An Old Man and His Memories - Pt 1: In the Lobby of the Hawthorne

Looking Back at a Long Queer Life

(Note: And so we begin An Old Man and His Memories, the final section of our historical trilogy. Our Narrator, whose memories stretch back to a youth of love and discovery in Paris, told in Song of the Amorous Frogs; and then a middle-age of art and discovery in Houston, continued in Left Bank on the Bayou; has now grown old, and lives his days, as he has for 30 years, in an apartment in the Hawthorne, in St. Louis, and in his memories: an apartment that had once been theirs, now his alone, and memories that had once been theirs – his and so many others in his life – now also his alone, because only he is still alive to remember them.)

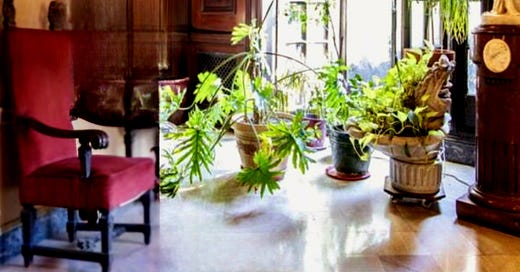

I sat in one of the big chairs at the far end of the lobby of the Hawthorne Apartments, my home for almost 30 years now, in the Central West End of St. Louis. Not a comfortable chair – straight back, sturdy seat, ornate carved wood arms – but comfortable enough for me to doze from time-to-time as I sat, taking in the mundane comings and goings through the lobby and the revolving brass door.

The April breezes gently lifted the long white sheers at the open French windows into the room, dusty banners of virginity in this bastion of mostly spinster females of a certain age and class. Clem and Our Cellist and I had been among the few males in residence, but males of no threat to the dusty virginity of our lady neighbors.

Outside the windows, flowering plums bloomed in all their pink glory, the petals dancing and swirling on the breezes, and then settling to the ground as pink carpets. Just as I remembered them all those years ago in the Square Paul Langevin (as now called; then, Square Monge) in Paris, as I did vigil across from the hotel I’d been summoned to by Clem, after his long abandonment, when he’d gone back to his “normal” life of family and career in Chicago. That day 50 years before, I’d sat so long, watching as Clem (or someone; it could have been him) opened the balcony window of a room (it could have been his room) to let in the sweet spring air, and, perhaps, to glance out wondering if I would come. I’d sat there so long that the pink petals covered my shoulders and trouser legs along with the bench and path. I’d sat wondering if I would, or could, summon the strength to go in to greet him and pass pleasantries and reminiscences about “wild and foolish” days now past, days before Clem had gone away, before I’d first heard My Cellist play, before I’d cried all the lonely tears that flooded me forward into the life without him.

That day, I had wiped away the tears (after a while); and stood and brushed away the petals; and I had not gone in. This day, as I watched a few of the petals drift in around the sheers, I felt a tear again, at remembrance of things past, and I did not wipe it away until it had gone halfway down my cheek. Old men may cry fewer tears than youths, I thought, but they can be as warm.

That day, I had stood and walked out of the Square, into the rue des Écoles, away from Clem, as he had gone away from me the day I saw him off at Gare d’Austerlitz, leaving me downcast that I was to be alone in Paris for days, perhaps weeks, until he returned from Toulouse and the meeting with his father. His letter, when it arrived, telling me he would not return, left me overcome with sorrow.

This day, I stood and walked across the Hawthorne lobby, greeting the doorman, Jimmy, as I reached the door, then going out into the gorgeous day, a West Pine flâneur suddenly overcome by a feeling of bliss, even though over 70, even though strolling only to the Sam Wah Chinese Laundry on Laclede to fetch my shirts which they had been washing, ironing, folding for me (and so many others) for so many decades.

Ahead I saw two boys walking up the street holding hands. It continually amazed (and exhilarated) me how bold and open the young gays were these days. As though they had no fears or shame about their queerness. We’d had our places of openness, of course – every queer generation has, going all the way back to the climb out of the sea. But seldom, or maybe never before, openly on the street, in the full daylight. Thrilling proof that sometimes there is something new under the sun.

Seeing them brought to mind lines I’d read recently, by the English poet, Philip Larkin – not bad, though no Tom Elliot, certainly, our St. Louis boy who chose England so long ago:

“… I know this is paradise

Everyone old has dreamed of all their lives –

… everyone young going down the long slide

To happiness, endlessly …”

The desire each of these boys had for the other, physical desire, not only the more chastely laudable spiritual kind, trailed behind them like a comet’s tail. I picked up my pace a bit – not too much, at my age, but a bit – so that the dust from it might settle on me before it drifted away in the air. It was that desire I missed most now that I’d become the old man remembering the young man and his desire-bathed life then – that other person and life I used to inhabit in youth – the desired and the desiring in one. Though in some ways the absence of desire made life easier to live.

My feet knew the way to the laundry so well that my mind could stay completely in that day, 50 years in the past, when I walked away from Clem forever – so I thought: what improbable twists life brings!

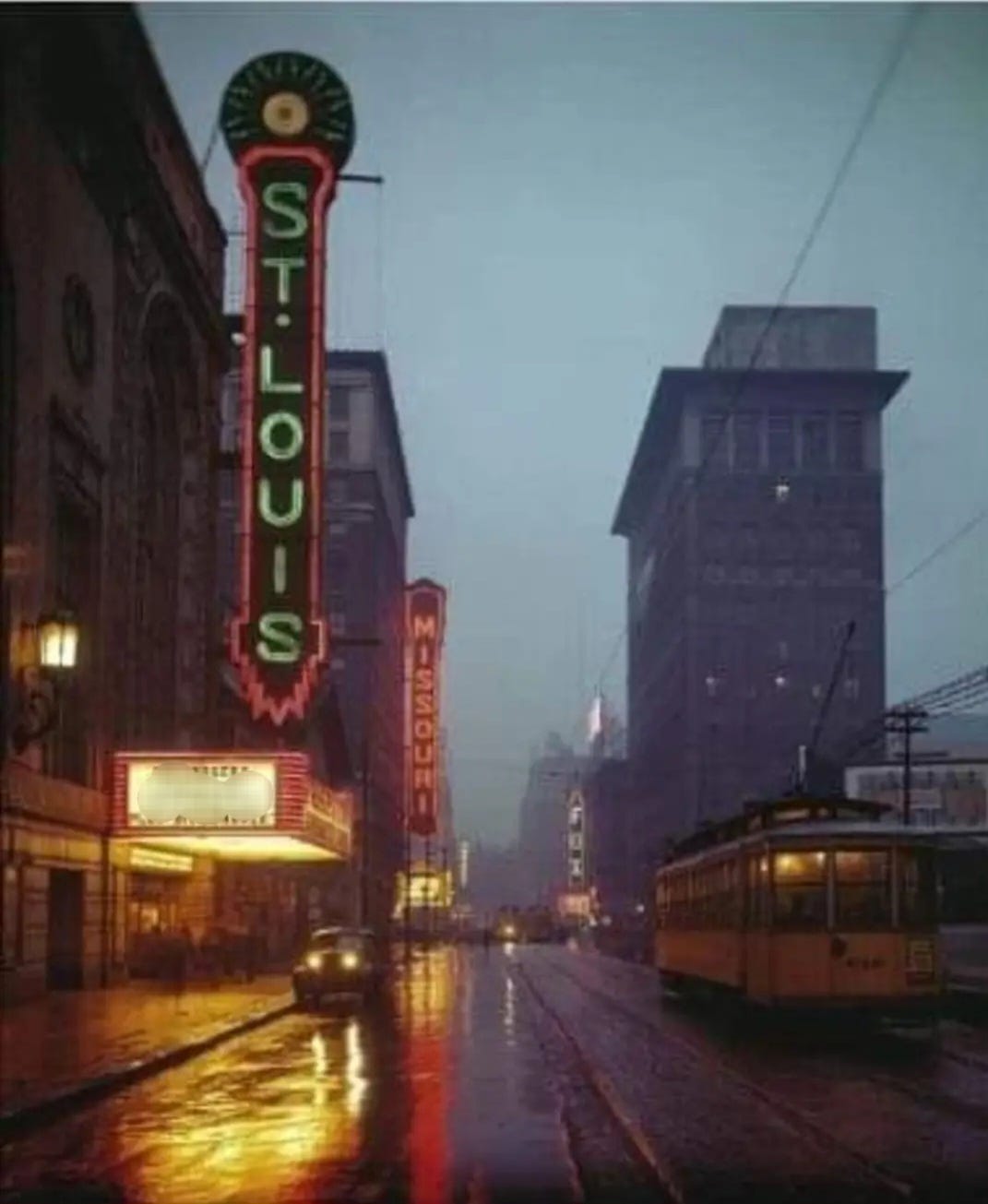

I’d come back to St. Louis in the cold early months of 1943, at Clem’s invitation, thrown in at the end of a letter about other things, perhaps with no thought that I might actually accept. But I did. The War had hollowed out my Houston circle, and thus my Houston life – Russell gone, Lorin gone, Gene, Cardy, Forrest, and at last even Margo, gone – so why should I stay, the last of our outré tribe remaining? Yes, Houston was a city of the future, St. Louis one of the past, but not many were farsighted enough (not I, certainly) to see that then. And what difference did past city or future city make to one floundering (I, certainly) in an uncertain present? Not that certainty, past, present or future, is ever more than an illusion. Still, even the illusion of it had flown away for me by then, and so I opted for the geographic cure, and flew away myself, to St. Louis. Or rather, took the train, since few flew then.

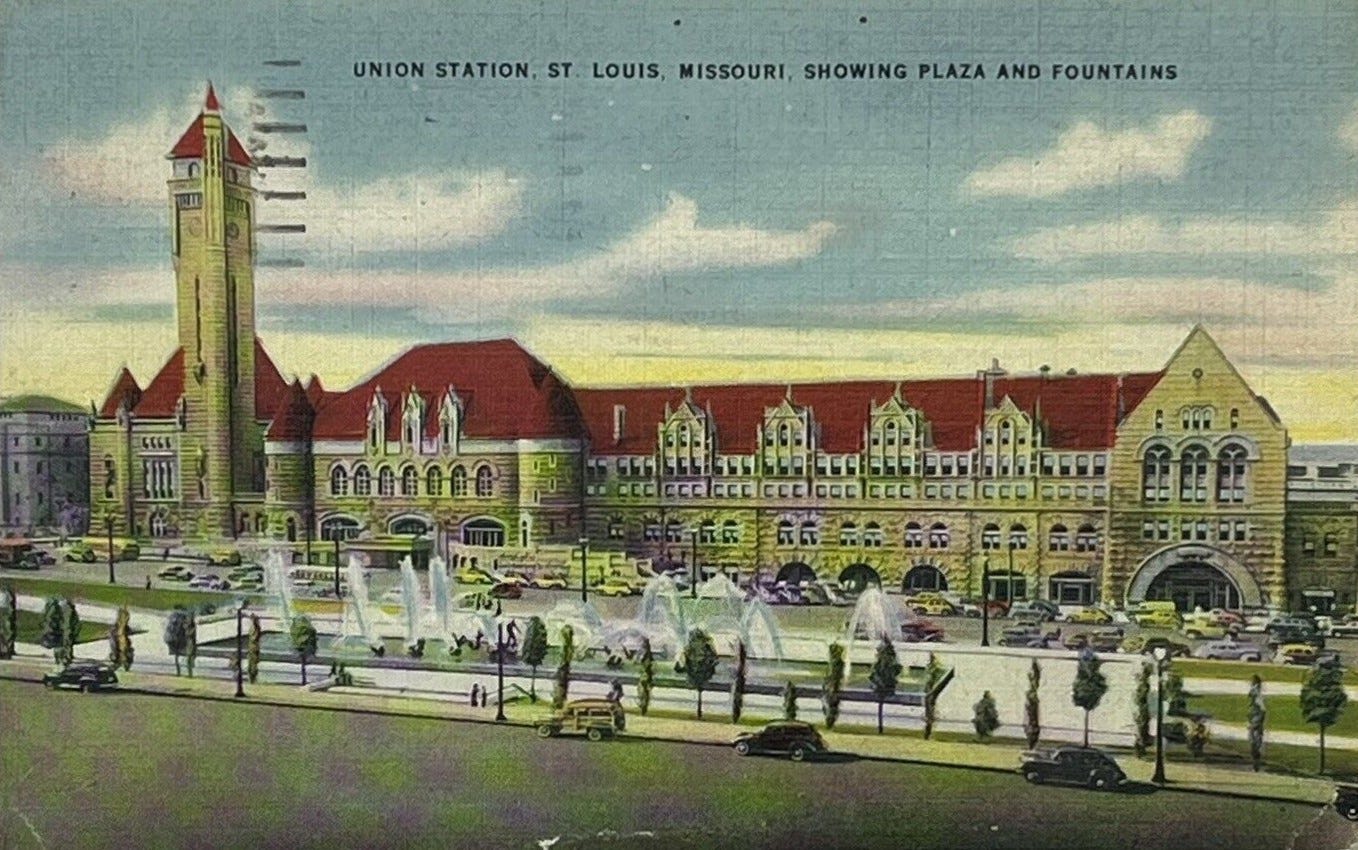

After so many years of mild winters on the Gulf, a sudden re-immersion in the blast-of-cold winter wallop in even barely northern St. Louis, sobered me out of illusions of a paradise in my new old city. I had forgotten how cold the place could be when someone (God?) left the door to the Arctic ajar, with only prairies between the two points, of no use in breaking the frigid winds. Even though Clem’s hearty greeting when I stepped off the train made the air seem almost warm (that of Our Cellist, not so much), the cold of the train shed tempted me to go directly to the window for a ticket south.

I did not, could not as Clem (Our Cellist, not so much) rushed me and my luggage into a taxi and told the driver to take us to The Hawthorne, as though everyone knew The Hawthorne, of course. This driver, if not everyone, did know. And almost before we’d had time to wonder to each other at the fact of my being there, and wonder each silently what the future would hold for the three of us together, we got out on West Pine, stood for a moment in the cold before the grand revolving door as Clem paid the driver, and then each of us took a suitcase and stepped lively up the five steps and into the warm lobby and greeted the smiling Jimmy, as I had done again today, and for 30 years – the Jimmy then so young; now, like me, so growing old. The first day of the rest of my life, as the young were now so fond of saying.

This warm pink lovely day I watched the boys as they turned left at Newstead, going, perhaps, for a look at the glorious mosaics inside the magnificent Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis, on Lindell. Or (and this, perhaps, as much an old man’s dream as a reality) to a small apartment somewhere near, large enough no matter how small for their desires to flower as beautifully as the spring trees.

I turned right, the direction of Sam Wah, but I glanced back over my shoulder at the boys, just as I glanced back over the years at the boys we had been, Clem, Our Cellist, I – and many others – in the days of our own small apartments filled with our own flowering desires. And even the memories of disappointments so often coupled with the desires could not blunt my bliss (tinged with melancholy as it might be) on a day as beautiful as this. How fine, I thought, to be walking, in my golden age, on pink carpets through air scented with desire, even though someone else’s. A paradise the old – AND young – have dreamed of all our lives.

Love these lines - “The desire each of these boys had for the other, physical desire, not only the more chastely laudable spiritual kind, trailed behind them like a comet’s tail. I picked up my pace a bit – not too much, at my age, but a bit – so that the dust from it might settle on me before it drifted away in the air.”

Loved this story, so sweet, so memory-laden, reflecting the exquisite beauty and the sad regrets of life. It warmed me on this cold day.