Not Just Another Cheesy Story About Gay Guys and Sex

A Saint Louis Story of the 1970s

(NOTE: To answer upfront the question already asked by my Proofreader/Husband, No, this is NOT autobiography, it’s fiction. But then aren’t all stories?)

This is not going to be just another cheesy story about gay guys and sex. This is a story about two gay guys (young and randy, so, yes, there was sex, but sex wasn’t all) who didn’t quite manage to keep their love alive. Or, more precisely, about one guy, who desperately wanted to, but floundered and failed. It’s not something you can manage alone.

Raindrops pelted the gutter outside the kitchen window in not quite individual thuds. It was a cold winter rain that would turn the streets to sheets of ice by morning. Already, I heard the whir of spinning tires. The sound of rain hitting the gutter would keep me awake all night now that I’d noticed it.

I took a Valium out of the bottle I always carried in my pocket and wiped away the gilding of yellow dust gathered on it. I swallowed it and lit another cigarette, clinging to the dubious comfort of drug-promised placidity on the way.

I looked at the clock on the kitchen wall and wondered how late he’d stay out tonight – or if he’d come home at all. Sometimes lately he hadn’t. I knew from experience how much of the charm goes out of making two cups of morning coffee when you have to drink both yourself.

We’d been together almost three years. It would be three years in a month and six days, and we’d have an anniversary celebration and exchange of gifts – if we were still together. I tried not to think of the possibility we wouldn’t be.

The night we met had been much like this one, cold and wet. I didn’t remember many of the details: which bar, what song, how we’d got to where we spent the night. Drinks and drugs made sure I wouldn’t. But I remembered the next morning: the first chill hints of approaching winter in the air; a lace of frost glistening on the window beside the bed; waking up next to a beautiful man. Even though I only vaguely recognized him in the dim morning light, waking up beside him warmed my spirit. I reached out and ran a hand down the smooth chest and stomach. He opened his eyes and looked over at me. I pulled him close and we kissed. We had sex again in a lingering half-haze of sleep and alcohol.

Over coffee (and after Valium) we re-introduced ourselves: “I think I remember your name,” he said, “but why don’t you tell me again to be sure.”

That first day, we spent mostly in bed, a mixture of passion and hangover. By evening we’d recovered sufficiently to stay in bed solely for passion. Neither of us had to ask if we’d spend the next night together, or the next. By the end of a week, we took it for granted that we were an “item.” “Couple” sounded too old fashioned for gay men of 20 something in the 1970s.

I took a long, deep drag on my cigarette and blew it out slowly. I sat with my eyes closed trying to feel some pleasure, or at least some comfort, from the smoking. I heard the scratch of a key in a lock and looked up. For a moment my body went taut. Then I knew it was someone else’s key in someone else’s lock – keys and locks that had nothing to do with me – and I went slack again.

When I first sensed that something might be going wrong between us, I started preparing myself, squirreling away remembered perfect bits of our time together, which I could dig out of memory to get me through, if I needed them. At least bits I remembered as perfect.

I remembered sitting next to him in bed the first Sunday morning, the New York Times scattered in sections over the bed and floor. We drank strong, black coffee, made inconsequential conversation, shared deep kisses at frequent intervals. The realities of stubble and disheveled hair – shamelessly ignored in the movies – only made the intimacy more comforting.

I remembered our first vacation together, in Key West: lying awake the last night, feeling the dry burning from beneath my skin which meant the burn had gone deep and I’d be on fire tomorrow. The air smelled of salt and sea. In the stillness, I almost heard the conversation of a couple passing in the street below, their words drifting through the open window on the humid air. I felt the late-night intimacy of a side street in an old tropical town. I looked at him lying beside me asleep, his chest rising and falling evenly, the sheet, pulled half-way up his stomach, outlining his legs. I fell asleep myself thinking discredited words like love, joy, contentment.

Since then, there had been many nights, now all blurred into one, when I’d lain in bed aching for a hint that affection still existed between us. I’d lain very still, keeping precisely to my half of the bed, wide awake no matter how exhausted, hoping that, if only for a moment, if only by accident, he would reach over and touch me. I’d willed it so strongly that my muscles had ached and my head had throbbed. Finally, when I could stay still no longer, I’d reached across to him. And when there was no response – and for months now there’d been none – I’d felt alone, little, afraid of a darkness that might go on forever. If I was drunk – and now I was often drunk – I would get out of bed and go into another room to lie alone and tremble until Valium and alcohol drugged me into a semblance of sleep.

But still, I couldn’t face the possibility of life without him. I’d tried a hundred (or was it a thousand?) times to understand what was going wrong. Each time, I started at some plausible beginning of an end, thought through a string of events which might explain it, came to the same inexorable point of incomprehension. In my heart I knew there was only one conclusion which made sense: that there was just nothing left between us, that it was time to end it. That explained everything – and I refused to accept it.

I lit another cigarette and twisted the empty matchbook into a knot. I took a deep, disappointing drag and blew the smoke up toward the ceiling.

I’d come home that evening to a tangle of coat hangers on the bedroom floor and random empty spaces in the bathroom cabinet. I knew I should let those signals tell me something. Of course I knew it. I wasn’t stupid. But, of course, I wouldn’t. After all, he’d done foolish, dramatic things before, his drama one of his most alluring traits. That was part of what made us a couple (“couple,” after a year or two, had no longer seemed so old-fashioned). He was the dramatic one, I the steady one. Everybody has a role to play, and I lived for mine.

I stood up and walked into the bedroom. Maybe if I went to bed, I’d go to sleep, and when I woke up he’d be home.

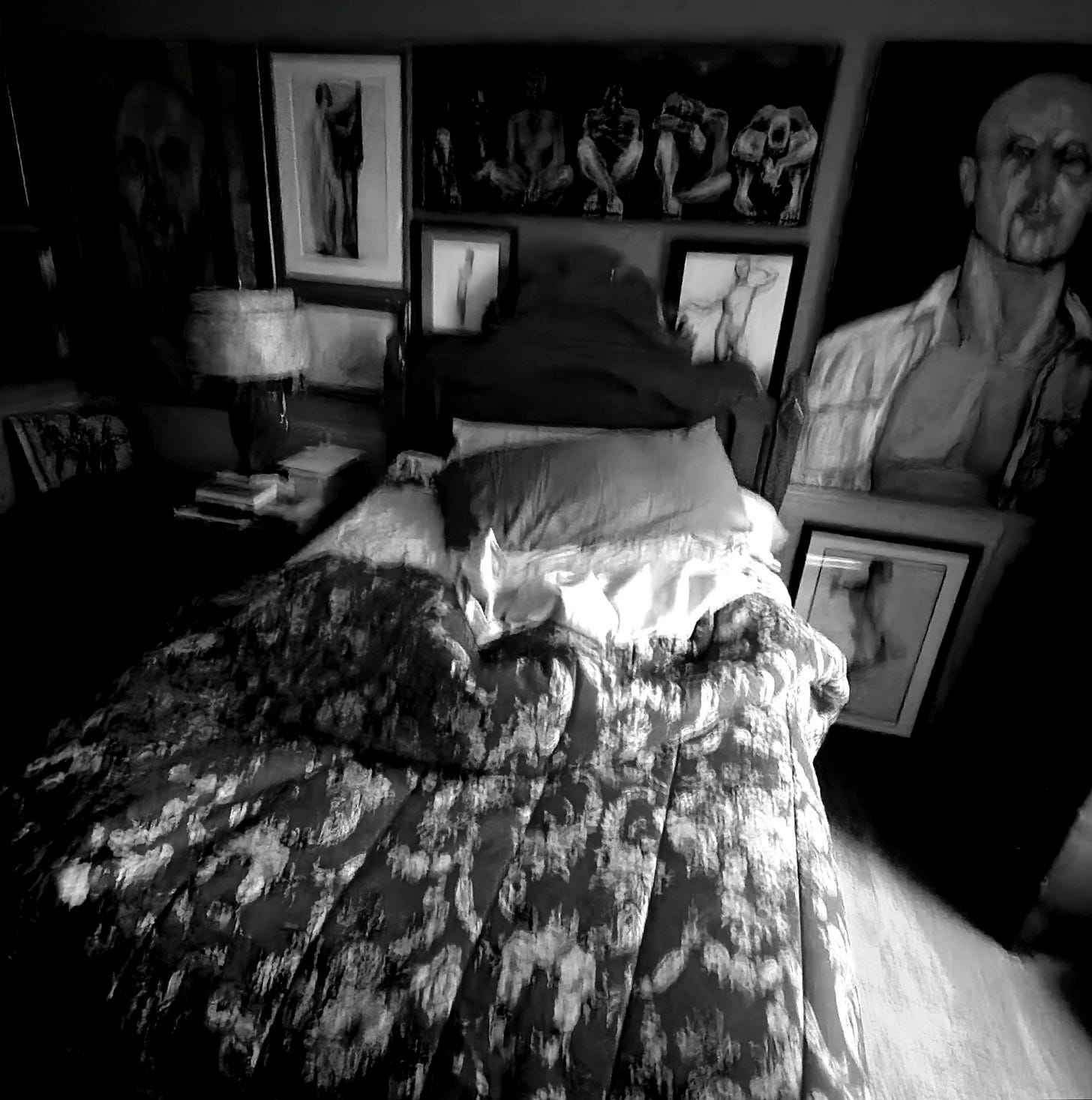

I sat down on the bed, unmade from the night before and the one before that. I switched on the bedside light. A dozen half-finished novels lay in piles at my feet. I could still hear the rain hitting the gutter, the sound softer in the bedroom, almost comforting. I took another drag on my cigarette and stubbed it out in the crowded ashtray on the bedside table. I bit my lower lip and narrowed my eyes in concentration.

If I could think back day-by-day, maybe I could remember the day when things had begun going bad. There must have been a day, a minute, when we’d turned the wrong direction. I tried to remember the day when showering together had lost its charm, when sleeping two in a single bed had become definitely out of the question. In the early days, none of the inconveniences had mattered, as long as we were together. We could lie in each other’s arms forever after sex, never mind the earthy aftermath realities. Now, had there been sex at all, it would have ended the instant after the ending. But now there never was sex, and everything seemed inconvenient. To him, anyway.

I thought I knew him. Almost three years together had led me to think so. I knew his likes and dislikes; I knew his habits. I knew that he always gave a short, breathless little laugh at the end of orgasm; that he sniffed the armpits of his shirts to see if they could be worn again; that he washed out plastic bags so they could be reused. I knew all the insignificant things that make a person – that made him. But at the same time, I seemed not to know him at all.

Were we different people from the lovers I longingly remembered? We must have been. Nothing else could explain such changes. But how did we get to be so different without noticing, without wanting to? The changes had crept in so gradually I couldn’t remember the beginning of any of them.

Maybe he knew from the start that sooner or later there would be bad times and an end. When we moved in together, he’d insisted that we mark our underwear and socks (so that ownership wouldn’t be in question at the end?) A little thing at the time, now so prophetic.

What would my life be if he didn’t come back? My mind could hardly make meaning out of the words – as though they were sounds from a language I neither spoke nor understood. I closed my eyes and winced from the pain which pierced through me with the question.

But, of course he’d come back. There was no question of that. Love – true love – lasts. Love like the love we had.

I’d always dreamed of a lover – a beautiful, strong man whose spirit would mesh in some mysterious way with my own. A man I could respect and admire; a man I could love and who would love me. From the very earliest days I could remember, I’d measured every man I met against my dream, and, every one, somehow, sooner or later, had fallen short. Until I met him. He had measured up in every way to every dream. I’d found plenty of men to fill the cravings of my body; only he had filled the cravings of my soul.

And now he was threatening to leave – perhaps had already left. What would be left behind for me if he did, besides the tangle of hangers and empty spaces? Would there be anything left worth waking up for in the morning? Would there be anything at all?

I lay down on the bed as the Valium kicked in. I felt the synthetic warmth flow from my head through the whole length of my body. I closed my eyes, and listened to the faint thuds of raindrops pecking the bedroom window. They no longer sounded cold. My cigarette burned itself out in the ashtray, the filter at last falling from its own weight onto the bedside stand, and the frail finger of ash crumbling into a powder. I ran my hand down my chest and stomach and smiled faintly as I thought of him pressing against me, taking me out of myself into a safer place of warmth and tranquility. I fell asleep knowing that I had nothing to fear. In the morning, when I opened my eyes, he’d be there, filling me with his body and his being. Yes – he would – for sure.

OK, I could have handled this on a sunny winter day but it's hard on such a gray one. I've certainly been there waiting for an errant lover to come home. Alas, having the lowered libido of a 70 year old woman makes the craving less but not the longing or loneliness.

This is so sad. You are so fortunate to have your “editor “ now