Mrs. Cherry's Modernist Group

A Very Modern Houston Painter in the Early 20th Century

(Note: You can find more posts about Houston Art History under the section with that heading.)

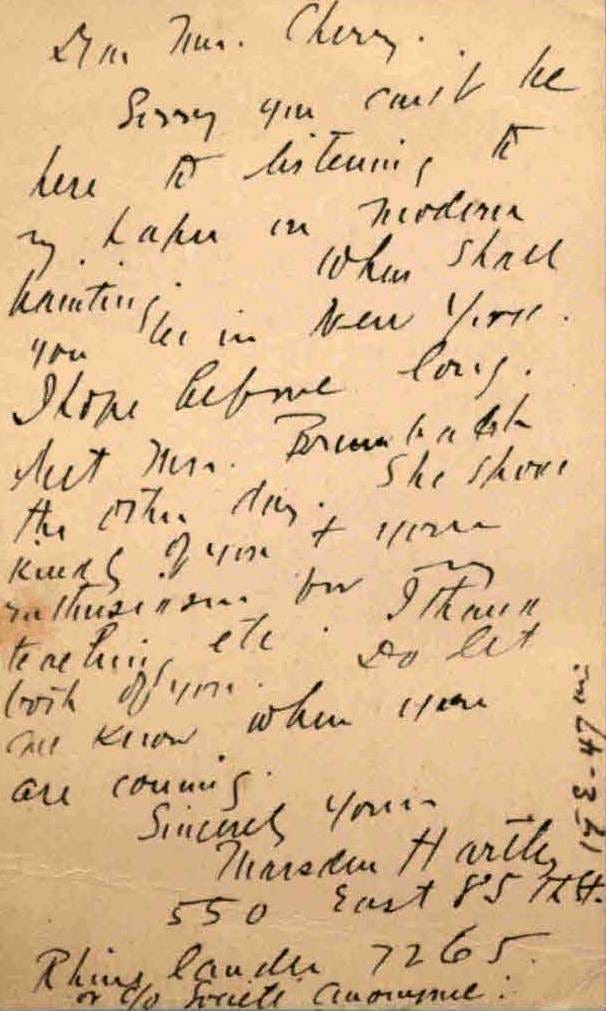

“I wanted more modern help,” wrote Emma Richardson Cherry (1859-1954) from Gloucester, Massachusetts, in September, 1920. “So the other day I asked Mr. [Marsden] Hartley if he would come & look at my summer’s work & see if he thought I had any inclinations that suggested I could break loose and really do modern stuff.”

“Well he came & was quite interested … said ‘well, if you can draw like that you can go any length you wish.’ You can imagine I was pretty happy.”

Turning to a canvas-in-progress that she had just brought into the studio from an en-plein-air painting excursion – and with her enthusiastic permission – Hartley even “started in on my wet paint & I can tell you it’s far & away a mighty interesting thing he is doing, with my puddling around in it, pretending to help.” (For a full transcription of the letter see the HETAG Newsletter for June 2017.)

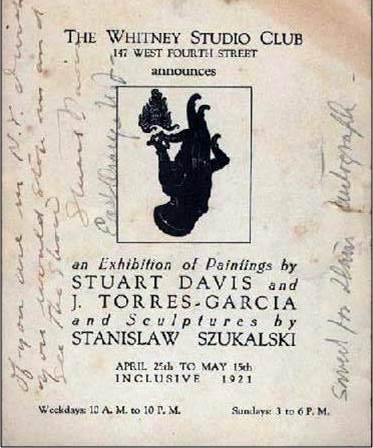

Modernism was in the air among serious American artists by 1920, and Marsden Hartley, who as Cherry noted, “paints very modern pictures,” was one of its foremost practitioners. She could hardly have picked a better instructor in the Modern – though she did also make the acquaintance of a young Stuart Davis on the same Gloucester visit.

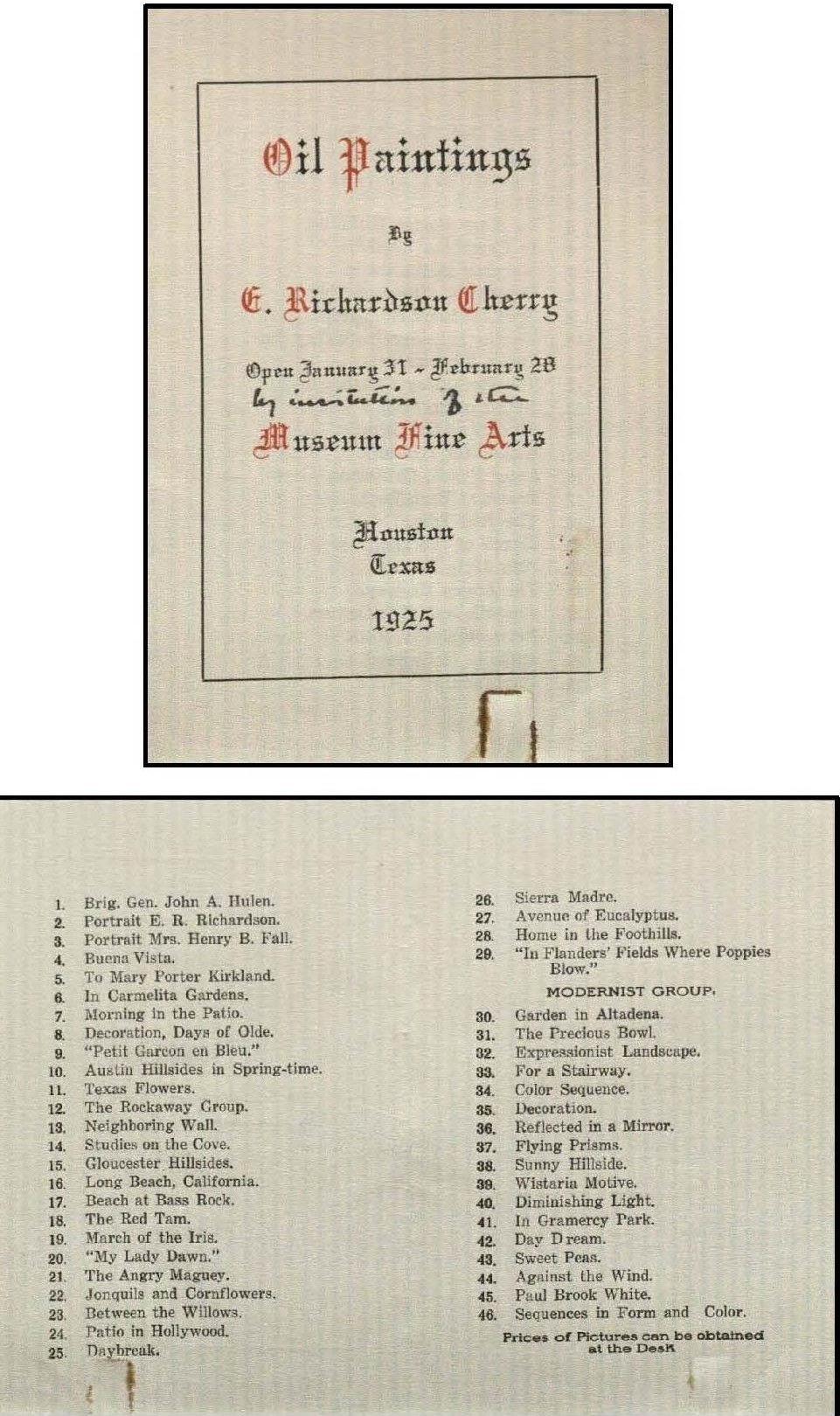

Over the next five years she consciously reshaped herself into a Modern painter. Though she continued to paint portraits and the more traditional flowers and landscapes for which there were paying customers in Houston, at the same time she explored the tenets of Modernism and employed them to create a group of paintings which she defined as “Modernist.”

By 1925, Cherry had enough such works that she gathered them together as a “Modernist Group” for her one-woman exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston in January. In April, when the show traveled to Denver, where Cherry had lived in the early 1890’s and where she still had strong ties, her “Modernist Group” was still a separate grouping. And so it was as well in December, 1926, when a major exhibition of her work opened at the Witte Museum in San Antonio, though for that show she added some works done during her intervening months of study in Europe from June, 1925, to October, 1926.

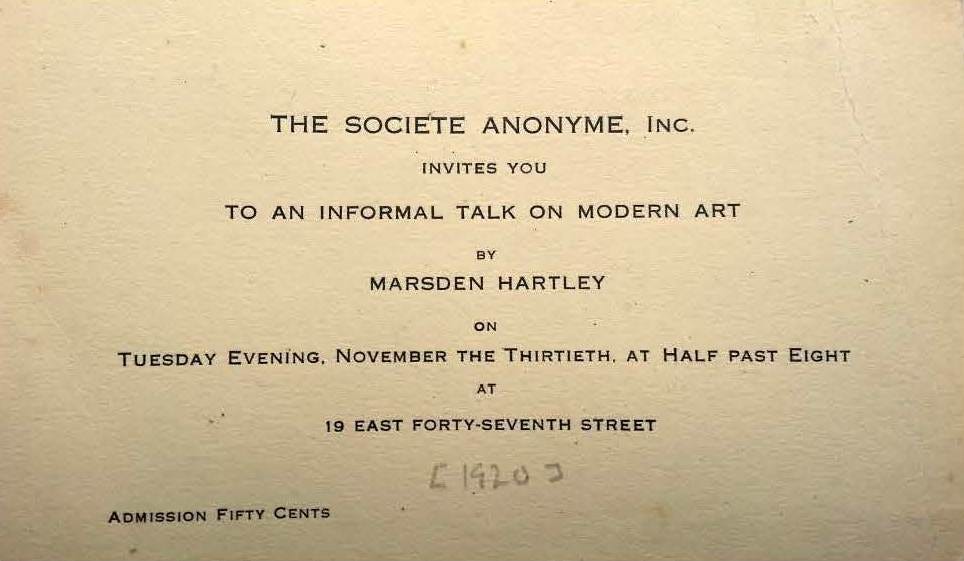

To our eyes, ninety years on, the paintings Cherry included in the group may not look particularly modern. Even Cherry herself, writing to Katherine Dreier, founder, along with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, of the ultramodern Société Anonyme, Inc, in New York (which Cherry joined in 1920, probably at the suggestion of Hartley), observed that her Reflected In a Mirror, which Dreier had seen in Cherry’s studio in New York, was “not advanced enough to interest you, of course.”

But at the time in Houston, San Antonio and even Denver, the concept of “Modernist” paintings, as distinct from paintings in general, would have been somewhat novel. And a distinct group of such works exhibited in the context of wide-ranging works by the same artist would have provided a clear visual encounter with Modernism that few in the local viewing public, including local artists, would have the opportunity to see otherwise. These exhibitions would have gone a long way toward establishing an awareness of Modernism in cities far away from avant-garde art centers in the eastern United States and in Europe.

Cherry showed 21 different paintings in the “Modernist Groups” of the three exhibitions. Thirteen paintings appeared in all three cities. In order to give us modern readers a sense of the “Modern” works contemporary viewers saw when they visited the shows, I’m including here images of those that can be identified, presented in chronological order by date of creation. Some titles are ambiguous, so it’s not possible in all cases to be certain a painting with the same, or a similar, title/subject was the one listed. Such ambiguous inclusions are indicated. Also, a few paintings that were not listed, but that are directly relevant to the discussion are included here and are so indicated.

Though ER Cherry may not be considered a leading Modernist in a global sense, through her art, her teaching and her exhibitions she brought the concept of Modernism in art to Houston almost single-handedly in the years 1920-1926. And by incorporating “Modern” elements in her own paintings, she showed other artists in Houston, Denver and San Antonio - and beyond - how they might become “more Modern” too.

“Now these modernists teach that painting is scientific from its very elements, and taking the prism as an instrument they study what they call the sequence of color and the relation of color to the landscape and nature especially under out of door conditions.” (Interview with Emma Richardson Cherry, Houston Post January 4, 1920.)

“Then I showed [Marsden Hartley] my modern flower one & he was very enthusiastic.” (Letter from Cherry to her daughter, Dorothy, September 28, 1920.)

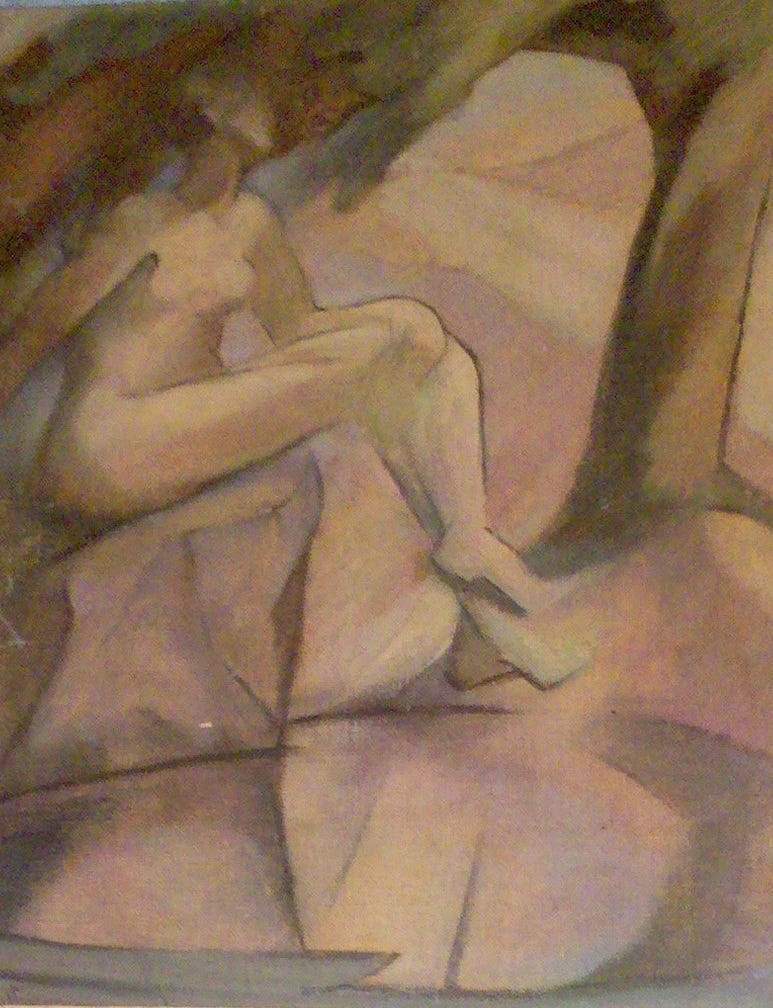

“[Hartley] started in on my wet paint & I can tell you it’s far & away a mighty interesting thing he is doing.” (Letter from Cherry to her daughter, Dorothy, September 28, 1920. Current research suggests that this painting, now lost, is the one Hartley worked on.)

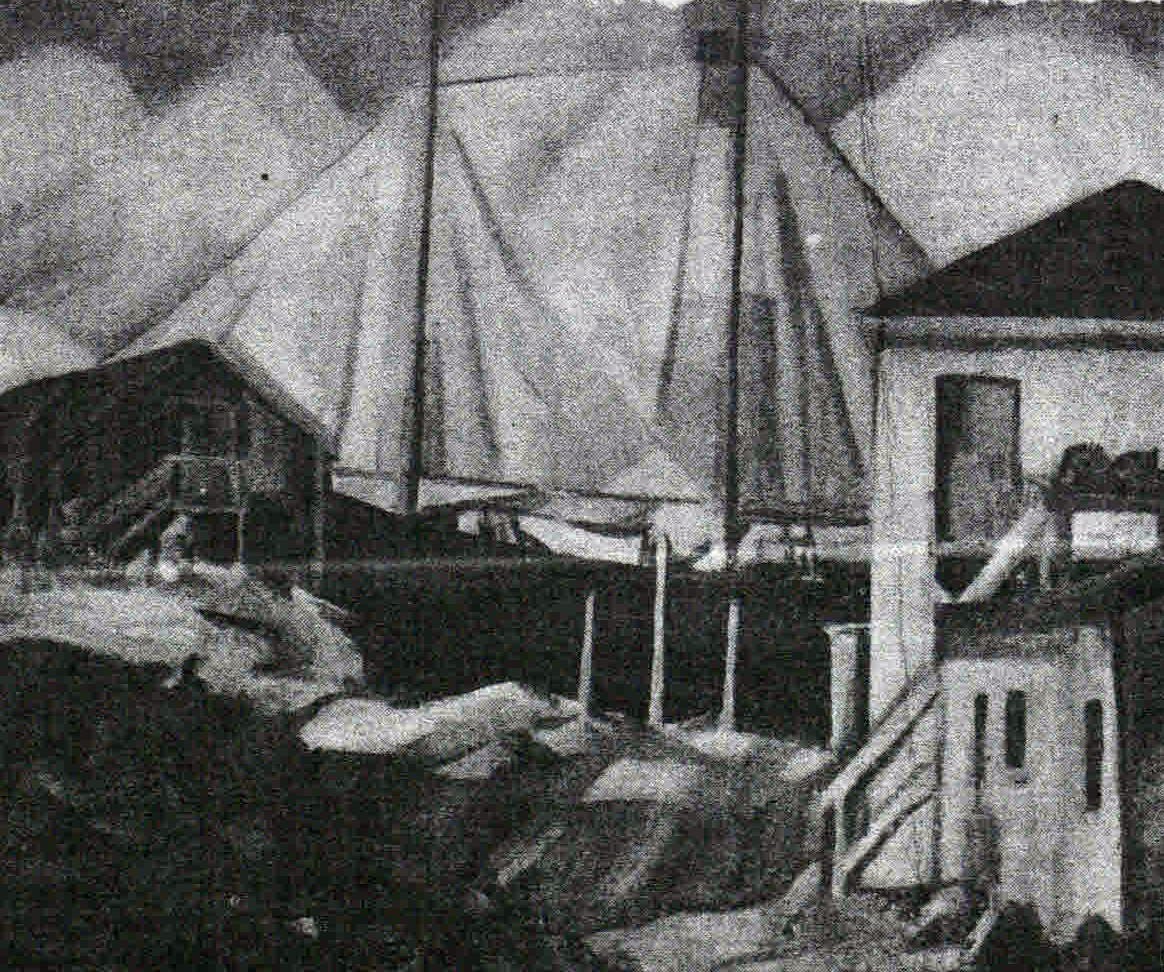

“… a compact block culminating in the spired church against the hills of Gloucester in carefully studied arrangement and color.”

The notation on the back of this painting, in Cherry’s hand, reads, “… second attempt at Modernism!”

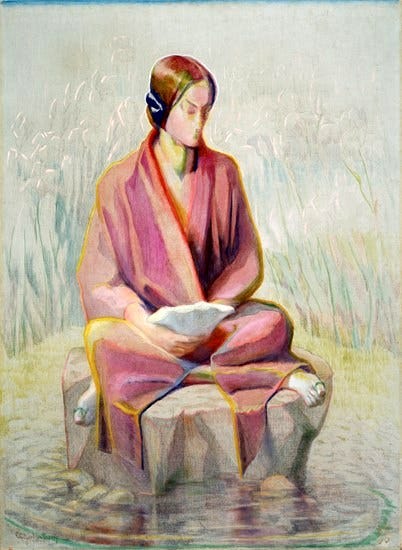

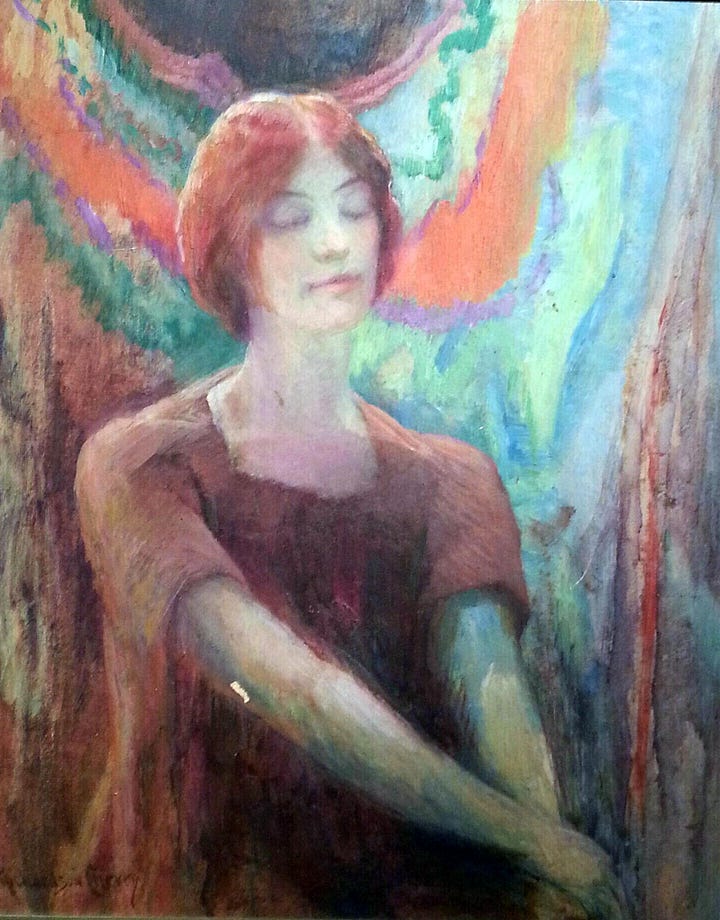

Cherry made this sumptuous painting during an extended visit with her brother and his family in Los Angeles.

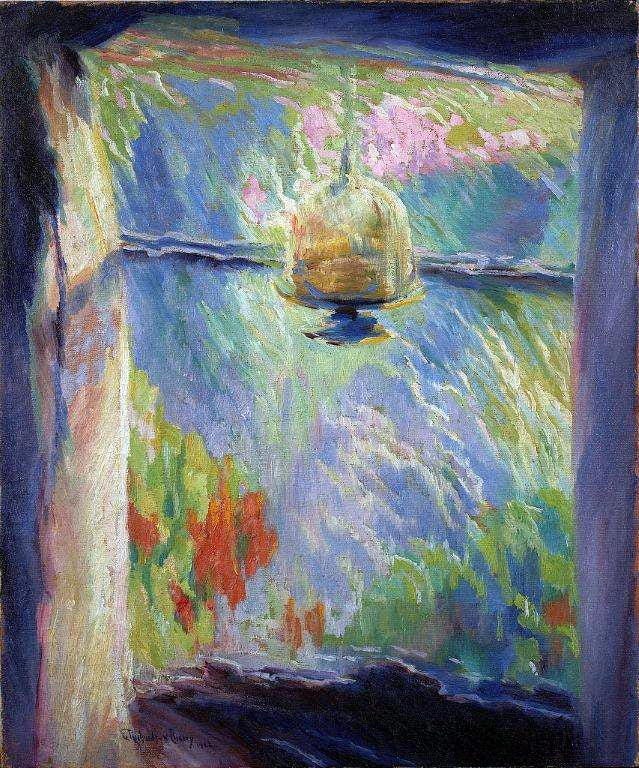

This is the painting which even Cherry admitted was “not advanced enough to interest” Katherine Dreier.

Emma Richardson Cherry, Color Sequence c.1923 (l), current location unknown; and Daydream c.1923 (r), published in Revue Du Vrai et Du Beau, Paris 1925.

“Mrs. Cherry painted it ‘only because she wanted to paint something that interested her.’ … The center of interest, as conceived by the artist, is the bowl, and the composition is designed to lead the eye to the bowl from every approach to the picture. It suggests pure idea, and is not intended to be symbolical.” (Houston Chronicle, February 1, 1925.)

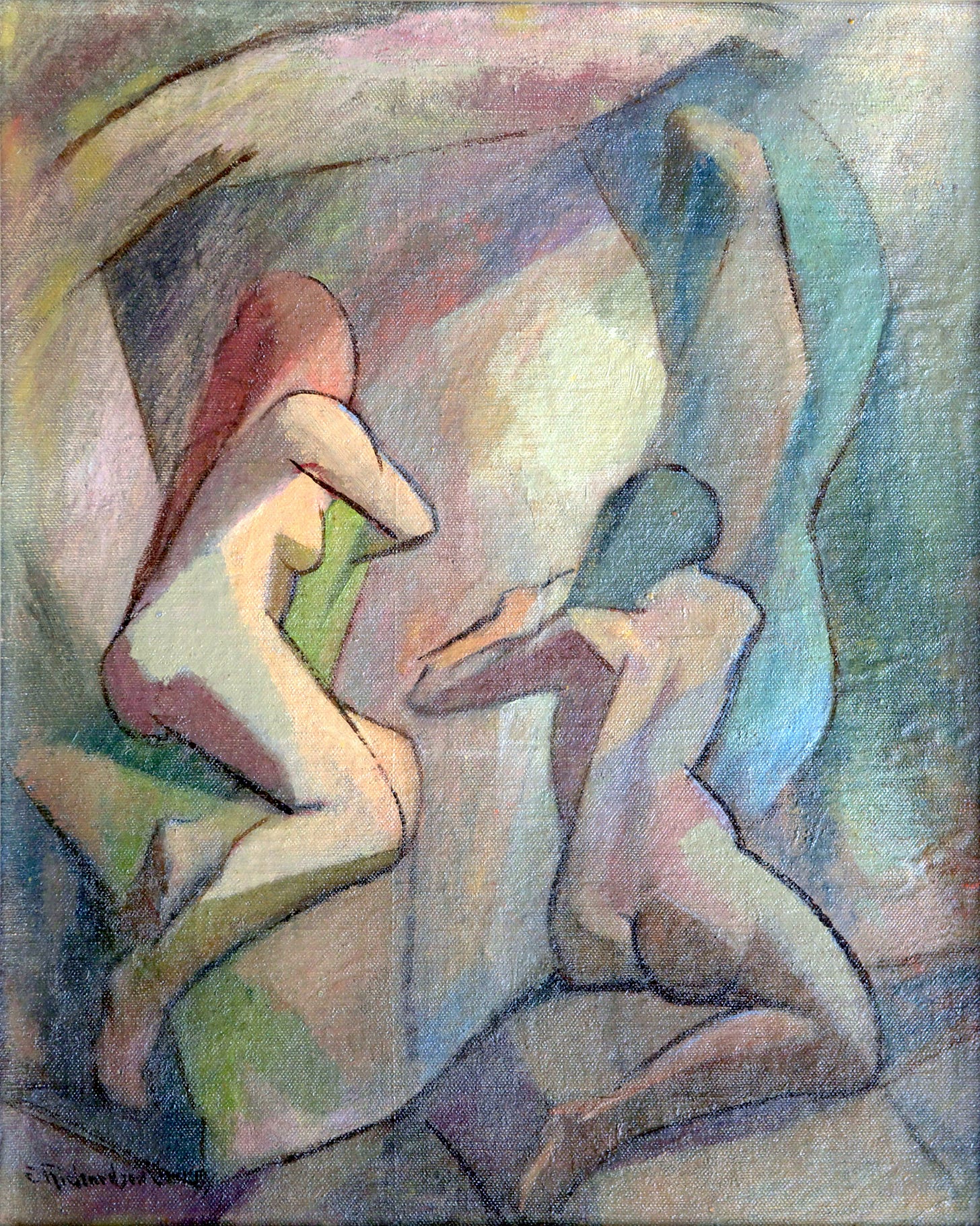

Cherry painted this, and the next two works, in Brittany during the summer of 1925. Her travel companion for the trip, also an artist, was probably referring to this work when she wrote in a letter dated August 7, 1925: “Cherry has torn loose and made her first modernistic picture, since our arrival – she’s as pleased as punch.”

Emma Richardson Cherry, Bourg de Batz, 1925 (l); Padre’s Walk [Maison du Cure], 1925.

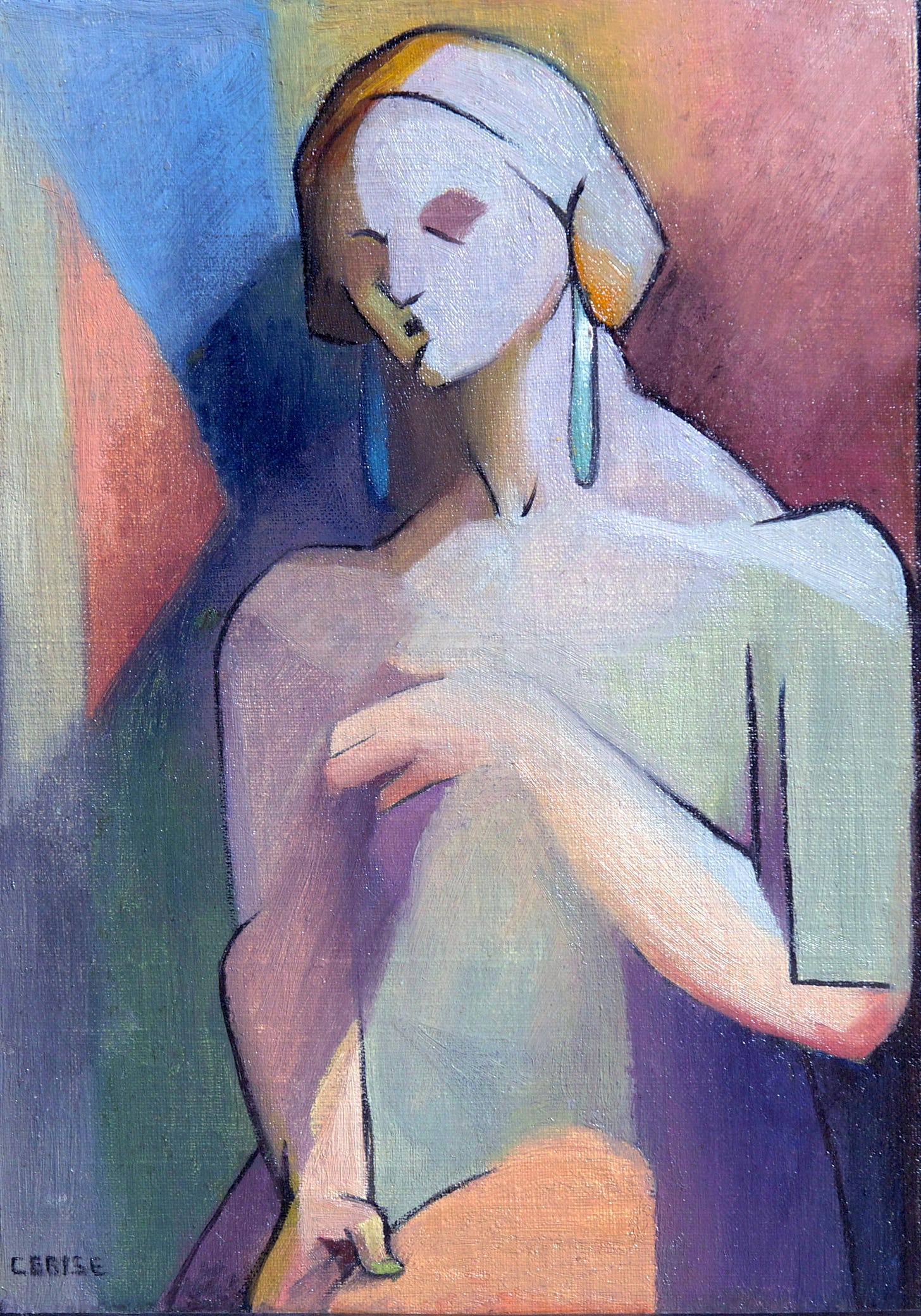

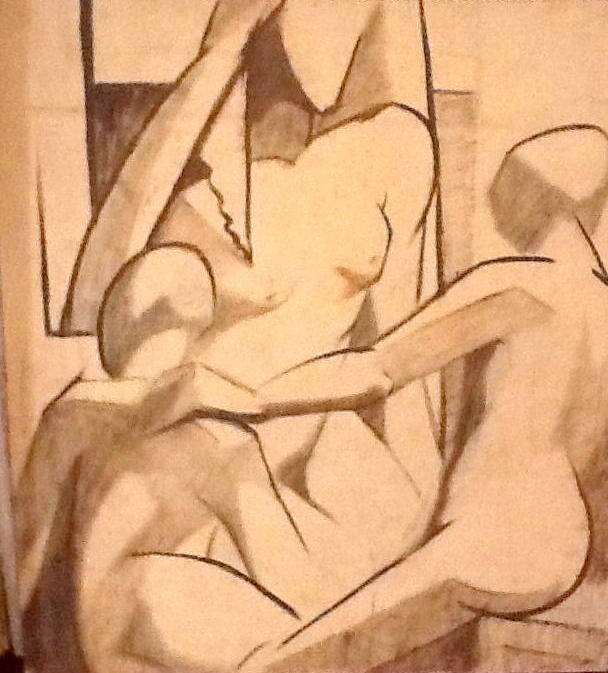

Cherry completed the four works that follow in Paris in 1925/26, while studying Cubism in the atelier of Andre Lhote and Dynamic Symmetry at Parsons Paris. Though the works are clearly Modernist in spirit, she did not include any of them in her “Modernist Group” exhibitions. They were, however, available for Houston colleagues and students to see (a mid-1930s photograph of her parlor shows Pan’s Pool on prominent display). They seem to be the first Cubist paintings by a Texas artist and relate directly to her Modernist experimentation.

In her later years, Cherry no longer broke out a “Modernist Group” when she showed her work. But in those heady days when Modernism was a new, amazing thing in art, she wanted to show the world - and perhaps herself as well - that she too was a Modernist. I think she proved her case by the work she made.