Left Bank On the Bayou - Lorin Again

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

It wasn’t a dream. When I awoke in the morning he was there – still sleeping with the soundness of youth – sleep such as I had not known for years. Even the strong early sun, coming through the shutters, and striking his young face did not disturb his sleep. I watched him as he breathed soft, shallow breaths, and dreamed (perhaps) yearning young-man dreams, such as I had not known since (perhaps) before he was even born.

Once again, as I looked at him, I had the feeling that I had known him for much longer than just a few winter weeks – the feeling that I had known him my whole life, though I knew, of course, that wasn’t true. It wasn’t even that I saw myself in him, as I’d thought at first might be the reason for the feeling. Because of the War, my own course, at his age, had been a world away from his life now – literally a world, since it had taken me, at that young age, all the way to Paris, and to a first taste of life possibilities for men like us, so far away from the one he knew as to be not just a different world, but a different universe.

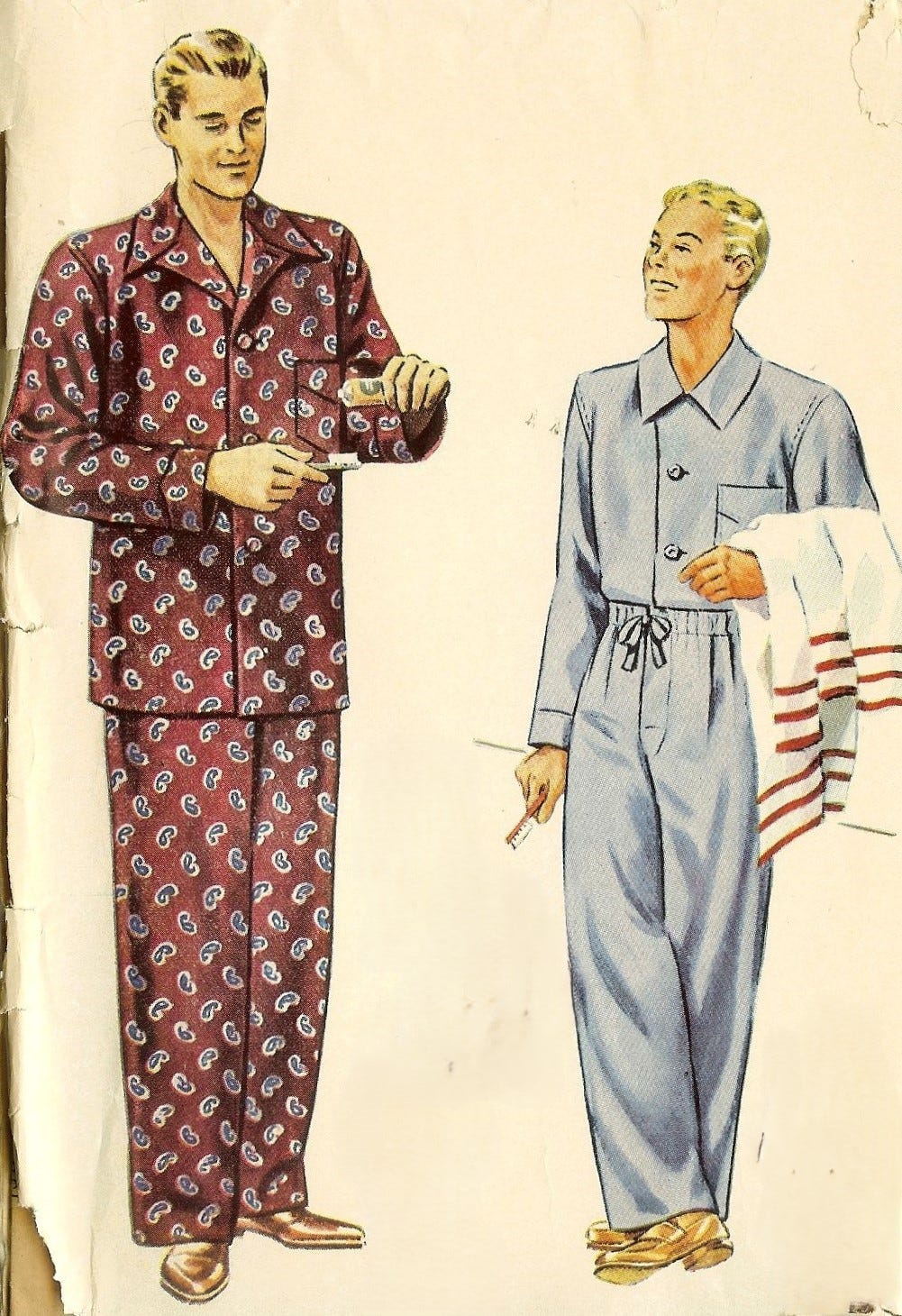

Since the night had been chilly, even in our Gulf Coast winter paradise (of sorts), I’d lent him pajamas when it came time to sleep – a loan at which he’d laughed at first – young men no longer slept in pajamas, he’d told me – as though his generation had invented the way young men slept. I smiled, knowing that I knew much more about the ways young men slept than he possibly could.

But since the heating in my antique house came entirely from fireplaces and stoves that would not be stoked through the night – none of that new central heating for my old-fashioned manse – and since no other young men need ever know, with only an old pajama-wearer there to see, he accepted the offer as the nippy night air dissipated the heat of earlier passion, and he snuggled down among the sheets beside me in an old pair of my old-man winter flannels. I would have told him they suited him, except that I suspected he wouldn’t want to hear it – and so I only thought it instead. But they did. And that they did only made him the more alluring.

“Will you stay for breakfast?” I asked him in a while, when he’d opened his eyes, and looked at me and smiled, after a few moments of obvious confusion as to where he was.

“I’d better get on home,” he said. “I have to get to work by 9. We’re putting in new window displays today, to replace the Christmas ones, and Eddie will NOT be happy if I’m late. Do you know him? Eddie?”

Of course I knew him. How could those of us in certain circles not know one of the chief window dressers of our town? Some clichés have enough truth about them to prove the rule without exception, and that window dressers were always (almost, anyway) men “like that” was not the exception here. And even though Houston had grown into a large city, the part of it that I lived in – with the others of “bohemian” leanings – remained a village.

He neatly folded the pajamas when he took them off, and I liked him all the more for it. When he’d left, I made myself a cup of coffee. By then the housekeeper, inherited with the house, in that repugnant Southern fashion that neither of us knew how to, or had the courage to, reject had been in to start the kitchen fire, before she went out again to do my shopping. I sat at the kitchen table looking out at the winter garden – still green, as gardens stayed all winter down here, but chastened by temperatures that had fallen into perilous depths overnight. I thought how lovely it had been in the cold bedroom, in the snug bed, the two of us there together in our (in my!) unfashionable, warm pajamas.

I wondered if he’d return to wear the pajamas again, wondered if, really, I even wanted him to. Some things are better left pleasant memories than forced to prove they can never be more. I knew myself, and life, well enough to know that I sometimes chose hope over reason, warm pajamas over cold reality, when it came to matters of the heart. “Not again this time, surely,” had become a standard phrase in my next-morning vocabulary, which even my next-morning self found it hard to think without a smile.

And so I smiled as I let myself think the pleasant thought of handing him the pajamas again, and then I took my coffee with me into the bedroom, and picked up the folded pair and put it into the laundry basket to wait for Monday, wash day, when my housekeeper would have two pairs to wash, instead of the usual one. I wondered if she would smile a knowing smile as she put them in the tub – or shake her head in a disapproving, unspoken acceptance of things as they were, bad as they might be, “Devil’s work,” as some said on Sunday morning. But some things, of course, remained unspoken, even though the understanding of all concerned did not require speaking them at all. Some day, perhaps, she would find the wherewithal to speak, or I would – but until then neither of us would even hint at things unspoken. Such was the covenant between us, inherited with the house and all that it embodied.

The next time I saw Wilma, I asked her what she thought of Lorin.

“He’s such a dear, sweet boy,” she said without hesitating even an instant. “Fragile, I think. But sometimes those who look to be the most fragile prove themselves made of unbreakable stuff. He may be one of those. Why do you ask, if I may ask? I thought you had a Russell already, to make such questions about other men – young men – irrelevant.” She smiled the knowing smile my housekeeper hadn’t.

“Purely academic interest, I assure you. Humanitarian,” I said, smiling, knowing that she knew otherwise. “We all owe it to the young to be their mentors, to ease their way in this bruising world, if we can.”

“Oh, give me a break, you old perv,” she said, with that sarcastic flick of wrist of which she was grand mistress. “I wasn’t born yesterday, never mind that I may look it. But both of you are adults – a term that clearly encompasses a vast span, since it includes you both – and so both of you can take care of yourselves. I will say that he seems quite besotted with Parker – at least the image and the idea of him – from what I’ve heard him say. But then you’ve been Parker’s rival before, no doubt, and so perhaps you know your odds. Do be careful, my dear. He may not be the only fragile one.”

Such talk of fragility and rivals seemed like high school chatter, ludicrous adolescent puppy-love melodrama, which should by now have been long-past for the worldly-wise likes of Wilma and me. And yet I knew that she said what she said half seriously, at least – and I took it to heart, half seriously (and more). I knew from painful, heart-piercing experience that some so called “adolescent” things could linger far into so called “adulthood” – no matter how “worldly-wise” that heart might think, or try to pretend, it had become.

Very cute story and loved the toothbrush moment and of course PJ. 🦷🪥

Wonderfully evocative. I think the image might be from a sewing pattern, Simplicity or Butterick. I still have a few for nostalgic reasons.