Being found proved to be a bittersweet blessing, especially since, until the finding, I had no idea that I was lost.

It came as a bolt from the blue when my mother called one day, hysterical, babbling about my father’s daughter. Which made no sense. My father didn’t have a daughter. He had two sons: me and the brother I’d never met, from a failed early marriage. I knew his name; I’d even seen photos. The bitterness of desertion (I supposed) meant that he had no ties with our shared father, or with me, aside from blood, which, no matter how thick it’s said to be, was too thin to bind us together. But no daughter, so what could my mother be going on about?

My parents had been married for 40 years when my father died. By the day she made the incomprehensible call, Mother had been a widow for half a decade, living on her own, in the house I grew up in, 500 miles away. I was the only child of my parents together, though she had a son from a previous marriage. As her principal family helper, I made frequent visits to do what I could to help her life run smoothly, as smoothly as could be with the onset of age and ailments. I’d just been there days before; all had seemed usual then. Clearly something had changed.

Between tears and hysterics, she stammered out news of a letter from the “government,” a daughter looking for her father, a request for permission to share contact information. I already knew that my father had a past – a long-ago life of failings and flaws that he’d tried to leave behind when the US Army brought him, during World War II, from the Down East of Maine to the Way Out West of Texas. There he wooed and wed my mother, a 30-something widow with a teenaged son, and they set into their second-act lives together in the Texas Panhandle – a locale perhaps particularly appealing to him since it seemed so very far away from his past.

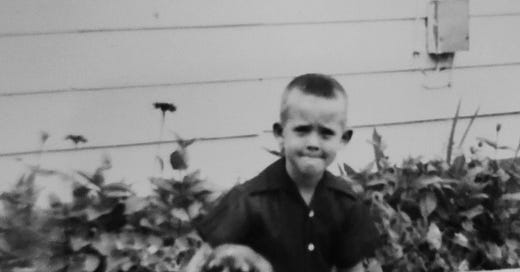

Parents, who in real life are just people like the rest of us, are never perfect. They have their flaws, as we do – and their virtues, though the flaws are so much easier to dwell on – and so tempting as excuses for our own. Certainly my father had his, most blatantly manifest for his young son – me – by way of drinking. His alcoholism was a fearsome terror through my years with him – and, sadly, a legacy bequeathed to me as well.

I have difficulty remembering much about him that doesn’t include drinking and trauma. We shared little, aside from blood and my mother/his wife. He was the absent father, even while living in the same house, and for him, I must have been the absent son too – the second absent son – growing more adept year-by-year at hiding the most fundamental me, the gay me. I had no inkling of his inner life, nor he of mine. I don’t remember a single conversation between us about anything important – or even anything trivial. He stopped drinking later, and life was better between my parents, but I was already grown and gone by then, the habit of distance long established for me and for him.

So learning, from a mother in hysterics, years after his death, that he’d also bequeathed me an unsuspected sister, when I thought I’d dealt with all he’d left behind, came as an unnerving shock. Selfishly, at first I thought only of how it burdened me – no understanding, or even sympathy, for his demons, some of them my demons too; for my mother’s shock, which must have been so much more profound than mine; or for my new-found (or new-finding) sister’s longing to discover her own blood.

After a while – after an emergency flight to calm my mother – and after a tearful explanation of a courtship before a divorce, and a birth before a legal marriage, and the implications for me, and for my possible moral judgement of her – though she’d only discovered it all herself long after, she said, and I believed her, of course – we approached the other issue: how to respond to the contact request, coming through the US Military Records Office.

My mother knew about my father’s (her husband’s) other son, but she had no hint that he had a daughter too, by yet another wife – she said, and I believed her. At her age, and in her state of mind, she also had no interest in knowing more, or at least dreaded the prospect. And since such a daughter was not blood of hers, I saw no justification in forcing her to.

But if what the letter said was true, she – this stranger from a distant father’s past – was blood of mine, which should (so many seem to think it does) mean something. I decided to explore further, cautiously. Even an unintentional mistake would have major consequences.

Much has been written about the rights and desires of those searching for their biological connections, unknown due to adoption or anonymous donor conception or other separating circumstances. We appreciate their longings and admire their quests. Finding those lost connections can have practical, as well as unpredictable intangible, impacts in their lives.

Not so much has been written about those on the other side of the finding: those found – though the impacts in their (shall I say, OUR?) lives can be staggering too – and even more an earthquake, without the years of searching and anticipation.

I sent a letter to the address given. A reply came almost instantly. She was overjoyed at finding us at last – disappointed that our father was dead – she had so wanted to know him, for him to know her, to share the love of father and daughter they’d been cheated of. She acknowledged a stepfather who tried. But a stepfather could never replace a real one, for her, at least – not the real one she’d idolized (idealized) through years of searching. But even though he was gone, a new-found, unsuspected brother might do.

We exchanged more letters, and family photographs; we talked on the phone; I went to visit. She had a husband, sons, grandchildren; I had a partner (who could not legally become my husband for 20 more years). We shared understandable, though still unnerving, similarities of person, personality, propensity – the foundation elements. And yet there were dissonances too, not least, her eagerness and my wariness as we began our relationship. But we both tried – in the early years.

I know I disappointed her in many ways, some big, some small. I sensed her disappointment when she realized that I was only a librarian at the university where I worked, not a professor – or was that projection; who knows? I disappointed her by disagreement when she said she knew my mother must have known about her all along – and so, called my mother a liar without saying the word. I disappointed her, almost cruelly, during an early meeting when I couldn’t (or wouldn’t) bring myself to validate the fantasy father she described – the one who’d left her without a thought, who’d never made the effort to find her – though she knew he wanted to. Instead, I described nights of childhood terror, shivering outside in the dark, for fear that the real-life father – the one she’d never known – in his drunken rages, might find me out there too. Why did I do that to her? He was long dead – what good could “real life” do then? I longed myself to know the father she described. Perhaps I resented that she had her golden fantasies to live with, while I had my dark memories. And so I was cruel. I regret it now.

I suppose I disappointed her most of all by not opening my arms in joy and welcoming her unreservedly as family. That would have been the natural thing, so people say. Because blood is thick, and family is what matters in the end. And she had a right. She almost said as much in a later letter, as her disappointment grew – a letter that read almost as a threat, an imputation of guilt.

In real life, siblings, even long lost ones now found, are just people like the rest of us. We have our faults – overeager expectations, based on years of fantasies; wariness and obfuscation, based on lifetimes of hiding and hurt, among them. Our shared father used to say, with melancholic delight (or resignation?), “In a hundred years we’ll all be dead, and no one will care anyway.” Oh, what a joker he was: it won’t be anywhere near a hundred now. But that would be too bleak a note to end on.

It’s more than 30 years now since the “finding,” and, unlike the fairy-tale endings that make the news, my sister and I have grown old apart, as we were young apart. I’m sure I’m the loser in this being apart as much as she. We’ve exchanged cards for birthdays, but little else for years. This year, her card didn’t come. I don’t know why, but at our ages, the possibilities are mostly grim.

I’d like to blame our faults on the man who was the absent father of three children – four, if you add his stepson in. But that would be too easy and pass-the-buck. And anyway, blame isn’t the point. The point is … Well, I’m not sure what. The fact is, we each have our part; our lives are unmanageable, no matter how hard we try; and we may find that, for whatever reasons, even blood isn’t thick enough in the end, no matter how fervently we’d like for it to be.

So touching and yet right to the gut.

The ping of pain stays.

A thoughtful and relatable story of family and all the complications of family.