An Old Man and His Memories - Pt 2: I Caught Him Reading

Looking Back at a Long Queer Life

(Note: And so we continue An Old Man and His Memories, the final section of our historical trilogy. Our Narrator, whose memories stretch back to a youth of love and discovery in Paris, told in Song of the Amorous Frogs; and then a middle-age of art and discovery in Houston, continued in Left Bank on the Bayou; has now grown old, and lives his days, as he has for 30 years, in an apartment in the Hawthorne, in St. Louis, and in his memories: an apartment that had once been theirs, now his alone, and memories that had once been theirs – his and so many others in his life – now also his alone, because only he is still alive to remember them.)

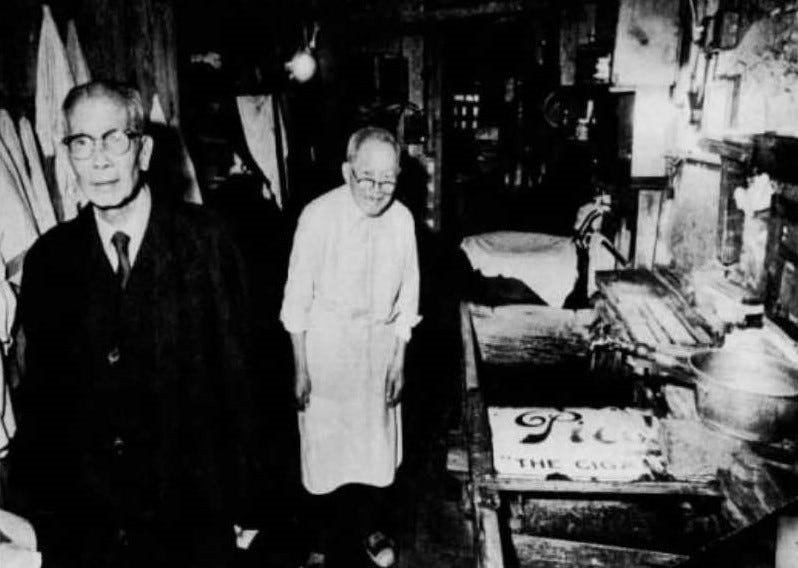

As I stood at the counter of Sam Wah – among the last remaining of the once plentiful Chinese hand laundries that had dominated the laundry business in St. Louis – my eyes followed the green tendrils that meandered around the ceiling and windows. We called it an “ivy” when we mentioned it in amazement, though likely it wasn’t botanically an ivy at all, but something else that could thrive, or at least survive, on years – maybe decades – of inattention and little water, verging almost on abuse. Much as Sam Wah, and the other St. Louis Chinese had survived over the decades, perhaps.

There was a move afoot to save Sam Wah from destruction as the ever-expanding institutional behemoth of the neighborhood, the Washington U Medical Center, hulked its way further east. I supported the effort to save it: I could not imagine entrusting my shirts to anyone else, after so long; but I left the protesting and petitioning to others. As I grew older, and my time grew shorter, I left more and more to others. An old man does not have time, or energy, for all things, even all good things – must choose the few most important things (important for him, at least) to give himself to. Even though knowing for sure which are “most important” might often be difficult.

My eyes followed the vine back to its encrusted pot on the window ledge as I waited. In a few moments, one of the Gee brothers, who now operated the laundry – they alternated between manning the counter and supervising operations further back (laundering, ironing, folding, bundling) – handed me my parcel of shirts, tied in brown paper with twine. I paid – cash, no check/no charge. We nodded, as we had done a thousand times before.

As I walked back out onto the sunny street, I wondered if the vine might prove to be the lucky mole hair for the longevity of Sam Wah. I hoped so. I’d seen quite enough of change to make me right and truly sick of it, when it came to the foundation elements of my world.

I walked west on Laclede, the two blocks to Euclid, and went into the not quite greasy spoon on the corner, Habs House. I greeted the owner at the counter, and nodded to his wife at the grill, doing the short-order cooking. We knew each other for pleasantries, but not by names.

I bought a coffee, not so much because I wanted coffee, but as a reason for being there, to see if the young man I’d seen there so often before was there again. And he was, sitting at his usual table by the window on Euclid, the remnants of his two-eggs-up-with-toast pushed aside, his own paper cup of coffee before him, his eyes seeing only the pages of the paperback book he read. Faulkner today, as it had been for a while now. Before that, Dostoevsky. I’d even watched him reading Proust at times (the Scott-Moncrieff translation), scribbling words on a pad – perhaps the many that would be unfamiliar to a young reader, to be looked up later – as I had done myself once upon a remembered time, long ago.

I thought of him as “boy,” that nostalgic term for young men so much younger than an old man like me, though he must certainly have been well into his 20s. I’d never spoken to him, though once or twice we’d smiled. I suspected him of being an aspiring writer, as I had been myself – long ago. So long ago that it seemed as though I must be remembering some other person. Could that really have been me?

I looked at him, not with an old-man’s lascivious eye – though I can’t deny at least a tatter of desire (so not quite dead yet) – but perhaps with a little envy that he still had so much ahead of him that I now could only dimly see in my past. It would not all be easy or pleasant, likely much would be painful, but all part of a life yet to be lived, instead of one now mostly to be remembered.

This was not to be another day of smiles exchanged for us. Faulkner proved too absorbing a rival. And so after I’d watched him read for a while – discretely enough, I hoped, so as not to be found out by our Habs House hosts – I got up to leave, getting almost to the door before I realized I’d left my parcel of shirts on the table. As I went back to get it, I blushed a pink only a little paler than the petals falling from the spring trees outside. I glanced at him and at the owners. If he glanced back, I missed it.

I glanced at him again, through the window, as I walked up Euclid. This time he did glance back, though his glance may have missed seeing me as it focused on distant Yoknapatawpha instead. I understood. I soon glanced myself into the distance, to the past. And so we became fellow travelers to other times and other places, joined in a flight from this world that we shared, into others that we didn’t.

When I’d first joined Clem and Our Cellist in their two-bedroom Hawthorne apartment, I’d had my bedroom and they theirs. After I’d been there for a while (but not too long a while) both bedrooms became “ours.” None of us ever said the words to make it so, but we all came to know, accept, even relish that it was so. Even though I had come into their space, I never felt, nor was made to feel, an interloper. I’d come late to the apartment, but I’d been first in knowing each of them, which soon seemed to make us all equals in our menage – sooner and more smoothly than I might have either hoped or dreamed – if I’d been able even to imagine (dream of) such a menage for us at all before it happened. What I’d first thought might be displeasure from Our Cellist at the arrangement, soon enough became acceptance, may only have been Gallic reserve all along. And Clem, straightforward as always, made his druthers clear early on. After just a little time, I simply shook my head in wonder whenever I thought back about it. Our new connection quickly came to seem the inevitable outcome of all that had led us to it. Always meant to be. Why even question how it came to be. Even our tiny table at Café Gaudeamus in far away Paris would now be large enough for three.

In those days, those early winter days of 1943, we took the first faltering steps toward a life that would see us comfortingly through the next many years. Clem had found a new freedom in St. Louis after so long constrained, in Chicago, and even in far away Paris, by the expectations that came along with “close-knit” family – which is to say, a father, and even a mother and milieu, with expectations of the man he should be, no matter the man he was.

Neither Our Cellist nor I had those external expectations to conquer – his family far away in some rural French village that he had not visited in decades, mine all gone. He seemed to have found all he needed with his symphony chair and musical life in this outpost of France, where Saint-Louis himself reigned atop the highest hill in Forest Park. All of us sensed the rightness of our coming together at last after so long of being only partly the whole we now seemed meant to be.

As I continued up Euclid to West Pine, and turned to take my shirts back to my Hawthorne apartment – now “mine” alone, since I now alone remained to live in it – I thought back over those many years when the apartment had been “ours,” and how we’d enlarged our domestic domain over the decades, as adjacent apartments – first the efficiency next door, and then the one next to that – came empty, and we’d moved into them as well. At last we’d had almost the whole 17th floor, each of us with a door that closed, for when any needed a room of his own, but all having all the keys.

They had not been perfect times, because no times ever are. But they had been “our” times, in a way none of us could have imagined before they came, and which now I missed more deeply than I could ever have imagined. Now that they were gone (the times AND the men), I so often feared I hardly had the courage to endure.