Forrest Bess "Messed Up Once"

An Earlier Houston Artist Comes Out To Friends

Forrest Bess (1911-1977) is the most famous Texas artist from earlier times. Some of his paintings, the so-called visionary ones, sell for hundreds of thousands of $s. In recent years there have been exhibitions of his work in London, England, in Germany, at the Whitney Museum in New York, The Menil Collection in Houston and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. He’s world renowned.

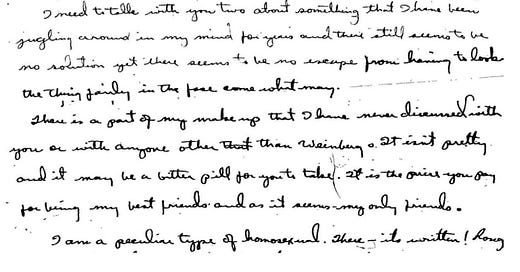

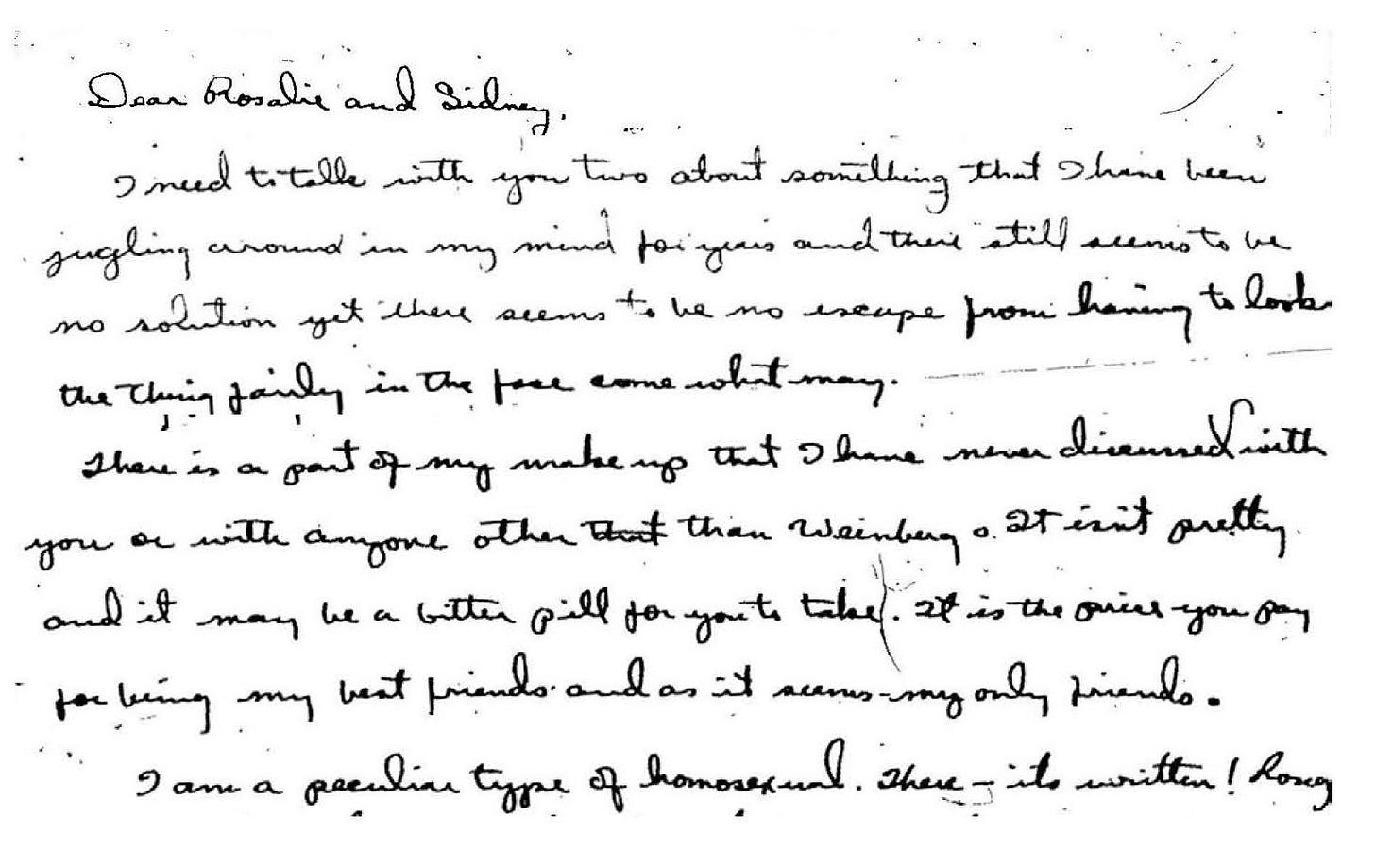

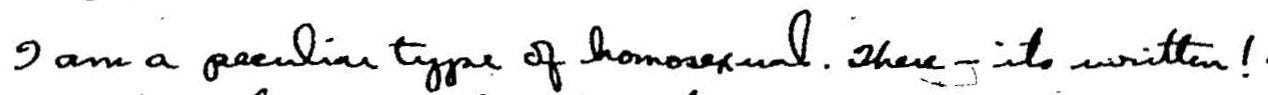

He was also – and these are his words, not mine – “a peculiar kind of homosexual.” That’s the way he described himself in a 1950 coming-out letter to friends. He didn’t go into what exactly he meant by “peculiar,” but he did allow as how even for those close friends it might be a “bitter pill.” But that was the price of friendship, and if it was hard for them to take in, it had been even harder for him to live with. “There – it’s written!” he said, and once written, and mailed, it had to be faced, no matter how hard.

In his letter he told how he’d left his Bay City, Texas, hometown, back in 1938, when someone he’d confided in, someone he thought he could trust, blabbed his “peculiar” secret all over town. After that even his Bay City friends couldn’t have anything to do with him, for fear they’d be tarred themselves with his homosexual taint.

So he moved to Houston and found “protection in numbers with people I thought were my own kind.” He did find some of his own kind among the artsy Cherry-McNeill Group who populated Houston’s mid-town at the time, and all went well at first. He renovated an old stable into a studio/gallery where he showed his own art, along with that of some of his new Houston friends, who included life partners Gene Charlton and Carden Bailey, among others. He joined them in putting on exhibitions about art and dance, and art and abstraction.

But after a while he found that even in Houston things weren’t working out: “I was too ‘butch’ – rough for them – I was an oddity and I didn’t fit – I wasn’t effeminate enough.” This from a guy who, later on, did a bit of self-surgery so he’d be both male and female, and not just in a figurative way! No surprise that one scholar recently cast him as a harbinger of today’s more gender fluid age.

After a stint back in Bay City, he joined the military when World War II came along, and he did well there as a soldier: “channeled the sexual feeling – made an officer – citations and commendations.” But then, as he told his friends, he “messed up once” after a night of too much drinking and too much excitement. He wound up in the hospital with a caved in skull: “lead pipe and facing court-martial and disgrace.” All that saved him from that disgrace was the revelation that the guy who gay-bashed him had tried the same blackmail and robbery trick on other officers three time before. It was after the bashing that he concentrated on painting the paintings that have made him famous, working from visions he saw on the insides of his eyelids, so he said.

After the war, he moved back to Bay City, vowing that he would never again give anyone the chance to use “lead pipe – heels, or blackmail” against him for being homosexual. He wouldn’t declare to the world that he was “queer,” but he wouldn’t deny it either if anyone asked. He took up a solitary life in a bait camp/studio he built at Chinquapin – solitary, but not the hermit life that’s become part of his myth, since visitors were always stopping by, so many it’s hard to see how he ever got any painting done. He made trips to Houston, and even New York, where his paintings caused a stir every time prominent gallerist, Betty Parsons, showed them in her gallery.

But at home in Bay City there was “no sex” because he didn’t want to embarrass his father, who “couldn’t understand at all.” By the time of his 1950 letter, he related that “there has been no sex here for me for the last three years.” Sounds a little bleak, maybe, but there was a silver lining for his art: “I have knocked myself out working too hard many times. It is the only way release can be obtained.”

And now he’s world famous, so maybe even sublimation has it’s up side!

At about the same time that Bess wrote his coming-out letter, he painted the male figure study on the left above, dated 1953. The painting may even be a self-portrait - have a look at the photo of Bess in his studio and see what you think. But whether a self-portrait or not, he likely found his inspiration in the STANDING YOUTH of 1913, by the German sculptor, Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881-1919). Bess tells us in another letter that he had a postcard image of the YOUTH tacked to his studio wall.

I am surprised at his receiving many visitors when he was back in Bay City. Nice to know a little more about him.