Left Bank On the Bayou - Mrs. Cherry's Grief

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

One lovely spring morning, when the magnolias had just begun to bloom, filling the air with their robust, almost cloying sweet scent – the reason Houston had become known as Magnolia City – I received a note from Mrs. Cherry:

“I have returned from San Antonio for a short visit. Only for the week. You may know that I have been living there, at Randolph Field, with Dorothy and Major Reid and dear little Wally, since Dillin’s death last August. I hope you will have time to join me for tea one afternoon while I’m here. I have so missed our tea-time talks.”

I accepted for that very afternoon by return note, and looked forward to it with anticipation. It had been such a long time since we’d visited – and so much had happened, for both of us, since the last time. For me, of course, there was Lorin. And then there wasn’t. A jolt, though perhaps not one of the major ones of life, considered in the long view.

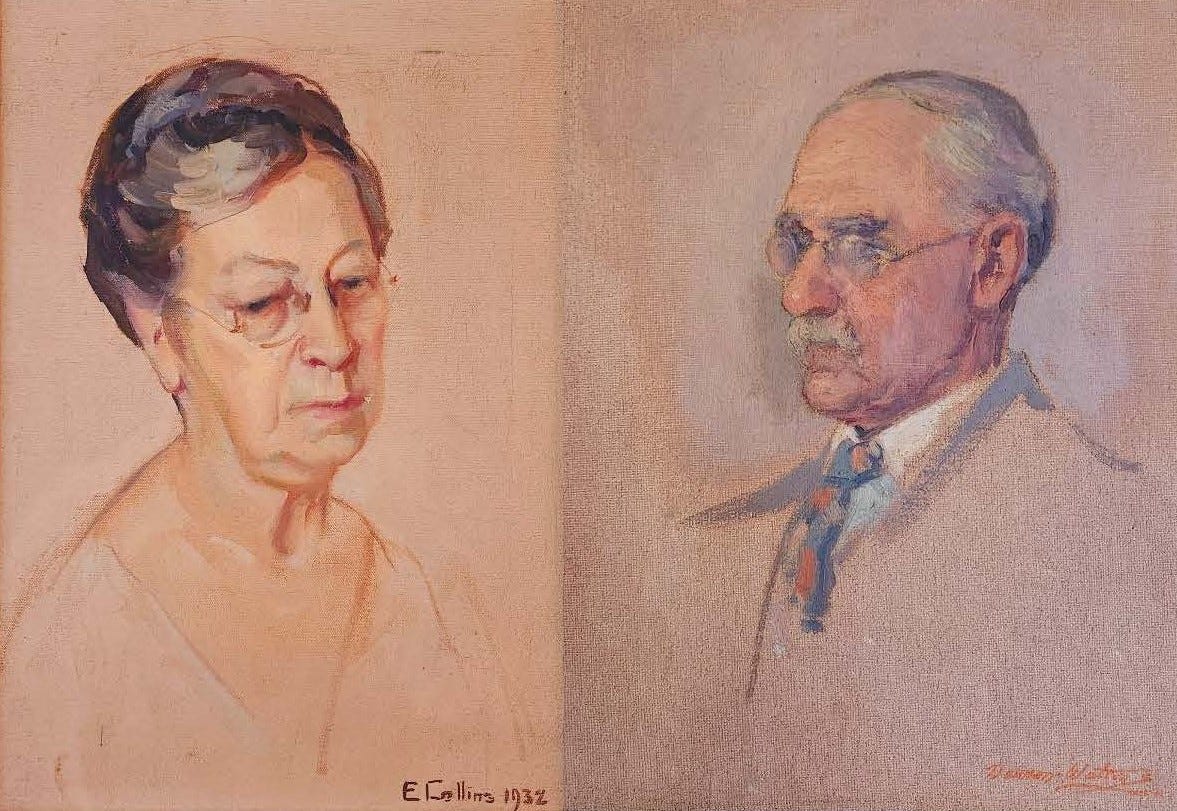

For Mrs. Cherry, not a jolt, but an earthquake. Her husband, Dillin, mate of 50 years, had died. A long marriage, never mind how unlikely a pairing of lovebirds many of us might have thought them. I knew that he had been in declining health. The times I’d gone to the Cherry House after my return from New York, Mr. Cherry had appeared only briefly, if at all. But that had hardly seemed cause for alarm – was not, in fact, unusual, since he had no interest in the things that we were likely to discuss: art, Paris, New York, décor.

He knew nothing about art beyond the fact that his adored wife made magnificent paintings, which, in his conviction, did not receive the admiration justly due them from the world at large, or the smaller world of Houston. He had never gone with her to New York or even Paris, where her heart lived, and had no desire to go there. And though he seemed to appreciate living in the Cherry House – in the exquisite setting she had created for them – one wondered how much of the richness and beauty surrounding him there he really saw. He might have been just as satisfied living the wildcatter’s life in oil fields yet to be discovered, fields he seemed always on the verge of finding, but seldom actually found. “Affable” seemed to be the term most often mentioned along with his name. But after that mention, for the real friends of Mrs. Cherry and her art, his name hardly ever got mentioned at all. No doubt he had a circle of his own friends in which talk of such things as blowouts and gushers filled the air.

But unalike as they might have appeared to outsiders (and who can really know what a marriage is about but those in it?), the two had been married for those many years. They married in Kansas City in 1887, only weeks before she left for her first visit to Paris – and Giverny, where she was said to have been the first woman to paint – leaving him at home. By the time she returned, two years later, home had shifted to Denver. They continued what had been for the two years, a very long-distance marriage; had a daughter together, Dorothy, their only child; and then, in the mid-1890s, moved to the Texas Gulf Coast where her family, parents, brothers, sister, and finally Cherry herself (born Richardson), had migrated until they were no longer the Richardsons of the mid-west – and, in the case of her brother James, Jr., of Yale – but the Richardsons of Houston and Galveston.

That Yale educated brother, James – said to be the father of Texas high school football, drawing on his Ivy League past when he came south to teach Latin at Ball High in Galveston – had tried by letter to dissuade her from making the move from Denver to:

“a mud-hole called Houston,” where there were “some nice people, of course,” but where even those were people “entirely without taste in house decoration and adornment … who can not tell the difference between a dollar chromo and a real water-color. I have always sworn by you,” he wrote, “as the one of the family having sense and reason. Don’t destroy that faith by a nearer approach to the Southern Cross – for it is a cross, truly,” by making such an ill advised move, where disdain for “Yankees” reigned, and the sentiment was, “We do all down here, reckon as how we don’t need no longhaired Yankee female to come and teach us nothing about pictchers …”

She had made the move anyway, and Houston – indeed all of Texas – had been the richer for it.

At the appointed hour I walked up the path through her garden of spider lilies and crepe myrtles, up the steps between white Ionic columns, onto the wide veranda, and grasped the knocker on the elegant, carved door. That door, so the story had it, had been all she thought she was bidding on at auction when she won the whole house – a home for the price of a door! – though one that had to be moved one late night on horse-drawn trailers through deserted streets from Market Square to this site on Fargo, then at the outer edge (or beyond) of tiny Houston.

As I waited, I turned, looking back out over the lush garden and wondering how much longer it would thrive, now that the master of the house had died, and the mistress had grown old and might now be sunk in grief. But that is life, and gardens may be almost as fragile as life itself.

Mrs. Cherry answered her own door, and welcomed me into her parlor with a handshake and a smile. Such a tiny hand, but how powerful when wielding her brushes. Once again I thought how her now-gone husband’s pet name for her, “Little One,” perhaps rang true as regarded her person, but in no way described her personality and her talent.

“Do come in. It may smell a little musty. I’ve aired the house, with the windows open and the doors ajar, but I’ve been away for months, so a day or two has hardly been long enough.”

I offered my condolences at her husband’s death.

“Thank you. He was a good man; better than most. He never begrudged me my art, or my travel, though both mystified him somewhat. We had our life together and our lives apart, and he accepted, respected both. Not many men with wives have the wisdom or humility to do so. I was lucky that he did. We were lucky, I like to think – and I think he would agree.”

I apologized that I had not been able to attend his funeral.

“You are kind and thoughtful. But I know you were away – in Santa Fe, was it? You may know that Rabbi Barnston did the service, right here in the parlor, though neither of us are in his flock – neither of us religious, for that matter, not in the church, or Synagogue for Rabbi B, way. But they were hearty friends, even though it might have seemed an unlikely friendship – much as ours might have seemed an unlikely marriage to many.”

I agreed that some attachments, though seemingly improbable, endure.

“Indeed. And how lucky are those of us who are blessed to be part of them. I say blessed, because blessings are not the property only of religion. Blessings can come even to those of us who are the most skeptical about those other things.”

I said I knew how much she would miss him.

“Oh, yes. Every day, full as each may be with other things, will be a little empty because he is no longer here to fill his part of it. Fill it with love, though he would purse his lips and shake his head at my using such a word – using it in the hearing of others, at least. He said it to me in private many times, even after many years. But men of his generation, most of them, balked at a public image of themselves as men of love. Lovers, yes. Even my Dillin had been an ardent lover once. I still treasure his letters from that time. But it was Dillin, that private man of love, I came to love truly. That is the man I will truly miss, and remember with a fond tear, now and again, every day, all the rest of my days.”

I said what a tribute I thought that to a man’s life, a husband’s life.

“And what a blessing to mine. There is that word, blessing, coming in again. But I’ve reached the age when counting blessings isn’t only a song to be sung on Sundays. And I know that I have many to count. Which makes me grateful, even in the face of loss.”

These were not merely saccharine sentiments said because expected at such a time and from a wife. Mrs. Cherry was not the sort for that. Had she not felt the sentiments deeply and truly, she would not have said them. I knew that after so many years of knowing her. I told her how I envied her that love, which would survive the grief, I knew. (To myself I said I hoped it would. But my envy of the deep love was real, no matter the pain of the grief that came with the death of the one loved.)

When she asked me how I had been, I told her of the excitement of the Ted Shawn Dancers, who had returned to Houston in December – twice in one year! I mentioned Lorin, a young man she did not know, as a passing friend. I said that I had met a man in Santa Fe, Russell, who would be coming to Houston when he finished all he had to finish there. I supposed she understood.

“Your own enduring love may still be ahead,” she said. “ But it will come.”

We had a long visit to make up for all those we’d missed since last summer. By the time I took my leave, all the tea cakes had been eaten, as had the sandwiches that followed them, washed down by beers from the time of Mr. Cherry, and in his memory. He had liked his beer.

As I walked back down the garden path to Fargo Street, it was growing dark. I stopped at the gate, and turned to look back at the house, shaded now in Impressionist purples and pinks, the golden glow of lights showing through the sheer curtains of the tall parlor windows. She had left the link between Russell and that enduring love unspoken, but I knew that she supposed I understood her meaning. And I did. And I hoped she might be right.

Randy, I have finally caught up with the story and have enjoyed learning about Mrs. Cherry and her art and your adventures back in your old home. I look forward to the next chapter, and, as always, following you on Facebook.

Kathy , one of your “Randy Readers”

Lovely.