Left Bank on the Bayou - Faltering Next Steps

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

In the end, I did not run off in search of Russell to any of those places I heard that he might be. The inertia of heartbreak, and of experience, proved enervating. Even staying in place seemed almost more than I could manage. And so I stayed in place, befuddled, distraught, heartsore.

Or was it the beginning of wisdom that kept me from going – that faux wisdom of abandoned lovers born of bitter déjà vu, knowing that they would be fool’s journeys whether I found Russell at the end of them, or I didn’t?

No more letters from him arrived to further amplify his references to Proust. The hearsay of his possible destinations stopped being rumored; our mutual friends stopped asking if anyone had heard; soon even his name stopped being mentioned, in my hearing anyway. And with that, he disappeared from our Houston world – my whole world, as it still felt in my darkest, loneliest hours – as though he’d never been part of it at all.

In April, I went to see the Houston Annual Exhibition at the Museum, of course; we all went to that one every year; so many of our artist friends always had work on show there. Amongst the many canvases by those I knew, what a shock to see two by Russell, including the one that had so recently hung in my dining room. So he hadn’t removed it just from some inexplicable spite. It seemed almost as though he hadn’t gone away, that I’d turn and see him coming toward me as I looked at his painting, his smile broad with pride and love as he came up beside me. But when I turned to greet him, he was not there. Of course he was not.

At the least though, the Museum would have an address for him, the place he’d be to receive his painting when the show was done. I could ask my museum friend for it – the address, though I longed to ask for the painting too. But I wouldn’t ask. If Russell didn’t want to give it to me himself, for whatever his reasons, I had no right to get it elsewhere. And no desire to. If he had let go, I must let go too.

When I turned back to the painting, the tears I’d struggled so hard for so long to keep from flowing, flowed despite my struggles. At last. I should have shed them weeks ago, to wash away the image of him that had been always in my eye since his vanishing, even as I tried doggedly to see beyond it, see the world as it now was, without him. Perhaps the washing away might help me with the going forward, with taking the faltering next steps I needed to find the courage and the footing to take.

Now, at last, I even continued my unfinished letter to Wilma: “Oh, Wilma, yes again. But perhaps you already know? Perhaps someone has told you? Russell has gone. Gone where, I have no idea. He didn’t tell me, didn’t tell me even that he was going, never mind where.

You, of all my friends, know the pain I’m feeling. I think often of your beautiful, burning poem, “Heartstorm,” the one you published in the Houston paper all those years ago – when we were young and foolish:

What shall I do? I love you – And it is too late now To turn back. Oh, what shall I do? My eyes are filled with bitter tears From loving you In vain. Do you not guess That my heart is breaking?

Forgive me if my own heartstorm garbles your searing words a bit. Know that your words, however garbled, have kept me almost sane in this time of bewildering love-insanity.

I thought of simply quitting when Russell left. Of calling it quits for a life of more than the basics: eating, drinking, sleeping, weeping. Loving – trying to – had proved almost too painful. But again you helped me, with your words, the lines you end your poem with:

Well I will try –

And perhaps some day

I may learn to forget

May even be happy – perhaps.

Perhaps. Probably. Some day. But when?”

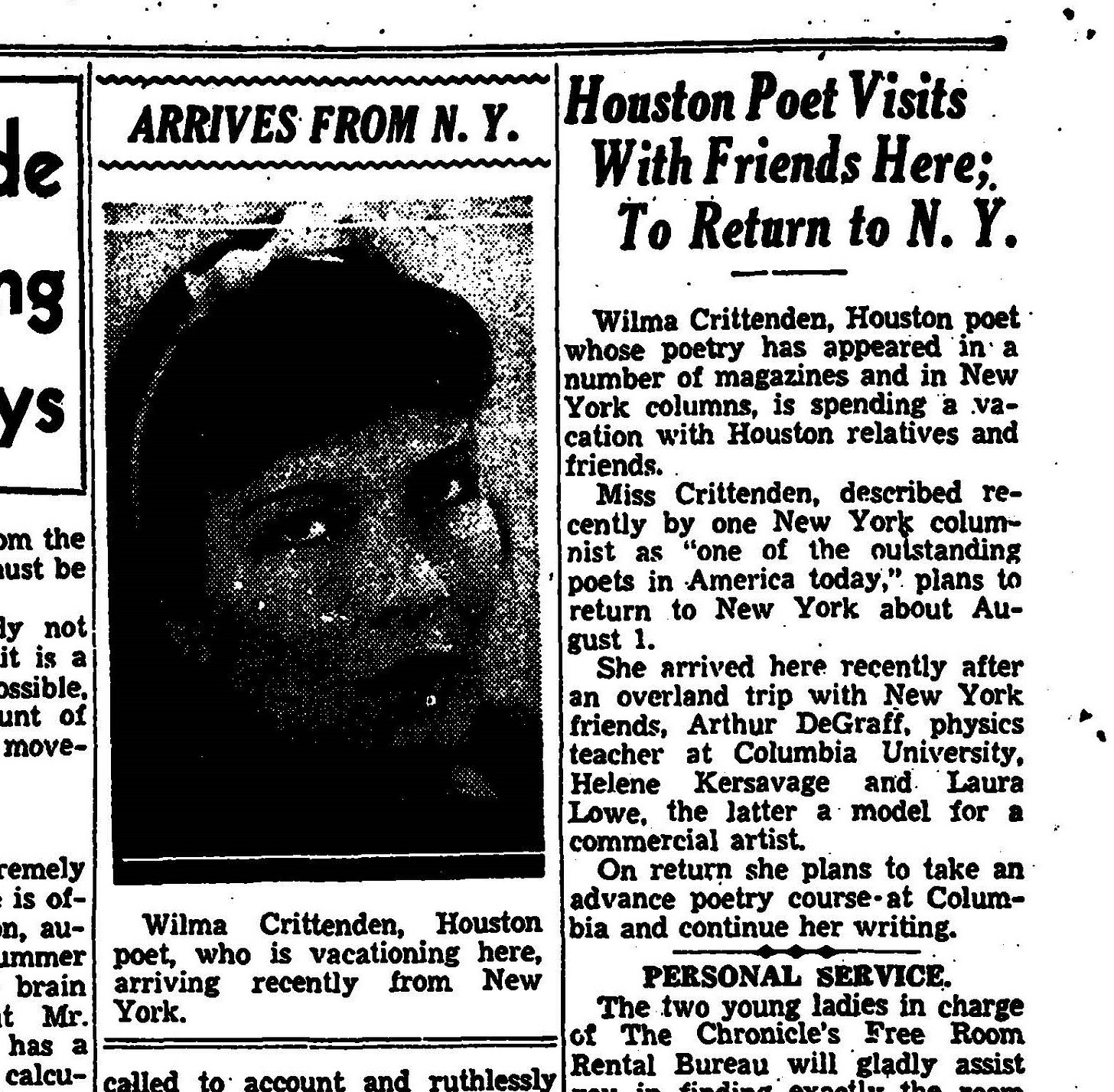

I sent my letter off to New York, to the last address I had for Wilma, and waited impatiently for the words of comfort that she’d be bound to send instantly in reply. Almost the last hope of comfort I still clung to.

Of course, as seems inevitable with such crushing affairs of the heart, I heard nothing from her, and my desolation seemed complete. If even Wilma, and her sharp, ironic, consoling words of comfort from a fellow love-loser failed me, what hope of comfort could I have?

And then, in July, I had a note from her, with a clipping from the Houston paper enclosed, a clipping I’d missed as I “sobbed” over my morning coffee:

“Just got yours. Forwarded hither and yon, as I made my most recent escape from New York (and Parker (tears)!), and at last awaiting me here in Houston when I arrived. Will be in touch as soon as trunks unpacked – and parents placated. Trust heart is mending – with ample “drinking, sleeping, weeping” – and will soon be ready to forge forward into LOVE again. Much Love (of that other, steadier kind), Wilma.”

Even in my desolation, I could not suppress a smile as I read her words. Yes, I had to admit, my heart was mending. By then, I thought of Russell only many times a day, not the constantly of those early days, weeks, months.

The heart was mending. I even considered making a journey with Grace John and Ruth Uhler, to Kansas City – at Grace’s invitation, remembering the fun of our summer in Santa Fe – where they would be painting assistants of Daniel MacMorris for his commission to paint the murals for the new Houston City Hall. I declined, afraid that I’d not be able to match their high spirits on what was clearly to be a trip for fun as well as work – a decision I regretted somewhat when I had a letter from Grace in which she described their adventures and mentioned that, “I have painted 12 life-sized buffalo heads and I’m beginning to feel like a big game hunter.” I’m sure she laughed as much as I that she painted buffalo heads for our City Hall, considering how rare the creatures were in Houston – one of the pictorial pitfalls of entrusting such a project to a painter from elsewhere – in this case, MacMorris from Missouri.

I regretted declining so much, in fact, that when McNeill suggested I join her on a motor journey to Chicago, where she would deliver her young “genius” student, Robert Preusser, in September, I readily accepted. Young Preusser would continue his art studies at the New Bauhaus, with László Moholy-Nagy, the Hungarian, German, now American, artist who had been forced by the Nazi ascendency in Germany to flee from the original Bauhaus, as had many others, some of whom had now found a more welcoming (and less threatening) atmosphere in America. Never mind that Mrs. Preusser, Robert’s not altogether congenial mother (in McNeill’s private opinion), would be among the party. She’d be returning to Houston by train, after she got Robert settled, and then McNeill and I – and the young artist, as he had time – could explore the art wonders of the “Second City,” which we laughingly boasted Houston would rival someday – a day none of us would live to see, of course!

That I’d heard Russell might have gone to Chicago would not be my reason for making the trip. But even confirmed love-hater that I had become, I could not deny, at least to myself, that the possibility of glimpsing him on a stroll down Michigan Avenue, or in a gallery of the Art Institute, was not an intriguing draw to say “Yes” to McNeill’s invitation. Hope, even crushed, endeavors to spring eternal.