Left Bank on the Bayou - Exhilarating Times

A Queer Houston Story of the 1930s

(Note: This is the next part of a serial novella. To catch up on earlier parts, look at the section titled Left Bank on the Bayou.)

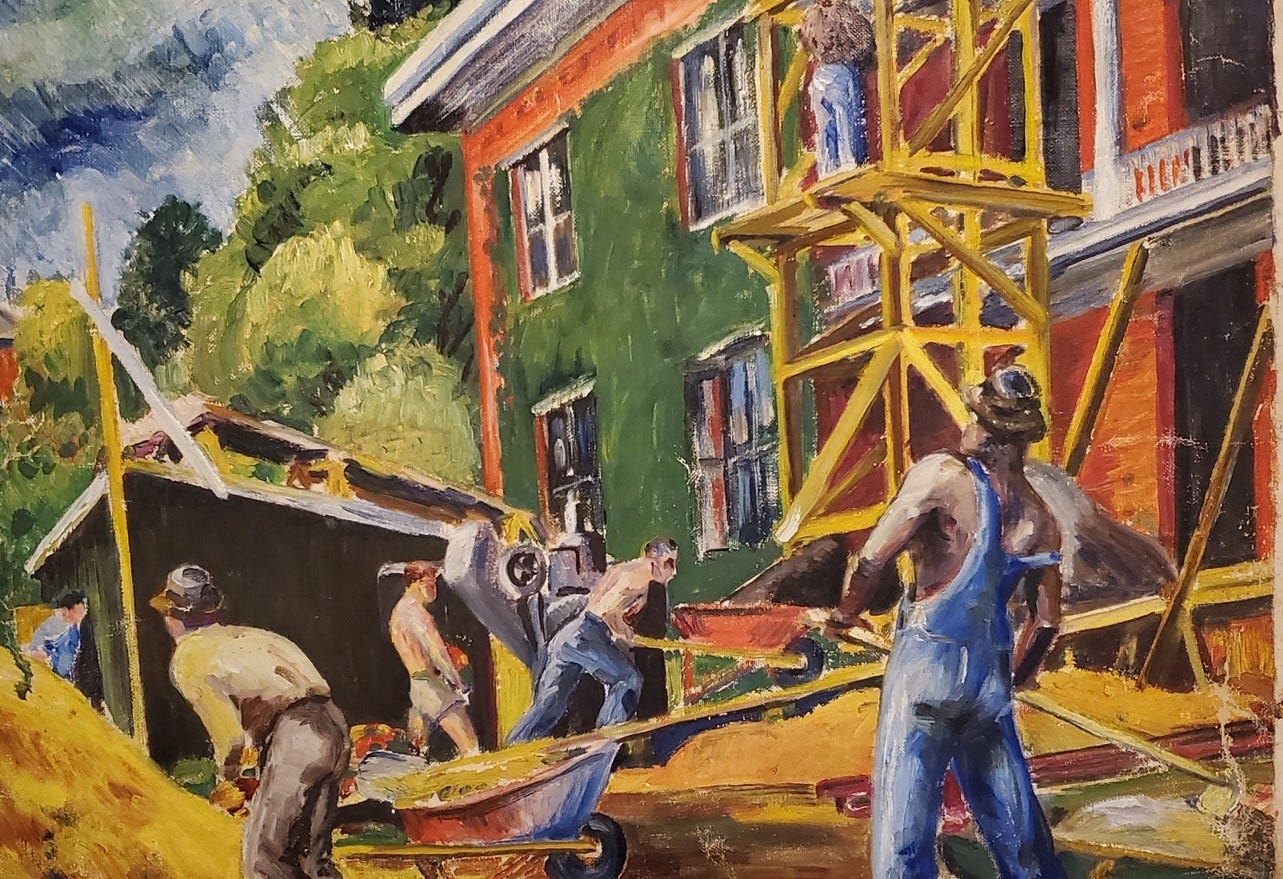

Those last weeks of 1938 and the early ones of 1939 were an exhilarating time. Russell had quickly made a place for himself in the Houston art world as though he’d been here always. In December he had an exhibition of his work, to glowing reviews: “The artist has the happy faculty of painting sunlight. … His water colors are strong in conception and free in brush strokes. His colors are clear and vivid rather than delicate.”

The reviewer might just as well have been describing Russell himself – happy, strong, free, clear, vivid. And sunlight. Certainly Russell was sunlight to me.

He showed mostly watercolors of architectural subjects, which sold well as house-portraits and seemed likely to make him a living as a successful artist in the city. Not that he need worry about warping his art toward making money. I would be there to help with that. But independent spirit that he was, he would not be beholden to anyone in that regard, not even one as devoted to him as I.

Along with the architectural works, he showed his watercolor portraits of children: “He has the knack of catching the sparkle and fleeting expression of Children.” Sparkle, fleeting expression: again, my Russell. He also showed his sketch of me at Seabrook. The reviewer, a friend, said nothing about it in print, though she had high praise for it in person; I still feared it might reveal too much.

In January the Ballet Russe returned to Houston, as they did every year for their winter respite from the frigid north. In honor of that always glorious spectacle, the balletomanes among us – that would, of course, be ALL of us – joined together to mount a group exhibition on the theme, The Dance. No one seemed quite to know who first proposed the subject, though privately I took pride in knowing the idea had been mine.

The show would open in Forrest’s South Main gallery on January 8, to take full advantage of the publicity surrounding the return of Ballet Russe the next week. And so from November, when local empresaria Edna Saunders announced the dates of the engagement, until the first week in January, all the artists of our little group whirled like Dervishes in a mad race to get their pictures (and marionettes, in the case of Jan) done in time, hearts racing faster than the races runners run. Mixing and mangling metaphors hardly seemed to matter at such a time.

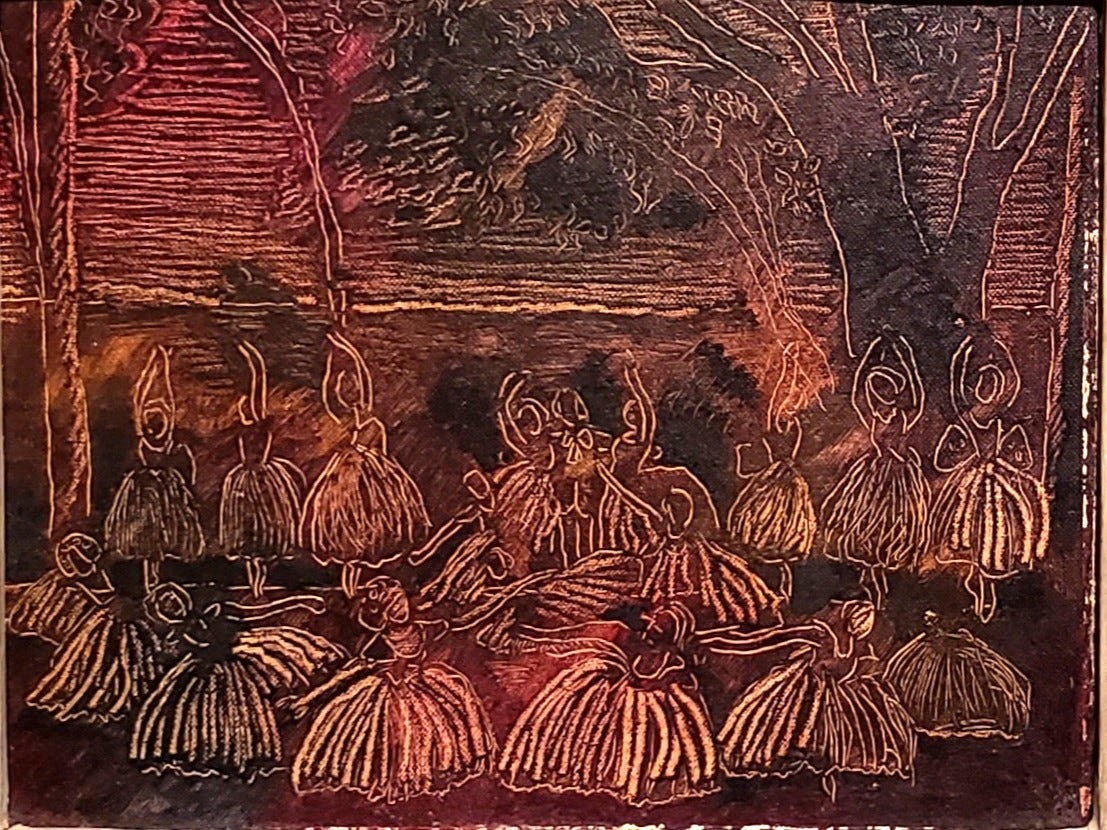

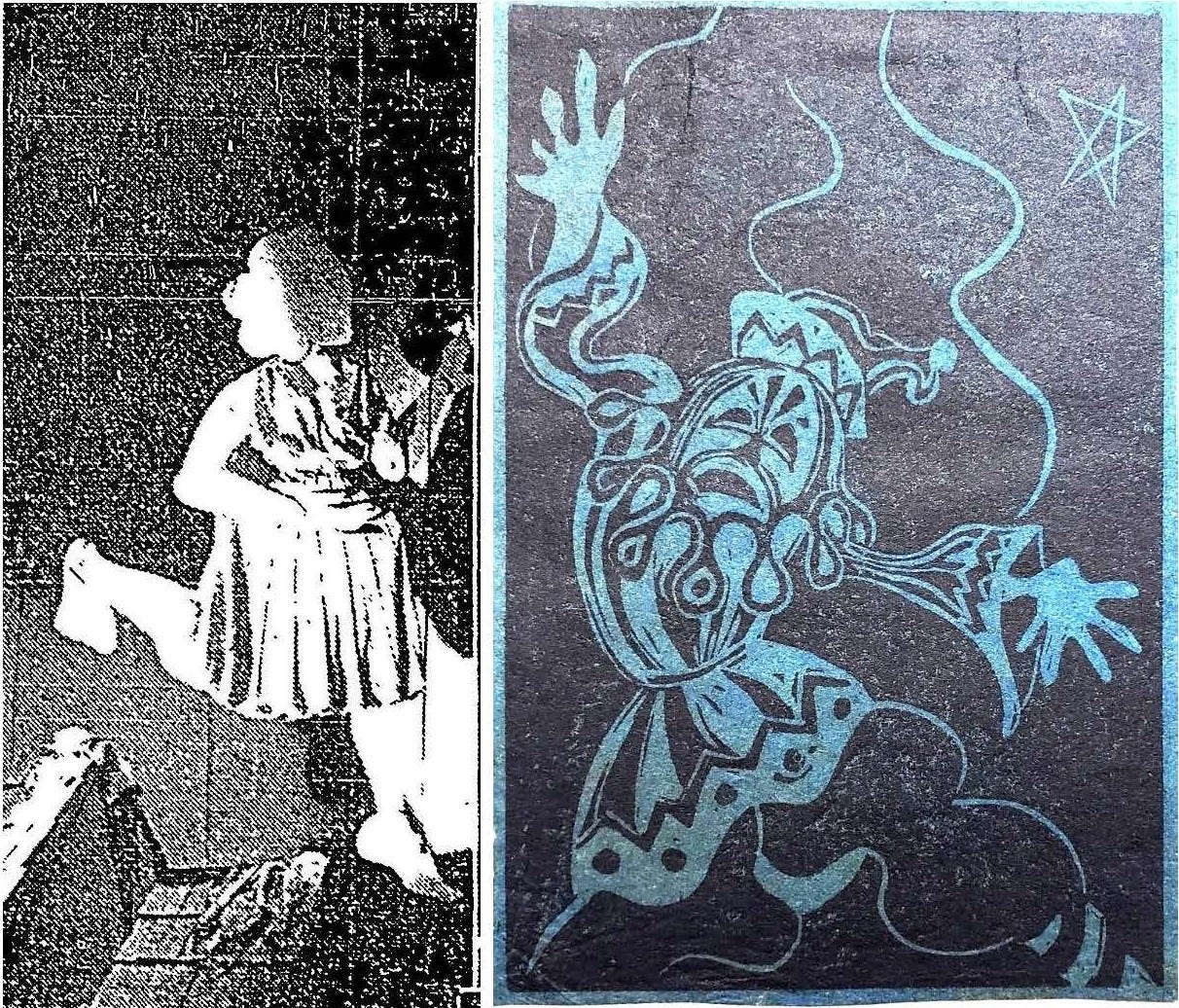

All agreed that it would be a triumph of a show, perhaps even rivaling the triumph of the Ballet Russe itself, with it’s company of 150, under the direction of the great Leonid Massine. Gene made delicate paintings of tutued ballerinas, and prints of a love-addled Petrushka, perfect compliment to Jan’s actual dancing puppets.

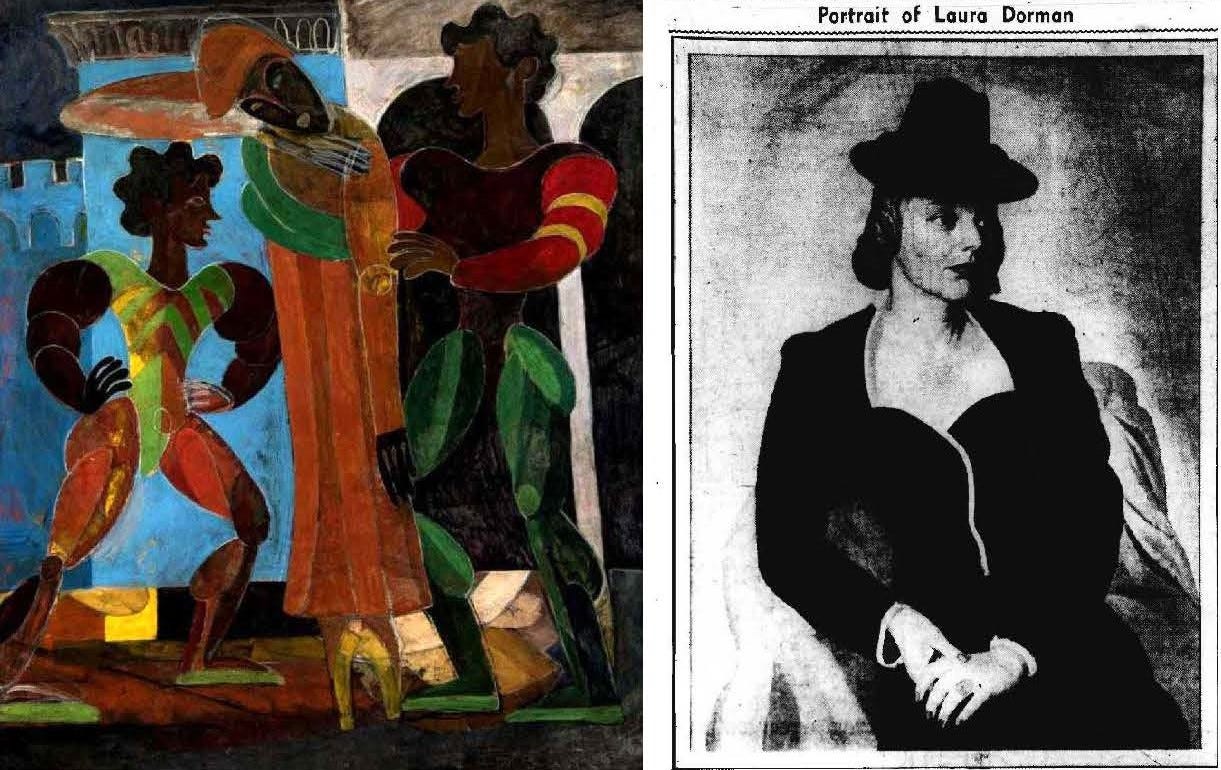

Cardy presented some of the bold designs he’d done for local recitals and concerts of Houston ballet masters (and teachers) Alexandre Kotchetovsky and Laura Dorman. He even included his recent portrait of Dorman as an added treat (and advertisement for a friend’s efforts, and his own skill as a painter of “distinctive” portraits).

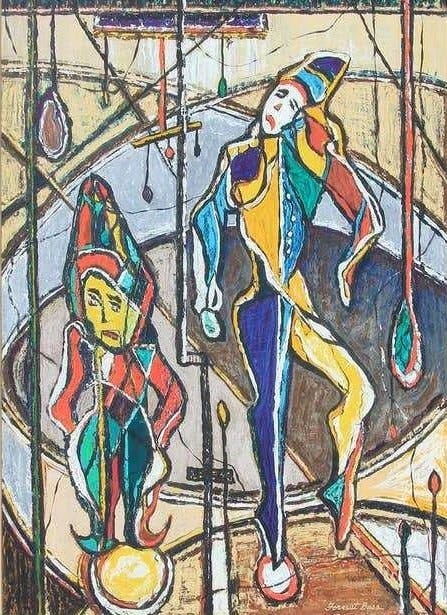

Even Forrest, perhaps the least dance dazzled of us all, found his contribution by way of a pair of dancing clowns. He did have a penchant for painting clowns – another of the slightly unnerving aspects of his mesmerizing personality.

For his part, Russell broadened the focus from the parochial confines of Houston and Russian/French ballet, to the world of dance – to the native dances of Mexico, the voodoo spectacles of Haiti, and the incredible, cross-dressing Méi Lánfāng of the Peking Opera, over whom “the girls went absolutely mad” according to reports from the Orient.

The Saturday night before we opened the door to the world, we had a little preview-party. To be sure it was a show that caused ripples spreading out across the city from the walls of Forrest’s stable gallery. Margo wondered if Houston might be ready for cross-dressing Chinese opera performers on the stage of her Community Players (and what the city fathers who funded it might think). Eddie engaged Jan on the spot to do marionettes for the windows at the Fashion Department Store for the spring; Lorin would work with her to carve them. Cardy got a commission for a portrait, even though one having nothing to do with dance. Gene cemented his place as one of the best artists in the city. And Forrest had a vision in which the clowns of his present painting transmogrified into three strokes against a solid deep blue field – which he knew meant something important, though he also knew he had not yet quite transformed enough himself to know exactly what.

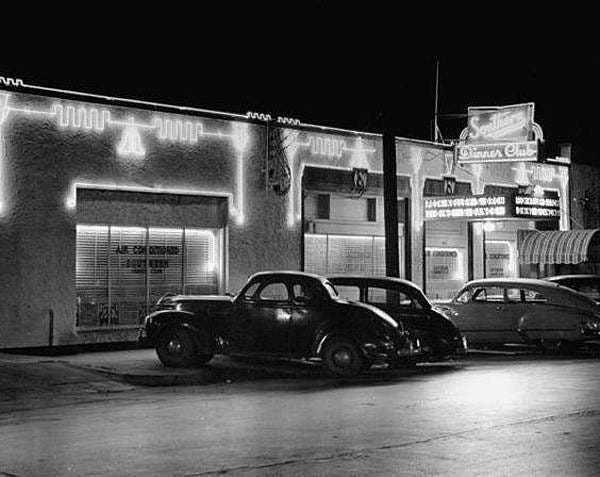

After the crowd thinned – which, in the art world of Houston meant, after the twenty or thirty avid art opening goers greeted each other and the artists, chatted a bit as they sipped that ubiquitous passable art-opening wine, glanced at the art, and then moved on to the other stops of the evening – when all but those of us closest to the artists and their art had gone, we all went over to the Southern Dinner Club on Gray, only a walk away, for some celebratory supper and maybe some dancing to the music of whichever orchestra would be playing that night: Eddie Oliver’s or Benny Bell’s or Peck Kelly’s – no telling which one it might be. If all went smoothly, Gene would soon be painting a mural there. But so often all did not go smoothly with such commissions.

Oh, how I longed to be dancing with Russell, and he with me, I thought. Not possible, of course, and so not even worth worrying about. That had hardly been more than a dream even in Paris and New York, so not even to be thought of here in Houston, in the south – though maybe in New Orleans at Mardi Gras, in darkest corners. But otherwise, impossible. We all knew it and we all accepted it as the way it had to be. But the needling wish persisted that it might, sometime, somewhere, be different.

That night Russell decided to stay at his studio. I didn’t quiz him as to why. Some things you know instinctively not to do; or you know them from the sort of visceral learning that comes with touching a hot stove for the first time. He had no bed in his studio, but he’d moved a sofa in, for naps, which could do, perhaps, for longer sleeps. Or perhaps he felt inspired, after the triumph of the show, and planned to paint all night. Whatever the reason, what must be must be, and must be accepted. Explanation, and often understanding, did not enter in.

Certainly I did not understand, but I sensed that something had changed. I couldn’t know what – or couldn’t let myself know that I knew, if I did – too little courage for that. But something. When the party at Southern Dinner Club broke up – not a late party, since we all were exhausted from getting the show done (though exhilarated too) – Russell and I walked back in the direction of his studio. At the tram stop on Travis, we stopped and he said Goodnight and kissed me on the cheek: a bold gesture, so public on the street, even at night. Then he turned and continued toward Fannin Street.

As I watched him walk away, the tears welled into my eyes and began their usual course down my cheeks. How many times had this happened since that first time when I realized that Clem would not be coming back to me in Paris? Too many for the tears to be flowing again. I should have learned by now - long before now - how to keep eyes dry, heart stout. If not by now, when would I learn it?

It always, always would be tears, it seemed, in the end.

I watched him until he’d turned into the street that would take him to his studio – or wherever he’d be that night – away from me. I turned too, and walked. I’d walk back to my house; it wasn’t so far, the evening was pleasant, and I needed solitude and time. Time for what I wasn’t sure. Not understanding. Not even acceptance yet. But time. I walked toward the house almost in a daze.

For a little longer I’d still think of it as our house, but that would fade – with time.

Great description of Forrest Bess moving toward visionary painting & transforming his body too.

Love all the history and photos/paintings, ending a little sad and interesting. 🥺