When the art is “constantly disappearing,” you’d best not dawdle if you want to see it. In a flash, it will be gone forever.

That’s the case with Marc Bauer’s RESILIENCE, Drawing the Line, his (which for a while, is also ours) 36-foot-wide wall drawing, in charcoal and pastel, that has just opened as the fifth installment of the wall drawing series at the Menil Drawing Institute. As with all works in the series, past, present and future, once RESILIENCE’s time is up, it will be painted over for the next drawing on the same wall.

So, even though RESILIENCE will be on the wall for 11 months, get over there soon (and often), because those months will be gone before we know it. And with this evocative work of “constantly disappearing” art (I quote the artist, describing part of what appeals to him about wall drawings, of which he’s done several around the world), now-you-see-it, then-you-never-will-again – except in photographs, somewhat ironic, since the Menil has a policy forbidding photos in the galleries.

I confess that I’m coming to this writing, and to the art, from a strictly personal point of view – not even any pretense of critical detachment. And I’ll begin with an anecdote to which the art itself is almost tangential: I went to the opening event, a dialogue between the artist and MDI curator for the exhibition, Kelly Montana, with my husband. And at the reception after, I met the artist – and HIS husband.

So what’s the big deal? you may be wondering. Well, this is what: When Bauer was a kid, in Switzerland in the 1970s and 1980s, never mind me, a kid myself in West Texas at least a generation earlier, neither of us could have imagined such a thrillingly mundane thing as being at an opening at a major art museum WITH OUR HUSBANDS! Back when we were young, we could hardly have conceived what that would even look like. There were no images of such a thing for us to model on. And then, there we all were on Thursday night, two sets of HUSBANDS, and it’s just the way it was. It almost takes my breath away even now, just saying it.

And now for a look at the art. There are big issues considered. The resilience of humans in the face of man-made watery disasters; the significance of images in finding a way of understanding the world and how we can be resilient in it; the search for an understanding of self in the personal context, past, present and future – but maybe especially past. For a little about those big issues, I’ll refer you to the Menil website for the show.

But I’m writing about my personal view. One of the important responses for me, as I look at the art, is seeing images of people like me – or at least like I was in some ways 60 years ago – young queer men (that’s the way I still identify, except for the young part) finding an understanding of self, and a place in a world, in which such images – images of people like us – have been absent, suppressed. I’ve written elsewhere about how important it has been to me, and how important I think it is to everyone (including, I suspect, the artist), seeing images of people like ourselves, as we develop our concepts of who we are, what we can be, how we can live our lives. There they are, people like me, front and center in Bauer’s drawing. How thrilling, once again.

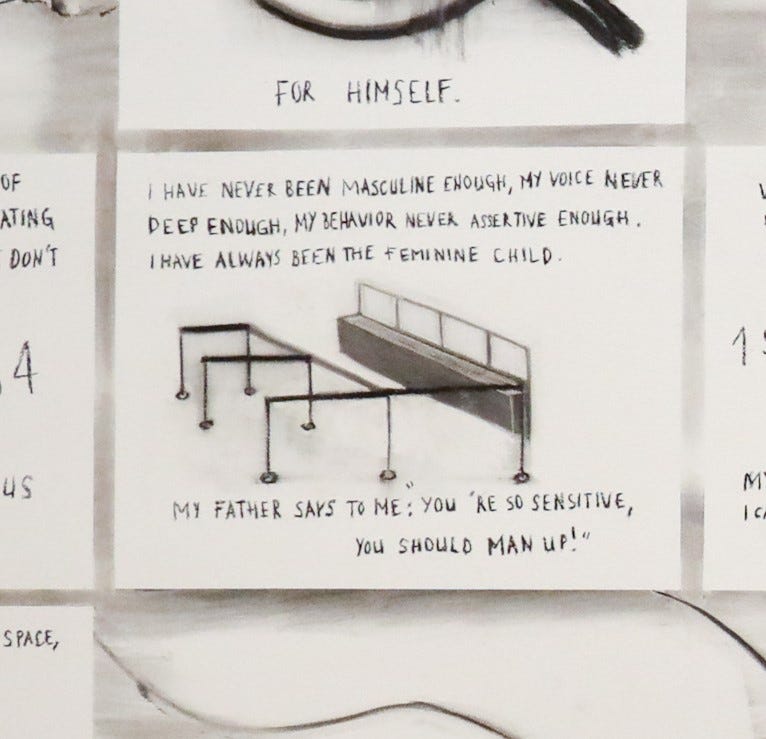

And when the artist says, in one of his searching-memory-for-identity biographical drawing/text inserts, “I have never been masculine enough, my voice never deep enough … My father says to me: you’re so sensitive, you should man up!” – I identify with the disappointing, devastating sense of difference the words convey, even though the particular words for me were different ones. Again, I’ve written about how knowing that difference impacted me. And even with Bauer’s global view of watery submersion, I make the global personal, remembering the disillusion, disappointment, need for personal resilience that my own youthful full immersion called out in a different context.

It takes a lot of nerve, I know, to make someone else’s art all about me – and then to write about it and share those personal views. But I think that interacting with art is, at the most fundamental, important level, a personal exchange. At least art that touches more than my brain, art that might make a change, whether large or small, in the way I am, not just in the way I think. So maybe making it personal is sort of OK, even if I don’t completely understand, get some of it wrong even. I hope Bauer, and also you, will cut me some slack, as I interact personally with his art at MDI. You can do the same thing yourself; I promise you reciprocal slack.

The drawing is filled with art historical references which I won’t pretend to understand (though I enjoy spotting them). There’s John Singleton Copley’s Watson and the Shark in the lower left. Remember the great show, American Adversaries: West and Copley in a Transatlantic World, which brought that magnificent painting to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, a decade ago? And there in the center is Botticelli’s Birth of Venus; and to the right, the writhing serpent from the classical Roman sculpture, Laocoön and His Sons. And an adapted Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault. Why are these, and so many others there? Aside from giving us the satisfaction of spotting them? I can’t say; ask the artist when he returns to Houston next year to make planned, but as yet unknown, changes to his drawing.

Yes, the artist, Bauer, will be coming back twice to change his “finished” work – a constant transformation before it’s preordained final disappearance. Sort of like life that way, when you think about it, don’t you think? Hmm. Could it be I’m beginning to have a bit of insight into what it all means? Both the art and life. Not likely, I suppose, but maybe.

One final, and yes, personal, note: as I stood in the Menil Drawing Institute, making my personal connections, whether right or wrong, with Bauer’s RESILIENCE, I thought of another sweeping work of art just steps away, taking up another vast wall all to itself, a work which, while very different from Bauer’s, has thrilled me in something of the same way for decades. I thought of Cy Twombly’s Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor), 52 feet across, with it’s explosions out of vastness, it’s touches of brilliant color, it’s passages of barely legible text. And so I went next door, to the Twombly Building, to look at it again – for the how-many hundredth time. Perhaps Twombly and Bauer would see no similarities to their works – aside, perhaps, from their vastness and their proximity for a little while.

But I’m talking personal. As I experience the two works at almost the same time, words that neither artist may have known come to mind, words that take me into another sphere, words of the English poet, Philip Larkin, the last lines of his poem, “High Windows”:

… And immediately Rather than words comes the thought of high windows: The sun-comprehending glass, And beyond it, the deep blue air, that shows Nothing, and is nowhere, and is endless.

That’s the way I feel as I look at both works, and it’s wonderful – even if I’ve got it all completely wrong.

Randy, your recollections and connections come from your heart, your spirit, which is so much freer now than it could be then, and I feel your joy and wonder in where you are now, along with the pain of the journey to get here. I love your description of encountering art on more than an intellectual level.