Left Bank On the Bayou - Farewell Party at the Stage Canteen

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the final part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

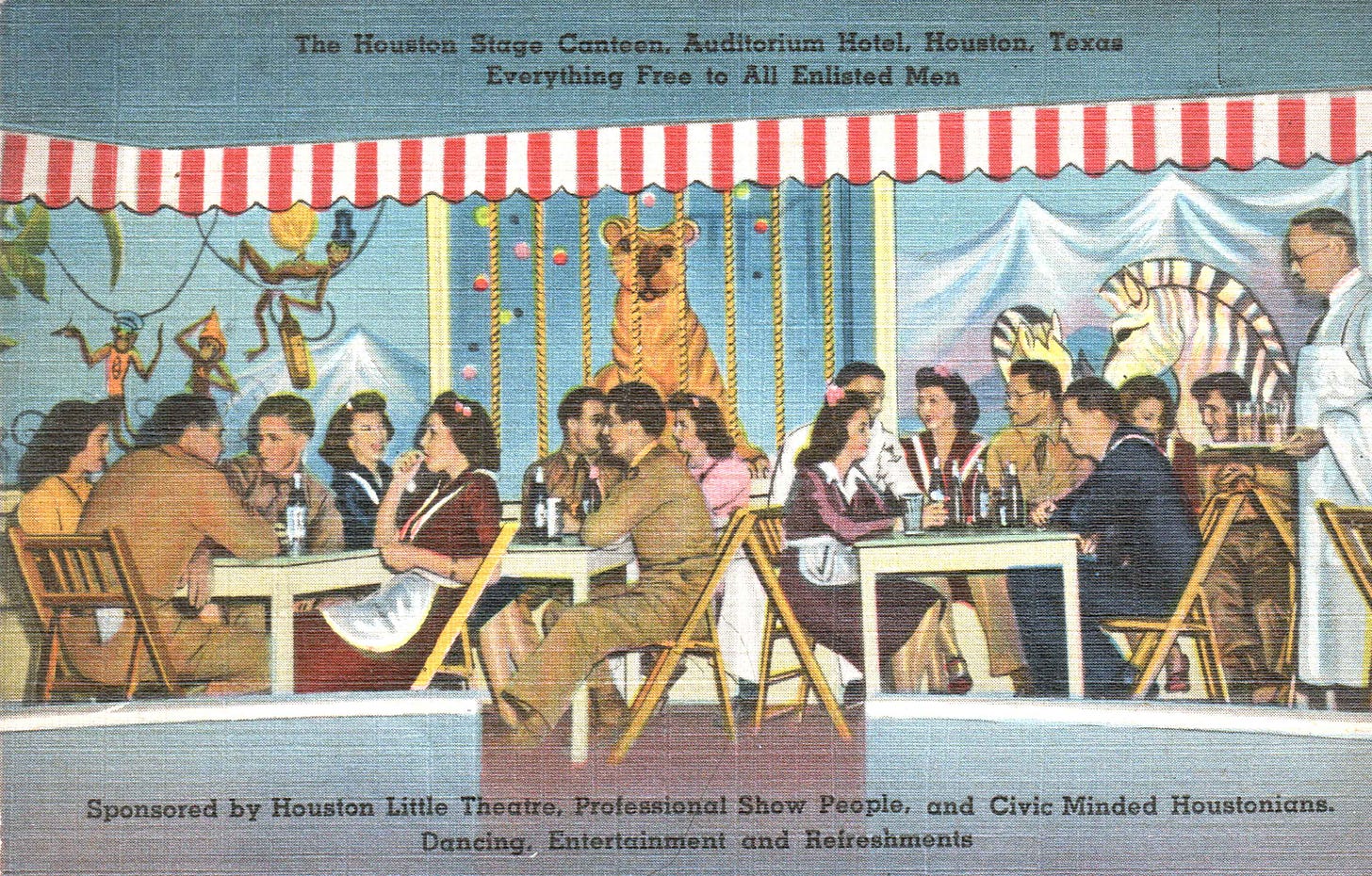

No chance of rain. Temps near 60. Parking a car likely a nightmare, with the crush. So not even a question: I would walk the few blocks to the Auditorium Hotel for the preview party at the brand new Stage Canteen, sure to be the “gayest spot in town,” according to the papers (though they may not have fully grasped all the meanings; or perhaps they did). This would be a rare chance for us civilians to party in the Canteen, those of us not in uniform.

We’d planned our Stage Canteen, patterned on those already opened in Hollywood and New York, but this one all ours, as a place for the young soldiers who so recently had put on the uniform, and been shipped far from home, often for the first time. At the Canteen they could spend off-duty hours in a welcoming, safe spot: no alcohol, no dark corners in smoky bars abounding with temptations to debauchery. Because some civic (and moral) custodians already foresaw potential dangers, evil dangers, with so many naïve – and some not so naïve – young men abroad in the world without mom or preacher nearby to keep them on the “straight and narrow.” A clean, well lighted place, as Ernest wrote in one of the spare stories that had made him famous since those days when I’d known him as an aspiring writer (though inattentive husband to Hadley) in Paris in the 20s.

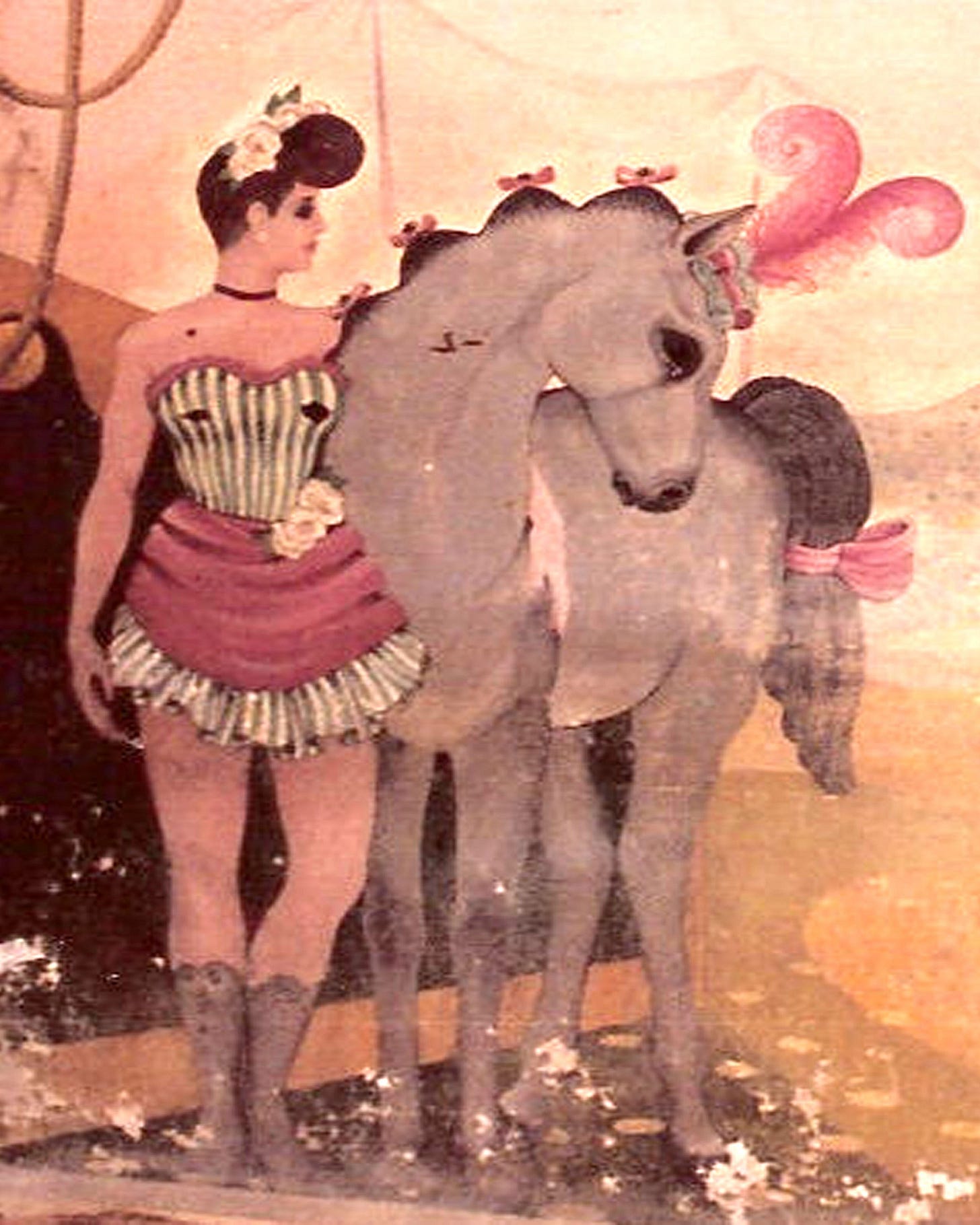

I might not have gone to the party at all, except that Lorin had painted the murals, on a circus theme, intended to transform the drab basement into a festive recreation space. I had not seen Lorin for some time, since before he, and most of the other “boys” of our Houston Art Bohemia, put on their uniforms in that great patriotic rush of enlistments that followed Pearl Harbor – uniforms that made them all look so manly – Lorin certainly so, if the photo of him in the morning paper a few days before could be believed. The picture made him look so much more a man than the boy-man I’d known those years ago; no less sweet in personality, but no longer tentative in person. I wanted to see the grown man in person – and in uniform, I admit it. As the artist (along with Ed, his newer friend and former window-dresser boss at the Fashion Department Store) likely he would be there.

I pushed through the Canteen door into a bright room filled with revelers in finest feathers, at work making merry this special evening, a gray A-list of Houston civic citizens – not the cream of society, perhaps, but those who felt a mission to work toward what they saw as betterment for our city. Exactly the crowd I should have anticipated, but somehow hadn’t. Lorin’s murals surrounded me on the walls, but I did not see Lorin, nor any of the other intimates of the life I had built in Houston since coming “home.” With all the others gone their different ways, it seemed that I alone survived to remember that life.

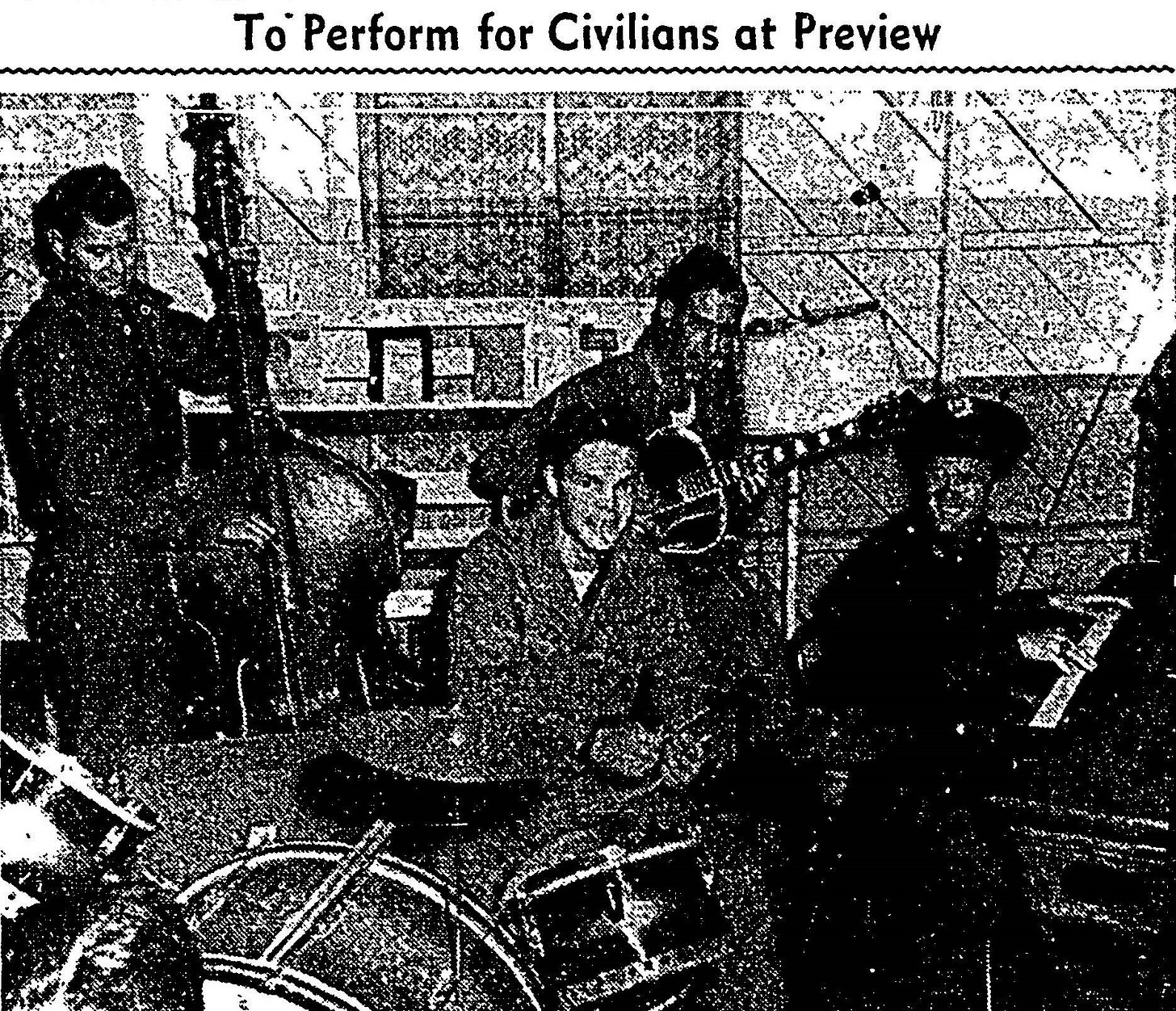

From the stage, the fast and furious music of the Ellington Field Jive Band; on the tiny dance floor, simulating a railed-in circus ring in keeping with the decorative theme, couples (boy/girl couples only, of course, and all white) cutting a rug with the latest dance steps – steps I had long since failed to learn.

In a while, the crowd parted – nothing Biblical, only the currents of flow around the room – and I saw Lorin far on the other side, ebullient as he basked in the praise of his murals from the circle around him. Murals that created “a circus in miniature,” according to the newspaper write up: “… amusing decorations done with skilled artistry. Brilliant-hued tigers and lions, caparisoned horses, clowns, figures of aerialists, and even a ferocious gargantua behind the bars, adorn the walls bordered by red and white canvas.”

Slowly I made my way across the room, in his direction, but not toward him, so that perhaps he would not notice, saying a word or two to many as I went, becoming an actor playing a part that called for nonchalance.

As I came closer I heard him talking, in the sweet happy way he had when not overshadowed by the troubling things of life: “Who would have thought that the Army would order me to design sets? Amazing! They even want me to do sets and costumes for an original musical comedy to tour bases all around the country. Maybe even overseas. The book is not very good – I’m being kind – but the music is very, very good – several numbers that you’ll love. I’m only a private, so I couldn’t say NO, of course. Already I know, when the Army asks, privates say YES. Not that I thought of saying NO even for a minute. To tell the truth, my commanding officer at Ellington Field is a lot less commanding than Margo ever was.” He laughed, and the sparkle of it melted me.

Seeing him again, so close, manly in his uniform, bubbling happy, as he had not been after that troubling talk that last morning at my house, I felt a surge of desire, as much for all the men I’d ever desired – as much for Clem, My Cellist, Russell, the Lorin from then – as for the Lorin I saw standing just over there, now. And also felt a longing to be desired, by him and them, as ultimately I was not. A desire to be desired that lives apart from sex or love, seldom thought of, but always present from birth to death, I suspect. And for most of us – perhaps even the most desired – seldom satisfied.

Ed stood beside Lorin. I saw the backs of their hands touch briefly. Most of those in the circle would not have noticed, or would have thought nothing of it if they saw. I saw. I knew that I would not find the desire I pined for, there, that evening.

As I walked the few blocks through the mild night back toward my house, I thought back to those times with Lorin; and those with Russell; and those with so many others before them, in New York and Paris. Not so many, in fact, but more than a few. I thought back to them with a tear.

I sometimes (often!) suspect that in my constant rumination on life and love, I plumb the shallows of sentimentality, more often than going for depth. But how much better are seriousness and depth, really? Have they saved the world yet? I read once about a young man who died of melodrama. I was touched but thrilled. The fact that the text actually said “melanoma” made even death seem almost mundane when I realized my mistake. After all, it might not be such a bad thing to die of melodrama.

Even without champagne, and a day early, this would be my New Year’s Eve for 1942. It had not been the youthfully (can we call it that) innocent (I blush to say it) New Year’s Eve at Wilma’s not so very long ago, when I first met her band of gay boys, and first saw Lorin. Or the New Year’s Eves in Paris; or the truly innocent ones still further back. But even the most delirious deceiving heart could not raise hopes of a return to New Year’s Eves like those. Older and wiser as I had become (remarkable how older and wiser is an ever-moving target), I now knew not to wait for the return of such past innocence. Youth had long-since flown.

“Old time is still a flying,” no denying it. But I hoped that perhaps I might still have at least a little time left for gathering rosebuds, even if slightly wilted ones. I was not dead yet, either from melodrama or anything else. I still had a future.

Such was my cri, or at least whimper, de coeur – perhaps that whimper Eliot mentions in his poem.

And yet, as I walked past the mirrored kiosk on the street in front of Levy’s Department Store, and caught the eye of a young man in uniform, “combing his hair,” a young man here to take the place of one of our own young men in uniform, perhaps gone to wherever this young man came from, to replace him for a while, and as the young man’s eye quickly glanced away toward another young man, also in uniform, also from someplace else, my whimper-de-coeur trailed away into a resigned, and somewhat humiliating, whisper. I picked up my pace a bit to get back to my empty house sooner.

New Year’s Day, I went to tea with Mrs. Cherry.

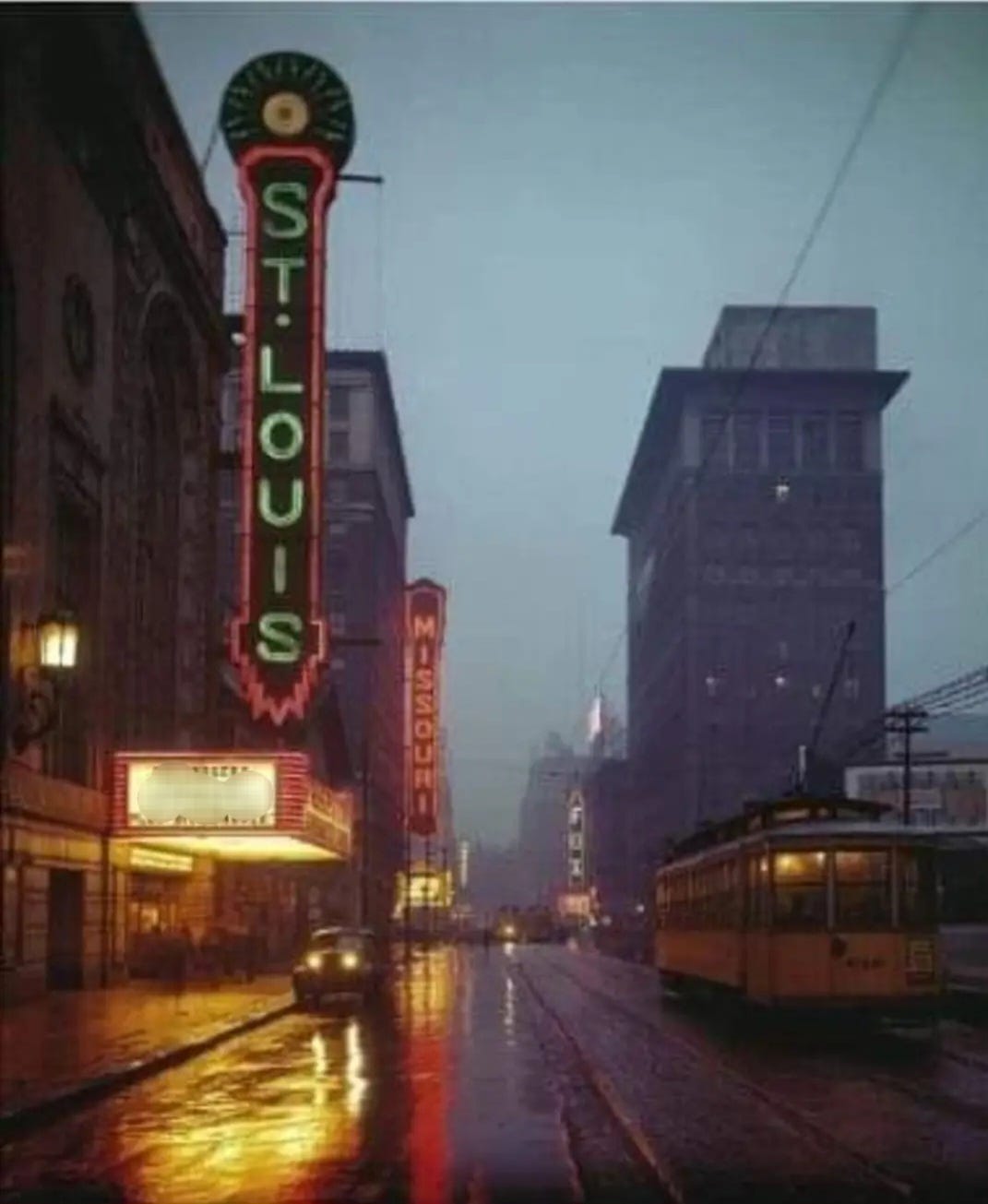

“St. Louis?” she said, a bit as though she’d misheard me.

“Yes, St. Louis. You know I went to college there, to Washington University, back when it was almost new – and I was too. I haven’t been back in decades really. McNeill and I stopped there briefly when we took her young Robert to Chicago, to the Neu Bauhaus. But otherwise, not.

“But I’ve had a letter from my old friend, Clem. The fellow you met at the theater in Paris, the Josephine Baker night. Do you remember?”

She said she did.

“Baker is originally from St. Louis, you know. But that’s neither here nor there. Clem and My Cellist live in St. Louis now, and he suggested that I visit. At first, of course, I thought that preposterous, impossible. Perhaps you know why.”

She said she did.

“But then I thought, Why not? Perhaps I’ve done all I need to do in Houston, at least for now. I know that I’ll never leave it completely behind, just as I’ll never leave Paris. The past is not past so long as we’re here to remember it, to continue living it in our present. But sometimes the past can be too present. I’m beginning to feel that – in my house out of the past, and even in this city primed for the future. With almost all of those who made the city home for me again after I returned, now gone – except for you, of course, chief among them in easing my return – but with so many gone, and stuck as I feel, almost drowning, in that past, and since I now have friends in St. Louis, even though friends with whom I also have a past, I thought, Why not? It might be just the goose I need to get me looking towards the future once again.”

She agreed it might.

And that night, when I got back to my empty house, I wrote Clem a reply, which I would post first thing the next day: “I accept your invitation. I hope you meant it. A new year, a new adventure. I’m on my way!”

The end … for now.

We want more!

Amazing! To be continued…😇