Can’t Live/If Living Is Without Him

A St. Louis story of the 1970s

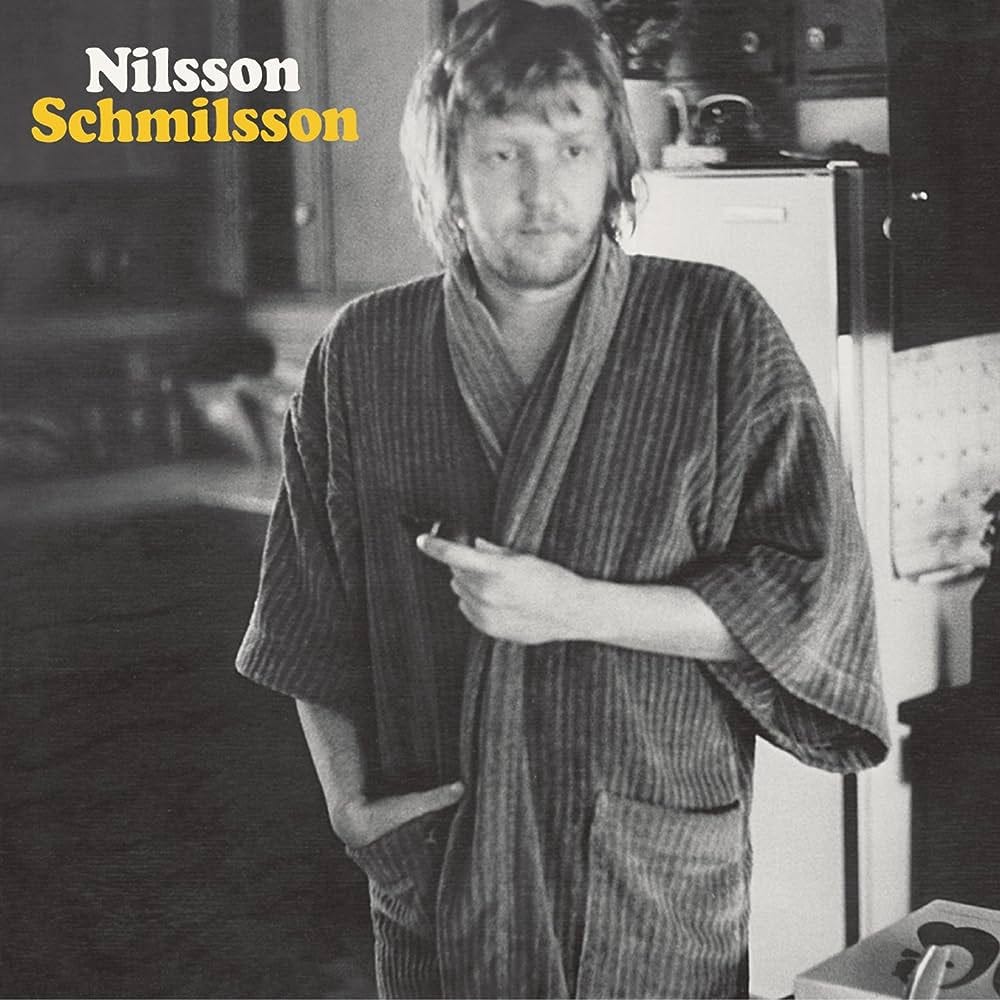

Truth is, cheap sentiment isn’t really so cheap when you’re paying for it with heartache and tears, the currency it’s usually priced in. Even now, fifty years on, when cheap sentiment is part of my program for the evening, and I pull up YouTube and click on Nilsson wailing “Can’t live/if living is without you,” I remember him and the tears flow. Not Nilsson, but that other “him” I felt in my aching heart I couldn’t live without, though living with him had become almost as painful, so it was heartache either way. Why wouldn’t there be tears?

Truth is, I did live, and so did he – though he’s dead now and I can’t be far from it. That’s what makes the tears cheap and sentimental I suppose – that neither of us did die back then from the rift and a ripped heart. If we had, it would have been a story of Mercutio and Romeo, or one as poignant, but since neither of us did, now it’s just an old man weeping for his spent youth, and all old men have that to weep for.

I remember how it ended, sitting in the front seat of his car, on West Pine, one night a couple of years after it began – after some drinks and some smokes – and some vituperation. I think I was the one who asked, “So it’s over?” not really believing it could be – because even then I heard Nilsson in the back of my mind. His answer, “I guess it is,” stunned. We both sat silent for a while, not crying, not looking at each other – looking straight ahead through the windshield at dark nothing.

After a while I opened the passenger door and got out. I didn’t slam the door, just shut it. He started the engine and drove off, and it was over, just like that. Still standing in the dark on the sidewalk in front of the Hawthorn, my apartment building, still stunned, then I cried, and Nilsson got louder, so loud I was afraid he’d wake the neighbors.

Funny, since I remember so clearly how it ended, that I don’t remember at all how it began. It must have been in a gay bar, since that’s where I spent most of my free time then. In Saint Louis. In the Potpourri or Bob Martin’s, or some other one whose name eludes me now. Some first nights and lots of one-night-stands I do recall, but that first night, with him, not at all. There were many more nights with him over the next two years, blended into one vivid memory of passion – the passion of 25, which, at 75 hardly seems creditable – would seem unbelievable if the memories (and the tears) weren’t witnesses vouching for it.

I know it included sex, and smokes and drinks, and poppers, likely, since most all the nights did then. We’d have seen each other across the bar or dance floor, or been introduced by some mutual friend/acquaintance/former trick. I’d have been attracted by his dimpled smile and his ginger beard, his muscled chest and slim hips, never mind his bulge, which then I could only hope would fulfill the promise it made in his button-fly jeans.

It would be prurient of me to say whether or not the promise was fulfilled, and the only thing worse than cheap sentiment for old men to indulge is gratuitous remembered sex. We’ve all had it – sex – or haven’t in a long, long time, but either way it goes limp on the page for the high minded who are looking for something profound.

All went along smoothly at first, with the ups and downs of hangovers, and respective hang-ups, and, after a while, occasional infidelities. Fidelity wasn’t supposed to be a gay thing then, but some of us still clung to the idea of it, even if we didn’t always manage the reality, with or without “an understanding.” For most of us – for me and him, for sure – the understandings were mostly situational: sometimes we both understood, and sometimes only one of us did, and sometimes neither.

It's hard to see now how things really were, through the fog of addiction (however long 12-stepped), and the mist of sentiment, and the gauze of fifty years. It could be that we were building on sand from the beginning, though it never seems that way at the start – or we never want to believe it. I have no doubt we were both good men at heart, both looking for more than sex, or at least more to go along with sex. Because then, sex went along with everything one way or another. You didn’t have Saturday breakfast at the Majestic or Sunday mass at the Cathedral, workaday drudgery or holiday trips home to see the folks without sex having some part in it. It’s just the way it was at 25 in the gay ghetto in the gay 1970s. We didn’t fight it, but then why would we. Could anything have been better then the gay sex of the 70s, coming as it did in the blink between centuries of faggots in flames and the death knell of AIDS? It was paradise old fairies had dreamed of all their lives, everyone young going down the long slide to happiness, endlessly (pardon the mangled plagiarism).

Except that it wasn’t all happiness, and it did end. The death knell did sound. For me and him not as it did for the millions who found that indeed they couldn’t live, no matter how desperately they wanted to. But that was later, and was real tragedy – broken lives, not the melodrama of broken hearts. And yet even melodrama hurts, all the more without the wisdom of age, and with the unrelenting hormones and the tormenting traumas of youth. How minor those seem on balance, how trivial in the long-term, and yet the heartache and the pain still hurt. They hurt me as I watched him drive away.

The same hurt I felt when he invited another man into our bed. Or rather invited me into the bed they’d been sharing at the Dauphin Island beach house before I got there. He honestly seemed to think I’d be pleased by the taut young flesh he offered like a tomcat after a night out, proudly presenting his mouse prize, still warm, clutched in his jaws. It was the first, but not the last – far from the last – of our misunderstandings.

I made it clear I wasn’t having it, and he came to bed with me alone. He truly didn’t seem to understand, but there were no more mouse offerings, and we made it another year, until that last night in the front seat of the parked car on West Pine, and the end.

He came to Chicago to be with me on weekends when I went there temporarily for work, or I went back to Saint Louis to be with him. Of course there was the wonder and the worry about the days and nights between, but by then our understanding went at least as far as silence – don’t ask, don’t tell twenty years early.

Maybe it shouldn’t have mattered. It’s not as though there was any less sex for us because there was more of it than the sex we shared together – or wouldn’t have been any less if sex and power and control hadn’t got all tied together with a Gordian bow.

Glitter-and-be-gay Lucy – older, wiser – counseled me with her example as she mused on loneliness and the compromises she’d now be willing to make – too late – if she’d known how lonely it would be once she threw her philandering husband out. She’d shared her wisdom many times with many a tearful gay boy, so tears no longer glistened in her own eyes as she shared it. Though who could know for sure about those cheap sentimental times when she wasn’t glittering, was alone. I was too young and too love-besotted to see how any of it had anything to do with me. My love, with him, was – in the way of youth – unlike any other. There never had been, never would be, another love like it. That’s why it was a love worth dying from.

In the early days, after one of the early nights, I waxed poetic, with a poem that seemed prophetic after the end:

I remember his dark eyes, How they looked looking at me in the night. Dark lights lit in his shadowed face, They drew me closer than lovers' arms. When his dark eyes looked at me in the night, They spoke of love, and I believed them. His lover's arms drew me close, And his lover's lips drank me in. His whole body spoke of love, and I believed him. I was a better prophet than I was a poet. There was no looking at each other that last night.

A few months proved that in fact I could live without him – would have to if I were going to keep living at all. And, of course, after a few months the thought that I might not keep living seemed ludicrous. Of course I would. No one ever actually dies from heartache, and it’s only drama to say you wish you would. Or melodrama, given that we’re adrift on the sea of tears and cheap sentiment. But even so, it still hurt – in an aching way that’s never salved by knowing it’s not fatal.

I saw him a few times afterwards, out at the gay bars with other men – or on the hunt for them – or on the neighborhood streets, tending to the business of life. At first, by unspoken mutual understanding, we didn’t see each other; and then after a while longer we nodded and walked on. Once, we smiled and said, “How are you?” – though neither of us really wanted to hear the answer. For sure, I didn’t.

In a few years we both moved on to other cities, other lovers. Forty years flew by. The world changed and our lives changed, and only memory of something long ago and “in another country,” something aching that still brought tears, remained to prove there’d ever been such a thing as “us.”

By the time I Googled him, when I’d reached the sentimental, looking-back phase, his obituary led the list of hits. It gave the facts of husband, adopted sons, 40 years of life, then death. Seeing that was hard enough.

But then Facebook provided photos – even video: a last birthday party just days before the end, husband, sons, sister, dog, trying to hide their sorrow behind a cake and song. Not the robust, virile, gorgeous, even funny man whose memory I’d cherished all those years. An old man, ill and shriveled, his face uncomprehending – of the party, celebrating one last time his too-short life? – even less, of what lay ahead so soon? Or was it my own incomprehension I was seeing. How could this be him, even after 40 years? It was beyond my understanding, never mind that I’d grown old myself, and must also be sliding toward my end. But I’d watched that happing day-by-day, not shuddered from the jolt of 40 years flashing by instantly.

Seeing those photos – oh, the tears flowed then. I felt like an intruder, barging into their lives, into their time of aching sorrow – but I couldn’t look away. It was part of my life too, my sorrow, though even he, the only one who might have known why I had claims to join them, was beyond validating my right by then.

The trouble with cheap sentiment is knowing when to stop it, and how. But really no reason to worry, I suppose, since nature has a way of making sure it doesn’t go on too long. Shakespeare’s seven ages come to mind, though by now they’ve dwindled almost to none. There’s no more “sighing like furnace” – the sentimental tears have cooled those flames. Still clinging to the “shrunk shank” and “childish treble” for a little while, awaiting the “sans everything” which will come so soon.

Another look at the photos. Nilsson still wailing in the background, though soon for someone else. Beyond comprehension. And then it’s over, just like that.