I See Where This is Heading

And It Doesn’t Thrill Me

I see where this is heading, and it doesn’t thrill me. Nope, doesn’t please me at all. Because it’s heading toward death – no use trying to sugarcoat it – moment by moment, year by year. And the only control I have over it is maybe with getting there sooner.

No one asked me if I approved, even though it’s my life (that is, the end of it), which, for me at least, is a big deal.

For the record: I DON’T. Approve, that is.

But clearly those “powers that be,” whoever or whatever they may be, don’t give a damn how I feel about it.

Yes, I know it’s the human condition, and we all face it. But do you really believe that knowledge makes any of it better? At 3 AM, on a cold winter night when the Texas power grid might fail at any moment – or so might my heart – or whatever it is that keeps one’s head from exploding as such thoughts race through it like the charging bulls at Pamplona? (I realize that there must be a better analogy than that, but I sure as hell don’t have time to waste on such quibbles now!)

Night is the hardest time, because there’s not a lot to divert those thoughts. Especially now that sex obsession has petered away to “not with a bang but a whimper.” (You know I’m not talking about you here, but most.)

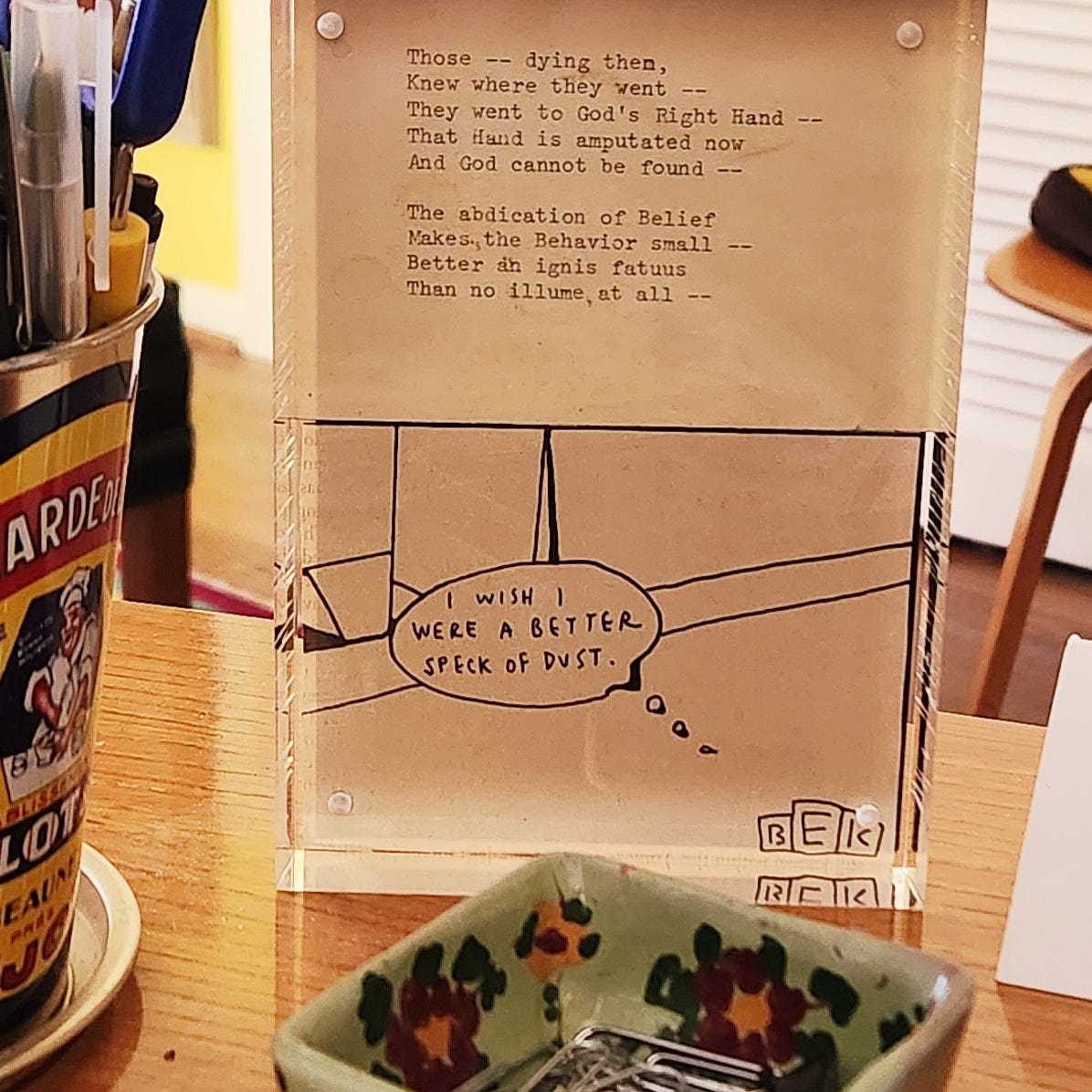

There’s an Emily Dickinson poem which has always intrigued me (another word for haunted, in this case), and which I have rigged up in a frame, along with an equally “intriguing” New Yorker cartoon. I keep them before me on my desk:

Those – dying then,

Knew where they went –

They went to God’s Right Hand –

That Hand is amputated now

And God cannot be found –

The abdication of Belief

Makes the Behavior small –

Better an ignis fatuus

Than no illume, at all –

Indeed, Emily, as usual, has put her finger right on the pulse of life for me – or stuck it in my eye, so that I can’t possibly look away. Ignis fatuus: I had to look it up. But whatever it was, I wanted me one, if it would make things better, as she said.

Especially so after I’d cut off God’s right hand by leaving the certainty of the fundamentalist Christian religion of my youth. There was no uncertainty then: We were all damnable sinners, worthy only of an agonizing, burning eternity in Hell, and certainly heading there – but for God’s grace – grace available for all – but with conditions.

As the years of my youth passed, and the innocence of childhood (does such an ignis fatuus really exist?) gave way to the hazard field of adolescence, I came to realize that I did not meet the conditions, especially in one hulking particular – the one excluding Sodomites (as they/we were called then, when not being called fags, pansies, queens, fairies, queers, or a number of other equally endearing – in some cases, graphically explicit – names). Of course, I was not called such names – to my face – because I became a master at disguising that fundamental element of my self (we often learn to do that early and well ; one reason so many of us are good actors), and I’m sure no one ever knew back then. (This is, of course, a fatuous comment. I’m sure that many knew – maybe everyone, at some level – though many, including me, were not yet ready to acknowledge it.)

And so I seemed to have no choice but to amputate that particular God’s right hand. It was them or me, and I chose me – in retrospect perhaps a choice of dubious wisdom. Because once I had journeyed out of certainty, there was no getting it back. “Better an ignis fatuus,” she says, “than no illume at all.” But what comfort can there be in an ignis fatuus when you know that’s what it is? You can pretend, but you can’t believe – and that’s just another form of acting. Once you’ve known the “truth,” had certainty, and left it, there can be no other certainty, because no other “truth” can be absolute. And it’s the squishy, uncertain areas that cause the angst.

Even if I’d known all this back then, when the amputation happened, would I have done differently? Probably not. I was young and foolish, as they say, with a whole life ahead of me (what a instant that seems now) to get certainty back, or learn to live without it. As it has turned out, neither happened. Back then it was still possible to think that death applied only to others, including that “other” I would become in the 60 or 70 years it would take for me to get old – the 60 or 70 years that are now long past.

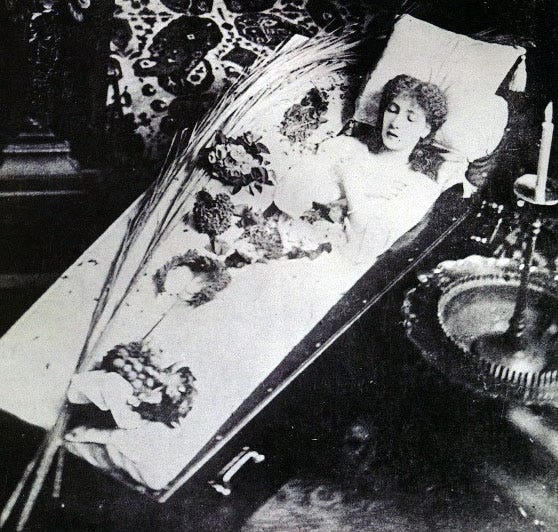

But even if I’d decided the other way, stayed with certainty, I’d have had a life of even more hiding (shall we call it acting?) than the one I’ve had. What kind of life would that have been, always acting, always lying? And still I’d have known the truth. Because when it comes down to it, God and I are the only two who can’t be deceived about me, even by a Bernhardt-quality performance. I now rather suspect that the coffin she’s said to have slept in wasn’t just a theatrical prop, but an effort to get ready for the future, and somehow somewhat comfortable with it, in the present. I’m not quite there yet myself, but I’ve measured the bedroom to see if there’s coffin space.

So here I am, back at the human condition, at 3 AM, with the shaky power grid and not even an ignis fatuus to warm me. I know that death can’t be far away – no delusions about that now – and then … the great uncertainty. And no one ever asked if I approved. How unfair is that? But I guess that’s not really the biggest issue now, is it?