I Speak It - For Those Who Dared Not

A St. Louis story of the 1970s

I became part of his story one sultry summer Saturday in Saint Louis, fifty years ago, and he became part of mine. I was a young gay boy lunging into life without a guidebook. He was a man caught between his circumstances and his essential nature: wife and children, social register listing, church deacon dignity on one side; and on the other, all the beautiful (and even not so beautiful) men he’d always desired, even long before he would, or could, acknowledge to himself that he desired them. As long as he kept the two in separate worlds, there seemed to be no problem living alternately in one and then the other. For some time, this never-the-twain-shall-meet approach may have succeeded. But what a dull story this would be if he’d been able to keep the two apart forever. It was not to be.

That Saturday I’d been sunning – another word for cruising while wearing as little as legally possible in a public place – at the Gay Beach in Forest Park – not really a beach, though that’s how I thought of the vast grassy field tilting down to a man-made lake on the eastern side of the park. I, and scores of other gay boys who lived in what was then – this was the 1970s – the gay ghetto of St. Louis, officially, the Central West End, went there on summer Saturdays after breakfast at the Majestic Café, when Friday nights had not climaxed in a trick, or at least not one alluring enough to keep around through breakfast. Or maybe not enough allured to stay: another possibility. I bicycled there because I had no car, and even more, because peddling showed assets off to good advantage

Eggs, sunny side up, bacon, crisp, home fries, wheat toast – my usual – was all I’d scored at the Majestic that morning. There was always the hope of scoring one of the other gay ghetto boys also suffering from hangover and Friday night trick disappointment – it was said to have happened – though that may have been a gay urban myth. I’d never managed it in years of trying, nor had any of my friends. Still, there was the hope of a chance. But again that morning I didn’t, so after another refill of coffee and one more longing look at yet another firm, rounded young male butt walking out the door without me, I decided I needed some sun.

I’d actually managed to trick in the park – not often, only once or twice, but it could happen again, why not? So I peddled over there – five minutes away – and laid my bike on the grass and rolled out my towel, and slowly, sluttily slipped off my cut-offs – I already had my scarlet Speedo on underneath. I slathered sunscreen onto all the spots I could reach. I spread it suggestively in case someone might come over and offer help with the behind spots I couldn’t reach. But no one did.

I’d been lying there half an hour, turning from time to time in the hot sun, like roasting meat on a spit, so that I’d burn evenly – but even more, so that any who looked my way could get a view of both my basket and my buns – all the goods on offer – as they made decisions about next moves.

I’d given sidelong glances to some of the other boys – even some of the ones I’d been seeing already for years, there in the park, or in the bars, or the baths, or street-cruising on Euclid or McPherson. I looked at a couple I’d pretty hotly wanted but never had, with lingering come-hither stares – which got me nowhere. I’d about accepted that it would only be sun in the park that day, just as it had only been eggs at the Majestic – not the most desirable outcome, but at least I’d make a dent on my summer tan.

Then he pulled up to the curb and got out of his sporty little car – maybe a Jag – cool enough to make car-lovers (though I was not one) swoon. He, on the other hand, might be worth a swoon, even though a fish out of water on our gay beach: a preppy-looking guy, far beyond preppy age, in linen summer suit, pale pink shirt, baby blue bow tie, Panama hat, and shoes of a soft-looking tan leather, practical only for smooth pavement in dry weather. He might have been coming from a country club wedding, or a race-day julep brunch, or a lesser Tennessee Williams play that had tried and failed on Broadway. Some of the Williams plays that had succeeded were written, or at least started, just the other side of that very park, they said, so maybe that was the likeliest explanation for his origin.

He strolled across the grass, looking at this boy-roast and that bit of basting beef, and passing on. Until he got to me. What it was that made me the one he stopped for, I didn’t, and still don’t, know. Maybe I’d reached just the right degree of doneness for him. Whatever, he stopped and looked down at me and said, “Hello.”

I looked up at him. The dazzling sun haloed his head – though, as I learned later on, it was no saint’s halo. I shaded my eyes so I could look without searing my retinas. And I said back, “Hello.”

Long past the preppy age indeed. Fifty at least; maybe older. The beginnings of crows feet at his eyes, creases both sides of his mouth, mostly – but not entirely – masked by a robust mustache. At close range an unmissable hint of paunch at his midriff which hadn’t been glaring at a distance, with the bright sun and the off-white linen. Not one of the young gay boys, for sure, or even one from the just-previous generation, returning to the scene of recently faded youthful glory. No, not a boy, a man, and a man with years on him.

Even so, not a study in devastation – the sort that years, and experiences, and maybe drinks and drugs, can sometimes transform a man of his age into, no matter how alluring he might have been in an earlier stage. He still had allure – of a sort that I, in my inexperience, had never perceived in any man before.

“I’m an artist,” he said. “Would you model for me?

I’d heard, and used, pick-up lines myself, but I’d never heard and for sure never used that one. But that it was a pick-up line I had no doubt; what else could it be? There was no reason he’d want me as model, in preference to so many others also displaying as blatantly across the grass. I was wary; but vanity and inexperience insured that I was flattered too. Why wouldn’t he pick me? I had allure myself. Why not?

“I guess so. What for?” I asked

“Photos first, then we’ll see,” he said. “Here’s my card. Come to my studio at 2, if that works. If not, we can find another time.”

I took the card, and lowered my eyes from him and the sun to read it. I knew the street; not far. “It works,” I said. “What should I bring?”

“Nothing. Come as you are. They’ll be nude photos. And drawings.” Perhaps he anticipated hesitation from me. “I’ll pay by the hour.”

It sounded shockingly (and enticingly) like a proposition. I wondered if he might be an entrapping vice-squad cop; rumors said they preyed on naïve gay boys in the park. Worldly-wise friends admonished me to be careful. But this man? That was too improbable. And so I told him I’d be there.

“Good,” he said. He walked back across the grass to his sporty car. I watched him drive away, then looked at the card again. There it was, still in my hand; it hadn’t disappeared with his departure, as I half thought it might. I glanced around at the other gay boys splayed out across the grass. I let myself believe they now regretted their indifference back when I could still have been theirs, for pleasure, for the day. No chance of that now. Now I’d be otherwise engaged.

II

He opened the door after I’d rung the bell a couple of times, and then knocked, because there’d been such a long delay I assumed the bell was dead, even though I thought I’d heard it. He didn’t say anything to indicate one way or the other if he’d kept me waiting on purpose. I couldn’t think of any reason why he would, so I assumed he hadn’t. But it started things off on an awkward note.

He had me lean my bike against the papered wall just inside the door, and then led me down the hall to the studio. It was large, with a high ceiling and expansive windows starting halfway up, clearly built as a studio, and not converted from something else. And it had been a studio for years, maybe decades, maybe even from a time before he’d taken up his own artistic residence there.

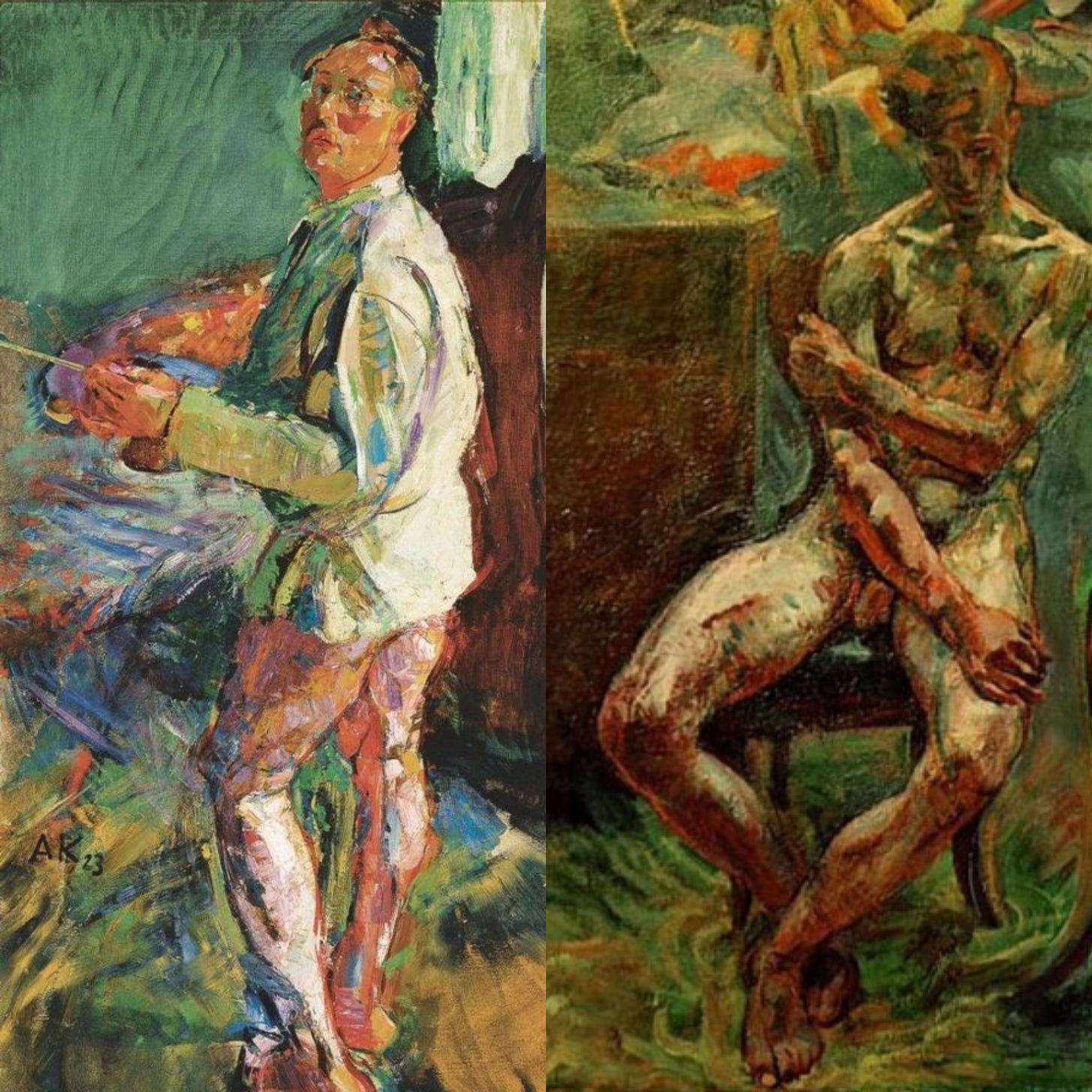

If it was his work that crowded the room, then he was a sculptor. I’d assumed “painter,” though for no more reason than my own preconception about what a person meant when he introduced himself as an “artist.” Pieces in clay and plaster and marble, and even bronze, on tables and lazy Susans, and the biggest ones on the floor. Sculpting chisels lay beside several, so it wasn’t clear which pieces were current work and which from long ago. A few abstract forms, a few portrait busts, but many more fawns and flowers and groups of frolicking children – sculptures that make pleasing garden fountains for prosperous suburban manses. Considering why I’d been asked to come, I noted one glaring absence: not a single naked gay boy sculpture to be seen.

He said quite matter-of-factly, “ Take off your clothes, and have a seat on the dais.”

“Everything?” I asked, even though as I asked, I felt like a turnip just fallen off the truck.

“Everything,” he said.

And so I took off everything, which wasn’t much: sneakers, t-shirt, gym shorts, and the red Speedo which I still had on underneath.

“Lean back and relax. I’ll take photos first, then do some drawings. We’ll be about an hour – this time.”

I sat in the wooden chair and did my best imitation of relaxing, though truth be told I was a long way from relaxed. The chair was bare and a little cold against my bare flesh. I wondered how many other bare butts had sat in it – and if I could catch something just from sitting naked in a chair – a thought that came more from embarrassment than real concern. Being naked when others are clothed, even when it’s only one other, and he an artist, is unnerving for the inexperienced and naïve – both of which I was back then.

He took lots of photos, telling me what poses to assume. After a while, by which time I had relaxed a little, he had me move from the chair to a mat on the floor, and he didn’t only tell me how he wanted me to pose, he adjusted my legs and arms with his hands, to get the angle and extension he wanted for each photo. I more than half expected his hands to slide into intimate areas, and once one almost did, though it stopped just short of touching, and so it may have been accidental.

Under the circumstances, it sounds quaint to say he was “ever the gentleman, entirely professional,” though nothing happened that I could characterize otherwise. Nothing physical anyway. But I had the vivid sense that his eyes were seeing me with an intimacy and a fantasy that was the antithesis of gentlemanly and professional.

As the hour went on, I realized that I felt more naked than I’d ever felt before. And I became so utterly engrossed in nakedness that he no longer even had to tell me what poses to assume, since I became the essence of naked gay boy – which seemed to be what he wanted; and proved to be what I wanted too, though I’d had no inkling of it before I arrived at his studio. For the first time, I was naked with no hint of shame or guilt or self-consciousness, and it didn’t matter that I wasn’t alone, that he was there. Because I was naked with myself and completely at ease with it.

When the hour was up and he gave me $20 in cash, I felt almost like I shouldn’t take it; I’d had many times $20 worth of satisfaction from it all. When he asked if I’d come back again, he must have known already I’d say, “Yes.”

III

The next time, a few days later, started as the first time had: getting naked, sitting in the chair, relaxing – trying to.

“Today I’ll do drawings,” he said at the start.

The soft scratch of the pencil on the paper made relaxing easier than the clicks of the camera shutter had, before. From the chair, and then again the mat, I watched as he drew me. His eyes saw through to that nakedness that has nothing to do with clothes – that was the way I thought about the feeling I had as he looked squarely at me for minutes at a time, before looking back at his drawing pad.

After a while, I almost felt the strokes on my naked skin as I saw the pencil in his hand transfer the contours of my body onto the sheet. If I’d at all resisted the nakedness before – and the vulnerability that went with it – I quickly shed resistance that day – as quickly as I’d shed my clothes, without the need for him to tell me to again.

As he looked back and forth from my naked body to the pad, I began to wish that he’d stop drawing and look at me without looking away. Or that he’d outline my contours not with the pencil across the paper, but with his hand across my skin. He may have been fully as gentlemanly, as professional, as the time before, but I’d gone far beyond the detachment of a model on a platform – in my mind, at least. And even further in the semi-conscious other space that the long spans of static posing in the warm, still studio, and the nakedness, took me to.

He didn’t talk much as he drew. A few instructions: “Look at me,” “Tilt your head,” “Open your legs,” “Wet your lips, and part them.” I did as he directed without speaking at all. I thought of things I’d say if he gave a hint I should. But since he didn’t, I stayed silent, looking at him.

By the end of that second hour, we hadn’t exchanged a hundred words altogether, and we didn’t add to them as he put down his pencil and closed his pad, and I slipped on my shorts (no Speedo this time), and my t-shirt and sneakers. We looked at each other as he gave me the $20 for the day. He held onto it an instant longer than necessary, and I didn’t rush to pull it away.

“You’ll come back,” he said.

“Of course,” I replied. Yes, yes, of course I will, I thought, and I knew that I hoped I wouldn’t be coming back only as artist’s model, and that he was beginning to hope that too.

IV

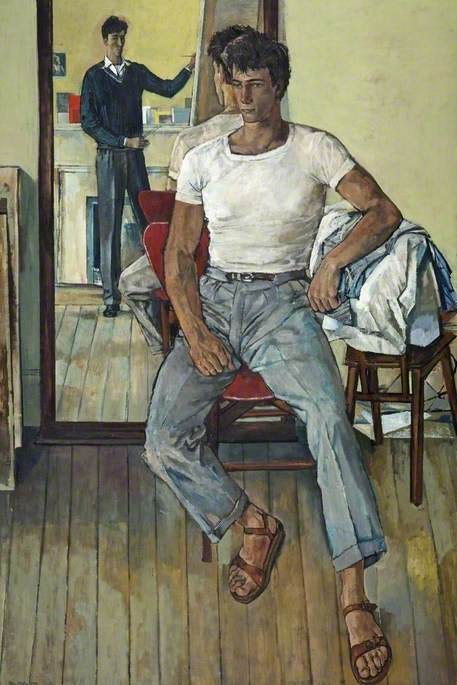

At our fourth session, when we’d grown completely comfortable with each other, and knew that there was more between us than simply artist and model, he took me back to the studio, but didn’t immediately pick up his pad and pencil. He also didn’t look away as I took off my clothes and dropped them on the floor, beside the chair on the platform. By then, I was at ease with the nakedness, and unfazed by the posing, and so I sat down in the chair, slouched back and spread my legs, let my left arm hang to the side, moved my right hand down the inside of my thigh, my thumb sliding into the crease between my leg and my groin – a pose I remembered from a John Minton painting of the artist and model in the studio – though both wore clothes in the painting. The artist, reflected in a mirror, looked at the model the same way my artist had been looking at me as he photographed and drew me: penetrating, appraising, distilling, detached.

But that wasn’t the way he looked at me today. This day would be different from those before. Instead of picking up his camera and adjusting the lens, he unbuttoned his smock, took it off, and folded it over the back of his own chair. I wet my lips and parted them as I watched.

Now I watched as he undressed – a reversal in our roles. I sat secure in nakedness while he stood, uneasy in clothes. Each garment he removed, followed by the silent penetration of my male gaze, brought us closer to the equality of shared nakedness – an equality impossible before, when one of us still hid within garments.

He didn’t shed his clothes in a rush, as I had done. He untied his bow tie, and unbuttoned his shirt slowly, button, button, button… Then, slowly, he undid his belt and slipped the button on his trousers out of it’s buttonhole. I realized he was performing a choreographed striptease – for me – a dance of the seven veils, drawn from the world of Wilde, that now, in my generation, had long since been swept away – but which, for him, still framed a world he understood – a world in which both his lives – or all his many lives, perhaps – could coexist. And I sensed that more than decades separated us. But the fascination of his performance – for me – kept me captive, gaze riveted, moistened lips parted, desire stirring – even as I knew that he’d danced the same dance before, for others – he must have done. But knowing that did not make the dance he did – for me – any less enticing.

It shocked me, near the end of his unclothing, when he stood before me in his undershirt – the sort that my generation called a tank-top – white cotton, straps over shoulders, hanging low enough to be one final veil – the kind my father had worn. My father, only recently dead, but long absent from my life in so many ways. As instantly as the realization came, I forced it away. Now was not the time for it. Maybe later.

Finally, he took off even his old-man undershirt, and stood before me in full nakedness. He stood there for a long moment as we both absorbed this shared nakedness, and the other shared aspects that clothes had masked, even clothes worn by only one of us. Now nothing was masked, and it was as though momentous things we hadn’t spoken, passed between us, still without the need of words. Then he picked up his pad and pencil, and began to draw me with a vigor that had been absent from our staid sessions before.

That day, at the end of our hour, he didn’t give me the $20. We both knew already that had never been what brought me back; now we both knew neither of us any longer needed even the pretense of it.

V

I went back many more times through the hot summer. He never again performed the striptease, not that I wouldn’t have welcomed it. But we didn’t any longer need it to get to the nakedness that really mattered, with each other. And we began to talk, as I posed and he drew or photographed. I told him about the other gay boys I met, or only lusted after – and my absent father. He told me about the men he’d known through a long life of knowing men behind all the many veils his life required – the veils he felt it required. And he told me about the wife, the children, all the constraints the social register and the deacon-ing imposed. I only half understood. I didn’t understand at all why he continued in such a life. Over beers at the bar, with my other gay-boy friends, I castigated those men who let themselves stay trapped, when they could so easily have escaped to the freedom we knew.

Toward the end of the summer, at our last session (I was going away to graduate school in a distant state), he showed me a sculpture he’d begun, had almost finished since I’d been there last – a naked faun reclining in the grass – perhaps intended for a particular suburban garden – or maybe to stay in a back corner of the studio, sometimes covered by a sheet. The faun looked somewhat like me, but maybe only because I wanted to think so.

VI

I finished my graduate work – two years in Austin – and then went back to St. Louis for a job. I hadn’t been back even to visit, never expected to be back at all, but things work out in unexpected ways. Even though I’d returned to the city, there was no reason for me to go back to the studio – he and I had left our shared summer as finished when I departed that last day – finished on amicable terms, both happy that we’d shared a summer, and shared so much through it.

There was no reason for me to go back, but I wanted to. So one hot summer afternoon, after I’d settled into my new Central West End apartment, I bicycled across Forest Park, past the lake, where the gay boys still sunned (in as little as legally possible), beside the Jewel Box (which Tennessee Williams seemed to know so well), through the wooded area to the west (where I’d peddled my assets so often in those earlier days), and past the art museum and Saint Louis, in his apotheosis reigning over his city. I peddled up Wydown, and turned into the side street where his studio was.

For old times’ sake, I wore my t-shirt and sneakers and cutoffs (no scarlet Speedo underneath), even though my new maturity and employment stature made me feel a little silly wearing them. I rang the bell and waited for him to answer.

This time it wasn’t long until the door opened – much shorter a time than usual. But it wasn’t my artist whose face I saw. It was a woman of somewhat advanced age, and though she smiled, it was a smile of form rather than animation.

I asked if my artist was there; I spoke his name.

I heard a man’s voice inside, “Yes, I’m here.” I saw him over the woman’s shoulder, coming up the hall from the studio. But it wasn’t my artist. He looked a little like him: his junior, perhaps, or maybe his 3rd or 4th. But not my artist.

When he reached the door, he said, “What can I do for you?”

For a moment I wasn’t able to speak.

“You must mean my father. He died last year. Heart attack.”

“Yes, your father. I’m sorry. I didn’t know.”

The woman stepped aside as her son came forward to take charge of the door, but I heard her ask, “How did you know my husband. Were you friends?”

Her son – their son – the woman’s and my artist’s son, stood squarely in the door, as though to block me should I try to push in, looking at me from an unsmiling face. I realized that I knew the face, that I’d seen it before, in the Potpourri or Bob Martin’s, or one of the other gay bars where I’d been a regular in my earlier Saint Louis life. Or maybe the baths. I wasn’t sure exactly, but somewhere.

“Not friends, exactly. I posed for him once. For a sculpture. I came by to say hello, and to see if he’d finished it.”

“He left so many pieces unfinished,” she said. “But I don’t remember one I’d think you had modeled for. Most are children, and dogs and cats. He loved doing those subjects most of all. He always said he loved those best.”

“Leave your name,” she said. “And if we find something like the piece you mention, we’ll let you know. Others have also come by to ask, but we haven’t been up to facing his studio till now.” Her son looked at me and said nothing.

I returned his look. I wondered if he recognized me too.

“Yes, thank you. I’d appreciate that.” And I left.

I looked up his obituary, and read about his enviable life – his deep roots in the city, going back centuries; his service in time of war; his career in art and teaching; his parents, both gone before him, his devoted wife and children, grandchildren. It was indeed an enviable life.

The obituary said nothing about the nakedness he and I had shared, of course; such things are not to be remembered, not to be spoken of, at such times. Or ever, for most. But now, fifty years later, when almost all who had to do with his story of separate lives are gone, I’m speaking of that other life, the one he and I shared through a few hours of a long-ago summer, so that it too can be remembered, even when I too am gone. It was then, and is still for many, the life that dare not speak it’s name. For him, and for his son, and for myself and all the others, I speak it now, even if only in a whisper, fifty years late.