Left Bank on the Bayou - Of Postmarks and Smiling Spiders

A queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

I had long ago given up any hope that I’d receive another letter from Russell – the one that would make the reasons for his abrupt departure clear: I tried not to think of it as his abandonment. No, there would not be such a letter, could not be one clear enough to meet my need, so why even hope for it?

But one day toward the end of 1942, after all our young men had gone, and Margo had gone, and McNeill had gone, and Wilma had gone, and I had come to feel that the whole world I’d known had gone, I received an even less expected letter, this one with a St. Louis postmark. How I had come both to love and to fear postmarks over the years.

A letter from Clem!

It was not as though we’d become pen pals since that improbable (impossible almost, outside the pages of romance fiction) reunion at the Art Institute, now years ago. Certainly we hadn’t. There had been one Christmas card the first year, and then nothing more. I had not thought to send even a card myself, so had no grounds for complaint that there had been no more. Truth be told, I hadn’t even thought of it enough to think of complaining. Which was not to say that I hadn’t thought of them from time to time – on lonely nights, or at teatimes when Mrs. Cherry and I went back together to that Paris we’d all “always have.” But thought of a letter? Never.

This one I opened readily; no lingering in anticipation or dread.

After his greeting – more affectionate than I might have expected, but welcome as I read it – Clem wrote:

“Yes, St. Louis. Your stomping ground of old. Our Cellist (Clem, of course wrote the name, which of course I knew, but at first hardly comprehended as naming the man) has secured his cello chair at last, with the St. Louis Symphony. He pronounces it in the French way, much to the consternation of the locals, and sometimes of me. My family sold the business, and so, with nothing in that line to keep me in Chicago, and with a stake to set us up for the future, I had no reason not to join him in Saint Louie. So here we are.“We have an apartment in a semi-posh building in the Central West End – the Hawthorne, it’s called, built in the ‘20s, so probably after you left for Paris.“St. Louis is not Paris or even Chicago, as you will know, but not a bad place. He’s in heaven with his music, which, as you can imagine, makes life pretty heavenly for both of us. And we’ve met a few real doozies to pal with. One fellow in particular, now mostly in New Orleans, though back to St. Louis to visit his “harridan” (his word, not mine) mother. He writes plays, which are just beginning to take off. Attended Washington U, but long after you departed. (Can we be getting old?) Calls himself Tennessee, though what he has to do with that state is a mystery. Says he might have a chance with a woman director there in Houston, his agent says so, anyway. Margo something. If you know her, put in a good word. Even though you don’t know him. For an “old” friend?!“And if you ever make it to St. Louis, come visit us. Come stay with us; we have room. We’d both love that.”Wow! A letter to send me reeling, whether Clem meant it to or not. Me visit them? I laughed a sardonic laugh at even the suggestion. Clem, who could be a bit obtuse when it came to anticipating the feelings of others – and perhaps, even his own feelings – might not have considered how impossible such a visit would be. But My Cellist? He must know. So perhaps Clem dashed off the idea without even consulting him – just to round off a letter with the real intent of helping his Tennessee friend, an implied tit-for-tat: help my friend/bygones will be bygones. Which in itself might make a cynical spurned lover of the past wonder about his motives – had his letter been read by a cynical spurned lover of the past – instead of by me.

No, impossible for many reasons, not the least that Margo had departed, so I could not fulfill my side of the tit-tat transaction. And more impossible still because of the rawness still painfully there as I remembered that one lover had left me (abandoned me, not avoiding the term this time) for selfish “family” reasons incomprehensible to my heart, even if my mind might have entertained a sliver of understanding. And that the second lover had deserted me for the first. Some betrayals are too blazing to burn up pride, even if hearts might be able to be blind to them.

Heart, that old deceiver, with its web of heartstrings. Like Redon’s smiling spider, cocooning us in silk so that sucking us dry will be easier. By now I knew the trick and would not be ensnared again.

All tosh, of course. Of course I would be ensnared again! I remembered those first days with Clem, in Colorado Springs, when he despaired for his young dying wife, and I could give him some whisper of comfort. The days in Paris when we gave each other more than whispers, until he vanished. The days with My Cellist while the music played. And then the dark days, weeks, months, years, after I saw them together through the Gaudeamus window, and the music died. (Breaking the illusion with a bald anachronism, which time, however, will show to be not an anachronism at all. Sentimentality knows no shame.)

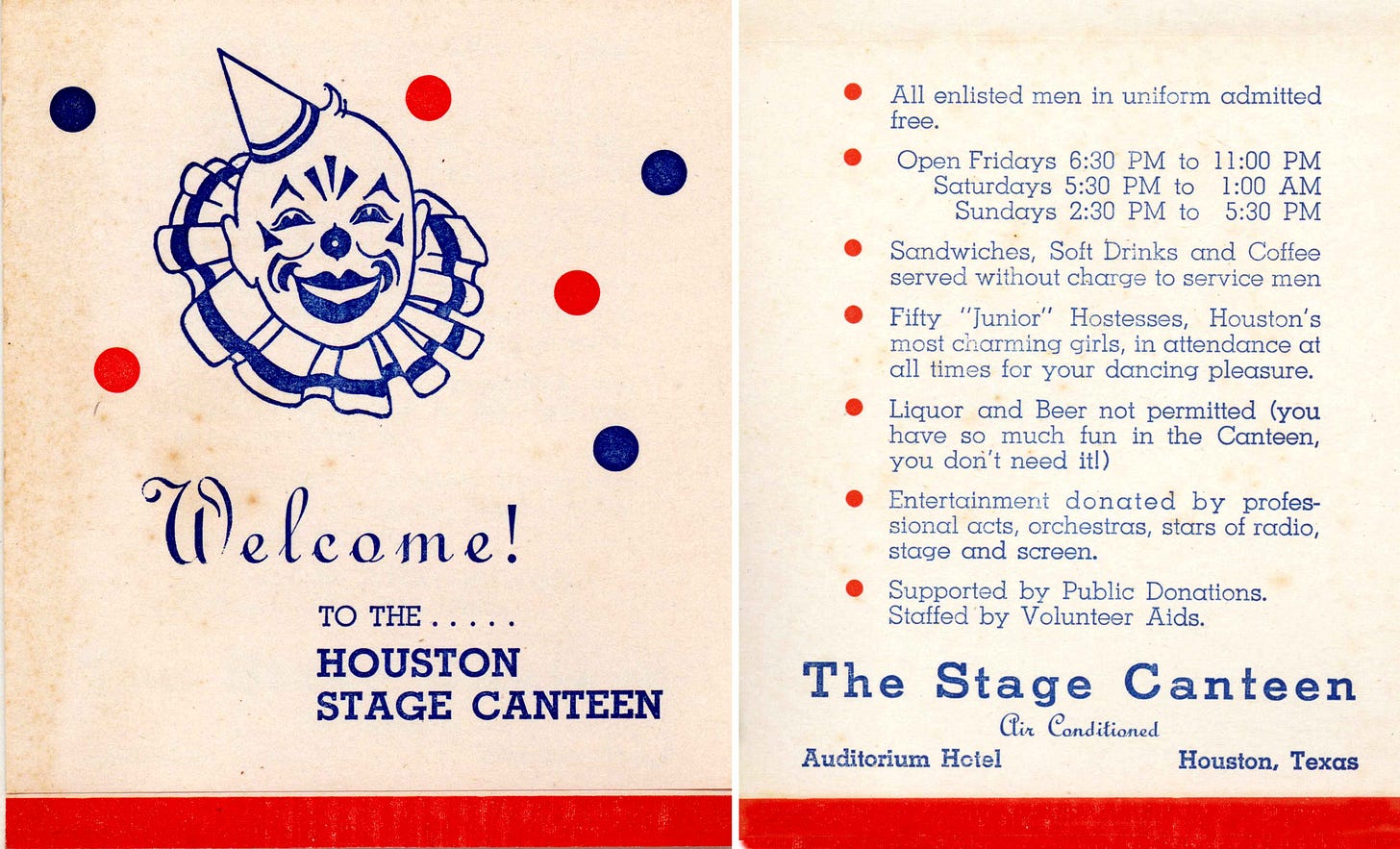

But it was New Year’s Eve, and opening night of our Houston Stage Canteen, which some of us had planned and built in the basement of the old Auditorium Hotel downtown, as a safe place offering some respite from the unsafe world they now lived in to the new boys in town in place of all our own boys now in other towns around the world – call them “boys” even though old enough to be in uniform, to be killed, to be dying on battlefields. I had joined the effort to make the Canteen a reality with my enthusiasm, and a little of my money. And so I would go to the opening night. I would put my own concerns on pause for the event; or I would try.

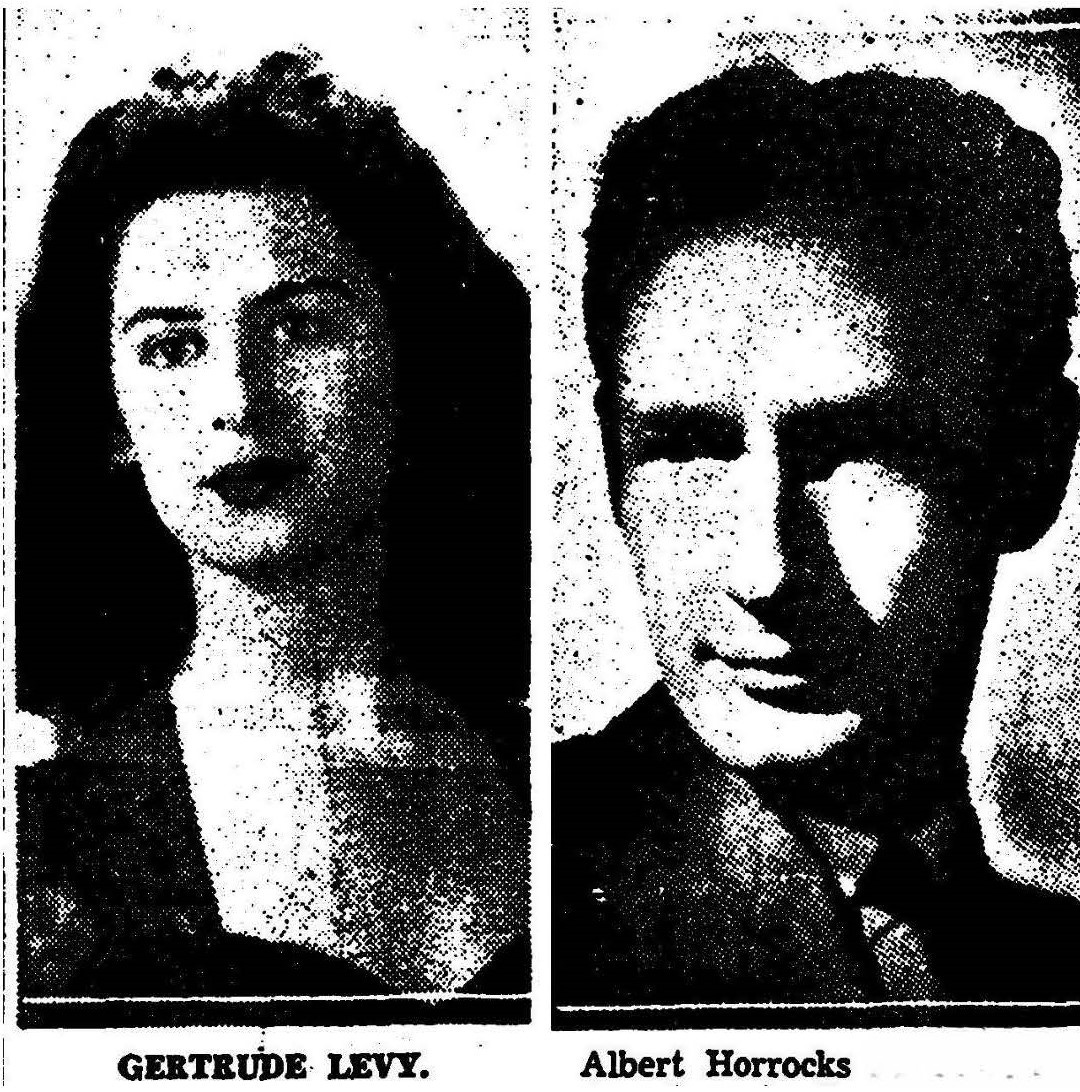

Many that I knew would be there: Lorin, stationed for now at nearby Ellington Field, who had painted the mural decorations – on a circus theme. Gorgeous little Gertrude Levy, a latter-days addition to our theatre circles, first with Margo’s company, and now that Margo had gone, with others – only 18, but such a beauty; I suspected she would be the death of equanimity for so-called “normal” Houston men for decades. She would likely be accompanied by that almost as gorgeous leading man, Albert Horrocks.

Who else would be there? Almost easier to list who wouldn’t be, from among the movers and shakers of Houston society now that war had limited the justifiable occasions for celebrating while others died. It would be THE event of this holiday season, giving those of us who were not in uniform, not risking death, a chance to put on our own dress uniforms of another sort and march (strut) for a few hours as though we too were doing our part. As I suppose we were, in a way.

Shut my eye, take a step and I'm there! You certainly capture the moments!