Left Bank on the Bayou - World on Fire

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

McNeill and I returned to Houston with a true case of the road “jitters” after the long drive, and with memories of many things, both exhilarating and unsettling, to work through in our minds. It was to be the last trip we would take for a long time without the specter of war hovering near. Even though the shooting war for us Americans would not come for two years yet, we all sensed that it would come eventually, and so it always hovered close, tinting everything.

McNeill returned to sad news regarding a “pal” of her son, Randolph:

“… our John – Frenchy, we called him," she said in her note, "– son of Dr. Mori of Rice Institute (don’t know how to spell the name) – has been killed in action in France. For two years he came to me almost daily in the studio and sat. Nineteen years old, so handsome and gentle. His father was so ambitious for him. He volunteered for the French navy and on the third day fell a victim.”Even as she mourned for her lost young friend, she feared for her own son, who would soon be of age to be sucked into the “blood and destruction.” And also her other boys, her art boys.

I commiserated with her that it might happen; it had happened before, as we both knew well.

“And ye shall hear of wars and rumors of wars: see that ye be not troubled: for all these things must come to pass, but the end is not yet.”That passage came to mind though neither of us were overly religious, in that way, I suspected (certainly I was not); but even so, perhaps the beauty of the language could give some comfort – and the reminder that the end – and the war – was not yet reality for most of us on this side of the ocean, for now.

I returned to a life, and a house, which both felt a little empty – or not empty, but somewhat lacking, now that I was again alone in them. I felt as though I had awakened from a pleasant dream – an oh so pleasant one – to find life much as I remembered it from before I fell asleep. Not awful, but ordinary, antithesis of the life in those pleasant dreams with Russell. Of course I knew that even if I fell asleep again, I could not recover that dream. It’s enough to hope that we might remember dreams – only the pleasant ones if we’re lucky – never mind reenter them.

And so I reentered the life from the time before Russell. Forrest had given up his studio-in-a-stable and gone back to Bay City, his hometown. Back to a closeted life – no, a celibate life, since he vowed to give up his life with other men “like him,” which his father could not have understood at all: he vowed to take no actions that might “hurt anyone other than myself,” he said.

But he had not cut all connections to those of us from his Houston life. In November, Gene and I drove down to Bay City where Gene would work with Forrest on murals for the New Texas Theatre, with the assistance of their flamboyant friend, Molly, a Bay City girl herself. The subjects of the murals – the pioneer, agricultural, industrial spirit of Matagorda – hardly seemed the likely inspirations for either artist, but “the coastline commands the horizon,” according to the newspaper description, a coastline Forrest knew well; and the design “centralized around the workman,” certainly an inspiration for both artists. I spent the days, while they painted, driving along the flat coast, through the endless almost empty stretches of marshland, watching the shorebirds swoop above the glistening water, and the occasional boat sail across the wide bay – and remembering that day, now long ago, in Seabrook (perhaps only a dream).

We all tried to believe that life went on as usual, even as we sensed the usual slipping away.

Our little band of artists continued to have success. Forrest’s painting Bread and Potatoes, which had already been shown at the Corcoran Gallery in far-away Washington, D.C., became part of the Houston Museum collection, a gift of the artist, true, but still eagerly accepted by the museum. And then, early in 1941, the museum hosted a one-man show of his work, to high praise from no less a critic than Houston’s own penetrating art discerner, Stella Hope Shurtleff, who saw, “the work of a man of vision … who gives evidence of having a future, it may not be an exaggeration to say, a destiny.”

Young Robert sent three works to the Exhibition of Houston Artists, that annual juried show of the best work made by those who were our own. Wild works, to be sure, by local standards, even wilder than those he’d shown already, building on the wild things he was learning in Chicago. But wild as they were, they won the annual purchase prize to become part of the museum collection too.

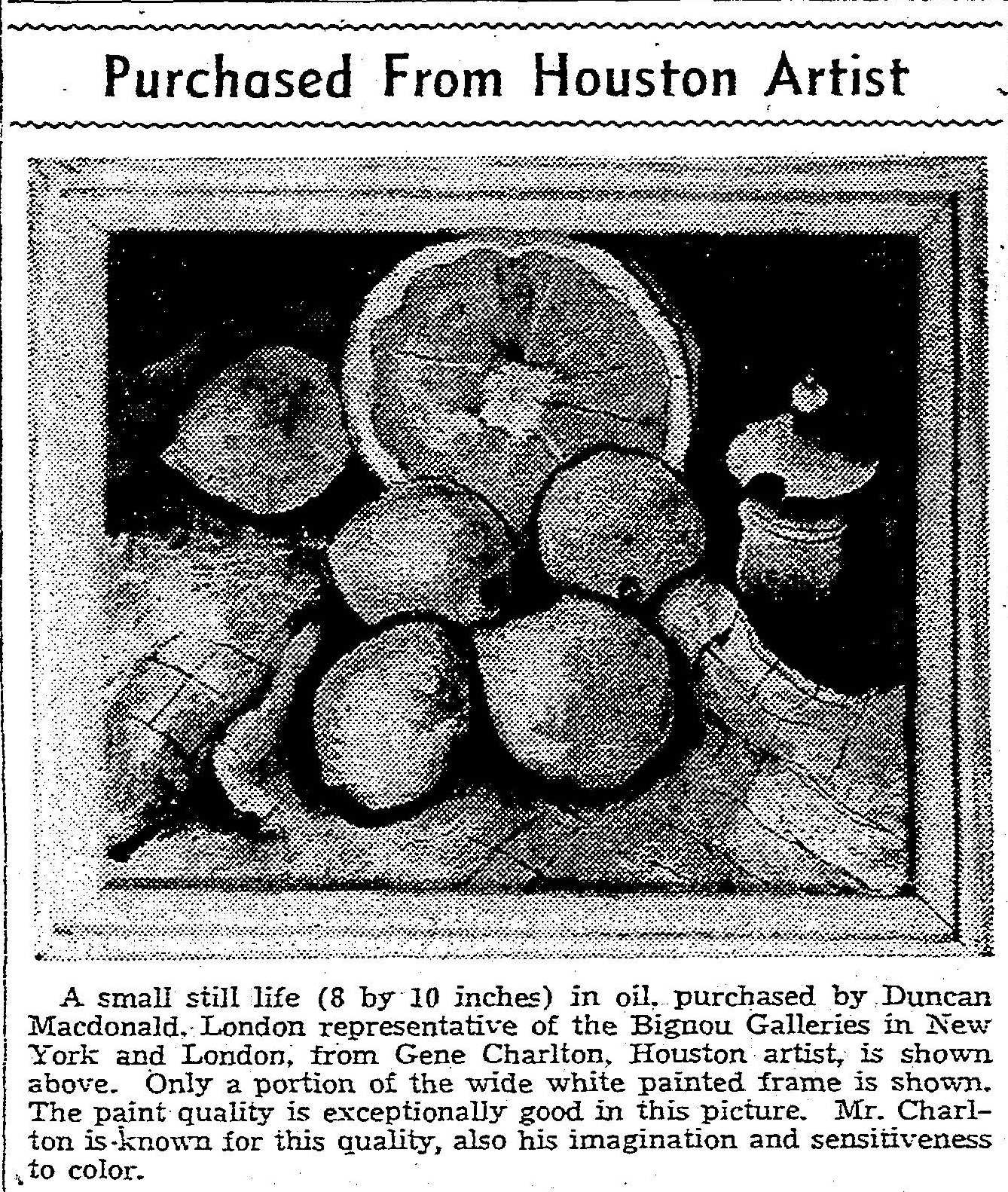

And at the very next Houston Annual Exhibition, Gene won the same prize, and also entered the museum list, for a group of three of his gorgeous still lifes of oranges and eggplants and roses, so richly colored and richly painted they seemed too rich for this poor life, more fit for an Arabian Nights or Pre-Raphaelite other world. A fourth of this beautiful group had already gone on to a life in the wide world of art when the London and New York art dealer, Duncan MacDonald, of the Bignou Gallery, bought it out of Gene’s studio (the studio he and Cardy shared), on a stop in Houston, as he toured America in search of art as yet undiscovered in the art capitals, art that could take its place there among the best. Gene’s work, so MacDonald said – and he would know – passed that test!

Some things seemed to go on as always: the sun continued to rise and set, the nights continued to go on interminably, the summers continued hot and humid, Margo continued to mount her plays – all unstoppable forces of nature in our Houston firmament.

But even so, I sensed that unrelenting thief, change, creeping toward me from all sides. With the turn of the new decade (making mine now a Queer Houston Story of the 1940s), I had reached middle age, no point in denying it. I felt it in my body – I no longer sprang eagerly out of bed in the morning, though still grateful I could get up at all!; and I felt it in my outlook – I thought of the past now at least as much as of the future.

I heard the sounds of construction in our booming city advancing toward my little acre, precursor to that day when I would no longer be able to afford to stay in Quality Hill. I’d talked already with some friends, rooted in Houston’s past almost as deeply as I, and, in the modern city, almost as irrelevantly, about moving my house, along with some others that might be deemed “historic,” to some graveyard of antique buildings somewhere out of the way of “progress.” But that was still only talk.

Forrest had departed for Bay City; Wilma had fled to San Diego, at the behest of her friend, the sculptor Mable Fairfax Karl (go WEST young woman, in quest of a new, free life!); Russell, of course, and all the hopes and dreams he embodied had gone. McNeill too left – “moved to the country for a more peaceful way of living,” back to her home ground, West Columbia, in Brazoria County, not far from Houston, but far enough that it might as well have been Mongolia when it came to the lost comforts of visits and long philosophical discussions.

And then, at the end of ’41, our world as we had known it exploded, as we had long known it would eventually, with Pearl Harbor and declarations of war!!

Then the changes came so quickly and from all directions; there was no chance of keeping up.

Over the next months, with mobilization, all our young men put on uniforms – and were gone. With so many of her leading men, and her supporting actors, and her set designers and stage managers vanished to distant places around the world, even Margo had to surrender. She left for Austin and teaching at the University in the fall.

Those young men all marched off with patriotic fervor, as so many had done in that last war, which, as it appeared, had not been the one to “end all wars.” Who knew which of these boys would come back when the war had run its course and the world had enough killing – what the world would be like then – what they would be like. Having lived through history made unavoidable the certain knowledge that some would not return.

The one solace, perhaps, would be that Mrs. Cherry had returned to Houston when her son-in-law, Major Reid, got his orders for a new posting, out of state. Her daughter, Dorothy, and grandson, Wally, would go with him, of course, so she no longer had any reason to stay in San Antonio. Even empty, the Cherry house still in Texas, still home, offered her a mooring. And, now that she would be back filling it, offered me a mooring too, a place of remembered pleasures and beauties, where the two of us could drink our tea, and talk of the past – Houston of old, Paris – and of art as we tried to help each other forget for little whiles that that past was gone, that change had stolen it.

A poignant story. I especially love Gene Charlton's art.