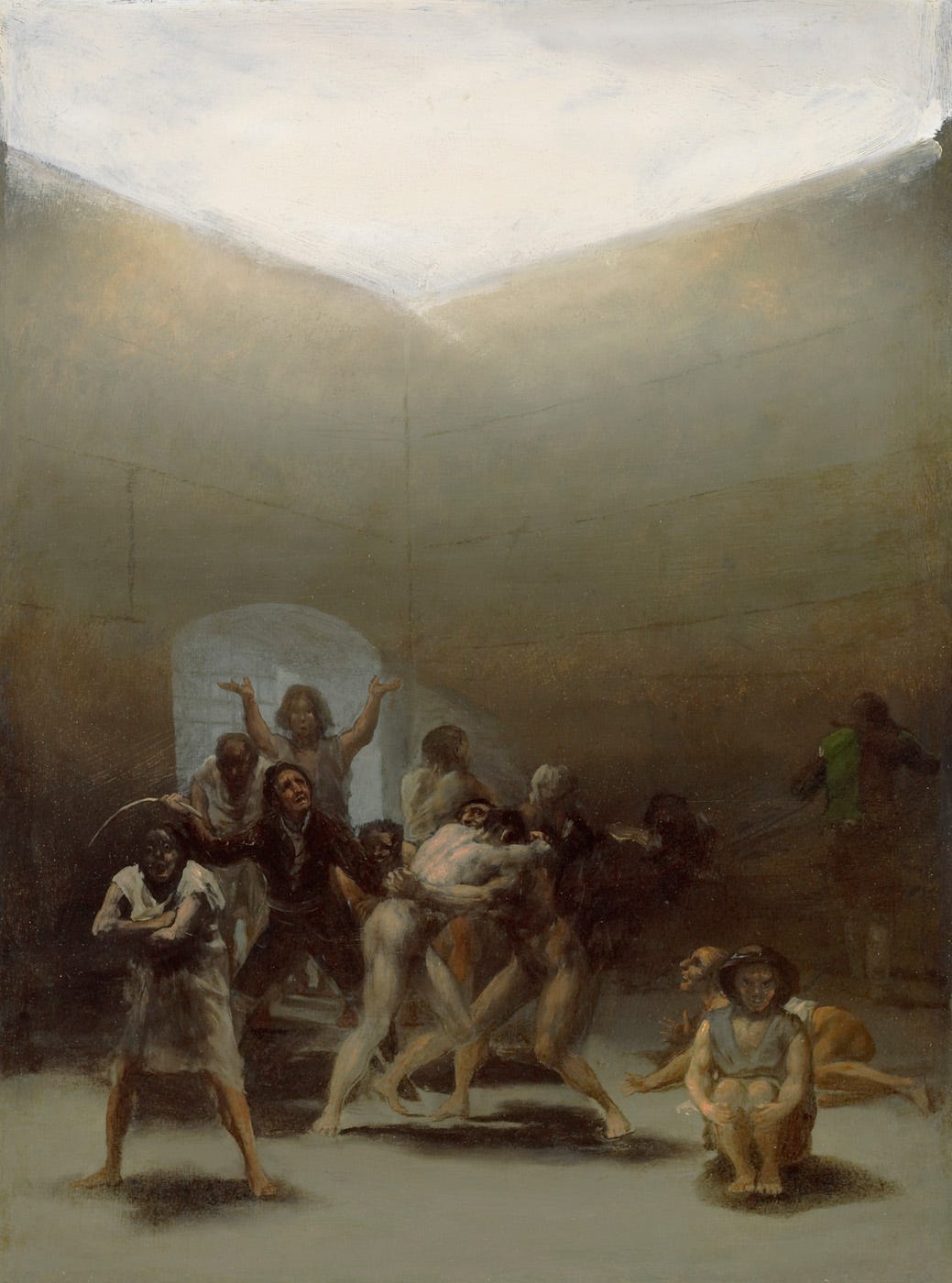

When the time for “applying” came – you never knew when that time might come, but some days you could almost feel it approaching from tension in the air – a code something or other sounded (blue, red, 4, 10 – now I don’t remember what they called it), and my fellow orderlies, also mostly conscientious objectors – Deaconess had a steady stream of us – dropped whatever else they were doing and ran lickety-split from wherever in the hospital they were, to our ward – for a show of force – and when the show proved too feeble to quell the storm, an application of muscle and leather straps. These were not minor tussles. How amazing the strength of one desperate being in the grip of terror and hell – enough, almost, to triumph in the face of half a dozen fit young males, in the grip of terror ourselves. And the screams! Still chilling after 50 years.

And then there was the electro-shock therapy: a shock, even though I wasn’t the one with electrodes attached to my temples. Pills, shock and the occasional lobotomy seemed to be the therapies of choice - maybe the only ones available. I don’t know what else might have been possible then. To this day, I still fight pills myself, every time my doctor offers them; she doesn’t understand why I put up such resistance. Though I suspect sometimes she might like to apply those leather “restraints” – to my mouth!

The shock of the shock the first time, like the thud of the closing door, and the screams that accompanied “applying,” is still vivid for me. I think now, maybe, electro-shock is no longer a therapy of choice. Then it seemed standard, at least at Deaconess, for the severely depressed – often so deep in their own dark nights that they were almost comatose. My part in it was just to be there to make sure the patients didn’t fly out of bed when the current started.

I remember one woman (our depressed patients seemed almost always to be women) who returned time after time. Most times, when she came back to us she seemed hardly there in her body, certainly not in her mind. After a week or two, and a few rounds of shock, she’d leave again, smiling and happy-(seeming). And then, a few weeks later, she’d be back. After her first few visits I’d moved to cookie hours, so I saw her only as her smiling self, if I saw her at all. At the start of each visit, before the “therapy” had worked its (dark) magic, she stayed mostly in her room in bed, and the nurses tended her.

But it’s her unsmiling self I still see in my memory after 50 years, her body convulsing when the doctor pushed the button on the machine, her arms tensed and shaking as that awful sound pierced the room and the current shot through her, her hands, fingers flared like talons. Even to me, who only saw and heard it, it seemed to go on forever, though it was only a few seconds. And then the electricity stopped and her body relaxed. Awful as it seemed, in a few days she’d become herself again, and would go home, and be herself for a while, until she came back again.

Though most days were of the just-another-day sort in which nothing of particular note happened – that I knew about, anyway – still I saw and heard things such as I’d never dreamed of. Some you had to laugh about to keep from crying, or worse, despicable as even the thought of laughing in such circumstances is – I so regret it now. The woman, convinced demons had implanted transmitters in her head, so she wouldn’t speak above a whisper – lest they hear our conversations – about which cookies to bake for after supper, perhaps? The depressive who’d worked for decades putting the bases on light-bulbs in a GE factory – there was no light in her eyes. The lovely, smart young woman who came to my party as a guest one night after her discharge, and whose schizophrenia hadn’t been tamed enough to prepare her for the stuffed alligator my roommate placed at the door to greet all our guests. The woman who tried time-after-time to end it all by slashing her wrists – until her exasperated doctor told her that the effective way of suicide by knife was slashing one’s throat ear-to-ear – and the next time she did.

Even after all these years, the tears flow as I remember them. As I remember, I’m troubled about my part in all that happened. Did I do right or wrong? I do believe that everyone was trying to do right.

After two years, my time in the locked psych ward ended. I turned in my key and another staff member let me out the locked door. I heard it clonk one last time, from the other side. For all that I may have learned from the experience, there’s no way I would have chosen it. I haven’t been back since; I never want to. But in some ways, I don’t have to go back. Some days, in some ways, I still feel as though I’m trapped behind that locked door – without a key – waiting for the straps and shock, and knitting furiously on a garment that will fit ME.

Your story had me back at work doing dementia research. I recall an elderly Jewish lady who in her delusional demented state was thrust back into the concentration camp once more. This was so sad because she was so frightened and no one could console her. This was in about 1991 and I believe that the treatment they finally employed was electroshock which I think did benefit her although I'm sure it took what was left of her cognition. Now I guess they would choose something much more humane like ketamine or psilocybin.

This was quite terrifying and tragic, as was the war you avoided. Thanks for sharing