I think it was her love affair with LOVE that drew me to Wilma first. Love that did her wrong more times than would seem her rightful share. Love that she looked for in wrong places; that she gave herself to too fully and often; that never could, in this world, reach the heights that she hoped for from it.

You will not have heard of her. Almost certainly not. And there’s no reason why you should have. She was a poet, but a minor one, as they say – almost miniscule in the pantheon of poets. I hadn’t heard of her either, though now that I have, I find I can’t forget her.

She’s no relation of mine, or anyone else alive today that I know of. Not directly, anyway, since she had no children – though there may be nieces, nephews, cousins – or by now it may be that there may have been. Who knows? I don’t.

I found her myself by accident, while looking for someone else.

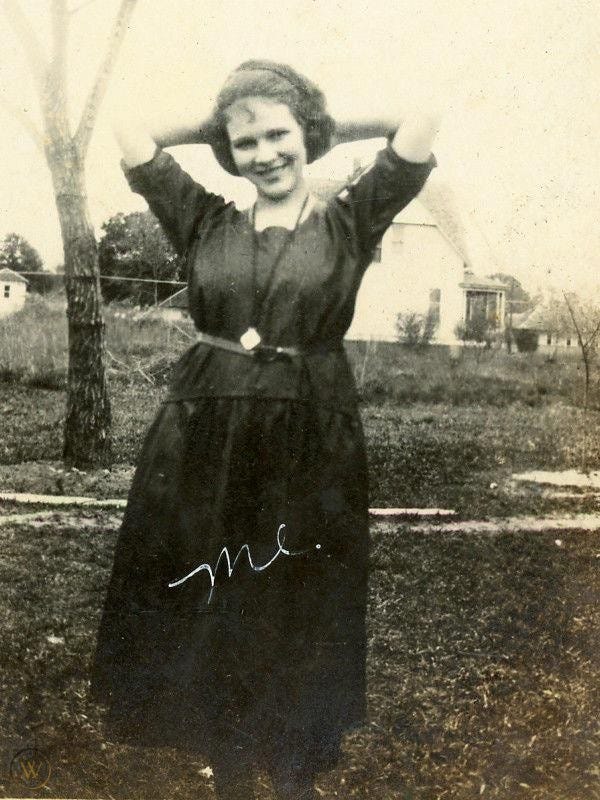

Born Wilma Ethel Crittenden, in Mississippi, in 1903, she grew up in Houston, went to Houston Heights High School, from which she graduated in 1921 – graduated full of romance and poetry, perhaps instilled in her by some now unnamed English teacher – a spinster, perhaps (to use a now scorned term, common then), herself full of romance and poetry?

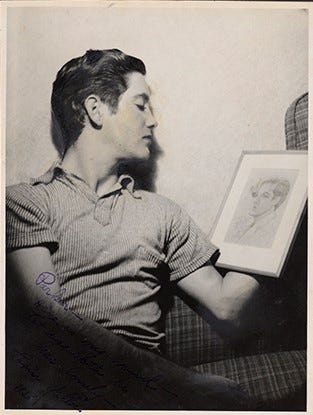

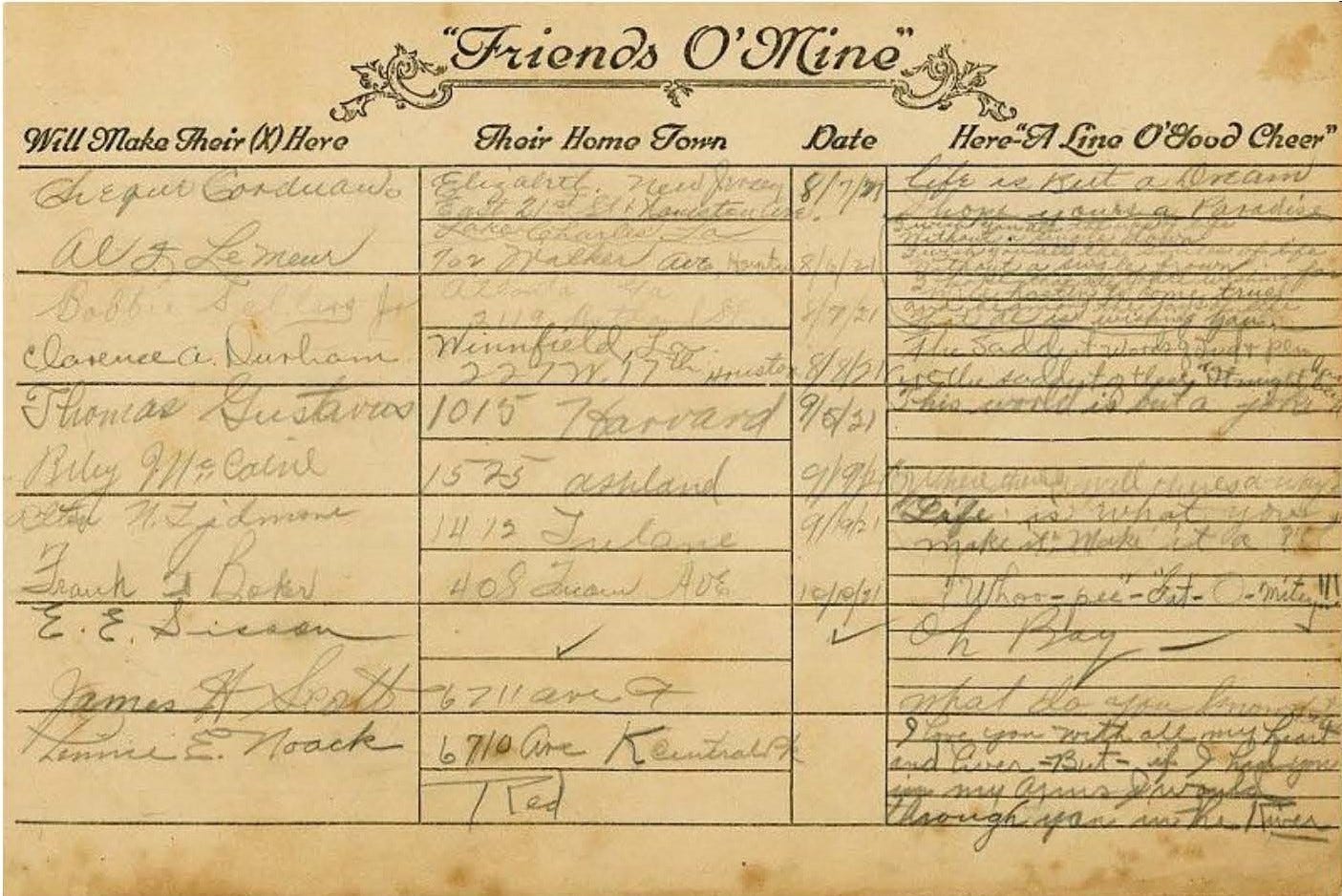

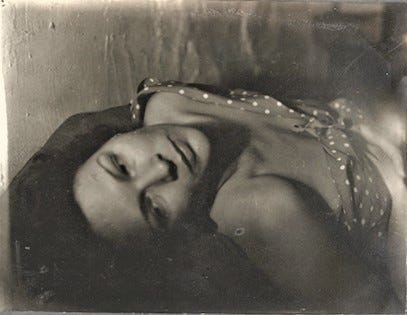

From that time, Wilma left behind a now lost album of memories, loves, hundreds of photos – all but three now gone – and pages titled “Friends O’Mine,” inscribed with names (all BOYS!) and wisdom: “Life is what you make it. Make it a ?”

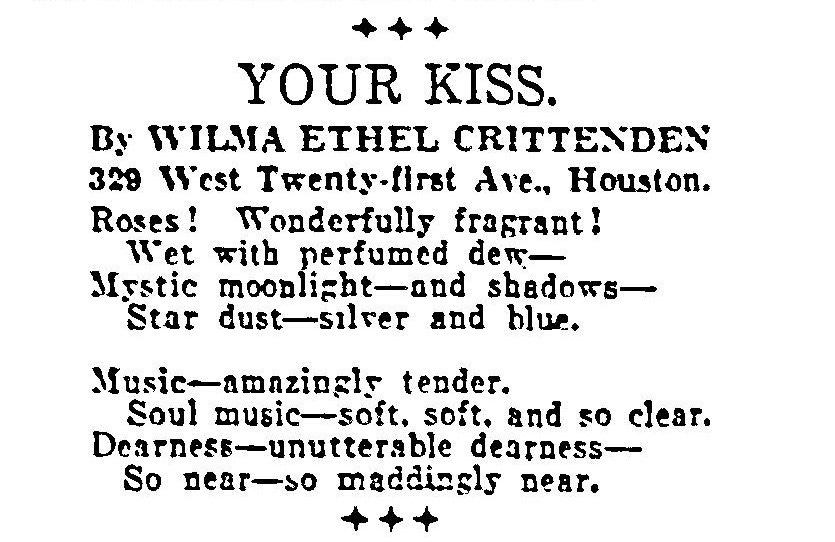

Though later on she seems to have set herself the goal of turning the question mark (?) into an exclamation point (!), she started her search, like many young women of her day, doing “women’s work”: for her, stenography. A car accident in 1923 almost killed her – one Houston paper said it had – but that was wrong. She lived. And so did her romantic soul, which she turned into poems. The first published one that I know of, “Your Kiss,” appeared in the Houston Post in 1925:

Lines that did not bode well for an easy life of the heart. And so it’s no surprise, perhaps, that the titles of her next published poems were: “Waiting” “Wondering” “Longing” “Heartstorm” – followed in a year or two by “Tears” “Fantasy” “Futility” “Forsaken.”

“I should not care that you are gone/I should not – but I do,” she said in one. Then in another:

And those soft breezes

Turned to bitter cold

Chilling the very heart of me.

Dreams are like that.

She gathered her poems together and saw them published as Paths of the Winds (Galveston: Mueller Print Co., 1930). Only one copy seems now to exist, inscribed to Stanley Babb, Literary Editor of the Galveston News. We can hope that he wrote a review. Though I haven’t found one.

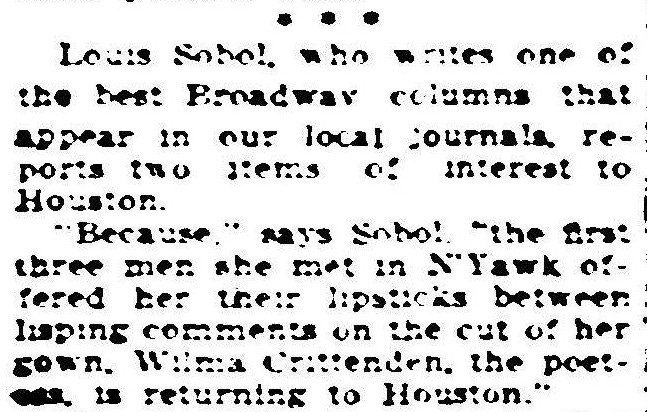

By the end of the 1920s, Houston had become too small for Wilma; she left for New York. And, oh, the crowd she found there! She even made the gossip column back home once, in the words of Broadway columnist, Louis Sobol:

“Because the first three men she met in N’Yawk offered her their lipsticks between lisping comments on the cut of her gown, Wilma Crittenden, the poetess, is returning to Houston.”

Indeed Wilma did return to Houston years later, but lipsticks and lisps were not the reason why.

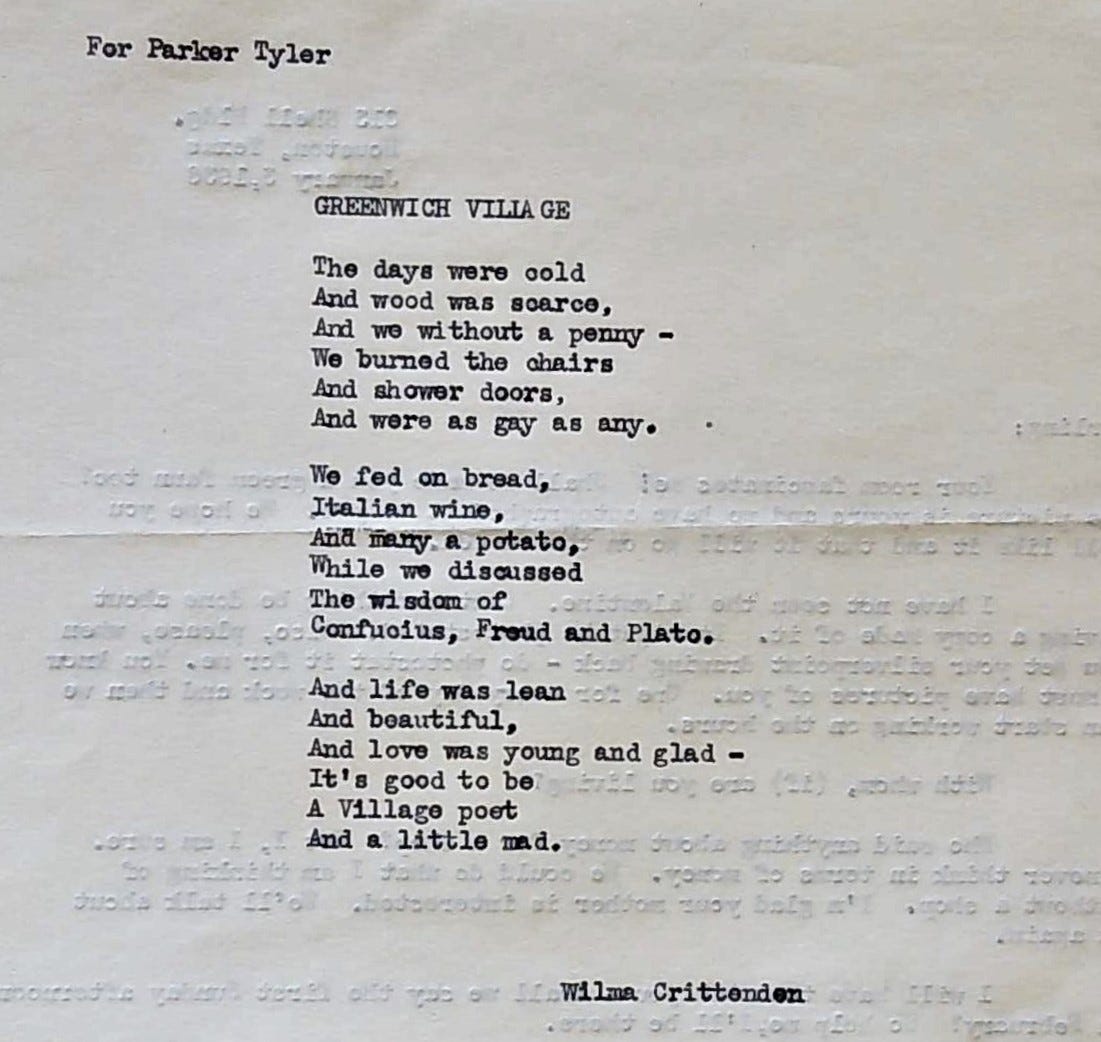

It was in N’Yawk that I found her, while researching her fellow Southern transplant, Parker Tyler, originally from New Orleans, half of the notorious duo (along with Charles Henri Ford, himself from Mississippi, and, briefly, San Antonio) who together wrote the scandalous novel of queer life in Greenwich Village, The Young and Evil – so scandalous it couldn’t even be published in America, first seeing print in Paris, where such scandals had by then become possible. This was Wilma’s New York world, young and brazen and full of hopes/dreams/plans. Hard at times, but a world she loved.

Looking back at those days in a later letter to Tyler, written in 1938, when she’d returned to Houston for a while, Wilma rhapsodized:

To the ongoing ache of her much pained heart, she seems to have fallen in love with the homosexual Tyler, whose own heart she found “unreachable” – not the first romantic, poetic young woman to risk her heart on the unattainable – nor the last.

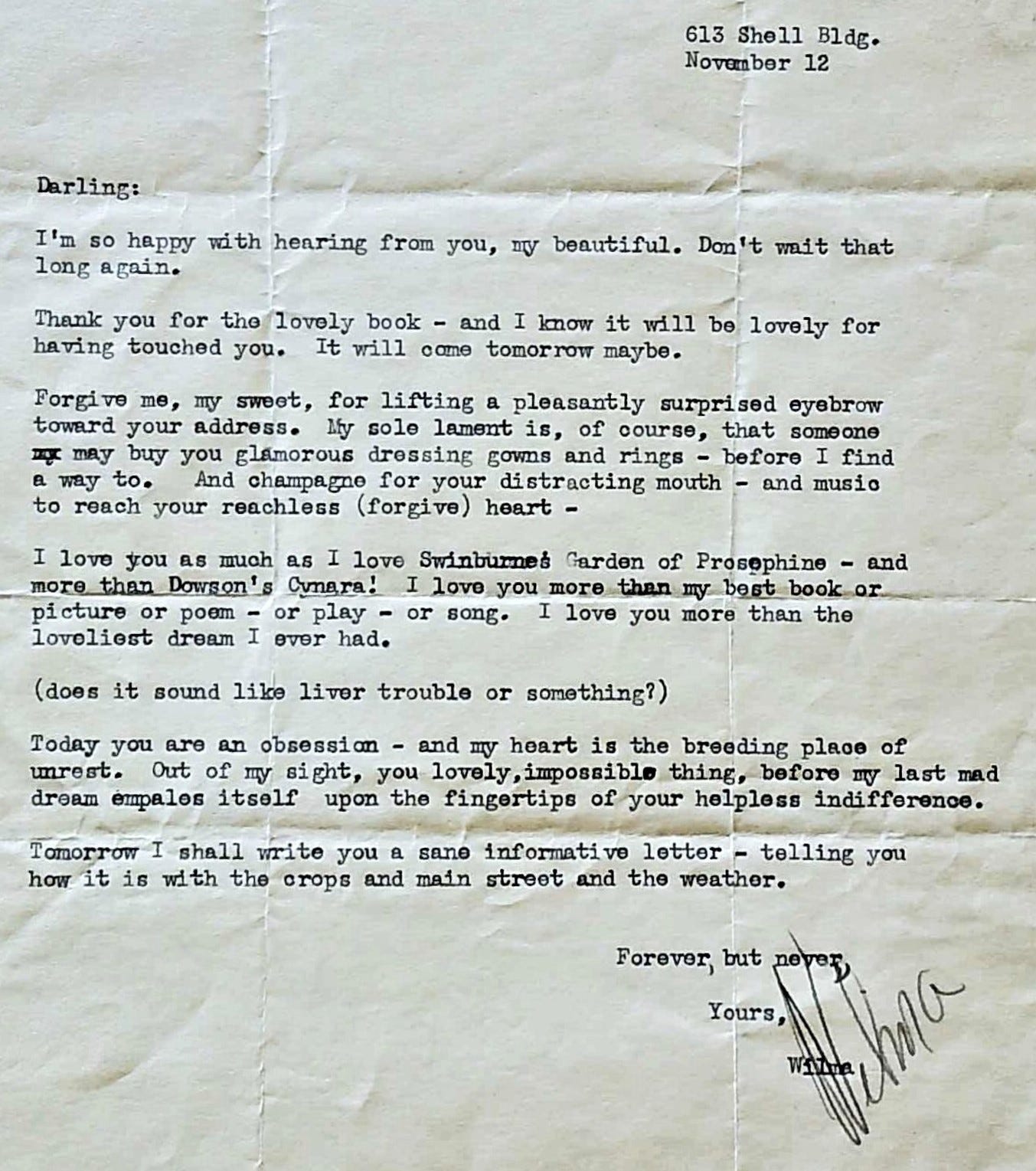

One lonely evening in Houston, she wrote him, after perhaps too many glasses of “champagne for your distracting mouth. And music to reach your reachless (forgive) heart – ”:

“Darling, I’m so happy with hearing from you, my beautiful. Don’t wait that long again. … I love you more than the loveliest dream I ever had. (does it sound like liver trouble or something?) … Today you are an obsession – and my heart is a breeding place of unrest. Out of my sight, you lovely, impossible, thing, before my last mad dream empales itself upon the fingertips of your helpless indifference. Tomorrow I shall write you a sane informative letter – telling you how it is with the crops and main street and the weather.”

And even he was not the last of her unattainable loves.

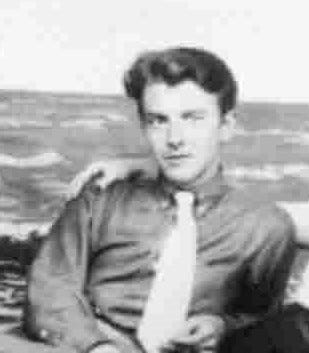

In another letter to Parker she mentioned another she admired (to see if she could make Tyler jealous, perhaps?), the young Houston portrait painter, Carden Bailey, “who is a dream walking,” as she wrote – and who was, at the time, partner of the young Houston painter, Gene Charlton. Ah, Wilma, will your heart never learn?

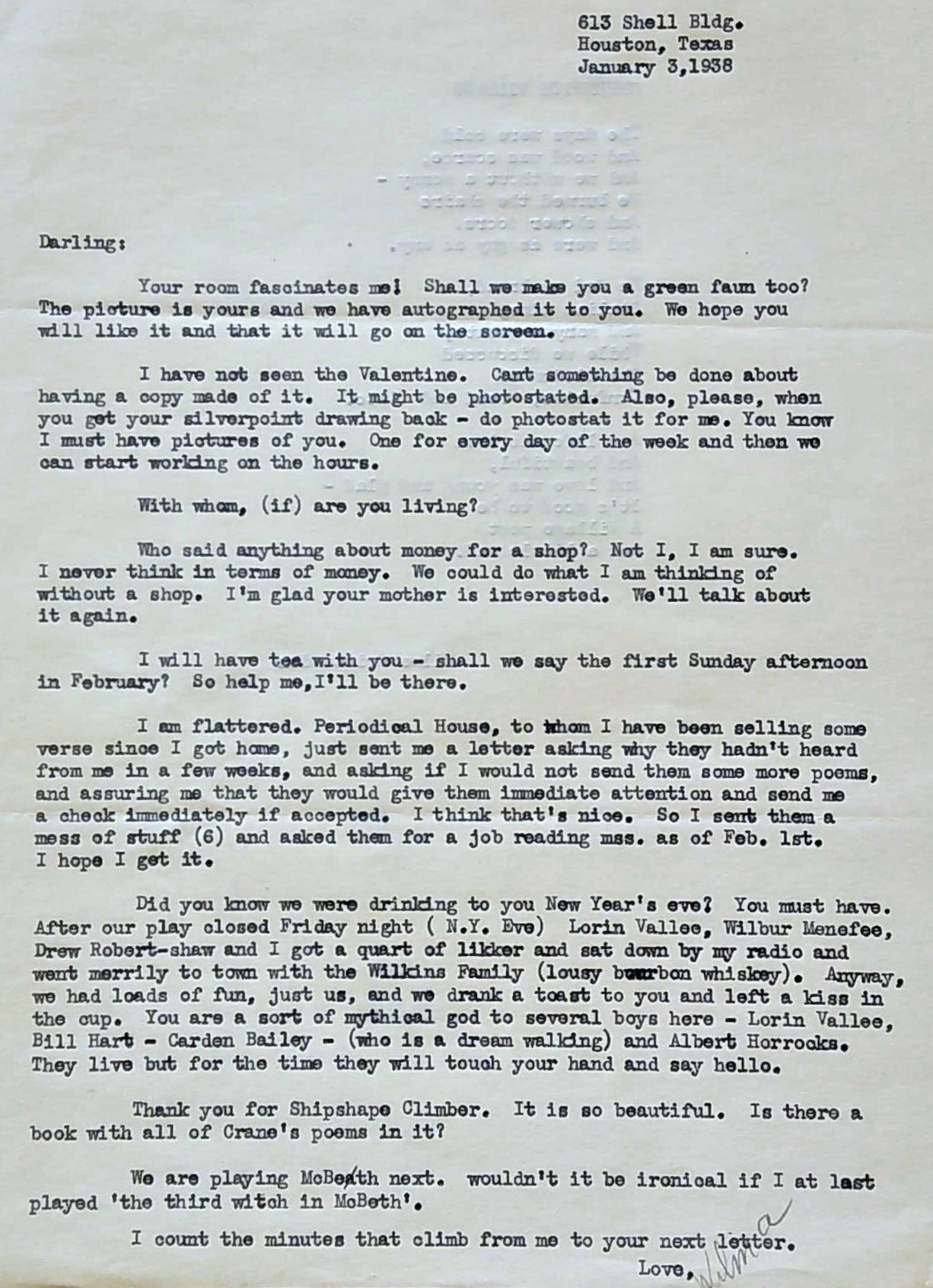

In that same letter, on a more broadly relevant note, if not more serious (what could be more serious than affairs of the heart, particularly for Wilma?), she writes a fascinating, and oh so rare, picture of a “bohemian” Houston gathering, not unlike those she and Tyler had known together, in The Village:

“Did you know we were drinking to you New Year’s Eve? You must have. After our play closed Friday night (N.Y. Eve) … [we] got a quart of likker … and we drank a toast to you and left a kiss in the cup. You are a sort of mythical god to several boys here [in Houston] … They live but for the time they will touch your hand and say hello.”

Documents such as this are so rare in the realm of Queer History that they’re more precious than gold.

All the champagne and likker – and heart ache – took their toll from Wilma. In another, later poem she wrote about it:

Hang-Over

Morning is a dingy room,

cluttered with empty bottles

and sticky gin-scented

glasses…

A sickly sun slinks in,

revealing the soiled linens

and disorder there…

If this is morning,

Must morning be?

Oh, Christ for the plains

and the lost, lost sea!

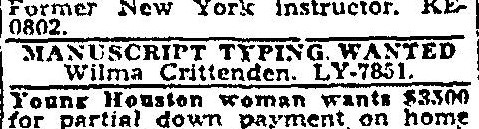

But before we grow too sad for Wilma, we should remember that she did find her attainable soulmate later on – and love, we’ll hope, though she seems to have left no poems or letters explicitly saying so. She and her Marlow [Dawson] married, anyway, and were together until her early end, collaborating on plays and songs by night, from their Houston home, as he worked in the wholesale department of Carnation Co. by day and she typed other people’s manuscripts.

We have to hope she still wrote poems of her own, though none now are known.

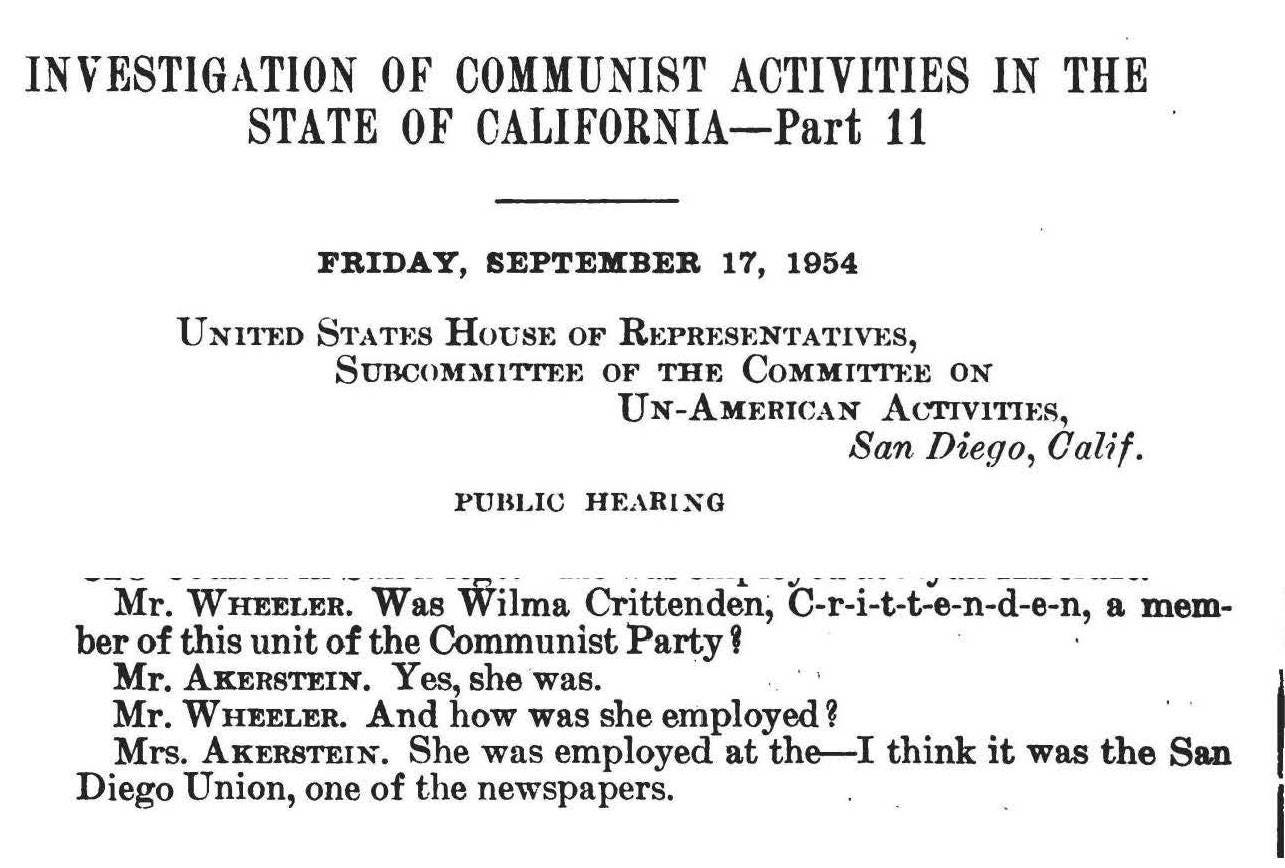

There was an encounter with HUAAC, the House Un-American Activities Committee. For sure we’d be interested in knowing more about that:

And she continued to nourish that love for Parker – as she let him know in her last known letter to him, written in 1953:

“…I might have been harder to dissuade in the old days, had you cut such a broad- chested figure! The only thing that seems to be changeless is that inimitable mouth, quietly smiling, and those unfathomable eyes, not quite hiding the forever dream there. My Parker!”

Like all of us, she was a person of dreams, loves and aspirations: she was “ME,” as she inscribed on her girlish photo. And like most of us, life and love perhaps let her down – or at least they didn’t take her to the unattainable (as it turned out) heights she’d hoped for. WE can hope they took her high enough, at least, so that the satisfactions outweighed the disappointments. What more can any of us hope for – once we’ve made a truce with what’s unattainable?

That’s as much as I know about Wilma. As I said before, now that I know her, I can’t forget her. What a tribute it will be if, now that you’ve met her, though only briefly, you once in a while remember Wilma too.

I'll never forget Wilma!