This year, finally, I made it to one of my Earlier Houston Art History bucket-list destinations. In May, I finally went to Giverny. You know, that little town not far down the Seine from Paris, where that French artist – what is his name? – lived, painted and gardened to the delight of an enthralled 20th/21st Century art groupie world.

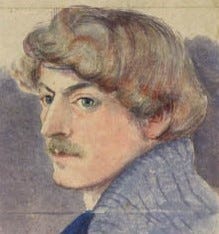

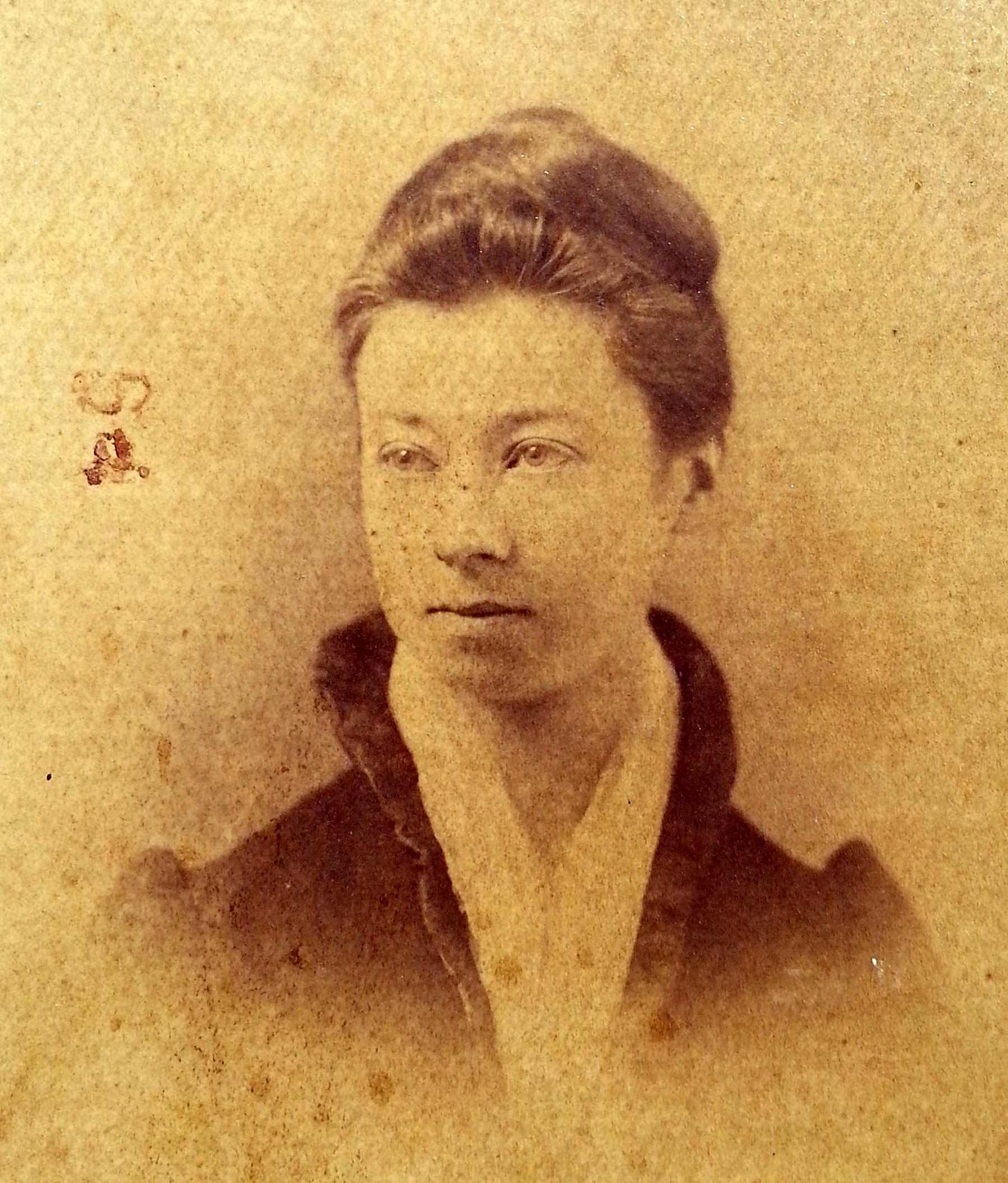

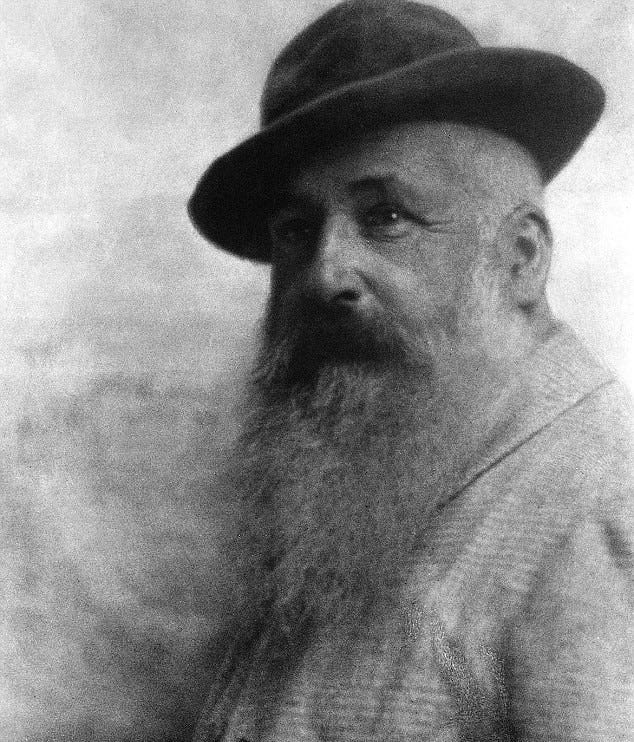

But I didn’t go because of what’s his name. I went for the reason that every real devotee of Earlier Houston Art History should go there: In 1888/89, our own Emma Richardson Cherry (1859-1954) “may well have been the first woman artist” to paint there! So says eminent American Art Historian, William Gerdts, in his book, Monet’s Giverny: An Impressionist Colony (Abbeville Press, 1993, p.33). Oh, yes, Monet. That’s the name of that French guy.

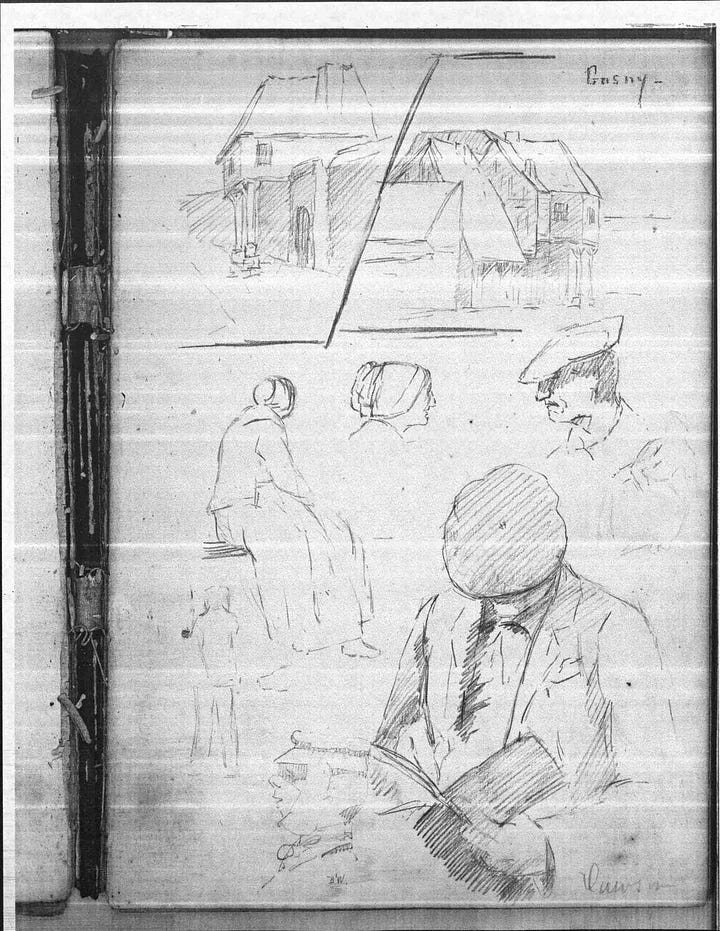

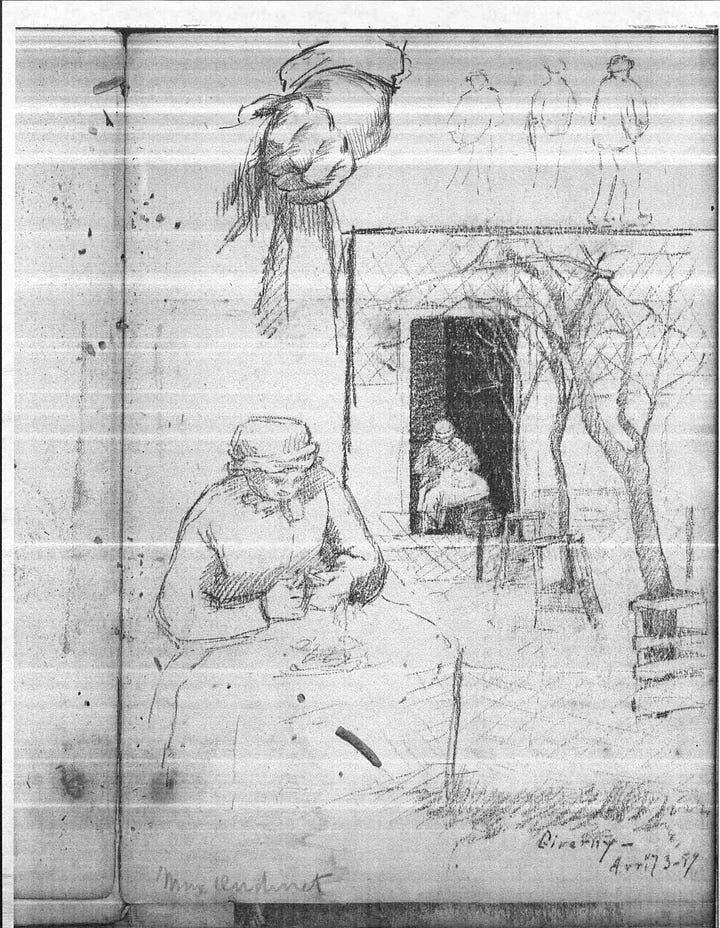

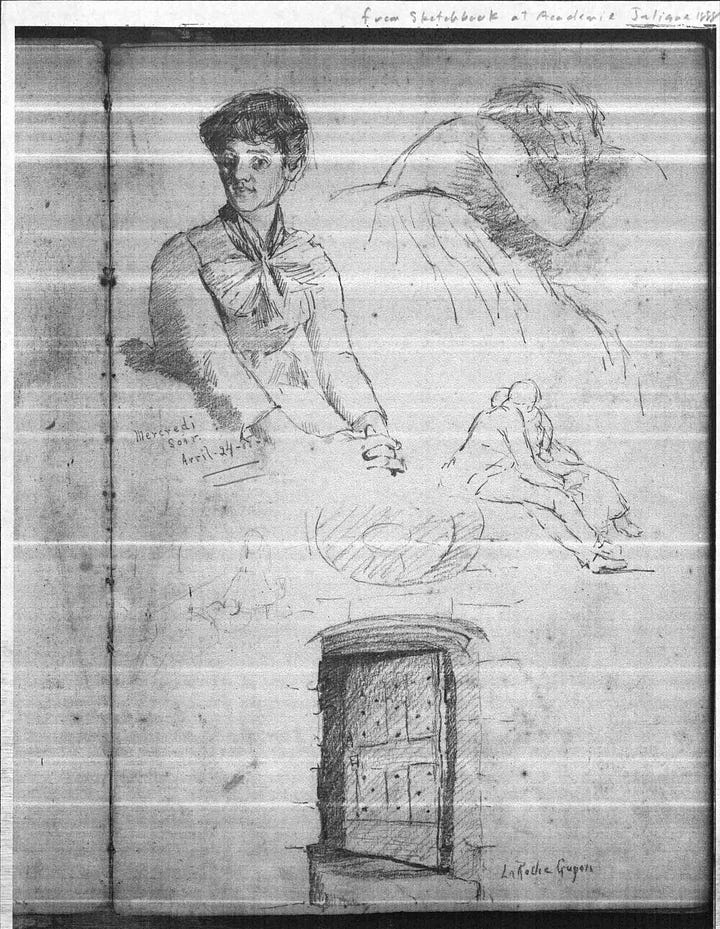

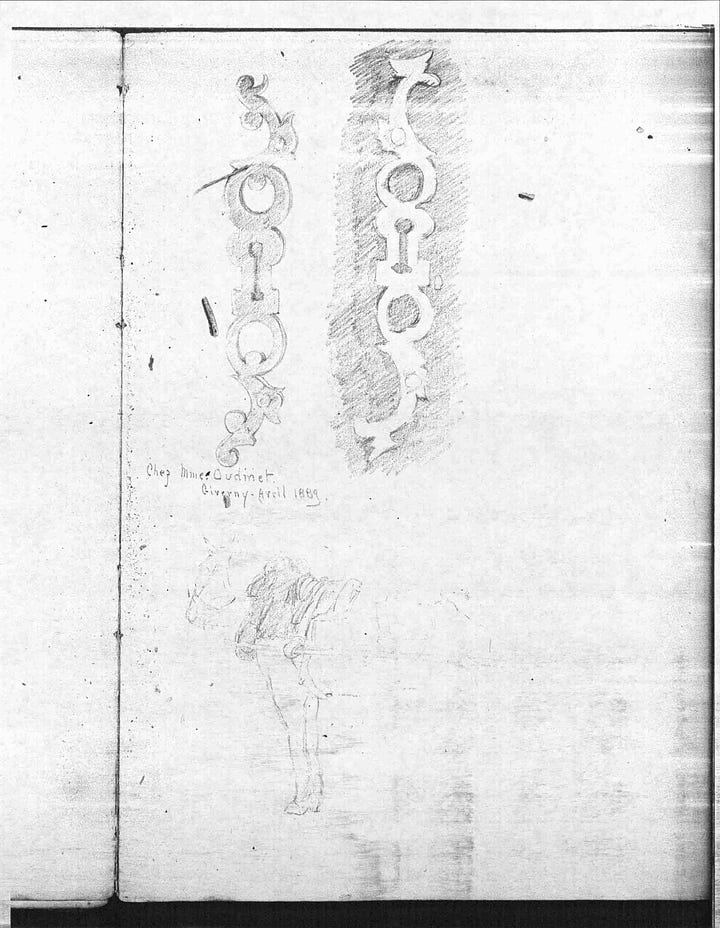

Whether or not the first, Cherry was certainly one of the earliest woman artists to visit the fledgling art colony, and she painted at least half a dozen paintings and filled pages and pages of her sketchbooks during her two visit there, in October 1888 and early spring 1889. She took the short train trip from Paris to visit her childhood friend, and traveling companion, Mary Hoyt Sellar (1864-1952), and Mary’s new husband, the English (later Texas) painter, Dawson Dawson-Watson (1864-1939).

The two young women had arrived in France only in January, 1888, and by May, Mary was already Mrs. Dawson-Watson. You might call it a whirlwind romance. And since Dawson lived in Giverny, one of the very early artists to go there to paint, that’s where the couple settled. Cherry was a newlywed herself, having married Dillin Brook Cherry in Kansas City only two months before leaving on an already-planned, two-years of art study in Paris.

And so I’d been remiss in letting 20 years of research into Cherry’s life and career – and at least that many trips to France – slip by before venturing the short way from Paris to Giverny. But on a splendid April day this spring I made my amends. Truth be told, I even went to see Monet’s garden and house, which were lovely, if a little crowded.

But then, after that obligatory pilgrimage, I slipped away from the crowds, and explored the nearly deserted streets of the village a few blocks away – in search of the sites Cherry painted (and photographed) 135 years ago.

And, Eureka!, I found the sites I’d come to see – some of them anyway, as certainly as one can be after so many decades of change, even in a tiny village where nothing much has changed – except that it’s become one of the most visited tourist destinations in the world.

A few hundred yards along the main street of Giverny, just across from the Ancien Hôtel Baudy, where so many of the early artists stayed on their excursions to the town, I stopped at a shop and showed the shopkeeper a photo of one of Cherry’s watercolors, asking, in my painful (but serviceable, it appears) French if she recognized the spot. And I explained why I hoped to find it, emphasizing Cherry’s early stays in Giverny.

“Mais, oui,” she said with a beaming smile, and she took me to the door of her shop and pointed back down the street we’d walked along – apparently we’d gone right by our prize. “C'est là-bas. Certainement.” And it certainly was.

And how appropriate that the street we were seeking is now named rue Blanche Hoschede Monet – after another woman artist, who may, in fact, have been the first woman to paint at Giverny, since she was Monet’s daughter-in-law (and step-daughter), as well as his assistant from the early 1880s. If Cherry must defer as “first,” then what a fitting predecessor to defer to.

A little further along, we spotted another possible Cherry scene – a field stretching away from the rue toward distant houses, which may have been in her view as she painted her exquisite, tiny watercolor Rainy Afternoon, Giverny, probably in the spring of 1889. We saw the scene on a bright sunny day, not a rainy one, so our identification may be questionable. But I think I’ll go on believing it’s the spot.

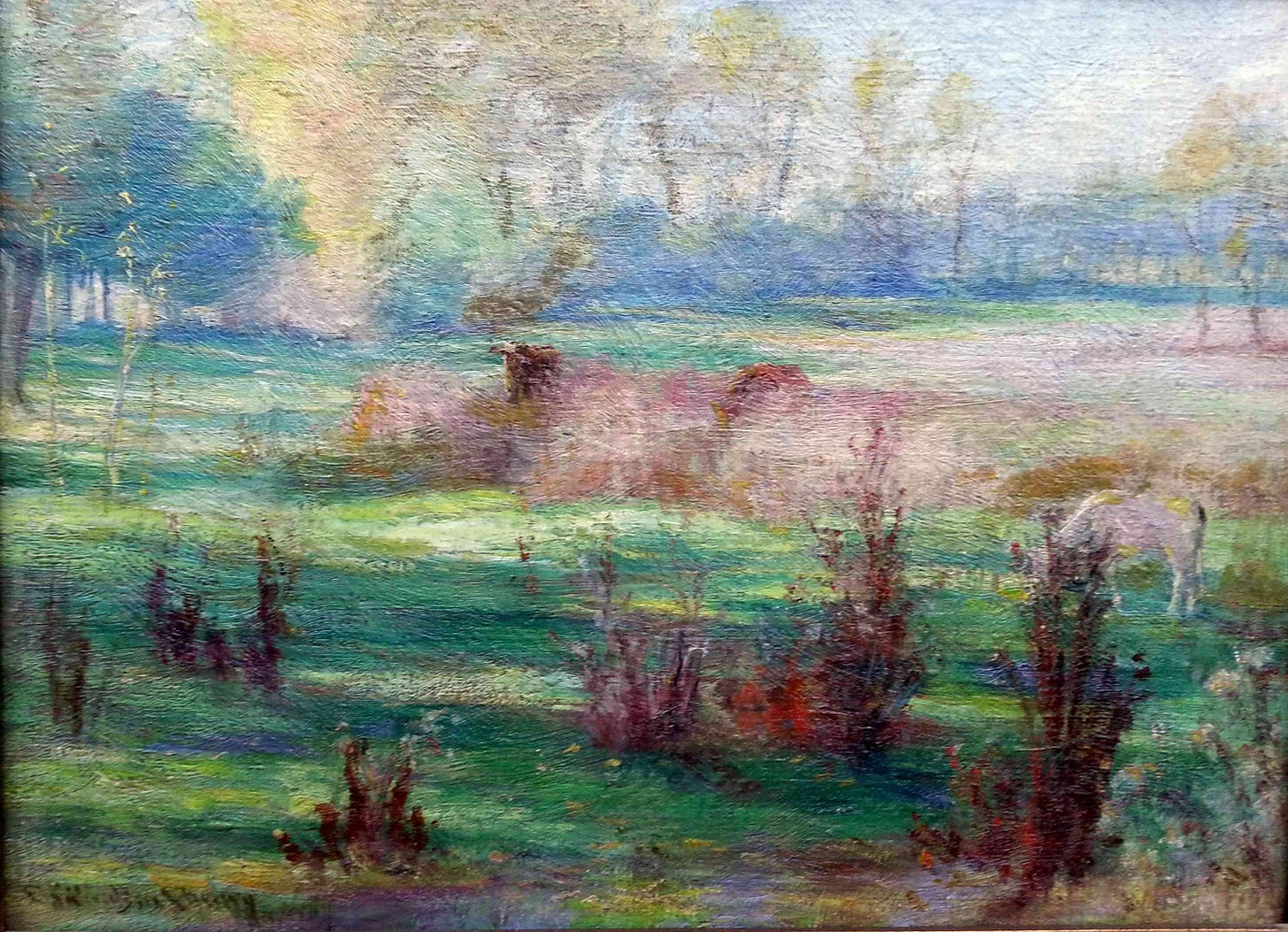

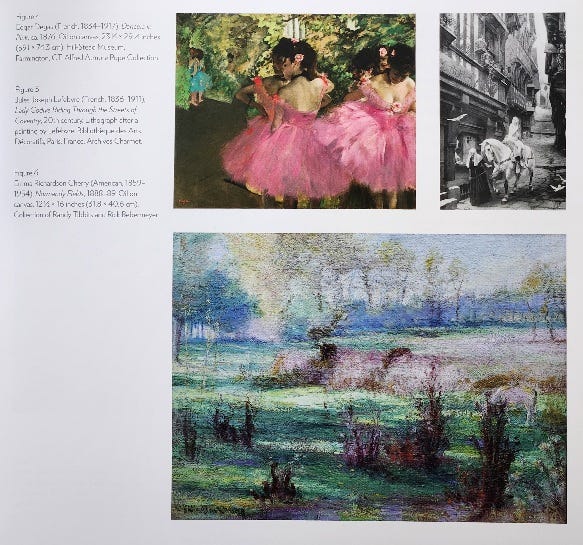

The cows had moved by the time we arrived in Giverny, so we weren’t able to be sure which field Cherry chose for her painting, Normandie Fields, ca.1888/89, but the painting itself has been keeping good company in recent times, appearing on the same page with works by Jules Lefebvre, one of Cherry’s teachers in Paris, and Edgar Degas, in the catalog of the recent exhibition, America’s Impressionism: Echoes of a Revolution (Yale University Press, 2020).

Since her Giverny sketches are less finished, and more personal, identifying locations that may embody them was less likely. Still, as I walked the few streets in the tiny village, I knew that I might be looking at what Cherry had looked at all those years ago. And I thought that maybe – just maybe – even the aloof, august Monet, walking these same streets, might have shot a sidelong glance at the American woman painting or sketching there along the way, and might have thought (though he never would have said, of course), “Pas mal,” and given a little smile before passing on.

[To be continued]

Lovely, Randy! Makes me wish to be there.

Wonderous trip to discover what she discovered. I’m glad the village is still tiny and untrammeled to some extent. Beautiful, thank you.